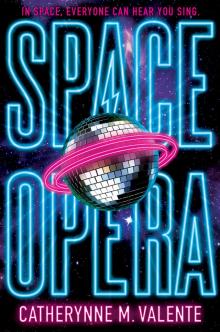

Space Opera

Catherynne M. Valente

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

Publisher’s Notice

The publisher has provided this ebook to you without Digital Rights Management (DRM) software applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This ebook is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this ebook, or make this ebook publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this ebook except to read it on your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: simonandschuster.biz/online_piracy_report.

For Heath,

Intergalactic glamrock ambassador to Earth

Earth

It’s the Arockalypse

Now bare your soul.

—“Hard Rock Hallelujah,” Lordi

1.

Boom Bang-a-Bang

Once upon a time on a small, watery, excitable planet called Earth, in a small, watery, excitable country called Italy, a soft-spoken, rather nice-looking gentleman by the name of Enrico Fermi was born into a family so overprotective that he felt compelled to invent the atomic bomb. Somewhere in between discovering various heretofore cripplingly socially anxious particles and transuranic elements and digging through plutonium to find the treat at the bottom of the nuclear box, he found the time to consider what would come to be known as the Fermi Paradox. If you’ve never heard this catchy little jingle before, here’s how it goes: given that there are billions of stars in the galaxy quite similar to our good old familiar standby sun, and that many of them are quite a bit further on in years than the big yellow lady, and the probability that some of these stars will have planets quite similar to our good old familiar knockabout Earth, and that such planets, if they can support life, have a high likelihood of getting around to it sooner or later, then someone out there should have sorted out interstellar travel by now, and therefore, even at the absurdly primitive crawl of early-1940s propulsion, the entire Milky Way could be colonized in only a few million years.

So where is everybody?

Many solutions have been proposed to soothe Mr. Fermi’s plaintive cry of transgalactic loneliness. One of the most popular is the Rare Earth Hypothesis, which whispers kindly: There, there, Enrico. Organic life is so complex that even the simplest algae require a vast array of extremely specific and unforgiving conditions to form up into the most basic recipe for primordial soup. It’s not all down to old stars and the rocks that love them. You’ve gotta get yourself a magnetosphere, a moon (but not too many), some gas giants to hold down the gravitational fort, a couple of Van Allen belts, a fat helping of meteors and glaciers and plate tectonics—and that’s without scraping up an atmosphere or nitrogenated soil or an ocean or three. It’s highly unlikely that each and every one of the million billion events that led to life here could ever occur again anywhere else. It’s all just happy coincidence, darling. Call it fate, if you’re feeling romantic. Call it luck. Call it God. Enjoy the coffee in Italy, the sausage in Chicago, and the day-old ham sandwiches at Los Alamos National Laboratory, because this is as good as high-end luxury multicellular living gets.

The Rare Earth Hypothesis means well, but it’s colossally, spectacularly, gloriously wrong.

Life isn’t difficult, it isn’t picky, it isn’t unique, and fate doesn’t enter into the thing. Kick-starting the gas-guzzling subcompact go-cart of organic sentience is as easy as shoving it down a hill and watching the whole thing spontaneously explode. Life wants to happen. It can’t stand not happening. Evolution is ready to go at a moment’s notice, hopping from one foot to another like a kid waiting in line for a roller coaster, so excited to get on with the colored lights and the loud music and the upside-down parts, it practically pees itself before it even pays the ticket price. And that ticket price is low, low, low. U-Pick-Em inhabitable planets, a dollar a bag! Buy-one-get-one specials on attractive and/or menacing flora and fauna! Oxygen! Carbon! Water! Nitrogen! Cheap! Cheap! Cheap! And, of course, all the intelligent species you can eat. They spin up overnight, hit the midway of industrial civilization, and ride the Giant Dipper Ultra-Cyclone till they puke themselves to death or achieve escape velocity and sail their little painted plastic bobsleds out into the fathomless deep.

Lather, rinse, repeat.

