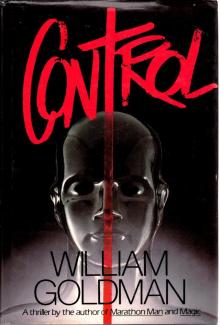

Control

William Goldman

William Goldman

Control

1982

FOR DAVID SHABER

…Many puzzling observations have turned up in medicine, psychology, and anthropology. In all these areas, effects have been reported that would seem possibly to be the result of some sort of psychic causation, although at this stage it is impossible, of course, to say what the explanation is.

J. B. RHINE, New World of the Mind

PART ONE

Victims

1

Edith

If there was one place in this world Edith never expected trouble, it was Bloomingdale’s.

For two reasons, one minor, one major. The minor reason was familiarity: Edith had shopped the store since childhood. The family duplex was at 65th and Park, so when her mother needed to buy her overalls or Mary Janes, logic dictated Bloomingdale’s.

Edith’s mother never much liked the place. And with good enough reason, since it’s difficult for people today to remember that not so long ago, the giant department store at 59th and Lex wasn’t much above Macy’s in quality, and certainly ranked far below Altman’s or Bergdorf s or Saks.

Mrs. Mazursky, a sweet tub, naturally could have afforded cabs anywhere she wanted, but something in her rebelled at the financial waste. She was wealthy now, very, but she had been born middle-class Brooklyn, and even though her body presently inhabited Manhattan’s Upper East Side, her soul would never budge from Flatbush Avenue.

By the time Edith was ten, she was allowed to go off to the store alone, on the proviso that she had been good the day before, which Edith generally managed to be only on days ending in y. So she would bathe carefully and don her best party dress and take a small purse and skip on over.

And spend, literally, hours. Riding the escalators, and lingering in the toy department, and staring at the foods from all over the world, and sitting in the furniture floor samples while imagining adventures that often involved her having to step in for Nancy Drew when Nancy was mysteriously taken ill, and studying the paintings on the walls in the decorator showrooms, carefully noting how the painting would have altered if she had been dealing with the canvas.

Country children often fantasize on hilltops or in treehouses; Edith’s magic place was Bloomingdale’s and it kept its hold on her while she grew. No better proof need be given than the simple recounting of the furor Edith caused when she was thirty-two and attending one of Sally Levinson’s very formal dinner parties.

Sally had been Edith’s roommate at Radcliffe, and was her dearest dearest friend. (She was also an anglophile of maddening proportions. A Chicago girl, her English accent would have shamed Alistair Cooke.) Upon graduation, with part of her inheritance, she opened an art gallery on 57th Street. She was aggressive and tasteful and willing to gamble on unknown talent, and soon she had one of the best galleries on 57th Street. Once that fact was established, Sally said “screw” to all the fancies and moved to the Village, and when that became too chic, to SoHo. Eventually she bought a building in TriBeCa before anyone could even spell it, and today people come from this country and abroad to see just what it is that Sally Levinson is up to now. Few things still give Sally more pleasure than standing by her windows and watching the rich, with that panicked look in their eyes—ye Gods, where are we?—moving along TriBeCa’s streets frantically trying to find the sanctuary of the Levinson Gallery.

Sally was born rich but she never thought much about it. She wasn’t sure if she’d been born a Lesbian or not, but she knew she was one. She hid it, of course, kept her hair long, wore lots jsf makeup, dated every weekend at Francis Parker in her teens. She was popular at Radcliffe, probably more than Edith, who became her roommate junior year. They had both wanted singles, the administration had erred, they decided what the hell, let’s try it and see.

By Christmas of that year, Sally was terribly, and as it turned out, permanently in love with Edith. Oh, not physically. She would have cut off her hand before it tried to touch.

It was just that if you were Sally, Sally the dyke from Chicago, if you had her demons inside you, dawn and night inside you, you had to love Edith Mazursky, she was just that tranquil, that decent, that nonjudgmental. Edith was simply, in other words, so fucking good.

