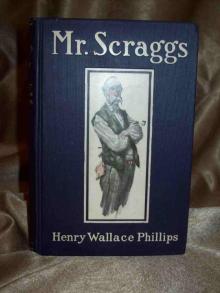

Mr. Scraggs

Henry Wallace Phillips

Produced by Al Haines

MR. SCRAGGS

INTRODUCED BY RED SAUNDERS

By

HENRY WALLACE PHILLIPS

Author of "Red Saunders," "Plain Mary Smith," etc.

THE GRAFTON PRESS

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1903, 1904, 1905, by The Curtis Publishing Co.Copyright, 1903, by S. S. McClure Co. Copyright, 1905, by TheGrafton Press

Published January, 1906 Second edition February, 1906

CONTENTS

I. BY PROXY II. IN THE TOILS III. ST. NICHOLAS SCRAGGS IV. THE SIEGE OF THE DRUG STORE V. THE MOURNFUL NUMBER VI. MR. SCRAGGS INTERVENES VII. THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"Made any other human countenance I ever see look like anigger-minstrel show"

"He was disappointed in love--he had to be"

"Scraggsy looked like a forlorn hope lost in a fog"

"'Dearly beloved Brethren,' says I"

"Put up a high-grade article of cat-fight"

"You will talk to my ol' man like that, will you?"

"So we rode in, right cheerful"

"I was all over that Injun"

MR. SCRAGGS

INTRODUCED BY RED SAUNDERS

BY PROXY

I had met Mr. Scraggs, shaken him by the hand, and, in the shallowsense of the word, knew him. But a man is more than clothes and abald head. It is also something of a trick to find out more abouthim--particularly in the cow country. One needs an interpreter.Red furnished the translation. After that, I nurtured Mr.Scraggs's friendship, for the benefit of humanity and philosophy.Saunders and I lay under a bit of Bad Lands, soaking in the springsun, and enjoying the first cigarette since breakfast. In regardto things in general, he said:

"Now, there was the time I worked for the Ellis ranch. A ranch islike a man: it has something that belongs to it, that don't belongto no other ranch, same as I have just the same number of eyes andnoses and so forth that you drew on your ticket, yet you ain't meno more'n I'm you. This was a kind of sober-minded concern; it wasa thoughtful sort of a ranch, where everybody went about his workquiet. I guess it was because the boys was mostly old-timers,given to arguing about why was this and how come that. Argue!Caesar! It was a regular debating society. Wind-river Smithpicked up a book in the old man's room that told about the Injunsbein' Jews 'way back before the big high-water, and how one gang of'em took to the prairie and the other gang to the bad clothesbusiness. Well, he and Chawley Tawmson--'member Chawley and histooth? And you'd have time to tail-down and burn a steer beforeChawley got the next word out--well, they got arguin' about whetherthis was so, or whether it weren't so. Smithy was for the book,havin' read it, and Chawley scorned it. The argument lasted amonth, and as neither one of 'em knew anything about an Injun,except what you can gather from looking at him over a rifle sight,and as the only Jew either one of 'em ever said two words to wasthe one that sold Windriver a hat that melted in the firstrain-storm, and then him and Chawley went to town and made theHebrew eat what was left of the hat, after refunding the price, youcan imagine what a contribution to history I listened to. That'sthe kind of place the Ellis ranch was, and a nice old farm she was,too.

"I'd been working there about three months, when along come a manthat looked like old man Trouble's only son. Of all the sorrowfulfaces you ever see, his was the longest and thinnest. It made anyother human countenance I ever see look like a nigger-minstrel show.

Made any other human countenance I ever see looklike a nigger-minstrel show.]

"We was short-handed, as the old man had begun to put up hay andwork some of the stock in corrals for the winter, so we took ournew brother on. His name was Ezekiel George WashingtonScraggs--tuneful number for a cow-outfit!--and his name didn't comeanywhere near doin' him justice at that. Ezekiel knew his biz andturned in a day's work right straight along, but when you'd say,'Nice day, Scraggs?' he'd heave such a sigh you could feel thedraft all the way acrost the bull-pen, and only shake his head.

"Up to this time Wind-river had enjoyed a cinch on the mournfulact. He'd had a girl sometime durin' the Mexican war, and she'dborrowed Smith's roll and skipped with another man. So, if wecrowded Smithy too hard in debate, he used to slip behind that girland say, 'Oh, well! You fellers will know better when you've hadmore experience," although we might have been talkin' about what'sbest for frost-bite at the time.

"He noticed this new man Scraggs seemed to hold over him a triflein sadness, and he thought he'd find out why.

