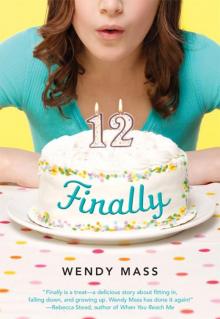

Finally

Wendy Mass

Finally

BY WENDY MASS

FOR ALLISON AND COLLEEN

AND OUR 888 ADVENTURES!

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter One

I’m a big wisher. I’ll wish on anything. Shooting stars, stray eyelashes, dandelion tops, coins in fountains. Birthday candles (my own and other people’s). Even when my glasses fog up. When I was younger, the wishes used to vary. A pony. A best friend. A new bike with streamers on the handles. A baby brother or sister. Some of these even came true (not the pony). But over the past year, every wish has been spent wishing I was twelve already, a date I’ve waited for my whole life and one that is only six weeks away. Looking back, I wish I had saved one of those wishes because, if I had, I wouldn’t be stuck in this drainpipe right now. Yes, drainpipe.

Here’s how it happened. My day started out pretty normal. My sixth grade class went on yet another field trip to the Willow Falls Reservoir. We were standing on the shoreline, listening to the guide go on about water tables and filtration systems as if they were the most fascinating things in the world. The air smelled swampy, and my orange sneakers were slowly sinking into the muddy banks. I kept glancing over at the forest on the other side of the shoreline. It reminded me of the setting of a fairy tale, like the ones my mom used to read me before bed. So peaceful and pretty, and sort of mysterious. At any minute Hansel or Gretel might dart out from between the trees. An opportunity to slip away came courtesy of Rex Bueford, who thought it would be funny to jump into the water. And it was funny, for about a second, until the tour guide told us that now our drinking water would taste like Rex’s sweat.

While our teacher yelled at Rex, and then at his friends for laughing, I slowly backed away. I kept going until I couldn’t hear the group anymore and found myself among a cluster of sharply sweet-smelling evergreens. The needles cushioned the ground beneath my feet, and a blue jay twittered on a low branch. I breathed in deep, and held the sweet air in my lungs. If my parents let me out of their sight more, I probably wouldn’t have felt the need to escape from the group, but that’s not going to change until I turn twelve. I have a whole list of things I’ll finally get to do when that day arrives.

As I stood alone in the woods, a delicious chill of anticipation ran through me, as it always did when I thought of my twelfth birthday. I leaned back against a large gray rock, intending on gazing at the puffy clouds and daydreaming about the Big Day.

The only problem? That large gray rock? Not a rock. What I thought was solid igneous rock, here on earth since the creation of the planet and therefore more than sturdy enough to support my weight, was, in fact, a rubber flap covering the opening of a narrow gray drainpipe. When I realized this, my arms and legs flailed wildly. But I couldn’t catch my balance in time. I fell, butt-first, into the pipe and was instantly wedged in. I could still see out if I craned my neck up. My sneakers dangled mere inches from the ground, but it might as well have been a mile since I couldn’t move.

“Can anyone hear me?” I called as loudly as I could. “I’m stuck! Anyone?” But my voice got carried away by the wind like it was no more than a whisper. My head filled with my grandmother’s voice. Well, this is a fine kettle of fish.

So that’s how I wound up in this predicament. It’s been a full minute now, and I haven’t managed to get unstuck. I look around in a vain attempt to find something — anything — to wish on. I consider yanking out an eyelash, but that’s kinda gross and probably painful. Plus, I don’t think the wish would count if I did it that way.

I’m able to move an arm just enough to adjust my glasses, which have fallen off one ear. Now I can assess my situation. The pipe doesn’t currently have any water running through it, so that’s one good thing. And I don’t appear to be hurt. No obvious blood or broken bones. I’m usually pretty coordinated. I can walk a straight line while patting my nose and rubbing my stomach, which isn’t as easy as it sounds. If I wasn’t stuck here, I could do it right now.

