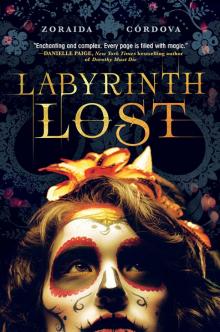

Labyrinth Lost

Zoraida Cordova

Thank you for purchasing this eBook.

At Sourcebooks we believe one thing:

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES.

We would love to invite you to receive exclusive rewards. Sign up now for VIP savings, bonus content, early access to new ideas we're developing, and sneak peeks at our hottest titles!

Happy reading!

SIGN UP NOW!

Also by Zoraida Córdova

The Vicious Deep

The Savage Blue

The Vast and Brutal Sea

Copyright © 2016 by Zoraida Córdova

Cover and internal design © 2016 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Nicole Komasinski/Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover images © shayne gray/500 Prime; lineartestpilot/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Contents

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Part I: The Bruja

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Part II: The Fall

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Part III: The One

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Back Cover

For Adriana and Ginelle Medina, my favorite brujitas.

Part I

The Bruja

1

Follow our voices, sister.

Tell us the secret of your death.

—Resurrection Canto, Book of Cantos

The second time I saw my dead aunt Rosaria, she was dancing.

Earlier that day, my mom had warned me, pressing a long, red fingernail on the tip of my nose, “Alejandra, don’t go downstairs when the Circle arrives.”

But I was seven and asked too many questions. Every Sunday, cars piled up in our driveway, down the street, and around the corner of our old, narrow house in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Mom’s Circle usually brought cellophane-wrapped dishes and jars of dirt and tubs of brackish water that made the Hudson River look clean. This time, they carried something more.

When my sisters started snoring, I threw off my covers and crept down the stairs. The floorboards were uneven and creaky, but I was good at not being seen. Fuzzy, yellow streetlight shone through our attic window and followed me down every flight until I reached the basement.

A soft hum made its way through the thin walls. I remember thinking I should listen to my mom’s warning and go back upstairs. But our house had been restless all week, and Lula, Rose, and I were shoved into the attic, out of the way while the grown-ups prepared the funeral. I wanted out. I wanted to see.

The night was moonless and cold one week after the Witch’s New Year, when Aunt Rosaria died of a sickness that made her skin yellow like hundred-year-old paper and her nails turn black as coal. We tried to make her beautiful again. My sisters and I spent all day weaving good luck charms from peonies, corn husks, and string—one loop over, under, two loops over, under. Not even the morticians, the Magos de Muerte, could fix her once-lovely face.

Aunt Rosaria was dead. I was there when we mourned her. I was there when we buried her. Then, I watched my father and two others shoulder a dirty cloth bundle into the house, and I knew I couldn’t stay in bed, no matter what my mother said.

So I opened the basement door.

Red light bathed the steep stairs. I leaned my head toward the light, toward the beating sound of drums and sharp plucks of fat, nylon guitar strings.

A soft mew followed by whiskers against my arm made my heart jump to the back of my rib cage. I bit my tongue to stop the scream. It was just my cat, Miluna. She stared at me with her white, glowing eyes and hissed a warning, as if telling me to turn back. But Aunt Rosaria was my godmother, my family, my friend. And I wanted to see her again.

“Sh!” I brushed the cat’s head back.

Miluna nudged my leg, then ran away as the singing started.

I took my first step down, into the warm, red light. Raspy voices called out to our gods, the Deos, asking for blessings beyond the veil of our worlds. Their melody pulled me step by step until I was crouched at the bottom of the landing.

They were dancing.

Brujas and brujos were dressed in mourning white, their faces painted in the aspects of the dead, white clay and black coal to trace the bones. They danced in two circles—the outer ring going clockwise, the inner counterclockwise—hands clasped tight, voices vibrating to the pulsing drums.

And in the middle was Aunt Rosaria.

Her body jerked upward. Her black hair pooled in the air like she was suspended in water. There was still dirt on her skin. The white skirt we buried her in billowed around her slender legs. Black smoke slithered out of her open mouth. It weaved in and out of the circle—one loop over, under, two loops over, under. It tugged Aunt Rosaria higher and higher, matching the rhythm of the canto.

Then, the black smoke perked up and changed its target. It could smell me. I tried to backpedal, but the tiles were slick, and I slid toward the circle. My head smacked the tiles. Pain splintered my skull, and a broken scream lodged in my throat.

The music stopped. Heavy, tired breaths filled the silence of the pulsing red dark. The enchantment was broken. Aunt Rosaria’s reanimated corpse turned to me. Her body purged black smoke, lowering her back to the ground. Her ankles cracked where the bone was brittle, but still she took a step. Her dead eyes gaped at me. Her wrinkled mouth growled my name: Alejandra.

