Devil's Dice

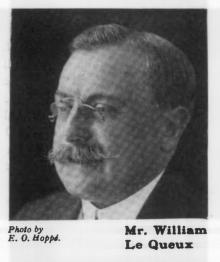

William Le Queux

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Devil's DiceBy William Le QueuxPublished by Rand, McNally and Company, Chicago and New York.This edition dated 1897.

Devil's Dice, by William Le Queux.

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________DEVIL'S DICE, BY WILLIAM LE QUEUX.

CHAPTER ONE.

QUEEN OF THE UNKNOWN.

Let me gaze down the vista of the tristful past.

Ah! there are things that cannot be uttered; there are scenes that stillentrance me, and incidents so unexpected and terrible that they cause meeven now to hold my breath in horror.

The prologue of this extraordinary drama of London life was enactedthree years ago; its astounding denouement occurred quite recently.During those three weary, anxious years the days have glided on as theyglide even with those who suffer most, but alas! I have the sense ofhaving trodden a veritable Via Dolorosa during a century, the tragedy ofmy life, with its ever-present sorrow, pressing heavily upon meperpetually. Yet my life's journey has not always been along the barrenshore of the sea of Despair. During brief moments, when, with the sweetchildlike angel of my solitude, heaven and earth have seemed to glideslowly into space, I have found peace in the supreme joy of happiness.My gaze has been lost in the azure immensity of a woman's eyes.

In this strange story, this astounding record of chastity of affectionand bitter hatred, of vile scheming, of secret sins and astoundingfacts, I, Stuart Ridgeway, younger son of Sir Francis Ridgeway, Memberfor Barmouth and banker of the City of London, am compelled to speak ofmyself. It is indeed a relief to be able to reason out one'smisfortunes; confession is the lancet-stroke that empties the abscess.The Devil has thrown his dice and the game is up. I can now lay barethe secret of my sorrow.

Away south in the heart of the snow-capped Pyrenees, while idling away afew sunny weeks at Bagneres-de-Luchon, that quaint little spa so popularwith the Cleopatras of the Boulevards, nestling in its secluded valleybeneath the three great peaks of Sacrous, de Sauvegarde, and de la Mine,a woman first brought sweetness to the sadness of my melancholy days.Mine was an aimless, idle life. I had left behind me at college areputation for recklessness. I was an arrant dunce at figures, andfinance had no attraction for me. I had lived the semi-Bohemian life ofa law student in London, and grown tired of it I had tried art andignominiously failed, and, being in receipt of a generous allowance froman indulgent father, I found myself at the age of twenty-eight withoutprofession, a mere world-weary cosmopolitan, wandering from place toplace with the sole object of killing time.

Having taken up my quarters alone at the Hotel des Bains, that glaringbuilding with its dead-white facade in the Allee d'Etigny--themagnificent view from which renders it one of the finest thoroughfaresin the world--I soon became seized by ennui.

The place, filled with the _haut ton_ of Paris, was gay enough, butsomehow I met no one at the table d'hote or elsewhere whom I cared toaccept as companion. Sick of the utter loneliness amid all the madgaiety, I was contemplating moving to Biarritz, where a maiden auntresided, when one evening, while seated in the picturesque Casino Gardenlistening to the band, I saw in the crowd of chattering, laughingpromenaders a woman's face that entranced me. Only for a second in thefaint light shed by the Chinese lanterns, strung from tree to tree, wasI able to distinguish her features. In that brief moment, however, oureyes met, yet next second she was gone, lost in one of the gayest crowdsin Europe.

The next night and the next I sat at the same little tin table taking mycoffee and eagerly scanning the crowd passing and re-passing along thebroad gravelled walk until once again I saw her. Then, held infascination by her marvellous beauty, attracted as a needle by a magnet,I rose and followed her. Like myself she was alone, and a trivialaccident, of which I eagerly availed myself, gave me an opportunity ofintroducing myself. Judge my joyful satisfaction when I found that shewas English, although her dress and hat bore the unmistakable stamp ofthe Rue de la Paix, and her chic was that of the true Parisienne. As wewalked together in the shadows beyond the public promenade, she told methat her home was in London; that on account of her father having beencompelled to return suddenly, she had been left alone, and she admittedthat, like myself, she had become dull and lonely.