If I had a cell phone, I could use the voice-activated feature to call for help. Mental Note: Remind parents (if I ever see them again) that I wouldn’t be in this situation if they’d gotten me a phone when I’d asked. Or any of the sixty-three other times I’ve asked, even though I swore each time I wouldn’t lose it no matter what they thought. When I turn twelve, getting a phone is at the top of my list.

I watch through the gaps in the evergreens as the tour guide ushers my classmates back into the main building. The time must have come for the video portion of our visit. We’ve all been here so many times we know that old video by heart. If anyone ever quizzed us on how water makes its journey from clouds to our kitchen faucets, we’d all ace it. Still, coming here is a better field trip than the Willow Falls Historical Society, which, unless you’re a fan of musty old furniture that makes you sneeze, is deadly boring.

The last people to disappear into the building are my teacher and Rex Bueford. No doubt she’s keeping an eye on him so he can’t cause further harm to our town’s water supply. Apparently no one, not even my best friend, Annabelle, has noticed I’m missing. This doesn’t surprise me. Except for my parents (who notice me too much), I sort of fade into whatever background I’m next to, like a chameleon. I’m familiar with the habits of the chameleon because my science teacher used to keep one in a cage on his desk along with a pregnant hamster. Then last month the hamster, who was supposed to teach us about the reproductive process or whatever, got extra hungry from growing baby hamsters inside it and ate the chameleon. Well, half of the chameleon. So maybe the chameleon isn’t a good example, but seriously, whenever I show up late to the lunch table, my friends seem surprised that I haven’t been there all along.

I wish I had a book with me, since clearly I have a lot of time on my hands. I always carry around one or two, but we had to leave our backpacks on the bus. Not that I’d be able to turn the pages even if I did have a book. I wonder briefly if this drainpipe might lead somewhere as exciting as Alice’s rabbit hole or Lucy’s wardrobe, but Wonderland and Narnia have about as much in common with Willow Falls as a duck has with, well, something really different from a duck.

I try to twist my shoulders in one more futile attempt to break free. Eventually I give up and close my eyes. My mind wanders to one of my favorite daydreams: me, blowing out the candles on my birthday cake. My hair is sleek and wavy, my lips a light glossy pink, skin glowing. In my daydreams I’m always much prettier (and smarter, funnier, and more popular). I also never fall into drainpipes.

The sun warming my cheeks is soothing. And I admit, missing out on watching that old video isn’t exactly breaking me up. I’m sure my class wouldn’t board the bus without me. A few minutes later, my cheeks cool for a second, and I realize a shadow has passed across my face. I open my eyes and squint into the glare surrounding a short, plump old woman with very white hair. I hadn’t heard anyone approach. I recognize her as the old woman who had taken our tickets when we first arrived. She had welcomed us warmly, as though she was truly happy to have us visit. Now her expression is stern as she frowns down at me.

“What do you think you’re doing?” she asks, hands on her hips.

Her lips quiver a bit as she speaks, though, and I get the distinct impression she’s trying not to laugh.

I sigh, used to being falsely accused of wrongdoing by my naturally suspicious parents. “I fell.” I attempt to shrug my shoulders, but they don’t move. “And now I’m stuck,” I add.

She purses her lips, walks around the side of the pipe, then returns, shaking her head. “What’s your name?”

I’m momentarily distracted by how the duck-shaped birthmark on her cheek wiggles when she speaks. She clears her throat and asks again.

I snap my gaze away from her cheek. “Rory,” I tell her. “Rory Swenson.”

“Rory,” she repeats, putting a slight trill on the first syllable, which makes it sound a lot more exotic than it is. “Isn’t that a boy’s name?”

“It can be either one,” I explain, trying not to clench my teeth. There’s actually a boy named Rory a grade ahead of me, who Annabelle and I refer to as “Boy Rory.” He and I avoid eye contact when we pass in the hall. Annabelle always gets a good laugh out of watching my reaction when people question me about my name. With a name like hers, no one accuses her of being a boy. Girly name aside, her long shiny blond hair and pink lip gloss scream, “I’m a girl!” In contrast, my boring brown takes a lot of taming before it looks even halfway decent, and I’m not allowed to wear makeup yet. And sadly, my bod doesn’t look much different than Boy Rory’s.