"'You appear to me like a man that's seen trouble,' says he.

"'Trouble!' says Scraggs. 'Trouble!' Then he spit out of the doorand turned his back deliberate, like there wasn't any useconversin' on the subject, unless in the presence of an equal.

"Scraggs was a hard man to break into, but Smithy scratched hishead and took a brace.

"'I've met with misfortune myself,' says he.

"'Ah?' says Scraggs. 'What's happened to you?' He sounded as ifhe didn't believe it amounted to much, and Smithy warmed up. Heladled out his woes like a catalogue. How he'd been blew up inmines; squizzled down a mountain on a snow-slide; chawed by a bear;caught under a felled tree; sunk on a Missouri River steamboat, andher afire, so you couldn't tell whether to holler for thelife-savers or the fire-engine; shot up by Injuns and personalfriends; mistook for a horse-thief by the committee, and much else,closing the list with his right bower. 'And, Mr. Scraggs, I haveput my faith in woman, and she done me to the tune of all I had.'

"'_Have_ you?' says Scraggs, still perfectly polite anduninterested. "'_Have_ you?' says he, removin' his pipe andspitting carefully outdoors again. And then he slid the jokera'top of Smithy's play. 'Well, _I_ have been a Mormon,' says he.

"'What?' says all of us.

"'Yessir!' says Mr. Scraggs, getting his feet under him, and with amournful pride I can't give you the least idea of. 'A Mormon; noneof your tinkerin' little Mormonettes. I was ambitious; hence E. G.W. Scraggs as you now behold him. In most countries a man'sstandin' is regulated by the number of wives he ain't got; in Utahit's just the reverse--and a fair test, too, when you come to thinkof it. I wanted to be the head of the hull Mormon kingdom, so Imarried right and left. Every time I added to the available supplyof Mrs. Scraggs, I went up a step in the government. I ain't allthe persimmons for personal beauty, so I had to take what waswillin' to take me, and they turned out to be mostly black-eyedwomen with peculiar dispositions. Gentlemen, I was once as livelyand happy a little boy as ever did chores on a farm. See me now!This is the result of mixin' women and politics. If I should tellyou all the kinds of particular and general devilment (to run 'emalphabetically, as I did to keep track of 'em) that Ann ElizaScraggs, and Bridget Scraggs, and Belle Scraggs, and Fanny Scraggs,and Honoria and Helen Scraggs, and Isabelle Scraggs, and so on upto zed, raised with me, it would go through any little germs of joyyou may have in your constitutions like Sittin' Bull's gang ofdog-soldiers through an old ladies' sewing bee. Look at me! Forall them years that cussed ambition of mine held me in its deadlytoils. I never heard the sound of blessed silence. Trouble! I'mbald as a cake of ice; my nerves is ruined. If the wind makes anoise in the grass like the swish of skirts, I'm a mile up thetrack before I get my wits back, sweatin' coldly and profusely,like a water-cooler.

"'I ain't got anything to tie to but all them women by the name ofScraggs, and them ties I cut by travelin' fast between daylights.Wisht I could introduce you to Mrs. Scraggs as she inhabits theterritory of Utah--you'd understand a power of things that may seema little misty to you at present. However, I can't do that, nor Iwouldn't neither, if I was to be made general superintendent of thewhole show for my pains. I'll leave the aggregated Mrs. Sc

raggs inthe hands of Providence, as bein' the only power capable ofhandling her. Yet I don't believe in Providence. I don't believein no Hereafter, nor Heretofore, nor no Now; I don't believe in noEast nor West, nor Up nor Down, nor Sideways, Lengthways,'Cross-the-center, Top, Bottom, or Middle. I have lost my faith inevery ram-butted thing a man can hear, see, or touch, includin'everything I've left out. That's me, Joe Bush.' He stopped aminute. 'Trouble--' says he. 'Trouble--I wisht nobody'd mentionthat word in my hearin' again.'

"Well, he had us gummed fast, all right. Nobody in our outfitcould push up against such a world-without-end experience as that.

"But Scraggs was a gentleman; he didn't crowd us because we broke.In fact, now that he'd had his say, he loosened up considerable,and every now and then he'd even smile.

"Then come to us the queerest thing in that whole curiosity-shop ofa ranch. Its name was Alexander Fulton. I reckon Aleck was abouttwenty-one by the almanac, and anywhere's from three to ninety bythe way you figure a man. Aleck stood six foot high _as_ he stood,but if you ran the tape along his curves he was about six-foot-four.

