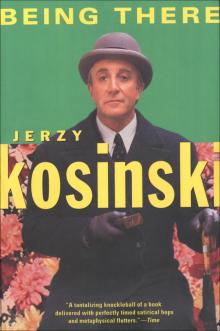

Being There

Jerzy Kosiński

Being There

BOOKS BY JERZY KOSINSKI

NOVELS

The Painted Bird

Steps

Being There

The Devil Tree

Cockpit

Blind Date

Passion Play

Pinball

The Hermit of 69th Street

ESSAYS

Passing By

Notes of the Author

The Art of the Self

NONFICTION

(Under the pen name Joseph Novak)

The Future Is Ours, Comrade

No Third Path

Being There

Jerzy Kosinski

Copyright © 1970 by Jerzy Kosinski

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kosinski, Jerzy N., 1933-1991

Being there / Jerzy Kosinski.

p. cm.

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9581-4

I. Title.

PS3561.08B45 1999

813’.54—dc21 99-10245

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

For Katherina v. F.

who taught me that love

is more than the longing to be together

This is entirely a work of fiction, and its characters and events are wholly fictional. Any similarity to past or present characters or events is purely accidental, and no identification with any character or event is intended.

THE AUTHOR

One

It was Sunday. Chance was in the garden. He moved slowly, dragging the green hose from one path to the next, carefully watching the flow of the water. Very gently he let the stream touch every plant, every flower, every branch of the garden. Plants were like people; they needed care to live, to survive their diseases, and to die peacefully.

Yet plants were different from people. No plant is able to think about itself or able to know itself; there is no mirror in which the plant can recognize its face; no plant can do anything intentionally: it cannot help growing, and its growth has no meaning, since a plant cannot reason or dream.

It was safe and secure in the garden, which was separated from the street by a high, red brick wall covered with ivy, and not even the sounds of the passing cars disturbed the peace. Chance ignored the streets. Though he had never stepped outside the house and its garden, he was not curious about life on the other side of the wall.

The front part of the house where the Old Man lived might just as well have been another part of the wall or the street. He could not tell if anything in it was alive or not. In the rear of the ground floor facing the garden, the maid lived. Across the hall Chance had his room and his bathroom and his corridor leading to the garden.

What was particularly nice about the garden was that, at any moment, standing in the narrow paths or amidst the bushes and trees, Chance could start to wander, never knowing whether he was going forward or backward, unsure whether he was ahead of or behind his previous steps. All that mattered was moving in his own time, like the growing plants.

Once in a while Chance would turn off the water and sit on the grass and think. The wind, mindless of direction, intermittently swayed the bushes and trees. The city’s dust settled evenly, darkening the flowers, which waited patiently to be rinsed by the rain and dried by the sunshine. And yet, with all its life, even at the peak of its bloom, the garden was its own graveyard. Under every tree and bush lay rotten trunks and disintegrated and decomposing roots. It was hard to know which was more important: the garden’s surface or the graveyard from which it grew and into which it was constantly lapsing. For example, there were some hedges at the wall which grew in complete disregard of the other plants; they grew faster, dwarfing the smaller flowers, and spreading onto the territory of weaker bushes.

Chance went inside and turned on the TV. The set created its own light, its own color, its own time. It did not follow the law of gravity that forever bent all plants downward. Everything on TV was tangled and mixed and yet smoothed out: night and day, big and small, tough and brittle, soft and rough, hot and cold, far and near. In this colored world of television, gardening was the white cane of a blind man.

By changing the channel he could change himself. He could go through phases, as garden plants went through phases, but he could change as rapidly as he wished by twisting the dial backward and forward. In some cases he could spread out into the screen without stopping, just as on TV people spread out into the screen. By turning the dial, Chance could bring others inside his eyelids. Thus he came to believe that it was he, Chance, and no one else, who made himself be.

The figure on the TV screen looked like his own reflection in a mirror. Though Chance could not read or write, he resembled the man on TV more than he differed from him. For example, their voices were alike.

He sank into the screen. Like sunlight and fresh air and mild rain, the world from outside the garden entered Chance, and Chance, like a TV image, floated into the world, buoyed up by a force he did not see and could not name.

He suddenly heard the creak of a window opening above his head and the voice of the fat maid calling. Reluctantly he got up, carefully turned off the TV, and stepped outside. The fat maid was leaning out of the upstairs window flapping her arms. He did not like her. She had come some time after black Louise had gotten sick and returned to Jamaica. She was fat. She was from abroad and spoke with a strange accent. She admitted that she did not understand the talk on the TV, which she watched in her room. As a rule he listened to her rapid speech only when she was bringing him food and telling him what the Old Man had eaten and what she thought he had said. Now she wanted him to come up quickly.