Yes, life is the opposite of rare and precious. It’s everywhere; it’s wet and sticky; it has all the restraint of a toddler left too long at day care without a juice box. And life, in all its infinite and tender intergalactic variety, would have gravely disappointed poor gentle-eyed Enrico Fermi had he lived only a little longer, for it is deeply, profoundly, execrably stupid.

It wouldn’t be so bad if biology and sentience and evolution were merely endearing idiots, enthusiastic tinkerers with subpar tools and an aesthetic that could be called, at best, cluttered and, at worst, a hallucinogenic biohazard-filled circus-cannon to the face. But, like the slender, balding father of the atomic age, they’ve all gotten far too much positive feedback over the years. They really believe in themselves, no matter how much evidence against piles up rotting in the corners of the universe. Life is the ultimate narcissist, and it loves nothing more than showing off. Give it the jankiest glob of fungus on the tiniest flake of dried comet-vomit wheeling drunkenly around the most underachieving star in the middle of the most depressing urban blight the cosmos has to offer, and in a few billion years, give or take, you’ll have a teeming society of telekinetic mushroom people worshipping the Great Chanterelle and zipping around their local points of interest in the tastiest of lightly browned rocket ships. Dredge up a hostile, sulfurous silicate lava sink slaloming between two phlegmy suns well into their shuffleboard years, a miserable wad of hell-spit, free-range acid clouds, and the gravitational equivalent of untreated diabetes, a stellar expletive that should never be forced to cope with something as toxic and flammable as a civilization, and before you can say no, stop, don’t, why? the place will be crawling with postcapitalist glass balloons filled with sentient gases all called Ursula.

Yes, the universe is absolutely riddled with fast-acting, pustulant, full-blown life.

So where is everybody?

Well, just at the moment when Enrico Fermi was walking to lunch with his friends Eddie and Herbert at Los Alamos National Laboratory, chatting about the recent rash of stolen city trash bins and how those “aliens” the blind-drunk hayseeds over in Roswell kept flapping their jaws about had probably gone joyriding and swiped them like a bunch of dropouts knocking over mailboxes with baseball bats, just then, when the desert sun was so hot and close overhead that for once Enrico was glad he’d gone bald so young, just then, when he looked up into the blue sky blistering with emptiness and wondered why it should be quite as empty as all that, just at that moment, and, in fact, up until fairly recently, everybody was terribly distracted by the seemingly inevitable, white-hot existential, intellectual, and actual obliteration of total galactic war.

Life is beautiful and life is stupid. This is, in fact, widely regarded as a universal rule not less inviolable than the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the Uncertainty Principle, and No Post on Sundays. As long as you keep that in mind, and never give more weight to one than the other, the history of the galaxy is a simple tune with lyrics flashed o

n-screen and a helpful, friendly bouncing disco ball of all-annihilating flames to help you follow along.

This book is that disco ball.

Cue the music. Cue the lights.

Here’s what you have to understand about intergalactic civil wars: they’re functionally identical to the knockdown, door-slamming, plate-smashing, wall-penetrating, shriek-sobbing drama of any high-strung couple you’ve ever met. The whole business matters a great deal to those involved and far, far less than the pressing issue of what to have for lunch to anyone outside their blast radius. No one can agree on how it started or whose fault it was, no one cares about the neighbors trying to bloody well sleep while it’s banging on, and not one thing in heaven or on Earth matters half as much as getting the last word in the end. Oh, it was all innocence and discovery and heart-shaped nights on the sofa at first! But then someone didn’t do the laundry for two weeks, and now it’s nothing but tears and red faces and imprecations against one person or the other’s slovenly upbringing and laser cannons and singularity-bombs and ultimatums and hollering, I never want to see you again, I really mean it this time or You’re really just like your mother or What do you mean you vapor-mined the Alunizar homeworld—that’s a war crime, you monster, until suddenly everyone’s standing in the pile of smoking rubble that has become their lives wondering how they’ll ever get their security deposit back. It’s what comes of cramming too much personality into too little space.