"He weighed one hundred and twenty pounds, of which twenty-fivewent to head and fifty to feet. Feet! You never saw such feet.They were the grandest feet that ever wore a man; long and high andwide, and all that feet should be. Chawley said that Alexander hadground plan enough for a company of nigger soldiers. And hung toAleck's running gear, they reminded you of the swinging jigger in aclock. They almost make me forget his hands. When Aleck laid aflipper on a cayuse's back, you'd think the critter was blanketed.And then there was his Adam's apple--he had so many specialfeatures, it's hard to keep track of them. About a foot of Aleck'sprotrudin' into air was due to neck. In the center of that neckwas an Adam's apple that any man might be proud of.

"His complexion consisted of freckles; when you spoke to him suddenhe blushed, and then he looked for all the world like a stormysunset. His eyes were white, and so was his hair, and so was poorold Aleck--as white a kid as they make 'em, and, beyond guessing,the skeeriest--not relatin' to things, but to people. How he cometo drift out into our country was a story all by itself. He wasdisappointed in love--he _had_ to be. One look at him and you'dknow why. So he sailed out to the wild West, where he was about asuseful as a trimmed nighty. We always stood between Aleck and theold man, until the boy got so he'd make straight once out of apossible five.

He was disappointed in love--he _had_ to be.]

"First off, he was still; then, findin' himself in a confidentialcrowd, and bustin' to let us know, his trouble, he told us allabout it. He'd never spoke to the girl, it seems, more'n to say,'How-d'ye-do, ma'am,' and blush, and sit on his hat, and makecurious moves with them hands and feet; but there come anotherfeller along, and Alexander quit.

"'You got away?' says Scraggs. 'Permit me to congratulate you,sir!' And he took hold of as much of Aleck's right wing as hecould gather, and shook it hard. 'Alas!' says he, 'how differentis the tale I have to tell.'

"'But I didn't want to come away!' stutters Alexander.

"'Didn't want to?' cries Scraggs, letting the pipe fall out of hismouth. Then he turns to me and taps his brow with his finger,casting a pitying eye on Aleck.

"As time went on Aleck got worse and worse. He had a case ofingrowing affection; it cut his weight down to ninety pounds. Withhim leaving himself at that rate, you could take pencil and paperand figure to the minute when Alexander Fulton was booked to crossthe big divide. And we liked the kid. In spite of his magnificentfeet, and his homeliness, and his thumb-handsidedness, I got tofeel sort of as if he was my boy--though if ever I have a boy likeAleck, I put in my vote for marriage being a failure, andeverything lost, honor and all. Probably it was more as if he wasa puppy-dog, or some other little critter that couldn't take careof itself. Anyhow, we got worked up about the matter, and talkedit over considerable when he was out of hearing. It come to this:there was no earthly use in trying to get Aleck to go back and makea play at the girl. He'd ha' fell dead at the thought of it. Thatleft nothing but to bring the girl to Aleck. You see, we thoughtif we told the young woman that here was a decent honestman--hurrying over the rest of the description--just evaporatingfor love of her, that she might be persuaded to come out and marryhim. We weren't going to let our pardner slip away without aneffort anyhow. We couldn't do no less than try. Then come theproblem of who was the proper party to act as messenger. The restof us, without bothering him by taking him into our confidence,decided that Scraggs was the proper man, because, if he didn't knowWomen and her Ways, the subject belonged to the lost arts.

"But, man! Didn't he r'ar when we told him!

"'ME go after a woman!' says he. '_ME_!!!--Take another drink!'But we labored with him. Told about what a horrible time he'dhad--he always liked to hear about it--and how there wasn't anybodyelse fit to handle his discard in the little game of matrimony--andwhat was the use of sending a man that would break at the firstwire fence? If we was going to do the thing, we wanted to do it;and so forth and so forth, till we had him saddled and bridled andstanding in the corner of the corral as peaceful as a soldier'smonument, for he was the best-hearted old cuss under his crust thatever lived.

"'All right,' says he. 'I'll do it, and it's "Get there, Eli!"when I hook dirt. Poor old Aleck is as good as married, and theLord have mercy on his soul! But there's one thing I wish tostate: I'm running the job, and I run it my own way. I don't wantany interfering nor no talk afterward--'s that understood?

"It was. He was to cut loose.

"'All right,' says he. 'Poor Aleck!' So that night E. G. W.Scraggs took his cayuse and made for the railroad station, boundeast.