By spring vacation, the time had come to decide on senior year roommates. Edith, one morning over coffee, suggested they continue on. Sally, of course thrilled, simply blew hard into her steaming cup and said that well, she’d have to think about it. Edith, certainly surprised, perhaps hurt, said that well, that was probably a wise thing to do.

Edith took her books and went off to classes. Sally cut her classes and lay alone on her bed, chain smoking. She had always suspected it would be hard the first time she told someone. She never guessed it would be immobilizing. It seemed fair to her that before she accepted Edith’s suggestion, Edith know her truth. But more than that, Edith was the first straight person Sally had met who she felt might not just not scorn her, but might even understand.

How to tell, though; how to tell?

That night, late, when Sally came in from ‘Having a few at the local” as she always put it, Edith was getting ready for sleep, face scrubbed, sitting on the edge of her bed, brushing her thick reddish hair. Sally suspected that if Edith had ego about anything, it was that, her hair; on an Irisher like Maureen O’Hara it was nice enough; on a Jewish girl from Manhattan it was gold.

Sally flopped in the overstuffed chair across the room. “Phillip again?” she asked. Edith had been seeing Phillip Holtzman for several months now and they were obviously in love.

Edith nodded, went on brushing her reddish hair. A hundred strokes, no matter what.

“Ya get in?” Sally wondered.

Edith didn’t honor the remark with a reply.

“Well how ‘bout bare tit?”

Edith gave Sally a look.

“That’s how men talk, isn’t it? I mean, tell me that’s not the way they go on about us? Gonna marry Phillip?”

Edith put her brush down, sat there in silence, just staring at her roommate. Waiting.

“Me, I wonder if I’ll ever marry,” Sally said finally. “Where is it fucking written that marriage is ice cream? Sure, if it’s kids you’re after, I wouldn’t want some bastard, that’s shitty to the kid, but maybe I’ll just”—and now the words came faster—”you wanna screw, you live with some guy, you’re bored, it’s on to the next, no papers, no contract—-or living alone, who’s to say that’s so terrible—you get horny, you hit your local, pick up some jerk, bring him back, let him plug away for a while, or maybe, or maybe if that’s not the answer, then—”

Suddenly from Edith now: “Shh.”

Sally quieted.

“I know.” And it was clear from her tone that she did know. Everything. And that she didn’t much care. Sally got out the vodka, poured herself a double. Edith went back to brushing her hair …

So they roomed together senior year, becoming like sisters,

spatting like sisters too, often about Sally’s anger that Edith pissed

away her talent, because it was evident to Sally even then that

Edith had the hands and the eye, that Edith could paint. Though

she rarely did.r

On graduation, Edith married Phillip and Sally got terribly angry that Edith was so hidebound by tradition that she wouldn’t let Sally be best man at the ceremony.

And when Edith got quickly and happily pregnant Sally went to England where she studied art for two years and came back with that accent that only Edith was allowed to tease her about. And she opened her gallery and began giving parties at her “digs,” a large, terraced Fifth Avenue apartment just up from the Pierre, that she bought with another part of her inheritance. The view of the city was startling and

different, depending on the time of year.

The parties were more or less the same. A dozen guests. Talented painters, some of them known; endless English, some of them titled. Art critics and art buyers, and Edith and Phillip whenever they wanted to come. The main courses were always fancy French—even Sally couldn’t bring herself to inflict shepherd’s pie on the unsuspecting. But the wine was always “claret,” the appetizer smoked salmon from Fortnum and Mason’s.

The Bloomingdale’s furor that Edith created happened all very fast. Lady somebody or other, who was seated to Edith’s left, had never been to America before and quietly inquired as to where it might be best to shop.

Edith’s answer was obvious.

“Bite your tongue,” Sally said to Edith, and then to Lady somebody or other, “Edith’s a bit of a wag, ignore the child. Bendel’s or Bergdoff s would more than suit your needs.”

“I prefer Bloomingdale’s,” Edith replied.

