Orlando

Virginia Woolf

PENGUIN BOOKS

Orlando

Virginia Woolf is now recognized as a major twentieth-century author, a great novelist and essayist and a key figure in literary history as a feminist and a modernist Born in 1882, she was the daughter of the editor and critic Leslie Stephen, and suffered a traumatic adolescence after the deaths of her mother, in 1895, and her step-sister Stella, in 1897, leaving her subject to breakdowns for the rest of her life. Her father died in 1904 and two years later her favourite brother Thoby died suddenly of typhoid. With her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, she was drawn into the company of writers and artists such as Lytton Strachey and Roger Fry, later known as the Bloomsbury Group. Among them she met Leonard Woolf, whom she married in 1912, and together they founded the Hogarth Press in 1917, which was to publish the work of T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster and Katherine Mansfield as well as the earliest translations of Freud. Woolf lived an energetic life among friends and family, reviewing and writing, and dividing her time between London and the Sussex Downs. In 1941, fearing another attack of mental illness, she drowned herself.

Her first novel, The Voyage Out, appeared in 1915, and she then worked through the transitional Night and Day (1919) to the highly experimental and impressionistic Jacob’s Room (1922). From then on her fiction became a series of brilliant and extraordinarily varied experiments, each one searching for a fresh way of presenting the relationship between individual lives and the forces of society and history. She was particularly concerned with women’s experience, not only in her novels but also in her essays and her two books of feminist polemic, A Room of One’s Own (1929) and Three Guineas (1938). Her major novels include Mrs Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927), the historical fantasy Orlando (1928), written for Vita Sackville-West, the extraordinarily poetic vision of The Waves (1931), the family saga of The Years (1937), and Between the Acts (1941). All these are published by Penguin, as are her Diaries, Volumes I-V, selections from her essays and short stories, and Flush (1933), a reconstruction of the life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel.

Brenda Lyons is a doctoral candidate at Balliol College, Oxford, where she is writing on ‘Platonic Allusions in Virginia Woolf’s Fiction’. She holds an MA in English Literature from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and has been an editor, writer and educator since the publication of Brahmins and Bullyboys. G. Frank Radway’s Boston Album (co-edited with Stephen Halpert, 1973).

Sandra M Gilbert is Professor of English at the University of California and has published widely, including four volumes of poetry and a book on D. H. Lawrence. With Susan Gubar she has co-authored The Madwoman in the Attic and two volumes of No Man’s Land: The Place of the Woman Writer in the Twentieth Century (Vol. 1: The War of the Words and Vol. 2: Sex Change) and co-edited Shakespeare’s Sisters and the Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Tradition in English.

Julia Briggs is General Editor for the works of Virginia Woolf in Penguin.

ORLANDO

A Biography

VIRGINIA WOOLF

EDITED BY BRENDA LYONS WITH

AN INTRODUCTION AND

NOTES BY SANDRA M. GILBERT

PENGUIN BOOKS

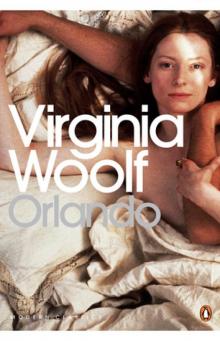

facsimile of the dust jacket of the first edition.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

www.penguin.com

Orlando first published by The Hogarth Press 1928

This annotated edition published in Penguin Books 1993

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 2000

13

Introduction and notes copyright © Sandra M. Gilbert, 1993

Other editorial matter copyright © Brenda Lyons, 1993

All rights reserved

The moral right of the editors has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN-13: 978-0-141-18427-2

ISBN-10: 0-141-18427-2

Contents

Preface 5

Chapter I 11

Chapter II 47

Chapter III 84

Chapter IV 108

Chapter V 157

Chapter VI 182

Bibliographical Note

The following is a list of abbreviated titles used in this edition.

Diary: The Diary of Virginia Woolf, 5 vols., ed. Anne Olivier Bell (Hogarth Press, 1977; Penguin Books, 1979).

Letters: The Letters of Virginia Woolf 6 vols., ed. Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann (Hogarth Press, 1975–80).

Passionate Apprentice: A. Passionate Apprentice: The Early Journals, 1897–1909, ed. Mitchell A. Leaska (Hogarth Press, 1990).

Essays: The Essays of Virginia Woolf, 6 vols., ed. Andrew McNeillie (Hogarth Press, 1986).

CE: Collected Essays, 4 vols., ed. Leonard Woolf (Chatto & Windus, 1966, 1967).

Moments of Being: Moments of Being: Unpublished Autobiographical Writings of Virginia Woolf, ed. Jeanne Schulkind (Hogarth Press, 1985).