The old woman tilts her head toward the building. “You’re here with the class?”

“Yes. I got lost.… I mean, I sort of wandered away. And then, well …” I gesture around me. “This happened.”

“I see,” she says, thoughtful. “Sometimes the universe, it wants us to pause for a moment. To reflect on what’s happening in our lives.”

“It does?”

She steps forward, peering at me so closely I begin to squirm. Or I would squirm, if I could move even an inch.

“What do you need to reflect on, Rory Swenson?”

“Um, me?” I stammer. “I don’t have much, you know, going on in my life right now. The last eleven years have been pretty slow.”

“Perhaps,” the old lady agrees. “But you have many things coming your way. And not much longer to wait.”

“How do you —”

She holds up a hand. “You won’t get what you want, Rory Swenson, until you see what you need.”

I smile up at her in an attempt to prove she’s not totally freaking me out. “I’ve got that covered,” I reply. “I have a list and everything. And it’s full of things I need.”

“Is that so?” she asks with a slight raise of one eyebrow.

I suddenly feel the need to defend my list. “Nothing unreasonable or anything. Just things everyone else in the sixth grade can do.”

“Everyone?” she asks.

I nod firmly.

“Well, you’re all set then.”

“Yes,” I say confidently. “I guess I am.”

“Excellent,” she says, then turns to leave.

My eyes widen. “Wait! Can you find someone to get me out of here?”

She turns back and smiles. Before I know it, she’s grabbed hold of both my wrists and tugged me right out. It takes me a few seconds to process this. I glance from the pipe, to the ground under my feet, to the woman. Standing beside her, I see I have a few inches on her, and I’m not tall by any means. Where did she suddenly get the strength to do that? I may have underestimated the senior citizen population. I stretch my sore limbs and brush the debris and dead pine needles from my clothes. “Thank you. I’m really sorry for any trouble.”

She waves me off. “No bother. It’s not every day I get to rescue a girl from a drainpipe.”

The words Wow, you’re strong for your age almost come out of my mouth, but that doesn’t sound very polite. Instead, silence descends on the woods. I never realized how loud silence could be. A movement by my foot startles me, and I jump to the side. A chipmunk scampers through the leaves and out of sight. I’m suddenly very aware that no one else is around, and glance nervously toward the building. “I should go before, you know, anyone worries about me.”

She nods curtly, and points to a large metal piece of equipment a few yards away. “I came out here to turn on the hourly drainage system. Lucky I saw you before I did that or you’d be covered in sludge right now.” She turns to go but I reach out for her arm. When she stops, I’m surprised, since I hadn’t planned on reaching out at all.

“Yes?” she asks.

“Uh, nothing,” I reply. But I don’t let go. What if I left something off my list? Before I can stop myself, I blurt out, “What did you mean before about my not getting what I want? Or what I need? Or something?”

She gently, but firmly, pulls her arm away and gestures toward the main building. “Right now what you need is to rejoin your group before they leave you here.”

I follow her gaze and see the group filing out of the building and heading toward the bus. When I turn back, she’s gone! I run over to the big metal thing, and then duck around it. The only thing I find is a startled squirrel who takes off up a tree.

A moment later I run onto the bus, out of breath, my brain swirling. The doors whoosh closed behind me. I plop down in my usual seat next to Annabelle. She turns toward me with her open and cheerful face and says, “If I have to watch that boring video one more time, I will fall to my knees and beg for mercy.”

I know I shouldn’t be surprised, but I’d have thought she’d at least question why I have mud caked on various clothes and body parts. Maybe when I’m twelve, people will finally take more notice of me. I push the old woman’s cryptic words out of my head, exhale, and say, “Me too.”