“Ticky-tacky,” Sally said.

Edith turned to Lady whatever. “You’ll thank me.”

“Edith,” Sally warned, with just enough of a shift in tone to bring all other conversations to a halt. Phillip, seated between the ladies, had heard and loved these spats for years. He sat there, arms folded, the only one at the table smiling.

“Let her try it and see, Sally…”

“—why don’t you send our visitors to Lane Bryant, Edith?— no—no—I’ve got it—they can feel really ritzy and visit S. Fucking Klein’s—”

“—you’re a silly child, Sally Levinson, because I think Bloomingdale’s happens to be the greatest department store in the world—”

And now the battle was fully joined. “Greater than Harrods, you twit?”

“Far! Yes!! Now and forever!”

“Stop her, Phillip,” Sally said, reaching for his hand. “Stop her or you’ll find me in art early grave.”

Alas, it was Edith who found one…

The major reason Edith never expected trouble around 59th and Lex was simply this: Edith never expected trouble, period. And with good reason. She rarely experienced any. Oh, she broke her arm badly one year at camp. And Kate, her firstborn, came complete with asthma, serious asthma, but again, that was a disease of youth, more often than not, something you outgrew. Her many friends, when they talked about it, considered Edith just an extraordinarily lucky human being.

Not true, not true. She worked at her luck. Relentlessly. From the time she was ten. It was, perhaps, Edith’s chief inheritance from her father.

“Who is she?” Mrs. Mazursky screamed. She had to be screaming because Edith, eight and a half, could hear her mother from three rooms away. It was night and past her bedtime, lights had long since gone out, but just the same she left her bed and padded down the hall. Her parents were not screamers. Clearly an Event was taking place, and Events were meant to be Attended.

“Oh Jesus, Myrtle, close it up,” Sol Mazursky said. If Edith’s mother was a tub, the only word for Sol was “blimp.” Even if you adored him, as Edith did, the word had to come to mind. At five three and one ninety-five, svelte he wasn’t. And his shape had nothing to do with glands. He ate everything; he was constantly hungry.

“I’ll kill her!” Myrtle Mazursky went on, louder, her voice just beginning to crack.

“Myrtle, there’s no ‘her.’ I got a nose like Durante and I’m eighty pounds over, who’s gonna fall for me?”

“You’re rich,” Myrtle said. -

I didn’t know that, Edith thought, just by the open doorway now. And until then, she never had. She just more or less assumed that everybody lived in fifteen-room duplexes on Park Avenue. Or could if they wanted.

“Some riches I got—my wife could get employment shouting at the Fulton Fish Market easy.”

“Women will do anything for money. There are plenty of such people.”

“Baby, I’m gonna tell you again—I’m going out for a business appointment.”

“Don’t call me ‘baby’—and who has business at ten o’clock at night except mQnkey business?” And now came a wail. “She’s probably a shiksa.”

“There’s no one else—”

“—liar—”

“—on my honor, for Chrissakes—”

“—you’re going to see a woman, I can tell it, it’s ten o’clock at night and you just put on your best suit and you were humming while you knotted your tie, a wife notices such things—”

Then a long pause. And after that, softly: “I am going to see a woman, a shiksa, her name is Kristin with a K and she is blond—”

“—I don’t want to hear, Sol—”

“—you want to know who the enemy is, don’t you? Just shut up and let me tell you. She’s just turned twenty-four and she’s almost five eight, she towers over me, we laugh about it. We laugh about a lot of things. She thinks I’m funny, the way my wife once did.”

Deep intakes of breath from Myrtle now.

“Kristin lives on 55th Street, just off Third, and when I walk through the door she’s gonna give me a big hug, and then she’s gonna rumple my hair and lead me to the sofa and offer me a Scotch. I’m gonna say, ‘a weak one, maybe,’ and she’ll make it, like an expert, just the way I like my Chivas. A splash of soda, no ice. And then she’s gonna stir it and bring it to me and bend down and hand it over and she’ll be wearing a silk blouse but no bra, she doesn’t like bras, she doesn’t need them, and I’ll sit there all smiles and just look up at her and then it’ll be her turn to sit and guess where she’s gonna rest that perfect tush of hers.”