And there is always too little space.

But in the end, all wars are more or less the same. If you dig down through the layers of caramel corn and peanuts and choking, burning death, you’ll find the prize at the bottom and the prize is a question and the question is this: Which of us are people and which of us are meat?

Of course we are people, don’t be ridiculous. But thee? We just can’t be sure.

On Enrico Fermi’s small, watery planet, it could be generally agreed upon, for example, that a chicken was not people, but a physicist was. Ditto for sheep, pigs, mosquitoes, brine shrimp, squirrels, seagulls, and so on and so forth on the one hand, and plumbers, housewives, musicians, congressional aides, and lighting designers on the other. This was a fairly easy call (for the physicists, anyway), as brine shrimp were not overly talkative, squirrels failed to make significant headway in the fields of technology and mathematics, and seagulls were clearly unburdened by reason, feeling, or remorse. Dolphins, gorillas, and pharmaceutical sales representatives were considered borderline cases. In the final tally, Homo sapiens sapiens made the cut, and no one else could get served in the higher-end sentience establishments. Except that certain members of the clade felt that a human with very curly hair or an outsize nose or too many gods or not enough or who enjoyed somewhat spicier food or was female or just happened to occupy a particularly nice bit of shady grass by a river was no different at all than a wild pig, even if she had one head and two arms and two legs and no wings and was a prize-winning mathematician who very, very rarely rolled around in mud. Therefore, it was perfectly all right to use, ignore, or even slaughter those sorts like any other meat.

No one weeps for meat, after all.

If that one blue idiot ball had such trouble solving the meat/people equation when presented with, say, a German and a person not from Germany, imagine the consternation of the Alunizar Empire upon discovering all those Ursulas floating about on their cut-rate lavadump, or the Inaki, a species of tiny, nearly invisible parasitic fireflies capable of developing a sophisticated group consciousness, provided enough of them were safely snuggled into the warm chartreuse flesh of a Lensari pachyderm. Imagine the profound existential annoyance of those telekinetic sea squirts who ruled half the galaxy when their deep-space pioneers encountered the Sziv, a race of massively intelligent pink algae who fast-forwarded their evolutionary rise up the pop charts with spore-based nanocomputers, whose language consisted of long, luminous screams that could last up to fourteen hours and instantly curdle any nearby dairy products. And how could anyone be expected to deal with the Hrodos with a straight face when the whole species seemed to be nothing more than a very angry sort of twilit psychic hurricane occurring on one measly gas giant a thousand light-years from a decent dry cleaner?

None of them, not to mention the Voorpret or the Meleg or the 321 or any of the rest of the nonsense that wave after wave of intrepid explorers found wedged between the couch cushions of the galaxy, could possibly be people. They looked nothing like people. Nothing like the Aluzinar, those soft, undulating tubes of molten Venetian glass sailing through the darkness in their elegant tuftships. Not a bit like the majestic stone citizens of the Utorak Formation or the glittering secretive microparticulate of the Yüz, and certainly nothing remotely resembling the furry-faced, plush-tailed, time-traveling drunkards of the Keshet Effulgence, who looked improbably similar to the creatures humans called red pandas (which were neither red nor pandas, but there’s language for you), nor any of the other species of the Right Sort. These new, upstart mobs from the outlying systems were most definitely meat. They were fleas and muck and some kind of weird bear, in the case of the Meleg, and in the case of the Voorpret, pestilent, rotting viruses that spoke in cheerful puns through the decomposing mouths of their hosts. Even the 321, a society of profanity-prone artificial intelligences accidentally invented by the Ursulas, unleashed, reviled, and subsequently exiled to the satellite graveyards of the Udu Cluster, were meat, if somewhat harder to digest, being mainly made of tough, stringy math. Not that the globby lumps of the Alunizar were any less repulsive to the Sziv, nor did the hulking, plodding Utorak seem any less dangerously stupid to the 321.