Chance began walking the three flights upstairs. He did not trust the elevator since the time black Louise had been trapped in it for hours. He walked down the long corridor until he reached the front of the house.

The last time he had seen this part of the house some of the trees in the garden, now tall and lofty, had been quite small and insignificant. There was no TV then. Catching sight of his reflection in the large hall mirror, Chance saw the image of himself as a small boy and then the image of the Old Man sitting in a huge chair. His hair was gray, his hands wrinkled and shriveled. The Old Man breathed heavily and had to pause frequently between words.

Chance walked through the rooms, which seemed empty; the heavily curtained windows barely admitted the daylight. Slowly he looked at the large pieces of furniture shrouded in old linen covers, and at the veiled mirrors. The words that the Old Man had spoken to him the first time had wormed their way into his memory like firm roots. Chance was an orphan, and it was the Old Man himself who had sheltered him in the house ever since Chance was a child. Chance’s mother had died when he was born. No one, not even the Old Man, would tell him who his father was. While some could learn to read and write, Chance would never be able to manage this. Nor would he ever be able to under

stand much of what others were saying to him or around him. Chance was to work in the garden, where he would care for plants and grasses and trees which grew there peacefully. He would be as one of them: quiet, openhearted in the sunshine and heavy when it rained. His name was Chance because he had been born by chance. He had no family. Although his mother had been very pretty, her mind had been as damaged as his: the soft soil of his brain, the ground from which all his thoughts shot up, had been ruined forever. Therefore, he could not look for a place in the life led by people outside the house or the garden gate. Chance must limit his life to his quarters and to the garden; he must not enter other parts of the household or walk out into the street. His food would always be brought to his room by Louise, who would be the only person to see Chance and talk to him. No one else was allowed to enter Chance’s room. Only the Old Man himself might walk and sit in the garden. Chance would do exactly what he was told or else he would be sent to a special home for the insane where, the Old Man said, he would be locked in a cell and forgotten.

Chance did what he was told. So did black Louise.

As Chance gripped the handle of the heavy door, he heard the screeching voice of the maid. He entered and saw a room twice the height of all the others. Its walls were lined with built-in shelves, filled with books. On the large table flat leather folders were spread around.

The maid was shouting into the phone. She turned and, seeing him, pointed to the bed. Chance approached. The Old Man was propped against the stiff pillows and seemed poised intently, as if he were listening to a trickling whisper in the gutter. His shoulders sloped down at sharp angles, and his head, like a heavy fruit on a twig, hung down to one side. Chance stared into the Old Man’s face. It was white, the upper jaw overlapped the lower lip of his mouth, and only one eye remained open, like the eye of a dead bird that sometimes lay in the garden. The maid put down the receiver, saying that she had just called the doctor, and he would come right away.

Chance gazed once more at the Old Man, mumbled good-bye, and walked out. He entered his room and turned on the TV.

Two

Later in the day, watching TV, Chance heard the sounds of a struggle coming from the upper floors of the house. He left his room and, hidden behind the large sculpture in the front hall, watched the men carry out the Old Man’s body. With the Old Man gone, someone would have to decide what was going to happen to the house, to the new maid, and to himself. On TV, after people died, all kinds of changes took place—changes brought about by relatives, bank officials, lawyers, and businessmen.

But the day passed and no one came. Chance ate a simple dinner, watched a TV show and went to sleep.

He rose early as always, found the breakfast that had been left at his door by the maid, ate it, and went into the garden.

He checked the soil under the plants, inspected the flowers, snipped away dead leaves, and pruned the bushes. Everything was in order. It had rained during the night, and many fresh buds had emerged. He sat down and dozed in the sun.

As long as one didn’t look at people, they did not exist. They began to exist, as on TV, when one turned one’s eyes on them. Only then could they stay in one’s mind before being erased by new images. The same was true of him. By looking at him, others could make him be clear, could open him up and unfold him; not to be seen was to blur and to fade out. Perhaps he was missing a lot by simply watching others on TV and not being watched by them. He was glad that now, after the Old Man had died, he was going to be seen by people he had never been seen by before.

When he heard the phone ring in his room, he rushed inside. A man’s voice asked him to come to the study.

Chance quickly changed from working clothes into one of his best suits, carefully trimmed and combed his hair, put on a pair of large sunglasses, which he wore when working in the garden, and went upstairs. In the narrow, dim book-lined room, a man and a woman were looking at him. Both sat behind the large desk, where various papers were spread out before them. Chance remained in the center of the room, not knowing what to do. The man got up and took a few steps toward him, his hand outstretched.

