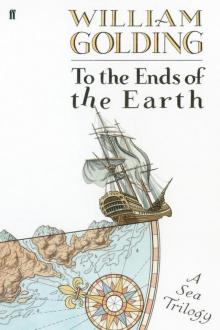

To the Ends of the Earth

William Golding

WILLIAM GOLDING

TO THE ENDS

OF THE EARTH

A SEA TRILOGY

comprising

Rites of Passage

Close Quarters

and

Fire Down Below

Table of Contents

Title Page

Foreword

Rites of Passage

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(X)

(12)

(17)

(?)

(23)

(27)

(30)

(Y)

ZETA

(Z)

(Ω)

(51)

ALPHA

(60)

(61)

BETA

GAMMA

COLLEY’S LETTER

NEXT DAY

———————

(&)

Close Quarters

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8)

(9)

(10)

(11)

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

(16)

(17)

Postscriptum

Fire Down Below

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8)

(9)

(10)

(11)

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

(16)

(17)

(18)

(19)

(20)

(21)

(22)

(23)

(24)

About the Author

By The Same Author

Copyright

Foreword

Courteous historians will generally concede that since no one can describe events with perfect accuracy written history is a branch of fiction. Similarly the novelist who deals with “before now” must pay some attention, respectful or not, to history. He is faced with a spectrum. History lies at one end—infra-red perhaps—and what is thought of as fiction occupies the opposite end—the ultra-violet. If he fails to employ his utmost accuracy in terms of the succession of commonly known events—Declaration of Independence, Battle of Waterloo et cetera—he does violate some kind of civilized expectation. He must admit to writing history with the same good humour as a historian shows when admitting that he writes fiction. It is a question of degree. The novelist, more allied than the historian to rogues and vagabonds, gets away with what he can. Generally he will find research such a bore! If you have a story to tell why not go straight on and rely on what accumulated in your head? After all, the reader will pick up your book in hopeful anticipation. He will be very willing to suspend that celebrated disbelief and be on your side. Of course there is a limit. At the play he will accept Sartre’s picture of Kean and the Prince Regent roystering together because the piece is a comedy. But who, having an average knowledge of European history, has ever felt easy at Schiller’s scene between Queen Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots? We all know they never met and our principal awareness as we watch or read is that tragedy is not being deepened, but history trivialized. So let the novelist respect history where he can!

The present volume began as three separate books and I have made tentative gestures towards turning them into a trilogy. But the truth is I did not foresee volumes two and three when I sat down to write volume one. Only after volume one was published did I come to realize that I had left Edmund Talbot, a ship and a whole ship’s company, to say nothing of myself, lolloping about in the Atlantic with their voyage no more than half completed. I got them some way on with a second volume and home and dry with a third.

It is no part of my business to give descriptions of how I, or I suppose any writer, will work. But I have to admit that some of the experiences of the writing were odd to say the least. For one thing the scene of Talbot boarding the ship, the ship herself and her people, emigrants and passengers was extraordinary and more like a memory than an imagination: which perhaps is no more than to say that our memories become imaginations and our imaginations memories. But whatever the reason, the beginning of Rites of Passage provided me with much material which I had not known was concealed there. People casually mentioned had their own lives and future. Or as Edmund Talbot might declare from his simple faith in the classics, they were there in posse who were later there in esse. The old ship herself, a main character in the story, provided the Necessity which confined people and things to certain actions and events, not others.

Nevertheless, now that all three volumes are to appear under one cover, changes and corrections and additions—to say nothing of omissions—are necessary. Rites of Passage was first published in 1980 and Close Quarters in 1987. I did not refer back to the one book as I wrote the other, relying on my unaided memory which proved to be somewhat defective. I kept in mind certain examples of people who, when publishing several volumes under one cover, had made major alterations to the text and in my opinion seriously damaged their original work. I have corrected some errors of historical fact. In sheer carelessness I had reversed the position of poop and quarterdeck, a piece of botched carpentry which remarkably enough was adjusted by a stroke of the pen—see what a delicate, not to say ethereal fabric a fiction is! Other corrections encyst a tiny fragment of arcane knowledge with which a correspondent has delighted me. Some corrections are the result of severe remarks made by professional critics, those seldom welcomed teachers.

