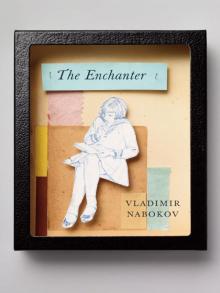

The Enchanter

Vladimir Nabokov

The Enchanter

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov

The Enchanter is the Ur-Lolita, the precursor to Nabokov’s classic novel. At once hilarious and chilling, it tells the story of an outwardly respectable man and his fatal obsession with certain pubescent girls, whose coltish grace and subconscious coquetry reveal, to his mind, a special bud on the verge of bloom.

Praise for The Enchanter

“A tale of crime and punishment… a foretaste of one of this century’s great novels.”

—Wall Street Journal

“The Enchanter is an alarming, sensuous and shimmering forerunner of Lolita…. It is a delight to have this early version of Nabokov’s strange, compelling fantasy.”

—USA Today

“Sensuous, amusing, scary… Nabokov lifts [The Enchanter] through the exhilarating artistry of his poetic and explicit language.”

—Boston Herald

“[The Enchanter is] in the top class of Nabokov’s work.”

—John Bayley, Spectator (London)

“Elegantly written and exquisitely shaped.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“The Enchanter exhibits all of [Nabokov’s] cunning and exactness of execution…. The Enchanter will indeed enchant.”

—Listener (London)

“One of the most exciting novellas ever written, Nabokov near, or at least clearly anticipating, his very best.”

—Literary Review (London)

Vladimir Nabokov

THE ENCHANTER

translated by Dmitri Nabokov

To Véra

AUTHOR’S NOTE ONE [1]

THE FIRST LITTLE THROB of Lolita went through me late in 1939 or early in 1940[2] in Paris, at a time when I was laid up with a severe attack of intercostal neuralgia. As far as I can recall, the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage. The impulse I record had no textual connection with the ensuing train of thought, which resulted, however, in a prototype of my present novel, a short story some thirty pages long.[3] I wrote it in Russian, the language in which I had been writing novels since 1924 (the best of these are not translated into English,[4] and all are prohibited for political reasons in Russia[5]). The man was a central European, the anonymous nymphet was French, and the loci were Paris and Provence. [A brief synopsis of the plot follows, wherein Nabokov names the protagonist: he thought of him as Arthur, a name that may have appeared in some long-lost draft but is mentioned nowhere in the only known manuscript.] I read the story one blue-papered[6] wartime night to a group of friends—Mark Aldanov, two social revolutionaries,[7] and a woman doctor;[8] but I was not pleased with the thing and destroyed it sometime after moving to America in 1940.

Around 1949, in Ithaca, upstate New York, the throbbing, which had never quite ceased, began to plague me again. Combination joined inspiration with fresh zest and involved me in a new treatment of the theme, this time in English—the language of my first governess in St. Petersburg, circa 1903, a Miss Rachel Home. The nymphet, now with a dash of Irish blood, was really much the same lass, and the basic marrying-her-mother idea also subsisted; but otherwise the thing was new and had grown in secret the claws and wings of a novel.

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

1956

AUTHOR’S NOTE TWO [9]

AS I EXPLAINED in my essay appended to Lolita, I had written a kind of pre-Lolita novella in the autumn of 1939 in Paris. I was sure I had destroyed it long ago but today, as Vera and I were collecting some additional material to give to the Library of Congress, a single copy of the story turned up. My first movement was to deposit it (and a batch of index cards with unused Lolita material) at the L. of C., but then something else occurred to me.

The thing is a story of fifty-five typewritten pages in Russian, entitled Volshebnik (“The Enchanter”). Now that my creative connection with Lolita is broken, I have reread Volshebnik with considerably more pleasure than I experienced when recalling it as a dead scrap during my work on Lolita. It is a beautiful piece of Russian prose, precise and lucid, and with a little care could be done into English by the Nabokovs.

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

1959

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

IN THE INTEREST of clarifying certain concentrated images (some of which originally stumped me too), and of providing the curious reader with a few informative sidelights, I have prepared a short commentary. In the interest of letting the reader get on with the story, I have placed my comments at the end and have, with one exception, avoided the distraction of footnotes in the text itself.

The Enchanter

“HOW CAN I COME TO TERMS with myself?” he thought, when he did any thinking at all. “This cannot be lechery. Coarse carnality is omnivorous; the subtle kind presupposes eventual satiation. So what if I did have five or six normal affairs—how can one compare their insipid randomness with my unique flame? What is the answer? It certainly isn’t like the arithmetic of Oriental debauchery, where the tenderness of the prey is inversely proportional to its age. Oh, no, to me it’s not a degree of a generic whole, but something totally divorced from the generic, something that is not more valuable but invaluable. What is it then? Sickness, criminality? And is it compatible with conscience and shame, with squeamishness and fear, with self-control and sensitivity? For I cannot even consider the thought of causing pain or provoking unforgettable revulsion. Nonsense—I’m no ravisher. The limitations I have established for my yearning, the masks I invent for it when, in real life, I conjure up an absolutely invisible method of sating my passion, have a providential sophistry. I am a pickpocket, not a burglar. Although, perhaps, on a circular island, with my little female Friday …(it would not be a question of mere safety, but a license to grow savage—or is the circle a vicious one, with a palm tree at its center?).