Honestly, the only real question contemplated by either side was whether to eat, enslave, shun, keep them as pets, or cleanly and quietly exterminate them all. After all, they had no real intelligence. No transcendence. No soul. Only the ability to consume, respirate, excrete, cause ruckuses, reproduce, and inspire an instinctual, gamete-deep revulsion in the great civilizations that turned the galaxy around themselves like a particularly hairy thread around a particularly wobbly spindle.

Yet this meat had ships. Yet they had planets. Yet, when you pricked them, they rained down ultraviolet apocalyptic hellfire on all your nice, tidy moons. Yet this meat thought that it was people and that the great and ancient societies of the Milky Way were nothing but a plate of ground chuck. It made no sense.

Thus began the Sentience Wars, which engulfed a hundred thousand worlds in a domestic dispute over whether or not the dog should be allowed to eat at the dinner table just because he can do algebra and mourn his dead and write sonnets about the quadruple sunset over a magenta sea of Sziv that would make Shakespeare give up and go back to making gloves like his father always wanted. It did not end until about . . . wait just a moment . . . exactly one hundred years ago the Saturday after next.

When it was all done and said and shot and ignited and vaporized and swept up and put away and both sincerely and insincerely apologized for, everyone left standing knew that the galaxy could not bear a second go at this sort of thing. Something had to be done. Something mad and real and bright. Something that would bring all the shattered worlds together as one civilization. Something significant. Something elevating. Something grand. Something beautiful and stupid. Something terribly, gloriously, brilliantly, undeniably people.

Now, follow the bouncing disco ball. It’s time for the chorus.

2.

Rise Like a Phoenix

Once upon a time on a small, watery, excitable planet called Earth, in a small, watery country called England (which was bound and determined never to get too excited about anything), a leggy psychedelic ambidextrous omnisexual gendersplat glitterpunk financially punch-drunk ethnically ambitious glamrock messiah by the name of Danesh Jalo was born to a family so large and benignly neglectful that they only noticed he’d stopped coming home on weekends when his grandmother was nearly run over with all her groceries in front of the Piccadilly Square tube station, stunned into s

lack-jawed immobility by the sight of her Danesh, twenty feet high, in a frock the color of her customary afternoon sip of Pernod, filling up every centimeter of a gargantuan billboard. His black-lit tinsel-contoured face stared right back at her from behind the words: DECIBEL JONES AND THE ABSOLUTE ZEROS LIVE AT THE HIPPODROME: SOLD OUT! Somewhere in between popping out of his nineteenth-century literature course at Cambridge for cigarettes and never coming back and digging through the £1 bin at London’s shabbier thrift shops hunting for every last rhinestone, sequin, or lurid eye shadow duo, he had found the time to invent the entire electro-funk glamgrind genre from scratch and become the biggest rock star in the world.

For about half a minute, give or take.

It’s a song as old as recorded sound, and you already know how it goes: given that there are billions of people on the planet, and that a really quite unsettling number of them are musicians, and the suicide-inducing low probability of paying even one electric bill via the frugal application of three chords and a clever lyric, and that such musicians, if they can produce anything good, have a high likelihood of getting around to it sooner or later, and the breakneck speed at which a digitally entangled global population fueled by faster-than-instantaneous gratification consumes units of culture, then being the biggest rock star in the world is highly likely to be a short-lived gig with no snacks served at intermission, and even at the absurdly primitive crawl of Earth’s collective attention span, any successful front man is guaranteed, sooner or later, to wake up on the floor of his flat with a sucking black hole of a hangover and a geologically terrible haircut asking: Where is everybody?

Many solutions to this conundrum of mid-list musical misery have been tried: a comeback solo album, a reunion tour, licensing one’s former incandescent hits for mid-priced car commercials, a solid redemption arc on a reality television program, a shocking memoir, giving up on dignity and taking a run at Eurovision, a quieter but steady career in children’s film sound tracks, focusing on one’s family, charity work, a crippling heroin addiction, acting, a sex scandal, public alcoholism, producing, or sudden violent death.