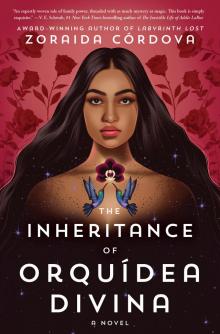

The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina

Zoraida Cordova

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

Para Ruth Alejandrina Guerrero Gordillo

Yo quiero luz de luna

para mi noche triste,

para sentir divina

la ilusión que me trajiste,

para sentirte mía, mía tú

como ninguna,

pues desde que te fuiste

no he tenido luz de luna.

—FROM “LUZ DE LUNA” BY ÁLVARO CARRILLO

Part I

INVITATION TO WITNESS A DEATH

0

THE INVITATION

You are invited to my home on May 14, the Year of the Hummingbird. Please begin to arrive no earlier than 1:04 p.m., as I have many matters to settle before the event. The stars have shifted. The earth has turned. The time is here. I am dying. Come and collect your inheritance.

Eternally,

Orquídea Divina Montoya

1

THE WOMAN AND THE HOUSE THAT HAD NEVER BEEN

For many mornings, there had been nothing but barren land. Then one day, there was a house, a woman, her husband, and a rooster. The Montoyas arrived in the town of Four Rivers in the middle of the night without fanfare or welcome wagons or cheesy, limp green bean dishes or flaky apple pies offered in an attempt to get to know the new neighbors. Though in truth, before their arrival, the townspeople had stopped paying much attention to who came and went anymore.

Finding Four Rivers on a map was nearly impossible, as the roads were still mostly gravel, and the memory of the place lived only in the minds of those who remained on purpose. Yes, there had been railroads once, great iron veins hammered into the rocky ground connecting the dusty heart of a country with an identity that changed depending on where lines were drawn.

If a traveler took a wrong turn on a highway, they used the Four Rivers gas station and old diner. When any visitor asked what four rivers intersected to give the town its name, the locals would scratch their heads and say something like, “Why, all the rivers have been dried out since 1892.”

Other than Garret’s Pump Station and the Sunshine diner—offering bottomless coffee for $1.25—Four Rivers could claim a population of 748 people, a farmer’s market, a stationery store, the world’s eighth largest meteor hole, the site of a mass dinosaur grave (which was debunked by furious paleontologists who had nothing nice to say in their journal about the prank pulled by the graduating class of ’87), the only video rental store for miles, Four Rivers High School (winners of the 1977 regional football championship), and the smallest post office in the country, which was the only thing preventing them from becoming a ghost town.

Four Rivers was special for reasons the living population had all but forgotten. It was, in the most general sense, magic-adjacent. There are locations all over the world where power is so concentrated that it becomes the meeting ground for good and evil. Call them nexuses. Call them lay lines. Call them Eden. Over the centuries, as Four Rivers lost its water sources, its magic faded, too, leaving only a weak pulse beneath its dry mountains and plains.

That pulse was enough.

In the dip of the valley where the four rivers had once intersected, Orquídea Montoya built her house in 1960.

“Built” was a bit of a stretch since the house appeared as if from the ether. No one was there when the skeletal foundation was laid or the shutters were screwed in, and not a single local could remember having seen tractors and bulldozers or construction workers. But there it was. Five bedrooms, an open living room with a fireplace, two and a half bathrooms, a kitchen with well-loved appliances, and a wraparound porch with a little swing where Orquídea could watch the land around her change. The most ordinary part of that house was the attic, which only contained the things the Montoyas no longer had use for—and Orquídea’s troubles. The entire place would become the thing of nightmares and ghost stories for the people who drove to the top of the hill, on the only road in or out, and stopped, watching and waiting for a peek at the strange family living within.

Once they realized they had a new permanent neighbor, the people of Four Rivers decided to start paying attention again to who came and went.

Who exactly were these Montoyas? Where did they come from? Why don’t they come to mass? And who, in God’s grasshopper-green earth, painted their shutters such a dark color?

