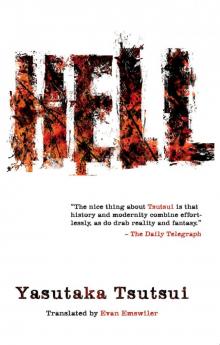

Hell

Yasutaka Tsutsui

ALMA BOOKS LTD

London House

243–253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almabooks.com

First published by Alma Books Ltd in 2007

This paperback edition first published in 2008

Original title: Heru (Hell)

Copyright © Yasutaka Tsutsui, 2003

Originally published in Japan by Bungei Shunju Ltd. Tokyo.

English translation © Evan Emswiler 2007

All rights reserved.

This book has been selected by the Japanese Literature Publishing Project (JLPP), which is run by the Japanese Literature Publishing and Promotion Center (J-Lit Center) on behalf of the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan.

Yasutaka Tsutsui and Evan Emswiler assert their moral right to be identified as the author and translator of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Cox & Wyman Ltd

ISBN-13: 978-1-84688-046-9

eISBN: 978-1-84688-255-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

HELL

It was late in the afternoon, and Nobuteru was rough-housing with two friends up on the school-yard platform used by the teachers to address the student body. It was five feet above the ground and a bad fall could have been dangerous, but this was far from their minds. Boys their age are confident that they’ll never be the ones to get hurt. Besides, it wasn’t the first time they played this game, and falling had always meant nothing more than cuts and bruises. They were covered in sweat and dirt and dressed in little more than rags, since new clothes could only be bought with war-ration coupons. They must have smelt awful, but they didn’t notice; boys in the fourth year of primary school never think about hygiene. Their only concern was knocking each other off the platform.

Yuzo, the biggest and most boisterous of the three, laughed loudly, revealing missing front teeth. He wiped his nose, smearing a slimy trail of snot onto his palm, which he stuck in Nobuteru’s face. Nobuteru screeched and leapt back – crashing into Takeshi behind him. Takeshi lost his footing and went tumbling off the platform. He landed on the ground awkwardly, body askew, and immediately began to wail. He was hollering something about his leg. From the way Takeshi was moaning, Nobuteru should have known this was no ordinary injury, but this realization would only come to him much later and with a great deal of guilt as he replayed the moment in his mind. Instead, Yuzo and Nobuteru exchanged embarrassed grins, jumped to the ground, and grabbed Takeshi’s left ankle. They began to pull him around by his oddly bent leg, singing, “Don’t cry, my little dove! You’ll always be my one true love!” They were trying to stop his tears by making him laugh.

But Takeshi’s leg was broken. His cries grew louder and soon the teachers came running. He was quickly loaded onto a stretcher and driven to the hospital in the small truck that delivered the school lunches.

When he finally returned to school, he was on crutches, and the leg never mended completely. From that point on, Nobuteru couldn’t bring himself to talk to Takeshi or even look him in his timid face.

But wait, there was something strange about this. They couldn’t possibly have sung ‘Don’t Cry, My Little Dove’. The song didn’t exist until after the war. Could Nobuteru have added this detail later in life? Still, he couldn’t for the life of him think what other song they might have sung that day.

Not long after this incident, just before he became a fifth-year student at school, Nobuteru and his family moved to Sasayama in Hyogo Prefecture. Students without relatives in rural areas were evacuated as a group soon after, but Nobuteru had no idea what happened to Yuzo or Takeshi. When the war was over, Nobuteru and his family returned to the city. Their house had escaped damage, but the houses of most of his friends were levelled in the air raids. Neither Takeshi nor Yuzo ever returned to school.

“Motoyama’s a yakuza now, you know.”

Nobuteru had just entered college when a classmate from primary school told him this. It wasn’t much of a surprise that Yuzo, with his bad grades and wild disposition, would become a gangster. But Nobuteru had fond memories of the times they spent together (with the exception of the accident that crippled Takeshi), and he had even come to think of Yuzo, the boy with missing front teeth, as his best childhood friend.