“Knowing, rationally, that the Euphrates apricot[10] is harmful only in canned form; that sin is inseparable from civic custom; that all hygienes have their hyenas; knowing, moreover, that this selfsame rationality is not averse to vulgarizing that to which it is otherwise denied access… I now discard all that and ascend to a higher plane.

“What if the way to true bliss is indeed through a still delicate membrane, before it has had time to harden, become overgrown, lose the fragrance and the shimmer through which one penetrates to the throbbing star of that bliss? Even within these limitations I proceed with a refined selectivity; I’m not attracted to every schoolgirl that comes along, far from it—how many one sees, on a gray morning street, that are husky, or skinny, or have a necklace of pimples or wear spectacles—those kinds interest me as little, in the amorous sense, as a lumpy female acquaintance might interest someone else. In any case, independently of any special sensations, I feel at home with children in general, in all simplicity; I know that I would be a most loving father in the common sense of the word, and to this day cannot decide whether this is a natural complement or a demonic contradiction.

“Here I invoke the law of degrees that I repudiated where I found it insulting: often I have tried to catch myself in the transition from one kind of tenderness to the other, from the simple to the special, and would very much like to know whether they are mutually exclusive, whether they must, after all, be assigned to different genera, or whether one is a rare flowering of the other on the Walpurgis Night of my murky soul; for, if they are two separate entities, then there must be two separate kinds of beauty, and the aesthetic sense, invited to dinner, sits down with a crash between two chairs (the fate of any dualism). On the other hand, the return journey, from the special to the simp

le, I find somewhat more comprehensible: the former is subtracted, as it were, at the moment it is quenched, and that would seem to indicate that the sum of sensations is indeed homogeneous, if in fact the rules of arithmetic are applicable here. It is a strange, strange thing—and strangest of all, perhaps, is that, under the pretext of discussing something remarkable, I am merely seeking justification for my guilt.”

Thus, more or less, fidgeted his thoughts. He was fortunate enough to have a refined, precise, and rather lucrative profession, one that refreshed his mind, sated his sense of touch, nourished his eyesight with a vivid point on black velvet. There were numbers here, and colors, and entire crystal systems. On occasion his imagination would remain chained for months, and the chain would give only an occasional clink. Besides, having, by the age of forty, tormented himself sufficiently with his fruitless self-immolation, he had learned to regulate his longing and had hypocritically resigned himself to the notion that only a most fortunate combination of circumstances, a hand most inadvertently dealt him by fate, could result in a momentary semblance of the impossible.

His memory treasured those few moments with melancholy gratitude (they had, after all, been bestowed) and melancholy irony (he had, after all, outsmarted life). Thus, back in his student days at the polytechnic, while helping a classmate’s younger sister—a sleepy, wan girl with a velvety gaze and a pair of black pigtails—to cram elementary geometry, he had never once brushed against her, but the very nearness of her woolen dress was enough to start making the lines on the paper quiver and dissolve, to cause everything to shift into a different dimension at a tense, clandestine jog—and afterward, once again, there was the hard chair, the lamp, the scribbling schoolgirl. His other lucky moments had been of the same laconic genre: a fidget with a lock of hair over one eye in a leather-upholstered office where he was waiting to see her father (the pounding in his chest—“Say, are you ticklish?”); or that other one, with shoulders the color of gingerbread, showing him, in a crossed-out corner of a sunlit courtyard, some black salad devouring a green rabbit. These had been pitiful, hurried moments, separated by years of roaming and searching, yet he would have paid anything for any one of them (intermediaries, however, were asked to abstain).

Recalling those extreme rarities, those little mistresses of his, who had never even noticed the incubus, he also marveled at how he had remained mysteriously ignorant of their subsequent fate; and yet, how many times, on a shabby lawn, on a vulgar city bus, or on some seaside sand useful only as food for an hourglass, he had been betrayed by a grim, hasty choice, his entreaties had been ignored by chance, and the delight of his eyes interrupted by a heedless turn of events.

Thin, dry-lipped, with a slightly balding head and ever watchful eyes, he now seated himself on a bench in a city park. July abolished the clouds, and a minute later he put on the hat he had been holding in his white, slender-fingered hands. The spider pauses, the heartbeat halts.

On his left sat an elderly brunette with a ruddy forehead, dressed in mourning; on his right a woman with limp, dull-blond hair was knitting industriously. His gaze mechanically followed the flitting of children in the colored haze, and he was thinking about other things—his current work, the attractive shape of his new footwear—when he happened to notice, near his heel, a large nickel coin, partially defaced by the pebbles. He picked it up. The mustachioed female on his left did not respond to his natural question; the colorless one on his right said:

“Tuck it away. It means good luck on odd-numbered days.”

“Why only on odd-numbered days?”

“That’s what they say where I come from, in———”

She named a town where he had once admired the ornate architecture of a diminutive black church.