Orquídea’s favorite color was the blue of twilight—just light enough that the sky no longer appeared black, but before pinks and purples bled into it. She thought that color captured the moment the world held its breath, and she’d been holding hers for a long time. That was the blue that accented the shutters and the large front door. A few months after her arrival, on her first venture into town to buy a car, she learned that all the ranch-style houses were painted in tame, watery pastels.

Nothing about Orquídea’s house was accidental. She’d dreamt of a place of her very own since she’d been a little girl, and when she’d finally acquired it, the most important things were the colors and the protections. For someone like Orquídea Divina Montoya, who had attained everything through stubborn will and a bit of thievery, it was not just important to protect it, but to hold on to it. That is why every windowpane and every door had a gold laurel leaf pressed seamlessly into the surface. Not just to keep the magic in, but to keep danger out.

Orquídea had carried her house with her for so long—in her heart, in her pockets, in her suitcase, and when it couldn’t fit, in her thoughts. She carried that house in the search for a place with a pulse of magic to anchor it.

In total, Orquídea and her second husband had journeyed for 4,898 miles, give or take a few. Some by carriage, some by ship, some by rail, and the last twenty solidly on foot. By the time she was done traveling, the wanderlust in her veins had dried up. Eventually she’d have children and grandchildren, and she’d see the rest of the world on the glossy postcards that covered the entire refrigerator. Like some, for her one pilgrimage was enough. She didn’t need to measure her worth by collecting passport stamps and learning half a dozen languages. Those were dreams for a girl left behind, one who had seen the pitch-black of the seamless sea and who had once stood at the center of the world. She’d lived a hundred lives in different ways, but no one—not her five husbands or her descendants—really knew her. Not in the way you can know someone, down to their bones, down to the secrets that can only be augured in bloody guts.

What was there to know?

Five foot one. Brown skin. Black hair. Blackest eyes. Orquídea Montoya was untethered to the world by fate. The two most important moments of her life had been predetermined by the stars. First, her birth. And second, the day she stole her fortune.

Her birthplace was a small neighborhood in the coastal city of Guayaquil, Ecuador. People think they know about misfortune and bad luck. But there was being unlucky—like when you tripped over your shoelaces or dropped a five-dollar bill in the subway or ran into your ex when you were wearing three-day-old sweatpants—then there was the kind of bad luck that Orquídea had. Bad luck woven into the birthmarks that dotted her shoulders and chest like constellations. Bad luck that felt like the petty vengeance of a long-forgotten god. Her mother, Isabela Montoya, had blamed her sin first and the stars second. The latter was true in more ways than one.

* * *

Orquídea was born during a time when the planets converged to create the singularly worst luck a person could ask for, a cosmic debt that was not her fault, and yet fate was coming to collect like a bookie. It was May 14, three minutes to midnight, when Orquídea chose to kick herself out of the womb before getting stuck halfway, as if she knew the world was not a safe place. Every nurse and doctor on shift rushed to help the lonely, young mother. At 12:02 a.m. on May 15, the baby was finally yanked out, half dead, with her umbilical cord wrapped around her little neck. The old nurse on shift remarked how the poor girl would lead an indecisive life—a foot here and the other there. Half present and half gone. Unfinished.

When she left Ecuador for good, she learned how to leave pieces of herself behind. Pieces that her descendants would one day try to collect to put her back together.

It took twenty years and two husbands, but Orquídea Divina made it to the United States. Despite having been born on a cosmic convergence of bad luck, Orquídea had discovered a loophole. But that’s to come later in her story.

This is about the woman and the house that had never been—until one day, they were undeniably there.

* * *

On their first morning in Four Rivers, Orquídea and her husband opened all the windows and doors. The house had been enchanted to anticipate all of their needs and provided them with the basics to get them started: bags of seeds, rice, flour, and salt, and a barrel of olive oil.