Nobuteru was seventy years old. He had done many bad and foolish things in his life; he was probably no better than Yuzo in that respect. For a while his pursuits had even skirted the underworld that Yuzo inhabited, and he had often mused about being reunited with his old friend one day. But at his primary-school reunion just after he had turned fifty, he learnt that Yuzo was killed in a gang fight while in his twenties. Nobuteru was shocked. All this time he had been reminiscing about a friend who had been dead for decades. How could Yuzo be dead while Nobuteru still lived?

Nobuteru himself had come close to death many times, although not in any way similar to the way Yuzo died. And at his advanced age, Nobuteru had another brush with death – in a way that seemed the domain of Japan’s elderly. Alone at home on New Year’s Day, he decided to add a mochi rice cake to the leftover soup. He remembered growing up hungry when food was scarce, and he loved the mochi that he had been deprived of as a child. He was slurping the soup like a greedy monkey, savouring every last bit of flavour, when the gooey mass of mochi got lodged in his throat. Suddenly he couldn’t breathe. He poked a finger in his mouth to hook the mochi out, but succeeded only in poking it further down his throat. He fell to the floor, gasping, his mind growing dim. He was reaching the point of no return. But he’d be a laughing stock, dying like this! Finally, he yanked out his dentures. The mochi stuck to the false teeth and slithered back up his throat as he pulled them out of his mouth.

How many times had he managed to cheat death? And how many more times would he do so before the end finally came? If he were younger, he might have rejoiced at having survived, but age had changed him. He was tired. Now something as insignificant as the way young people spoke was enough to set him off. He hated how they would say they “could care less” when they meant that they “couldn’t care less”. “You got a mobile, man?” they would say. What was that supposed to mean? But as a boy, Nobuteru’s conversations with Yuzo had been peppered with slang like “nif-tee” and “slick”, and as a college student he was known to refer to more than one girl as a “fox”.

Yuzo died after entering an enemy gang’s territory with two subordinates in tow. He was courageous almost to the point of foolishness, but he had no idea that he was walking to his death, and neither did Daté, who was right behind him. Daté was nineteen and in awe of Yuzo.

It was eight o’clock on an autumn night. Daté was walking cockily with his shoulders thrust back, just like Yuzo. He and Hattori, another protégé of Yuzo’s, walked together behind Yuzo through a back alley of the Misugi shopping arcade – a red-light district of bars, tiny restaurants, yakiniku barbecue joints and establishments of questionable repute. It was the Ikaruga gang’s territory, and that meant trouble for members of any other gang, but Daté

had no fear of death. Yuzo seemed invincible to him, and as long as Daté was with Yuzo, death held no sway over him.

Yuzo turned back at Daté and grinned. “Hey, Weasel. You’re not gunnin’ for my job, are you?” Weasel was Daté’s nickname.

“Who, me? I’m just a weasel.” It was one of Daté’s running jokes.

Hattori smiled at the two of them.

The camaraderie of the three men came to an abrupt end moments later when Yuzo was stabbed in the gut. Four members of the Ikaruga gang appeared, surrounding Yuzo, and after a brief shouting match they attacked him. But it was hardly a gang fight, as Nobuteru’s classmate had called it. The men who killed Yuzo didn’t even know that he belonged to the Sakaki gang. Yuzo fell to the ground as if bowing down before his attackers, and Daté’s illusions crumbled with him. How could Yuzo be killed so easily?

Daté and Hattori had been walking a bit behind Yuzo, and stopped in their tracks when the trouble started. The Ikaruga gangsters didn’t even realize that the three men were together. But then Hattori turned and ran, drawing their attention towards him. Daté also turned and made a haphazard dash for the main shopping strip, pushing people out of his way. He felt like he had walked out onto the balcony of a high-rise apartment only to find that he had stepped out of a window instead.

