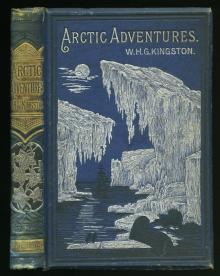

Arctic Adventures

William Henry Giles Kingston

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Arctic Adventures, by WHG Kingston.

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________ARCTIC ADVENTURES, BY WHG KINGSTON.

CHAPTER ONE.

I had often dreamed of icebergs and Polar bears, whales and rorquals, ofwalruses and seals, of Esquimaux, and Laplanders and kayaks, of theAurora Borealis and the midnight sun, and numerous other wonders of thearctic regions, and here was I on board the stout ship the _HardyNorseman_, of and from Dundee, Captain Hudson, Master, actually on myway to behold them, to engage in the adventures, and perchance to endurethe perils and hardships which voyagers in those northern seas must beprepared to encounter.

Born in the Highlands, and brought up by my uncle, the laird ofGlenlochy, a keen sportsman, I had been accustomed to roam over mynative hills, rifle in hand, often without shoes, the use of which Ilooked upon as effeminate. I feared neither the biting cold, nor theperils I expected to meet with. I had a motive also for undertaking thetrip. My brother Andrew had become surgeon of the _Hardy Norseman_ andwe were both anxious to obtain tidings of our second brother David, whohad gone in the same capacity on board the _Barentz_, which had sailedthe previous year on a whaling and sealing voyage to Spitzbergen andNova Zembla, and had not since been heard of. I was younger thaneither, and had not yet chosen my future profession; though, havingalways had a fancy for the sea, I was glad of an opportunity of judginghow near the reality approached my imaginings, besides the chief motivewhich had induced me to apply to our old friend Captain Hudson for leaveto accompany Andrew.

I had undertaken to make myself generally useful, to act as purser andcaptain's clerk, to assist in taking care of the ship when the boatswere away, and to help my brother when necessary, so that I wasgenerally known as the "doctor's mate."

The _Hardy Norseman's_ crew consisted of Scotchmen, Shetlanders, Orkneymen, Norwegians, and Danes. The most notable among them was SandySteggall, the boatswain, a bold harpooner, who possessed a tongue--thesecond mate used to say--as long as a whale spear, which he kept waggingday and night, and I got no little insight into the particulars of ourfuture life by listening to his yarns.

We had not been long at sea, when one night, it having fallen calm, Iwent forward, where I found the watch on deck assembled, Sandy and twoor three others holding forth in succession, though the boatswain, byvirtue of his rank, claimed the right of speaking the oftenest.Wonderful were Sandy's yarns. He told how once he had been surprised bya bear, when, as he was on the point of being carried off, he stuck hislong knife into bruin's heart, and the creature fell dead at his feet.On another occasion, when landing on the coast of Spitzbergen, he andhis companions found a hut with three dead men within, and others lyingin shallow graves, the former having buried the latter, and then diedthemselves, without a human soul near to close their eyes. Again, hehad come upon the grave of an old shipmate who had been dead twentyyears, whose features, frozen into marble, looked as fresh as when firstplaced there, the only change being that his hair and beard had grownmore than half a fathom in length.

Yarn after yarn of shipwreck and disaster was spun, until I began towish that David had not gone to sea, and that we could have avoided thenecessity of going to look for him.

With the bright sun-light of the next morning I had forgotten the moresombre hues of his narratives, and looked forward with as much eagernessas at first to the adventures we might meet with.

That afternoon I had occasion to go into the hold, accompanied by theboatswain and another man carrying a lantern, to search for some storeswhich ought to have been stowed aft, when, as I was looking about, Ifancied I heard a moan. I called the attention of the boatswain to it.We listened.

"Bring the light here, Jack!" he said to the seaman, and he made his wayin the direction whence the sound proceeded. Presently, as he stoopeddown, I heard him exclaim--

"Where do you come from, my lad?"

"From Dundee. I wanted to go to sea, so I got in here," answered theperson to whom he spoke, in a weak voice.