“I am Thomas Franklin, of Hancock, Adams and Colby. We are the lawyers handling this estate. And this,” he said, turning to the woman, “is my assistant, Miss Hayes.” Chance shook the man’s hand and looked at the woman. She smiled.

“The maid told me that a man has been living in the house, and works as the gardener.” Franklin inclined his head toward Chance. “However, we have no record of a man—any man—either being employed by the deceased or residing in his house during any of the last forty years. May I ask you how many days you have been here?”

Chance was surprised that in so many papers spread on the desk his name was nowhere mentioned; it occurred to him that perhaps the garden was not mentioned there either. He hesitated. “I have lived in this house for as long as I can remember, ever since I was little, a long time before the Old Man broke his hip and began staying in bed most of the time. I was here before there were big bushes and before there were automatic sprinklers in the garden. Before television.”

“You what?” Franklin asked. “You lived here—in this house—since you were a child? May I ask you what your name is?”

Chance was uneasy. He knew that a man’s name had an important connection with his life. That was why people on TV always had two names—their own, outside of TV, and the one they adopted each time they performed. “My name is Chance,” he said.

“Mr. Chance?” the lawyer asked.

Chance nodded.

“Let’s look through our records,” Mr. Franklin said. He picked up some of the papers heaped in front of him. “I have a complete record here of all those who were at any time employed by the deceased and by his estate. Although he was supposed to have a will, we were unable to find it. Indeed, the deceased left very few personal documents behind. However, we do have a list of all his employees,” he emphasized, looking down at a document he held in his hand.

Chance waited.

“Please sit down, Mr. Chance,” said the woman. Chance pulled a chair toward the desk and sat down.

Mr. Franklin rested his head in his hand, “I am very puzzled, Mr. Chance,” he said, without lifting his eyes from the paper he was studying, “but your name does not appear anywhere in our records. No one by the name of Chance has ever been connected with the deceased. Are you certain, Mr. Chance—truly certain—that you have indeed been employed in this house?”

Chance answered very deliberately: “I have always been the gardener here. I have worked in the garden in back of the house all my life. As long as I can remember. I was a little boy when I began. The trees were small, and there were practically no hedges. Look at the garden now.”

Mr. Franklin quickly interrupted. “But there is not a single indication that a gardener has been living in this house and working here. We, that is—Miss Hayes and I—have been put in charge of the deceased’s estate by our firm. We are in possession of all the inventories. I can assure you,” he said, “that there is no account of your being employed. It is clear that at no time during the last forty years was a man employed in this house. Are you a professional gardener?”

“I am a gardener,” said Chance. “No one knows the garden better than I. From the time I was a child, I am the only one who has ever worked here. There was someone else before me—a tall black man; he stayed only long enough to tell me what to do and show me how to do it; from that time, I have been on my own. I planted some of the trees,” he said, his whole body pointing in the direction of the garden, “and the flowers, and I cleaned the paths and watered the plants. The Old Man himself used to come down to sit in the garden and read and rest there. But then he stopped.”

Mr. Franklin walked from the window to the desk. “I would like to believe you, Mr. Chance,” he said, “but, you see, if what you say is true, as you claim it to be, then—for some reason difficult to fathom—your presence in this house, your employment, hasn’t been reco

rded in any of the existing documents. True,” he murmured to his assistant, “there were very few people employed here; he retired from our firm at the age of seventy-two, more than twenty-five years ago, when his broken hip immobilized him. And yet,” he said, “in spite of his advanced age, the deceased was always in control of his affairs, and those who were employed by him have always been properly listed with our firm—paid, insured, et cetera. We have a record, after Miss Louise left, of the employment of one ‘imported’ maid, and that’s all.”

“I know old Louise; she can tell you that I have lived and worked here. She was here ever since I can remember, ever since I was little. She brought my food to my room every day, and once in a while she would sit with me in the garden.”

“Louise died, Mr. Chance,” interrupted Franklin.

“She left for Jamaica,” said Chance.

“Yes, but she fell ill and died recently,” Miss Hayes explained.

“I did not know that she had died,” said Chance quietly.

“Nevertheless,” Mr. Franklin persisted, “anyone ever employed by the deceased has always been properly paid, and our firm has been in charge of all such matters; hence our complete record of the estate’s affairs.”

“I did not know any of the other people working in the house. I always stayed in my room and worked in the garden.”

“I’d like to believe you. However, as far as your former existence in this house is concerned, there just isn’t any trace of you. The new maid has no idea of how long you have been here. Our firm has been in possession of all the pertinent deeds, checks, insurance claims, for the last fifty years.” He smiled. “At the time the deceased was a partner in the firm, some of us were not even born, or were very, very young.” Miss Hayes laughed. Chance did not understand why she laughed.