"Aleck had give us full details. We knew all about his little townand about that house in particular; just how the morning-gloriesgrew over the back porch, looking out on the garden patch, andwhere the cistern was, which, with his usual good luck, Aleck hadmanaged to fall into, whilst they were putting a new cover on it.Yessir; we knew that little East Dakota town as well as if we'dbeen raised there; but we were some shy on details concerning thegirl. I swear I don't believe Aleck had ever looked her full inthe face. She was medium height, plump, blue eyes, brown hair, andthat ended the description,

"We suffered any quantity from impatience before E. G. W. showedup. You see, there ain't such a lot that happens to other peopleoccurrin' on a ranch, and we was really more excited over Aleck andhis girl than a tenderfoot would be over a gun fight, and for thesame reason; it was out of our ordinary.

"Scraggsy didn't keep us on the anxious seat. He was the surestthing I ever saw. Often I've watched him rope a critter; he neverwhirled his rope, even when riding--always snapped. And he nevermade a quick move--that is, a move that looked in a hurry--all thesame, every time he let go of the rope, there was his meat on theother end of it. Women was the only thing that did E. G. W.Scraggs, and that's because he wholesaled the business. Thatambition of his wrecked him. When he trotted around the track forfun, nobody else in the heat could see him for the dust.

"One evening about half-past eight, when the glow was still strong,here come Scraggs, prompt to the schedule. He was riding and abuggy trailed behind him.

"We chased Aleck over to the main house, where the old man, whostood in on the play, was to keep him busy until called for.

"Then up pulls E. G. W. and the buggy. In the buggy was a youngwoman, and a man.

"'Here we are,' says Scraggs, in the tone of one who has done hispainful duty. 'Check the outfit--one girl and one splicer--haveyou kept holt of Aleck?'

"'Yes,' I says. 'We've got him--come in, folks.' I was crazy tohear how he'd pulled it off. Soon's they got inside I lugged himto the corner, leaving the other boys to welcome the guests. 'Tellme about it,' I says.

"'Short story,' says he. 'Moment I got off the choo-choo I spottedthe house--couldn't mistake it. Laid low in the daytime andscouted around as soon as night come. Girl goes down to the barnand comes back with a pail

of milk. I grabbed her and put my handover her mouth so's she couldn't holler. "Now listen," I says toher. "There's a friend of mine wants to marry you. When I let yougo, you'll skip into the house and pick up what clothes is handy,and you'll vamoose this ranch at quarter of eleven, sharp, so wecan make the next train west. If you ain't there, or if you say asingle word to a human being--you see this?" and I stuck the end ofmy hoss-pistol under her nose. "Well, I'll blow the head clean offyour shoulders with it." Then I laid back my ears and rolled myeyes around. Well, sir, she was scart so's she didn't knowanything but what I said. I hated to treat a lady like that, butif I've learned anything concerning handlin' the sect, it'sthis--you got to be firm. There's where I made my mistakeformerly. Then I let go of her and went back to the deppo. Whatshe thought I couldn't even guess, but I knew I was goin' to havecompany, and, sure enough, 'bout three minutes before train time,here comes our friend. When I got her safe aboard I told her sheneedn't be scart. Lots worse things could happen to her thanmarryin' Aleck, and she says "yessir," and she kept on sayin'"yessir" to all I told her.--Wisht I could have found one likethat, instead of eighty of 'em that stood ready to jump down mythroat the minute I opened my mouth.--She told me she'd had amiddlin' hard time of it and didn't mind a change. That surprisedme a little, because I jedged from Aleck's talk she was anupstandin' critter--but, pshaw! Aleck would think a worm was asassy thing if it squirmed in his direction. Then I telegraphedCon Foster to have me a buggy and a minister ready for the threeo'clock train, and to keep his yawp calked up. So as soon as I hitland again, there was the rig complete; we hopped in and starteda-coming at once and fast, and here we are; for which I raisethanks, and all the curses of the Mormon gods be on the head of theman that gets me into such a play as this again! Snake old Aleckout and get the misery done with. That minister's chargin' mefifty cents an hour, and I don't know whether he's the real thingor not, at that. Con whispered in my ear that he worked in agrocery when he first struck town, dealt stud-poker for JohnnyEarly, quit that and took to school-teachin', then threw that upand preached. But what's the difference out here? He's expensive,anyhow, and all Con could find.'

"So I wagged my legs for the house and trotted Aleck down to thebull-pen.

"'Friend of yours there,' I told him.

"'That so?' says he. 'Who is it?'

"'Lady,' I says, kind of gay, thinkin' he'd be pleased.

"He stopped in his tracks. Then I remembered who I was talkin' to.

"'Come along, here, now!' says I, and nailed him by the neck. 'Youain't goin' to miss your happiness if main strength can give it toyou.' His toes touched about once to the rod. I run him into thepen.