Chapter Two

In four hours and fifty-three minutes, the clock on my bright yellow wall will strike midnight. Jupiter will align with Mars. And I will finally be twelve years old. I bet my parents are hoping I’ll forget some of the things they’ve promised me over the years. But I’ve been writing them all down so not a single one slips through the cracks. I plan to present them with the list very soon.

I think Annabelle is as excited about my birthday as I am. I’m sure it hasn’t been easy for her to have a best friend whose parents are so overprotective. Annabelle’s been doing most of the things on my list for years now, like buying her own lunch in the cafeteria and walking to school and owning her own cell phone (since she was eight!). She had her ears pierced when she was just three months old. THREE MONTHS! She has five older brothers, so by the time Annabelle came along her parents were very broken in. My parents, on the other hand, met in college and got married the day after graduation. I came along a year later. They claim that as “young” parents, they remember their teen years all too well. Somehow this translates into trying to keep me totally sheltered. Now that they’re thirty-four, they don’t seem very young to me. But they’re still younger than Annabelle’s parents, who are nearly fifty. To Annabelle’s parents, the teen years are one big blur. She’s so lucky!

In preparation for the Big Day, I’ve decided to get rid of some of my more childish possessions, and surround myself with only age-appropriate objects. There’s nothing I can do about my flowered bedspread or the Kermit the Frog shade of green carpet or the yellow walls, but everything else is fair game. I scoop up the macaroni necklace I made when I was five and toss it into the big box on my bed. It lands on top of the old feety pajamas with Dora the Explorer on them and the latest issue of Highlights, which my grandmother has finally agreed to stop sending me. I raid my drawers. Anything with a decal of a rainbow, a picture of a unicorn, or my name embroidered on it gets tossed. I push aside the good memories that come floating back as I grab each shirt. I’ll make even better memories in clothes that don’t look like a six-year-old would wear them.

A few more arts-and-crafts projects, a lamp in the shape of a snowman, and my shelves are pretty bare. Except for my bookshelf. Packing away my books is going to be really hard. I decide that if I haven’t read a

book in the last year, into the box it goes. The thing is, I have a tendency to read my favorite books over and over, so the pile in the box is pretty small. I force myself to toss in some of the books that are really too young for me, no matter how often I still read them. Then I bring the snowman lamp back out of the box. It might be childish, but a girl needs to see.

Now on to the walls. The only poster on my wall is of Snoopy lying on top of his doghouse looking up at the stars. It’s the first poster that was turned into a puzzle at Dad’s factory. I feel a pang of guilt, but seriously, it has to go. No self-respecting twelve-year-old has a picture of Snoopy on her wall. I lift up a bottom corner as carefully as I can. It rips and I wince. By the time I peel it all the way off, it has ripped twice more and is really not worth saving.

I save it anyway. Then I examine the room to see if I’ve forgotten anything. My best and favorite bear, Throckmorton McGoobershneeb, watches me from his perch on my pillow. My grandfather put him in my crib when I was born, and I’ve had him ever since. Apparently, I took him with me everywhere as a baby, and it’s a wonder he still has all his arms and legs. It’s hard to tell he’s a bear at all. Annabelle says he looks more like a pig. His eyes seem to be daring me to throw him in that box.

“Sorry, Throck,” I whisper. I avert my eyes and place him inside before I can change my mind. If I’m going to leave childhood behind, I need to do it all the way.

I’m about to lift the box off the bed when my door flies open. Sawyer zooms in, one overall strap swinging crazily. My mom is two steps behind. Sawyer grabs my legs and holds on for dear life.

“Sawyer Andrew Swenson!” Mom says sternly, and reaches around for his arm. He grips my legs tighter and looks up at me with those big blue eyes of his.

“Rory, my Elmo potty is trying to swallow me!”

I pry him off me. “Elmo is not trying to swallow you,” I promise him. “At this rate, you’re going to be the only kid in diapers when you get to kindergarten.”