Hattori had turned right onto the main street, so Daté turned left. He was grateful that fear hadn’t rooted him to the spot; at least he was running. He ran and ran, giving silent thanks with every step. But he felt his knees grow weak as he heard the footsteps of his pursuers behind him.

“They’re gonna kill me,” he said to himself matter-of-factly. “I’m gonna die.”

He turned again into a back alley, nearly getting tripped up by a plastic bucket before colliding with someone. He felt like he was already dead. His stomach felt pumped full of air and about to pop out of his throat. His guts were churning.

He stumbled into a narrow alley lined with the back entrances to shops. If he wasn’t careful, he’d get trapped. He ran into another side street, panting, a desperate wheeze leaking from the back of his throat. Could that dark figure ahead be one of the gangsters? He doubled back, but no matter how far he ran, he never came out onto a main road. It was one back alley and narrow side street after another. It was just a matter of time before they got to him and put an end to his short life. If only he could go home and crawl into bed!

Daté pissed his pants as he ran. The warmth of his urine excited him, and at the same time it heightened his fear. He began to tremble. Death was close. Something approaching adoration came over his face as the surprisingly sweet scent of death filled his nostrils. And still he kept running, and running, and running.

Thinking about Takeshi always left Nobuteru consumed with guilt, and so he did his best to avoid it. When he heard that Takeshi had graduated with honours from a prestigious university and was working his way up the ranks of a large corporation, he felt an odd mixture of pain and relief, but he couldn’t shake a certain uneasiness. Even in his success, Takeshi could not have forgotten what Yuzo and he had done to him. Takeshi and Nobuteru lived in different worlds, so there was little chance that the two of them would ever meet, and it was even less likely that Takeshi would seek revenge against his old friends. But this did little to comfort Nobuteru. His uneasiness went deeper; it was connected to the fact that he was alive at all.

Some time between Nobuteru’s fifty-seventh birthday and the time he nearly choked to death at age seventy, Takeshi found himself sitting in a gloomy bar that seemed to be steeped in dust. He was dead. Unbeknown to Nobuteru, he had been killed in an automobile accident at age fifty-seven. He was no longer crippled; when he assumed his immortal form, his broken body and ruptured organs had been restored. The others he met there, unsure even of their own existence, called the place “Hell”. But Takeshi wasn’t disturbed about being there. He remembered what a familiar-looking man told him when he arrived:

“You know what Hell is? It’s just a place without God. The Japanese don’t believe in God to begin with, so what’s the difference between this world and the world of the living?”

“I suppose you’re right,” said Takeshi, without giving the matter much thought.

There were several ghostly figures sitting at tables in the bar, but Takeshi had little interest in them. He seemed to know some of them, but others he didn’t recognize at all. People would occasionally stop by to talk, and he got the feeling that he had met everyone in the bar at least once in life, but he wasn’t sure.

“Did everyone arrive here recently?” he asked a shabby-looking man, who also seemed familiar.

“No,” said the man. “I once met a man who had been here three hundred years. He was the chief retainer of a feudal lord in the late Edo period. People like him are so filled with regret that they’ll never get out of here.”

“What kind of regret?”

“His master died at the age of six. Just before he died, his master said the word he. The man thought it was a command to follow the boy into death, and he pleaded with his feudal lord for permission to kill himself. He was refused, but he committed hara-kiri anyway. When he got here and spoke to his young master, he discovered the boy hadn’t said he at all. He had said chi – his favourite maid was named Chié. The old guy still hasn’t recovered. He just wanders around saying, ‘I had so many things I wanted to do.’ People usually stop caring about that kind of thing once they get here, but not him.”

Takeshi realized that not everyone in Hell was connected to him after all. He was also surprised to hear that a six-year-old child was there.

“What’s your name? Haven’t we met somewhere before?” he asked the man, who had been eyeing Takeshi’s well-cut business suit.

“Could be. I was a businessman myself. Before I became homeless, that is. My name’s Sasaki.”

