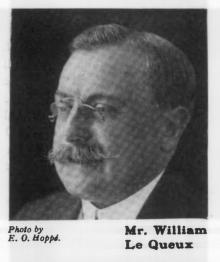

The Bomb-Makers

William Le Queux

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

The Bomb-MakersBeing some Curious Records concerning the Craft and Cunning of TheodoreDrost, an enemy alien in London, together with certain Revelationsregarding his daughter Ella.By William Le QueuxPublished by Jarrolds, London.

The Bombmakers, by William Le Queux.

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________THE BOMBMAKERS, BY WILLIAM LE QUEUX.

CHAPTER ONE.

THE DEVIL'S DICE.

"Do get rid of the girl! Can't you see that she's highly dangerous!"whispered the tall, rather overdressed man as he glanced furtivelyacross the small square shop set with little tables, dingy in the hazeof tobacco-smoke. It was an obscure, old-fashioned little restaurant inone of London's numerous byways--a resort of Germans, naturalised andotherwise, "the enemy in our midst," as the papers called them.

"I will. I quite agree. My girl may know just a little too much--if weare not very careful."

"Ah! she knows far too much already, Drost, thanks to your ridiculousindiscretions," growled the dark-eyed man beneath his breath. "Theywill land you before a military court-martial--if you are not careful!"

"Well, I hardly think so. I'm always most careful--most silent anddiscreet," and he grinned evilly.

"True, you are a good Prussian--that I know; but remember that Ella has,unfortunately for us, very many friends, and she may talk--women's talk,you know. We--you and I--are treading very thin ice. She is, Iconsider, far too friendly with that young fellow Kennedy. It'sdangerous--distinctly dangerous to us--and I really wonder that youallow it--you, a patriotic Prussian!"

And, drawing heavily at his strong cigar, he paused and examined itswhite ash.

"Allow it?" echoed the elder man. "How, in the name of Fate, can Iprevent it? Suggest some means to end their acquaintanceship, and I amonly too ready to hear it."

The man who spoke, the grey-haired Dutch pastor, father of Ella Drost,the smartly-dressed girl who was seated chatting and laughing merrilywith two rather ill-dressed men in the farther corner of the littlesmoke-dried place, grunted deeply. To the world of London he posed as aDutchman. He was a man with a curiously triangular face, a big squareforehead, with tight-drawn skin and scanty hair, and broad heavyfeatures which tapered down to a narrow chin that ended in a pointed,grey, and rather scraggy beard.

Theodore Drost was about fifty-five, a keen, active man whosecountenance, upon critical examination, would have been found to becuriously refined, intelligent, and well preserved. Yet he was shabbilydressed, his long black clerical coat shiny with wear, in contrast withthe way in which his daughter--in her fine furs and clothes of thelatest mode--was attired. But the father, in all grades of life, isusually shabby, while his daughter--whatever be her profession--lookssmart, be it the smartness of Walworth or that of Worth.

As his friend, Ernst Ortmann, had whispered those warning words he hadglanced across at her, and noting how gaily she was laughing with hertwo male friends, a cigarette between her pretty lips, he frowned.

Then he looked over to the man who had thus urged discretion.

The pair were seated at a table, upon which was a red-bordered cloth,whereon stood two half-emptied "bocks" of that light beer so dear to theTeuton palate. They called it "Danish beer," not to offend Englishcustomers.

The girl whose smiles they were watching was distinctly pretty. She wasabout twenty-two, with a sweet, eminently English-looking face, fair andquite in contrast with the decidedly foreign, beetle-browed features ofthe two leering loafers with whom she sat laughing.

Theodore Drost, to do him justice, was devoted to his daughter, who,because of her childish aptitude, had become a dancer on the lowestlevel of the variety stage, a touring company which visited fifth-ratetowns. Yet, owing to her discovered talent, she had at last graduatedthrough the hard school of the Lancashire "halls," to what is known asthe "syndicate halls" of London.