She took another step. Her ankle turned and broke at the joint, sending her flying forward. She landed on top of me. The rot of her skin filled my nose, and grave dirt fell into my eyes.

Tongues clucked against crooked teeth. The voices of the circle hissed, “What’s the girl doing out of bed?”

There was the scent of extinguished candles and melting wax. Decay and perfume oil smothered me until they pulled the body away.

My mother jerked me up by the ear, pulling me up two flights of stairs

until I was back in my bed, the scream stuck in my throat like a stone.

“Never,” she said. “You hear me, Alejandra? Never break a Circle.”

I lay still. So still that after a while, she brushed my hair, thinking I had fallen asleep.

I wasn’t. How could I ever sleep again? Blood and rot and smoke and whispers filled my head.

“One day you’ll learn,” she whispered.

Then she went back down the street-lit stairs, down into the warm red light and to Aunt Rosaria’s body. My mother clapped her hands, drums beat, strings plucked, and she said, “Again.”

2

La Ola, Divina Madre of the Seas,

carry this prayer to your shores.

—Rezo de La Ola, Book of Cantos

When I wake from the memory, I can still smell the dead. My heart races, and a deep chill makes me shiver from head to toe. I remind myself that day happened nearly nine years ago, that I’m safe in my room, and it’s seven in the morning, and today is just another day.

That’s when I notice Rose, my little sister, standing over me.

“You were dreaming about Aunt Ro again,” she says in that way of hers. It’s almost impossible to lie to Rose. Not just because of her gifts, but also because she speaks with a quiet steel and those big, unwavering, brown eyes. She’s never the first one to look away. “Weren’t you?”

“Freak.” I put my hand on the side of her face and push her away. “Stay out of my head.”

“It’s not my fault,” she says, then mutters, “stank breath.”

I reach behind me to shut the window I cracked open when it was too hot in the middle of the night. It’s freezing for October, but a good excuse to bring out my favorite sweater.

Rose walks over to my altar, tucked away in the farthest corner of my attic bedroom, and pokes around my stuff. I rub the crud from my eyes and flick it at her.

“Don’t you have your own room now?” I ask.

My mom went into a redecorating fit over the summer when she suddenly realized our house hadn’t changed in six years. That it was too big and too empty and too something. Plus, three teenage girls fighting over one room was giving her gray hair.

“I could hear your dreams,” Rose says. “It gives me a headache.”

Rose, the youngest of us three, came into her powers much too early. Right now it’s small stuff like dream walking and spirit impressions, but psychic abilities are a rare gift for any bruja to have. We’ve never had the Sight in our family. Not that Mom’s ever heard of, at least.

“I can’t control my dreams,” I say.

“I know. But I woke up with a weird feeling this time.” She shrugs, runs her index finger across the thick layer of dust that cakes my altar. Out of all the brujas in this house, I’m not winning any awards for altar maintenance. A small, white candle is burned to the stub, and the pink roses I bought over the summer have shriveled to dust. There are two photos—one of my mom, Lula, Rose, and me at the beach, and one of my Birth Rites ceremony with Aunt Rosaria.

“Lula said to wake you up,” Rose says, rubbing the altar dust between her fingers. “We have to make the ambrosia before we leave for school. You also might want to clean your altar before the canto tonight.”

“Sure, sure,” I say dismissively. I busy myself in my closet, searching for my favorite sweater. I try to push back the swirl of anxiety that surges from my belly to my heart. “We both know she’s wasting her time, right? We’ve done three spells already and none of them have worked.”

“Maybe this one will,” Rose says. “Besides, you know Lula won’t rest until she gets what she wants.”

Funny how no one asks what I want.

Rose starts to leave, then stops at my door. She lifts her chin in the direction of the mess in my closet. “Lula was already here looking for something to wear, in case you were wondering.”

“Of course she was.” I roll my eyes and mentally curse my older sister. When I get to the bathroom, it’s locked. Now I have to wait for Lula to fluff her dark curls to perfection, then pick out all of her blackheads.

I bang on the door. “How many times do I have to tell you not to go in my room?”

There’s the click of the blow dryer shutting off. “Did you say something?”

“Come on. Hurry up!”

“Well, your fat ass should have gotten out of bed earlier! Chop, chop, brujita! We have a canto to prepare for.”

I bang my fist on the door again. “Your ass is fatter than mine!”

“I’m hungry,” Rose says.

I jump. Knowing how our floor creaks, I have no idea how she walks so quietly. “I hate when you sneak up behind me.”

“I wasn’t sneaking,” she mutters.