Pause. Silence.

Now Sol, roaring: “Right in the lap of Mister Howard L.. Kasselbaum of Chicago who keeps her and is who I’m having my goddam business meeting with/”

“Who is this Kasselbaum?”

“Precisely a question Mrs. Kasselbaum is asking these days. She thought she married a plodder, it turns out he’s Errol Flynn. He is also one of the rising stars in the Loop real estate market”

“How could you put me through this?”

“How could you think I was having an affair?”

“Why an appointment this late? Why didn’t you have dinner with him?”

“Because I like to eat with my wife, a blossoming shrew. And my daughter. Who I love more even than food. And who at this very moment is up several hours past her bedtime.”

Darn, Edith thought, I must have moved my shadow. She hesitated, then entered the huge bedroom rubbing her eyes, yawning, going quickly to her father, giving him a hug.

“No good,” her father said. “Ship her back to acting school.”

Edith went and hugged her mother.

“How much did you hear?” her father asked.

“Not anything much at all, Daddy.”

“How much did you hear?” her father asked. He was not a man who repeated himself frivolously.

“Just from ‘Who is she’ on.”

“Well, ignore it, it was nonsense, just a little show I put on to torment your mother.” Now he picked her up. She was quick and bright and pretty and already blessed with her wonderful reddish hair. “Come,” Mr. Mazursky said, and he beckoned to his wife, and they all walked downstairs in silence.

And into the living room where Edith never went, because even if you just looked at something, it broke. The living room meant this was going to be special.

“Do you think your parents love each other?”

Edith nodded. No reason not to. Not only did she think it, it was true.

“What all that up there was about, at least this is my opinion” —he looked at his wife now—”Tell me if I’m right.”

Myrtle nodded.

“What all that was about was not some nonexistent creature but just this: I work too hard. Who goes out at night for business? Ridiculous. Yes?”

Mrs. Mazursky gestured around the antique-filled room. “We don’t need any more.”

“Don’t bring money into this—money is nothing.” He turned Edith in, his lap to face him

. “Do you know what I do, Edith?”

Edith giggled. “Of course I know. You go to the office.”

Sol looked at Myrtle and smiled. “The kid understands everything.” He played with Edith’s hair gently. “My old man—”

“—you mean Grandpa?—”

“—same guy. Okay. He owned some buildings in Brooklyn. Not schlock, but not major league. I was the one convinced him to expand into Manhattan. Give it a shot.”

“And who your age has done better? Thirty-seven years old, just barely.”

Sol looked at his wife. “But I’m still not major league, baby. Can I call you ‘baby’ again?”

Myrtle nodded.

“They sit around there, those guys, and if my name is mentioned, the most they might say is, ‘Mazursky? Good man. Word means something. Got a wife going through what looks like preliminary menopause, got a daughter gonna be a great painter; nice solid club fighter. But not a champion.’ “

“What’s so terrible about that?” Myrtle said.

“Nothing. Who said ‘terrible’? Except for one thing: all I want to be in my heart is the most important real estate man in town.” He was rocking Edith now. “Honey, I want there to be a Mazursky Towers on Fifth Avenue that shines like gold. I want a Mazursky Plaza. I see Mazursky Fountains spouting all over the city. None of this comes easy, y’understand.” He looked at his wife now. “I’m gonna have to start busting my chops.”

“Start? Jesus, Sol, what do you think you’ve been doing?”

“I’m going into business with this Chicago guy. And I’m opening an office in L.A. The core’s gonna stay right here, naturally, but I want to keep ‘em guessing, all those guys at all the clubs. All kind of a game, y’understand?”

Edith wasn’t sure she did but she nodded anyway.

“Well, if you want to excel in games, tell me how you do that”