Sasaki, it turned out, had worked for a client of Shinwa Industries – Takeshi’s company. Takeshi was taken aback by this coincidence, but decided not to mention that he had been on the board of directors, since he might have been indirectly responsible for the man losing his job. In fact, Sasaki had met Takeshi once in life, but Sasaki didn’t recognize Takeshi without his crutches.

When Yoshitomo Izumi entered the bar, he was startled to see his old boss sitting alone in the middle of the room. While the other figures in the room were nothing but indistinct silhouettes, the figure of Takeshi Uchida was clear as day. What was he doing here? Takeshi had been a good boss, promoting Izumi often and always treating him well. Why was he in Hell?

Izumi walked up to Takeshi. “Hello, sir,” he said. “It’s me, Izumi.”

Takeshi had a talent for laughing loudly and genuinely, even at things that weren’t funny. And now, reunited with his subordinate, he laughed the same way he always had when he entertained clients. The situation wasn’t without an element of humour; the look on Izumi’s face, a mixture of trust and diffidence, was exactly the same as it had been at the office.

“A plane crash, was it? Well, have a seat.”

In Hell it was possible to view moments in another person’s life simply by staring at them. There were no comic-book-style balloons above their head to indicate what they were thinking, nor was it a form of mental telepathy. Instead, the truth was revealed through a kind of vision that crept up from the back of one’s mind. So as he sat down, Izumi was astonished to see that Takeshi had had an affair with his wife. He saw everything that had taken place, through Takeshi’s eyes, through the eyes of his wife Sachiko and through his own eyes as well.

Takeshi could tell from the expression on Izumi’s face that he now knew everything, but Takeshi didn’t go on the defensive. He merely nodded calmly.

“So you know,” he said.

“Sir…”

Seeing Takeshi without his crutches, Izumi understood that he was looking at Takeshi’s immortal form. And although Izumi’s own body had been horribly mangled and charred in a plane crash, the fact that he now sat the

re intact and apparently immortal made it painfully obvious where they both were. Perhaps that was why he felt no anger or hatred towards his boss, and why no feelings of jealousy welled up in his heart. When he thought about it, he hadn’t really loved Sachiko anyway. And hadn’t he himself betrayed her? But beyond that, Izumi now also realized that his unusually rapid advancement at the company – where he became head of general affairs at the age of forty – had been due largely to Takeshi’s support. Sachiko had only agreed to Takeshi’s overtures on the condition that he help her husband’s career.

In his vision, Izumi had seen Takeshi and his beautiful wife meet at an office party. He saw Sachiko’s compassion for the disabled man and her attraction to his refined bearing. He saw the two of them walking in a hotel garden on a Friday evening. And he saw Sachiko and Takeshi as they made love. Everything was revealed to him in minute detail, down to the smell that filled the hotel room. It was the stifling body-heat smell created when a man and a woman come together, bare skin against bare skin. It is a smell no movie or tawdry romance novel can duplicate. And somehow it seems even more pungent when you aren’t a part of it.

Although he appreciated Sachiko’s beauty in a detached way, Izumi no longer felt any physical attraction to her. This was something that happened to husbands and wives after a while, he thought, and he saw nothing wrong with his obsession with someone else. The other woman was the actress Yumiko Hanawa. Every Wednesday night, Izumi had gone to the Night Walker, a club that Yumiko frequented after hosting her Wednesday-night television variety show. Sometimes she would come close to Izumi’s table as she moved like a breeze over the dance floor. Sometimes she and her friends would take seats close to his. And sometimes he would catch a whiff of her perfume or intercept one of her seductive glances. The chance for such a thrill once a week had been enough to fulfil him.

Takeshi found it odd that Izumi’s attitude towards him remained unchanged, despite the fact that he had seen the truth of his affair. But maybe that was all part of being in Hell. There didn’t seem to be any point in getting angry. Why get jealous? True, Takeshi had been unemotional in life, but had Izumi also been this detached? Takeshi felt a strange closeness to the stolid Izumi next to him.