"'There,' says I, 'is somebody you know.'

"Well, sir, old Aleck looked at the gal, and the gal looked atAleck, and the rest of us looked at each other. Soon's the kid gothis breath from the shock he yells, 'I never laid eyes on that ladybefore!'

"Oh, Hivins, Maria! That was the awfullest minute I ever livedthrough. Poor old E. G. W. S.! We all turned away from him, outof pity. He had the expression of a man that's fell down ahundred-foot prospect hole and been struck by lightning before hetouched bottom. He grabbed aholt of the minister and swallered andswallered, unable to chirp.

"At last he rallied. 'You mean to tell me, Aleck,' he says, in avoice hardly strong enough to get through his mustache, 'that I'vemade a mistake?'

"Aleck was always willing to believe he was wrong. 'I'm _pretty_sure, Zeke--I ain't never seen you, have I, Miss?'

"'No, sir--not that I know of,' answers the girl, with her eyes onthe ground.

"E. G. W. rubbed his brow.

"'Will you make good, anyhow, Aleck?' he coaxed. 'I got theminister and all right here--it won't take a minute.'

"I'd let go of Aleck in the excitement. At these words he made onestep from where he stood in the house, through the window, to tenfoot out of doors, and a few more steps like that, and he was outof the question.

"Then the girl put her face in her hands and begun to cry. She wasa mighty pretty, innocent, plump little thing, and we'd rather havehad most anything than that she should stand there cryin'. But wewere all hung by the feet and wandering in our minds. The simplelife of the cow-puncher doesn't fit him to grapple with problemslike that.

"Then, sir, up gets Ezekiel George Washington Scraggs, master ofhimself and the situation.

"'Young lady,' says he, 'I have got you out here under falsepretenses. I'm as homely as a hedge fence, and my record is dottedwith marriages worse than a 'Pache outbreak with corpses andburning homes. I ain't any kind of proposition to tie up to a nicegirl like you, and I swear by my honor that nothing was furtherfrom my thoughts than matrimony--not meanin' any slur on you, forif I'd found you before, I might have been a happy man--Well, hereI stand: if you'll marry me, say the word!' By thunder, we gavehim a cheer that shook the roof. You can laugh if you like, but itwas a noble deed.

"The girl reached out her left hand--so help me Moses! She likedhim! I took a careful squint at old Scraggsy, in this new light,and I want to tell you that there was something kind of fine inthat long lean face of his, and when he took the girl's hand helooked like a gentleman.

"You wouldn't think that holding a gun to her head, and threatenin'to blow her brains out was just the touch that would set a maiden'sheart tremblin' for a man, but if a woman takes a fancy to you,your habits and customs, manners and morals, disposition, personalappearance, financial standing and way of doing things generally isonly a little matter of detail.

"'How will this figger out legally?' E. G. W. asked the minister.

"The minister, he was a cheerful, practical sort of lad, ready toindorse anything that would smooth the rugged road of life.

"'Do you renounce the Mormon religion?' he asks.

"'Bet your life,' says Scraggs. 'And all its works.'

"'That settles it,' says the minister. 'Besides, I don't thinkanybody will ever come poking out here to make trouble--wheneveryou say the word.'

"'One minute,' says Scraggs, and he turned to the girl very gentle.'Are you doing this of your own free will, and not because I luggedyou out here?'

"'Yessir,' says she.

"'You want me, just as I stand?'

"'Yessir.'

"'Keno. I won't forget it.' Then he put his hand on her head,took off his hat, and raised his face. 'O God!' he prays, 'youknow what a miserable time I've had in this line before. I admitit was nine-tenths my fault, but now I call for an honest deck andthe hands played above the table. And make me act decent for thesake of this nice little girl. Amen.' Then he pulled atwenty-dollar gold piece out of his pocket and plunked her downbefore the minister, 'Shoot,' says he. 'You're faded.'

"Well. there old Scraggs--I say 'old,' but the man weren't morethan forty--celebrated his eighty-first marriage in that oldbull-pen, and they lived as happy ever after as any story book.Which knocks general principles. Probably it was because that noman was ever treated whiter than she treated him, and no woman wasever treated whiter than he treated her; he had the knack of bein'awful good and loving to her, without being foolish. Experiencewill tell, and he'd experienced a heap of the other side.

"And now, what do you think of Aleck? The scare we threw into himthat night wound up his moanin' and grievin' about the other girl.He never cheeped once after that, but got fat and hearty, and whenI left the ranch he was makin' up to a widow with four children, asbold as brass. There was more poetry in E. G. W, than there was inAleck, after all."