"Come out then and show yourself," said Sandy.

"But that's more than I can do!" was the answer.

"I'll help you then," returned the boatswain, dragging out a lad aboutmy own age, apparently so weak and cramped as to be utterly unable tohelp himself.

"We must carry you to the doctor, for we don't want to let you die,though you have no business to be here," observed Sandy, with a look ofcommiseration. He afterwards remarked to me, "I did the same thingmyself, and I couldna say anything hard to the puir laddie."

The boatswain at once carried the young stranger up on deck. Thecaptain had begun to rate him well for coming on board without leave,but seeing that he was ill fit to bear it, he told me to summon thedoctor, who was below.

I called Andrew, who returned with me to the deck.

"What's your name?" asked the captain, while Andrew was feeling hispulse.

"Ewen Muckilligan," was the answer.

As I heard the name, I looked more particularly than before at the youngstowaway's features, and recognised an old schoolfellow and chum ofmine. Both his parents being dead, he had been left under charge ofsome relatives who cared very little for him.

"He only requires some food to bring him round, but the sooner he has itthe better," observed Andrew.

With the captain's permission, I got him placed in my berth, where,after swallowing a basin of broth, he fell asleep. By frequentrepetition of the same remedy, he was able, after a couple of days, tostand on his feet, when the captain administered a severe lecture,telling him that he must send him back by the first vessel we might fallin with. Ewen, however, begged so hard to remain, that the captainpromised to consider the matter.

"I may as well make a virtue of necessity, for we are not at all likelyto fall in with any homeward-bound craft," he afterwards observed toAndrew.

Hearing this, I told Ewen that he might make his mind easy, that if hehad determined to be a sailor he had now an opportunity of learning hisprofession, though he would gain his experience in a very rough school.

As Ewen was in every sense a gentleman, he was allowed to mess with us;for which permission I was very grateful to Captain Hudson, as mostcaptains would have sent him forward to take his chance with the men.He soon proved that he intended to adhere to his resolution. On alloccasions he showed his willingness to do whatever he was set to, whilehe was as active and daring as any one on board.

We were forward one evening, talking to the men, after they had knockedoff work, the second mate having charge of the deck, the captain, firstmate, and Andrew being below, when it was suggested that we two shouldtry who could first reach the main truck. One was to start from thefore-top, the other from the mizen cross-trees. We were to come down ondeck and then ascend the main-mast. We cast lots. It was decided thatEwen should start from the fore-top, I from the latter position. Thesecond mate liked the fun, and did not interfere. We took up ourpositions, waiting for the signal--the wave of a boat-flag from thedeck. The moment I saw it, without waiting to ascertain what Ewen wasabout, I began to run down the mizen shrouds; he in the meantimedescended by the back stay and was already half up the main rigging onthe port side before I had my feet on the ratlines on the starboardside. When once there I made good play, but he kept ahead of me and hadalready reached the royal-mast, swarming up it, before I had got on thecross-trees. As he gained the truck he shouted "Won! won!"

I slid down, acknowledging myself defeated, and feeling not a littleexhausted by my exertions. Judging by my own sensations, I feared thathe might let go and be killed. I dared not, as I made my way d

own, lookup to see what he was doing. Scarcely had I put my foot on deck than hestood by my side, having descended by the back stay.

The crew applauded both of us, and Ewen was greatly raised in theirestimation when they found that he had never been before higher than themaintop.

Sandy Steggall, the boatswain, however, who soon afterwards came ondeck, scolded both of us for our folly, and rated the men well forencouraging us.

"What would ye have said if these twa laddies had broken their necks, orfallen overboard and been drowned?" he exclaimed.

We had, I should have said, four dogs on board, all powerful animals;two were Newfoundland dogs, one was a genuine Mount Saint Bernard, and afourth was a mongrel, a shaggy monster, brought by our captain fromNorway. They were known respectively as Bruno, Rob, Alp and Nap.

We had crossed the Arctic circle, sighted the coast of Norway; and, withthe crow's nest at the mast head,