“…Oh, we live on the other side of the river. The hillside is full of vegetable gardens, it’s lovely, there isn’t any dust or noise….”

A talkative one, he thought—looks like I’ll have to move.

And at this point the curtain rises.

A violet-clad girl of twelve (he never erred), was treading rapidly and firmly on skates that did not roll but crunched on the gravel as she raised and lowered them with little Japanese steps and approached his bench through the variable luck of the sunlight. Subsequently (for as long as the sequel lasted), it seemed to him that right away, at that very moment, he had appreciated all of her from tip to toe: the liveliness of her russet curls (recently trimmed); the radiance of her large, slightly vacuous eyes, somehow suggesting translucent gooseberries; her merry, warm complexion; her pink mouth, slightly open so that two large front teeth barely rested on the protuberance of the lower lip; the summery tint of her bare arms with the sleek little foxlike hairs running along the forearms; the indistinct tenderness of her still narrow but already not quite flat chest; the way the folds of her skirt moved; their succinctness and soft concavities; the slenderness and glow of her uncaring legs; the coarse straps of the skates.

She stopped in front of his garrulous neighbor, who turned away to rummage in something lying to her right, then produced a slice of bread with a piece of chocolate on it and handed it to the girl. The latter, chewing rapidly, used her free hand to undo the straps and with them the entire weighty mass of the steel soles and solid wheels. Then, returning to earth among the rest of us, she stood up with an instantaneous sensation of heavenly barefootedness, not immediately recognizable as the feel of skateless shoes, and went off, now hesitantly, now with easy strides, until finally (probably because she had done with the bread) she took off at full tilt, swinging her liberated arms, flashing in and out of sight, mingling with a kindred play of light beneath the violet-and-green trees.

“Your daughter,” he remarked senselessly, “is a big girl already.”

“Oh, no—we’re not related,” said the knitter. “I don’t have any of my own, and don’t regret it.”

The old woman in mourning broke into sobs and left. The knitter looked after her and continued working quickly, now and then, with a lightning motion, adjusting the trailing tail of her woolen fetus. Was it worth continuing the conversation?

The heel plates of the skates glistened by the foot of the bench, and the tan straps stared him in the face. That stare was the stare of life. His despair was now compounded. Superimposed on all his still-vivid past despairs, there was now a new and special monster…. No, he must not stay. He tipped his hat (“So long,” replied the knitter in a friendly tone) and walked away across the square. Despite his sense of self-preservation a secret wind kept blowing him to one side, and his course, originally conceived as a straight traverse, deviated to the right, toward the trees. Even though he knew from experience that one more look would simply exacerbate his hopeless longing, he completed his turn into the iridescent shade, his eyes furtively seeking the violet speck among the other colors.

On the asphalt lane there was a deafening clatter of roller skates. A private game of hopscotch was in progress at its curb. And there, waiting her turn, with one foot extended to the side, her blazing arms crossed on her chest, her misty head inclined, emanating a fierce, chestnut heat, losing, losing the layer of violet that disintegrated into ashes under his terrible, unnoticed gaze… Never before, though, had the subordinate clause of his fearsome life been complemented by the principal one, and he walked past with clenched teeth, stifling his exclamations and his moans, then gave a passing smile to a toddler who had run between his scissorlike legs.

“Absentminded smile,” he thought pathetically. “Then again, only humans are capable of absentmindedness.”

AT DAYBREAK HE DROWSILY laid down his book like a dead fish folding its fin, and suddenly began berating himself: why, he demanded, did you succumb to the doldrums of despair, why didn’t you try to get a proper conversation going, and then make friends with that knitter, chocolate-woman, governess or whatever; and he pictured a jovial gentleman (whose internal organs only, for the moment, resembled his own) who could thus gain the opportunity—thanks t

o that very joviality—to collect you-naughty-little-girl-you onto his lap. He knew that he was not very sociable, but also that he was resourceful, persistent, and capable of ingratiating himself; more than once, in other areas of his life, he had had to improvise a tone or apply himself tenaciously, undismayed that his immediate target was at best only indirectly related to his more remote goal. But when the goal blinds you, suffocates you, parches your throat, when healthy shame and sickly cowardice scrutinize your every step…

She was clattering across the asphalt amid the others, leaning well forward and rhythmically swinging her relaxed arms, hurtling past with confident speed. She turned deftly, and her thigh was bared by the flip of her skirt. Then her dress clung so closely in back that it outlined a small cleft as, with a barely perceptible undulation of her calves, she rolled slowly backward. Was it concupiscence, this torment he experienced as he consumed her with his eyes, marveling at her flushed face, at the compactness and perfection of her every movement (particularly when, having barely frozen motionless, she dashed off again, pumping swiftly with her prominent knees)? Or else was it the anguish that always accompanied his hopeless yearning to extract something from beauty, to hold it still for an instant, to do something with it—no matter what, provided there were some kind of contact, that somehow, no matter how, could quench that yearning? Why puzzle over it? She’d gather speed again and vanish—and tomorrow a different one would flash by, and thus, in a succession of disappearances, his life would pass.