Sometimes I have gone my own way. I am aware that people of Talbot’s social standing, let alone others among my characters, would have been affronted had a friend addressed them by their Christian name. To do so would have presumed an extraordinary degree of intimacy. Nor would such people customarily have made use of such contractions as “aren’t” or “don’t”. But amusing pastiche as it might be for a few pages to reproduce that state of affairs throughout it would end by wearying the reader. I preferred to offer him a concocted language which only now and then reverted to an archaism as a reminder of “before now”. There is one sort of critic with whom I will take what I will call mild issue. He or she believes apparently that a word only comes into being when it is printed in a dictionary. But a novelist, wading through that changing, coloured, glittering and stormy plenum in which he works will claim—must claim—that any word was likely to be in use for at least a generation before a lexicographer pinned it to his page. Of course there are many exceptions to that rule and to respect the authority of a dictionary is wise. But we must not be slavish, for that is the shortest way to a dull and sterile page. Thus, for example, “squeegee” appeared in print for the first time in 1844, so I was gently rebuked for using the word as if it had been in use in, say, 1813. Yet I should be very surprised if Nelson (died 1805) had not known of the “squeegee” and its use about the deck—and known too of “squeege” as a verb—since that appeared in print as early as 1782. This leads conveniently enough to a note about “Navalese” or what Mr Talbot called “Tarpaulin”, a better word, I think, and hope to find one day in the third edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. I learnt this language first of all from books and later from service in the Royal Navy during the Second World War. The language was one of my few pleasures during that experience and I immersed myself in it to the exte

nt that by the end of the war professionals sometimes had difficulty in knowing what I was talking about. I believe it was Kipling who declared that the Navy always had the right words for things. Certainly I have felt it was so, even in the bits which I invented myself.

Tarpaulin, then, pervades this book and so does class, or to use a word better understood by my characters, “rank”. This is a difficult subject since we British are still so dunked from childhood in that hierarchy we become unaware of it. Even so, English readers will pick up the social nuances readily enough since in a book they are seen objectively. My American readers will have some difficulty in this, unless of course they live and have been brought up in New England where much the same system was alive and kicking in the sixties when I became acquainted with it.

I would like to say a word on the subject of the optimism which some readers have thought to detect increasingly throughout the three volumes. As far as Great Britain was concerned Edmund Talbot and his class had considerable cause for optimism. A coalition of nations led by Britain had defeated Napoleon and they, or the British at least, would rule the world for more or less the whole century. In any case, whether the reader agrees with that statement or not, the three volumes are thought to be the work of Edmund Talbot, an intelligent but brash and optimistic young man. I myself am commonly thought to be a pessimist, a diagnosis with which I heartily disagree. Perhaps then it was my own optimism which gained the upper hand in the daily toil of putting down words. So Edmund Talbot or perhaps I myself found myself, himself or ourselves less and less inclined to portray life as a hopeless affair in the face of this enormity, that infinity and those tragic circumstances, particularly the ones which plagued poor Robert James Colley. It is my conviction, intuition, or what you may if you please call only my personal opinion, that both comedy and tragedy outside books as well as in them are subsumed in an ultimate Dazzle. Neither is a Cosmic truth, only a vivid universal one. (The separation of the meanings of Cosmic and universal is my own and unsupported as yet by the dictionary.) That was my conclusion as I was writing. I was bored with thinking—which fact will be laid to my discredit as a blasphemy if not abdication. But there are higher languages than that of the toiling mind, deeper intuitions than can be overtaken by the microscope or telescope, even a space one. They require metaphors, and mixed ones at that. So let Edmund FitzHenry Talbot achieve the degree of happiness of which he is capable. Let Mr and Mrs Prettiman at once fail and succeed in their impossible quest, finding thereby a passion which Edmund could never know.

And now my poor old ship must set sail on her last voyage. I must apologize to her for one or two inadequacies, some inaccuracies, one appalling howler concerning her construction and here and there a bit of fudge. She is or was, I have to remember, a piece of imagination which had to confront an imaginary sea. But she came to have a kind of reality, had the weight of a ship and moved with sails as ships did and do. She even had a spark of life as sailors always come to feel whether they say so or no. I am sure Edmund allowed himself to be half-convinced, standing as he did halfway between the classic and the romantic. As men forget their war service at last he will have forgotten the stench and sodden bilges of the unnamed ship and remembered only those moonlit sails, that world of whiteness which smote and blinded the very apple of the eye. However, I did have a name for her. I found it in the admiralty lists of those years and meant to include it somewhere but got no further than references which owe a certain quality to my knowledge: but I have forgotten both the name and the references so those correspondents who want to know what it was must be content with my apologies. For my part I should be happy if she were to be known only as a Good Read.

WILLIAM GOLDING

June 1991

Rites of Passage

(1)

Honoured godfather,

With those words I begin the journal I engaged myself to keep for you—no words could be more suitable!

Very well then. The place: on board the ship at last. The year: you know it. The date? Surely what matters is that it is the first day of my passage to the other side of the world; in token whereof I have this moment inscribed the number “one” at the top of this page. For what I am about to write must be a record of our first day. The month or day of the week can signify little since in our long passage from the south of Old England to the Antipodes we shall pass through the geometry of all four seasons!