I want to get mad. Why can’t Lula be the one to make breakfast for a change? I just want a nice, hot shower to clear my head. I want to go through the motions of the day and pretend like we’re one normal, functional family. I look at Rose’s sweet face and resign myself to the burden of being the middle child.

“Come,” I tell Rose. I bang the bathroom door one last time. “And you better put my sweater back where you found it!”

In the kitchen, I grab all the ingredients I need while Rose sits at the table.

“Mom says if you guys keep fighting she’s going to take your voices with a Silencing Canto.”

“Then it’s a good thing she already left,” I mutter.

There’s a cereal bowl and spoon on the drying rack and a green votive candle next to my mom’s favorite good luck rooster. The candle makes the room smell like a forest, and it’s the only indication that my mom was here.

Since it’s a Monday morning, my mom’s already on a train into Manhattan, where she works at a gynecologist’s office. My mom, whose magical hands have safely delivered more babies than the freshly med-schooled doctors she files papers for, is a receptionist. That’s my mother’s calling: bringing souls into this world. Calling or no calling, a bruja’s got to pay the bills.

When I try to flip my first pancake, it sticks on the pan. My calling is not making pancakes. Unless it’s making bad pancakes, in which case, I’m on the right track.

Rose is already dressed and sitting at the kitchen table. “I want that one.”

“The burned one?” I flip it onto a blue plate and set it in front of her.

“It tastes good with syrup and butter.”

“You’re so odd.”

“That’s why you love me.”

“Who told you that?” I say, adding a smile and a wink.

Rose pulls her staticky, brown hair into a ponytail, but no matter how much we spray it or cover it in gel, little strands threaten to fly away. It comes with her powers—something about being extra charged with other worlds—but it sucks when you’re a poor girl from Brooklyn going to a super-ritzy junior high in Manhattan. Rose even gets a proper uniform. Lula and I never got uniforms. Then again, Rose is a genius, even compared to us. Lula barely passes, and even though I’m at the top of my class, I still got left back a year after—well, after my dad. I have high hopes for Rose to do more with herself. When I went to sleep, she was still awake and reading a textbook that is as incomprehensible to me as our family Book of Cantos.

Just then, Lula comes bouncing down the steps, a pop song belting out of her perfectly glossy, pink mouth. Her curls bounce as if her enthusiasm reaches right to her hair follicles. Her honey-brown skin looks gold in the soft morning light. Her gray eyes are filled with mischief just waiting to get out. Her smile is so bright and dazzling that I forget I’m mad at her for hogging the bathroom. Then I see she’s wearing my favorite sweater. It’s the color of eggnog and so soft it feels like wearing a cloud.

“I want funny shapes.” She pecks a kiss on my cheek.

“You’re a funny shape,” I tell her.

I make Lula�

�s pancakes, this time too mushy in the center. I throw the plate in front of her and leave a stack for myself.

“I thought you were starting on the ambrosia,” Lula says, annoyed.

She has zero right to be annoyed right now.

“Someone has to feed Rose,” I say matter-of-factly.

Lula shakes her head. “Ma works really hard. You know that.”

“I didn’t say she doesn’t work hard,” I say defensively.

“Whatever, let’s just get this done before Maks gets here.” Lula walks down the hall to the closet where we keep our family altar and grabs our Book of Cantos. It has every spell, prayer, and piece of information that our ancestors have collected from the beginning of our family line. Even when the Book falls apart after a few decades, it gets mended, and we just keep adding to it.

“Yeah, wouldn’t want to keep Captain Hair Gel waiting,” I say.

Rose snickers but quiets down with a stern look from Lula.

“You can walk to school if you hate him so much.” Lula sucks her teeth and purses her lips. Maks, Lula’s boyfriend, drives us to school every day. He wears too much cologne, and I’m pretty sure his rock-solid hair is a soccer violation, but as long as he keeps saving goals, no one seems to mind.

Lula slams the Book on kitchen table and flips through the pages. I wonder what it’s like in other households during breakfast. Do their condiment shelves share space with jars of consecrated cemetery dirt and blue chicken feet? Do their mothers pray to ancient gods before they leave for work every morning? Do they keep the index finger bones of their ancestors in red velvet pouches to ward off thieves?

I already know the answer is no. This is my world. Sometimes I wish it weren’t.

Lula rinses the metal bowl I used to make the pancake batter and sets it beside the Book.

“Can I help?” Rose asks.

“It’s okay, Rosie,” Lula says. “We got this.”

Rose nods once but stays put to watch.

“Alex,” Lula says, “boil pink rose petals in water, and I’ll get started on the base.”

I do as I’m told even though I know my sister’s efforts are wasted. But that’s a secret I’m keeping to myself for now.