From a demure child-dancer at an obscure music-hall in the outersuburbs, she had become a noted revue artiste, a splendid dancer, whocommanded the services of her own press-agent, who in turn commandedhalf-a-dozen lines in most of the London morning papers, both herprestige and increased salary following in consequence. The Britishpublic so little suspect the insidious influence of the press-agent inthe formation of modern genius. The press-agent has, in the past, mademany a mediocre fool into a Birthday Baronet, or a "paid-for Knight,"and more than one has been employed in the service of a CabinetMinister. Oh what sheep we are, and how easily we are led astray!

On that wintry night, Ella Drost--known to the theatre-going public asStella Steele, the great revue artiste whose picture postcards wereeverywhere--sat in that stuffy, dingy little restaurant in Soho, sippinga glass of its pseudo-Danish lager, and laughing with the twounpresentable men before her.

Outside the unpretentious little place was written up the single word"Restaurant." Its proprietor a big, full-blooded, fair-bearded son ofthe Fatherland, had kept it for twenty years, and it had been theevening rendezvous of working-class Germans--waiters, bakers, clerks,coiffeurs, jewellers, and such-like.

Here one could still revel in Teuton delicacies, beer brewed in Hamburg,but declared to be "Danish," the succulent German liver sausage, thesausage of Frankfort--boiled in pairs of course--the palatablesauerkraut with the black sour bread of the Fatherland to match.

"I wish you could get rid of Kennedy," said Ortmann, as he again, inconfidence, bent across the table towards Ella's father. "I believeshe's in collusion with him."

"No," laughed the elder man, "I can't believe that. Ella is too good adaughter of the Fatherland." He was one of Germany's chief agents inEngland, and had much money in secret at his command.

Ortmann screwed up his eyes and pursed his lips. He was a shrewd,clever man, and very difficult to deceive.

"Money is at stake, my dear Drost," he whispered very slowly--"bigmoney. But there is love also. And I believe--nay, I'm sure--thatKennedy loves her."

"Bah! utterly ridiculous!" cried her father. "I don't believe that fora single moment. She's only fooling him, as she has fooled all theothers."

"All right. But I've watched. You have not," was the cold reply.

From time to time the attractive Ella, on her part, glanced across ather father, who was whispering with his overdressed companion, and, tothe keen observer, it would have been apparent that she was only smokingand gossiping with that pair of low-bred foreigners for distinctpurposes of her own.

The truth was that, with her woman's instinct, feminine cleverness andingenuity, she, being filled with the enthusiasm of affection for heraviator-lover, was playing a fiercely desperate part as a staunch andpatriotic daughter of Great Britain.

The hour was late. She had hurried from the theatre in a taxi, thecarmine still about her pretty lips, her eyes still darkened beneath,and the greasepaint only roughly rubbed off. The great gold and whitetheatre near Leicester Square, where, clad in transparencies, she was"leading lady" in that most popular revue "Half a Moment!" had beenpacked to suffocation, as indeed it was nightly. Officers and men homeon leave from the battle-front all made a point of seeing the pretty,sweet-faced Stella Steele, who danced with such artistic movement, andwho sang those catchy patriotic songs of hers, the stirring choruses ofwhich even reached the ears of the Bosches in their trenches. And inmany a British dug-out in Flanders there was hung a programme of therevue, or a picture postcard of the seductive Stella.

There were, perhaps, other Stella Steeles on the stage, for the namewas, after all, not an uncommon one, but this star of the whole Steelefamily had arisen from the theatrical firmament since the

war. She, thelaughing girl who, that night, sat in that obscure, smoke-laden littleden of aliens in Soho, was earning annually more than the "pooled"salary of a British Cabinet Minister.

That Stella was a born artiste all agreed--even her agent, that fatcigar-smoking Hebrew cynic who regarded all stage women as mere cattleout of whom he extracted commissions. To-day nobody can earn unusualemoluments in any profession without real merit assisted by a capableagent.

Stella Steele was believed by all to be thoroughly British. Nobody hadever suspected that her real name was Drost, nor that her bespectacledand pious father had been born in Stuttgart, and had afterwards becomenaturalised as a Dutchman before coming to England. Thecigarette-smoking male portion of the khaki-clad crowd who so loudlyapplauded her every night had no