This very morning before I left the hall I paid a visit to my young brothers, and they were such a trial to old Dobbie! Young Lionel performed what he conceived to be an Aborigine’s war dance. Young Percy lay on his back and rubbed his belly, meanwhile venting horrid groans to convey the awful results of eating me! I cuffed them both into attitudes of decent dejection, then descended again to where my mother and father were waiting. My mother—contrived a tear or two? Oh no, it was the genuine article, for there was at that point a warmth in my own bosom which might not have been thought manly. Why, even my father—We have, I believe, paid more attention to sentimental Goldsmith and Richardson than lively old Fielding and Smollett! Your lordship would indeed have been convinced of my worth had you heard the invocations over me, as if I were a convict in irons rather than a young gentleman going to assist the governor in the administration of one of His Majesty’s colonies! I felt much the better for my parents’ evident feelings—and I felt the better for my own feelings too! Your godson is a good enough fellow at bottom. Recovery took him all the way down the drive, past the lodge and as far as the first turning by the mill!

Well then, to resume, I am aboard. I climbed the bulging and tarry side of what once, in her young days, may have been one of Britain’s formidable wooden walls. I stepped through a kind of low doorway into the darkness of some deck or other and gagged at my first breath. Good God, it was quite nauseous! There was much bustling and hustling about in an artificial twilight. A fellow who announced himself as my servant conducted me to a kind of hutch against the vessel’s side, which he assured me was my cabin. He is a limping old fellow with a sharp face and a bunch of white hair on either side of it. These bunches are connected over his pate by a shining baldness.

“My good man,” said I, “what is this stink?”

He stuck his sharp nose up and peered round as if he might see the stink in the darkness rather than nose it. “Stink, sir? What stink, sir?”

“The stink,” said I, my hand over my nose and mouth as I gagged, “the fetor, the stench, call it what you will!”

He is a sunny fellow, this Wheeler. He smiled at me then as if the deck, close over our heads, had opened and let in some light.

“Lord, sir!” said he. “You’ll soon get used to that!”

“I do not wish to get used to it! Where is the captain of this vessel?”

Wheeler dowsed the light of his countenance and opened the door of my hutch for me.

“There’s nothing Captain Anderson could do either, sir,” said he. “It’s sand and gravel you see. The new ships has iron ballast but she’s older than that. If she was betwixt and between in age, as you might say, they’d have dug it out. But not her. She’s too old you see. They wouldn’t want to go stirring about down there, sir.”

“It must be a graveyard then!”

Wheeler thought for a moment.

“As to that, I can’t say, sir, not having been in her previous. Now you sit here for a bit and I’ll bring a brandy.”

With that, he was gone before I could bear to speak again and have to inhale more of the ’tween decks air. So there I was and here I am.

Let me describe what will be my lodging until I can secure more fitting accommodation. The hutch contains a sleeping place like a trough laid along the ship’s side with two drawers built under it. Wheeler informs me these standing bedplaces have been provided for the passengers as we go far south and such “bunks” are thought warmer than cots or hammocks. At one end of the hutch a flap lets down as a writing table and there is a canvas bowl with a bucket under i

t at the other. I must suppose the ship contains a more commodious area for the performance of our natural functions! There is room for a mirror above the bowl and two shelves for books at the foot of the bunk. A canvas chair is the movable furniture of this noble apartment. The door has a fairly big opening in it at eye-level through which some daylight filters, and the wall on either side of it is furnished with hooks. The floor, or deck as I must call it, is rutted deep enough to twist an ankle. I suppose these ruts were made by the iron wheels of her gun trolleys in the days when she was young and frisky enough to sport a full set of weapons! The hutch is new but the ceiling—the deckhead?—and the side of the ship beyond my bunk, old, worn and splintered and hugely patched. Imagine me, asked to live in such a coop, such a sty! However, I shall put up with it good-humouredly enough until I can see the captain. Already the act of breathing has moderated my awareness of our stench and the generous glass of brandy that Wheeler brought has gone near to reconciling me to it.

But what a noisy world this wooden one is! The south-west wind that keeps us at anchor booms and whistles in the rigging and thunders over her—over our (for I am determined to use this long voyage in becoming wholly master of the sea affair)—over our furled canvas. Flurries of rain beat a retreat of kettle-drums over every inch of her. If that were not enough, there comes from forward and on this very deck the baaing of sheep, lowing of cattle, shouts of men and yes, the shrieks of women! There is noise enough here too. My hutch, or sty, is only one on this side of the deck of a half-a-dozen such, faced by a like number on the other side. A stark lobby separates the two rows and this lobby is interrupted only by the ascending and enormous cylinder of our mizzen mast. Aft of the lobby, Wheeler assures me, is the dining saloon for the passengers with the offices of necessity on either side of it. In the lobby dim figures pass or stand in clusters. They—we—are the passengers I must suppose; and why an ancient ship of the line such as this one has been so transformed into a travelling store-ship and farm and passenger conveyance is only to be explained by the straits my lords of the Admiralty are in with more than six hundred warships in commission.