They’d need to plant right away. However, the ground surrounding the property was cracked, solid rock. Some locals said the fissures in the ground were so deep, you could drop a penny straight to hell. No matter how much it rained in Four Rivers, it was like the clouds purposely neglected the valley where their house now stood. But that didn’t matter. Orquídea was used to making something out of nothing. That was part of her bargain, her power.

The first thing she did was cover the floors in sea salt. She poured it between the floorboards, into the natural grooves and whorls in the wood. She crushed thyme, rosemary, rosehips, and dried lemon peels, scattering them into the mix. Then she swept it all out the front and back doors. It was magic she’d learned on her travels—a way to purify. She used the oil to restore the shine of the wood floors, and then to make the first breakfast she and her husband would have in their new home—fried eggs. She sprinkled fat crystals of salt over them, too, cooking the white edges until perfectly crisp, the yolks so bright they looked like twin suns. She could savor the promise of what was to come.

Decades later, before the end of her days, she would recall the taste of those eggs as if she’d just finished eating them.

* * *

The house at Four Rivers saw the birth of each one of Orquídea’s six children and five grandchildren—as well as the death of four husbands and one daughter. It was her protection from a world she didn’t know how to be a part of.

Once—and only once—did the neighbors arrive with shotguns and pitchforks trying to scare away the witch who lived in the center of the valley. After all, only magic could explain what Orquídea Divina Montoya had created.

Within their first month there, the dry bedrock had sprouted spindly grass. They grew in prepubescent patches at first, and then blanketed the earth. Orquídea had walked every inch of her property, singing and talking, sprinkling seeds, coaxing and daring them to take root. Then, the hills around them softened with wildflowers. The rain returned. It rained for days and then weeks, and when it stopped, there was a small lake behind the house. Animals returned to the area, too. Frogs leaped across mossy rocks and lily pads floating across the surface. Iridescent larvae hatched thousands of fish. Even deer wandered down from the hills to see what all the fuss was about.

Of course, the shotguns and pitchforks didn’t work. The mob barely got halfway down the hill before the land reacted. Mosquitoes swarmed, ravens circled overhead, the grass grew tiny thorns that drew blood. Discouraged, they turned around and went instead to the sheriff. He would run the witch out of their small town.

Sheriff David Palladino was the first Four Rivers local to introduce himself intentionally to Orquídea. And though they would go on to have an amiable relationship, which consisted of his keeping her grounds clear of nosy neighbors and her providing a daily hair-restoring tonic, there was a brief moment during their first encounter when Orquídea feared that, though she’d done everything right, she would have to go away.

Back then, Sheriff Palladino was twenty-three and on his first year of the job. He still had peach fuzz on his upper lip that wouldn’t grow and a full head of hair that made up for his too-wide nostrils, which let you see the tunnels of his nasal passages. His bright blue eyes gave him the effect of an owl, not wise but scared, which wasn’t good for the job. He’d never made a collar, because in Four Rivers there was no crime. The only murder on record would happen in 1965, when a truck driver would be found gutted on the side of the road. The killer was never caught. Even the fifty-year feud between the Roscoes and Davidsons was resolved just before he took up the seat of Sheriff. If the last Sheriff hadn’t died of an aneurysm on his desk at the age of eighty-seven, Palladino might still be a deputy.

After days of pressure from the townsfolk to find out about the newcomers (Who were these people? Where were their land deeds, their papers, their passports?), Palladino drove down the single dusty road that led to the strange house in the valley. When he arrived, he could hardly believe what he was looking at.

As a kid, he’d ridden bikes with his friends, shredding their shins on the bare rocks. Now, he inhaled the dark, freshly turned earth and grass. If he closed his eyes, he’d think he was far away from Four Rivers, and in some verdant, distant grove. But when he opened them, he was inarguably in front of the house owned by Orquídea Divina Montoya. He lifted his wide-brimmed hat to scratch his wheat-blond hair, matted at the temples in worm-like curls. As he rapped his knuckles against the door, he noticed the way the laurel leaves on the wood shimmered.