Apparently she had no objection to my companionship, although she stroveto preserve a British rigidity of manner and respect for theconvenances. Yet after the reserve of the first half-hour had worn offwe sat down together under a tree near the band-stand, and I gave her acard. She, however, refused to give me one.

"Call me Sybil," she said smiling.

"Sybil!" I repeated. "A name as charming as its owner. Is your nameSybil--only Sybil?"

"My surname is of no consequence," she answered quickly, with a slighthaughtiness. "We are merely English folk thrown together in this place.To-morrow, or the next day perhaps, we shall part, never to meetagain."

"I trust not," I said gallantly. "An acquaintanceship commenced underthese strange conditions is rather romantic, to say the least."

"Romantic," she repeated mechanically, in a strange tone. "Yes, that isso. Every one of us, from pauper to peer, all have our little romances.But romance, after all, is synonymous with unhappiness," and she drew along breath as if sad thoughts oppressed her.

A moment later, however, she was as gay and bright as before, and wechatted on pleasantly until suddenly she consulted the tiny watch in herbangle and announced that it was time she returned. At her side Iwalked to her hotel, the Bonnemaison, and left her at the entrance.

We met frequently after that, and one morning she accompanied me on adrive through the quaint old frontier village of St Aventin and onthrough the wild Oo Valley as far as the Cascade.

As in the bright sunshine she lounged back in the carriage, her fair,flawless complexion a trifle heightened by the pink of her parasol, Igazed upon her as one entranced. The half lights of the Casino Gardenhad not been deceptive. She was twenty-two at the most, and absolutelylovely; the most bewitching woman I had ever seen. From beneath amarvel of the milliner's art, tendrils of fair hair, soft as floss silk,strayed upon her white brow; her eyes were of that clear childlike bluethat presupposes an absolute purity of soul, and in her pointed chin wasa single dimple that deepened when she smiled. Hers was an adorableface, sweet, full of an exquisite beauty, and as she gazed upon me withher great eyes she seemed to read my heart. Her lithe, slim figure wasadmirably set off by her gown of soft material of palest green, whichhad all the shimmer of silk, yet moulded and defined its wearer like aSultan's scarf. It had tiny shaded stripes which imparted a deliciouseffect of myriad folds; the hem of the skirt, from under which a daintybronze shoe appeared, had a garniture in the chromatics, as it were, ofmingled rose and blue and green, and the slender waist, made long aswaists may be, was girdled narrow but distinctive.

As I sat beside her, her violet-pervaded chiffons touching me, theperfume they exhaled intoxicated me with its fragrance. She was anenchantress, a well-beloved, whose beautiful face I longed to smotherwith kisses each time I pressed her tiny well-gloved hand.

Her frank conversation was marked by an ingenuousness that was charming.It was apparent that she moved in an exclusive circle at home, and fromher allusions to notable people whom I knew in London, I was assuredthat her acquaintance with them was not feigned. Days passed--happy,idle, never-to-be-forgotten days. Nevertheless, try how I would, Icould not induce her to tell me her name, nor could I discover it at herhotel, for the one she had given there was evidently assumed.

"Call me Sybil," she always replied when I alluded to the subject.

"Why are you so determined to preserve the s

ecret of your identity?" Iasked, when, one evening after dinner, we were strolling beneath thetrees in the Allee.

A faint shadow of displeasure fell upon her brow, and turning to mequickly she answered:

"Because--well, because it is necessary." Then she added with a strangetouch of sadness, "When we part here we shall not meet again."

"No, don't say that," I protested; "I hope that in London we may seesomething of each other."

She sighed, and as we passed out into the bright moonbeams that floodedthe mountains and valleys, giving the snowy range the aspect of afar-off fairyland, I noticed that her habitual brightness had givenplace to an expression of mingled fear and sorrow. Some perpetualthought elevated her forehead and enlarged her eyes, and a little later,as we walked slowly forward into the now deserted promenade, I repeateda hope that our friendship would always remain sincere and unbroken.

"Why