Orquídea answered, lingering at the threshold. She was younger than he’d expected, perhaps twenty years old. But there was something about her nearly black eyes that spoke of knowing too much too soon.

“Hi, ma’am,” he said, then stumbled on his clumsy tongue. “Miss. I’m Sheriff Palladino. There’s been some coyote sightings around the area, killing off livestock, and even poor Mrs. Livingston’s purebred hypoallergenic poodle. Just wanted to swing by and introduce myself and make sure y’all are all right.”

“No coyotes that we’ve seen,” Orquídea said in a crisp, regionless English. “I thought you might be here about the mob that tried to visit me a week ago.”

He blushed and lowered his head in shame at being caught lying. Although the story about coyotes was mostly true. Among the complaints he’d received was that the new Mexican family were witches who used coyotes as familiars. Another call had said that the dried-up valley no one ever went to except for vagrants and vagabond youths looking to skip school was being changed and they couldn’t have that. Four Rivers didn’t change. Palladino couldn’t understand why anyone would be opposed to change that looked like this—fresh and strong and vibrant. Life where there was nothing before. It was a goddamn miracle, but he had to do his duty by the townspeople he was sworn to protect. Which brought him to the next complaint. Illegals, a woman had whispered on the phone before hanging up. The family in the valley had shown up in the middle of the night, after all. Land was not supposed to be free. It had to be owned by someone—a person or the government. How had it gone for so long without being claimed?

“Would you like some coffee?” Orquídea asked with a smile that left him a little dizzy.

He’d been raised to never refuse a kind, neighborly gesture, and so he accepted. Palladino tipped his hat, then cradled it against his chest as he entered the house. “Thank you, miss.”

“Orquídea Divina Montoya,” she said. “But you can call me Orquídea just fine.”

&nb

sp; “I studied Spanish at the community college. That means ‘orchid’ right?”

“Very good, Sheriff.”

She stepped aside. A young woman about half his height, yet somehow, she felt as tall as the wooden beams above. She looked at his feet, watching carefully as he stepped over the threshold. He couldn’t have been sure, but it looked like she was waiting to see, not if he would enter, but if he physically could. Her shoulders relaxed, but her dark eyes remained wary.

As tall as he was, he felt himself shrink to put her at ease. Even left his gun in his glove compartment.

For the most part, David Palladino was like every other citizen of Four Rivers who’d never left. He didn’t need to be anywhere else, didn’t want to go. Before he found his purpose as a police officer, most days he was happy to get out of bed and get through the day. He believed in the goodness of people and that his grandmother’s soup could cure just about any injury. But magic? The kind that people were accusing Orquídea of? He chalked it up to old folks with dregs of lost myths stuck under their tongues. Magic was for the nickel machines at the summer carnival.

But he couldn’t deny that when he entered Orquídea’s home, he felt something, though he couldn’t truly name the exact sensation. Comfort? Warmth? As she led him through a hall filled with family portraits, he ignored the feeling. The wallpaper had been sun-kissed and the floors, though shining and smelling of lemon rind, were scuffed. There was an altar on a table in the foyer. Dozens of candles were melting, some faster than others, as if racing to get to the bottom of the wick. Bowls of fruit and coffee beans and salt were front and center. He knew some of the folks from the Mexican community nearby had similar reliquaries and statuettes of the Virgin Mary and half a dozen saints he couldn’t name. He sat through every Sunday mass, but he’d stopped listening a long time ago. His grandmother had been Catholic. His memory of her had faded but, standing in the Montoya house, thoughts of her slammed into him. He remembered a woman nearly doubled over with age, but still strong enough to roll a pin across the table to make fresh pasta on Sundays. He hadn’t thought of her in nearly fifteen years. The scent of rosemary that clung to her salt white hair, and the way she wagged her finger at him and said, “Be careful, my David, be careful of this world.” Ramblings of an old woman, but she was more than that. She’d watched him while his mother was sick and his father was breaking his bones at the mill. She’d prayed for his soul and his health, and he’d loved her infinitely for so long. So why didn’t he think of her anymore?