Knole: Knole and the Sackvilles, Vita Sackville-West (Heinemann, 1922).

Letters of Vita: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf, ed. Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaska (Hutchinson, 1984).

Introduction

Orlando: Virginia Woolf’s Vita Nuova

In the autumn of 1927, Virginia Woolf was struggling to compose a critical book on ‘Fiction, or some title to that effect’. To the Lighthouse, arguably her strongest novel, had been published a few months earlier to considerable acclaim, but she was bored and troubled by the work she was doing now. Suddenly she claimed to have had a surge of inspiration. As she told the story in a letter of 9 October 1927 to the aristocratic novelist-poet Vita Sackville-West, a close friend with whom she was more than half in love at this time:

Yesterday morning I was in despair… I couldn’t screw a word from me; and at last dropped my head in my hands: dipped my pen in the ink, and wrote these words, as if automatically, on a clean sheet: Orlando: A Biography. No sooner had I done this than my body was flooded with rapture and my brain with ideas. I wrote rapidly till 12… But listen; suppose Orlando turns out to be Vita…1

Thus began Orlando, a witty and parodic ‘biography’ that Woolf was later to describe as ‘a writer’s holiday’, even while she conceded the compulsion she had felt to produce the book: ‘How extraordinarily unwilled by me but potent in its own right… Orlando was! as if it had shoved everything aside to come into existence.’2

In fact, although Woolf declared that she had embarked upon this jeu d’esprit in a kind of trance, she had been meditating a project of this sort for quite some time. In March 1927, when To the Lighthouse was at press, she commented in her diary that she was considering writing ‘a Defoe narrative for fun’. She had, she noted, ‘conceived a whole fantasy to be called “The Je

ssamy Brides” ’ about two women, ‘poor, solitary at the top of a house’ from which one could see ‘anything (for this is all fantasy) the Tower Bridge, clouds, aeroplanes’, adding that the work was

to be written… at the top of my speed… Satire is to be the main note – satire & wildness… My own lyric vein is to be satirized. Everything mocked… For the truth is I feel the need of an escapade after these serious poetic experimental books whose form is always so closely considered. I want to kick up my heels & be off.3

As the months wore on, she had refined and transformed this idea, remarking even before she wrote to Vita that

One of these days… I shall sketch here, like a grand historical picture, the outlines of all my friends… It might be a most amusing book… Vita should be Orlando, a young nobleman… & it should be truthful; but fantastic.4

A week or two later, she decided that the work would be ‘a biography beginning in the year 1500 & continuing to the present day, called Orlando: Vita; only with a change about from one sex to another.’5

At this point in her career, Woolf was at the height of her impressive imaginative and intellectual powers. Born in 1882, to Leslie Stephen, an eminent Victorian man of letters, and his beautiful, lively second wife, Julia, she had been raised in, as she put it, ‘a very communicative, literate, letter writing, visiting, articulate, late-nineteenth-century world’.6 Even before her marriage in 1912 to the socialist intellectual Leonard Woolf, she had begun to move out of that world and into the centre of the radical and rebellious circle of artists and writers that was to become known as the ‘Bloomsbury Group’. Among other activities, she had studied Greek (still at that time an unusual project for a young woman), taught at a working-women’s college in South London, worked for the women’s movement, and begun writing reviews for The Times Literary Supplement.

Now, at forty-five, Woolf was the author of five novels, which had become increasingly innovative in style, as well as a number of important critical essays and sketches. With her husband, Leonard, she owned and operated the Hogarth Press, a small but influential publishing house whose list included works by such key modernist figures as T. S. Eliot and Katherine Mansfield, along with the English translations of the complete works of Sigmund Freud. Never arrogant – she had indeed had a number of nervous breakdowns marked by severe depression and often possessed a distorted sense of her own ‘failure’ in life – she was nevertheless, in her best moments, serenely confident of her own abilities and continually determined to set herself new challenges. At the same time, having spent more than a decade developing what she called the ‘tunnelling’ method by which she conveyed the interior lives of her characters in such novels as Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, she had every reason to want to take a ‘writer’s holiday’.

Metaphorically speaking, what better companion might she have on such a holiday than the eccentric and charismatic Vita Sackville-West? Where Woolf herself was the daughter of a ‘literate, letter writing, visiting, articulate’ haut bourgeois family, Vita (short for Victoria) was indubitably a scion of the aristocracy, a class with which Woolf had always been ambivalently fascinated. Where, despite her literary successes, Woolf continually worried about money, Vita was at least putatively the heiress to a vast fortune: although her claim to Knole, her ancestral estate, had involved a complex lawsuit, the place itself was ancient, luxurious and immense. While Woolf had married a socialist intellectual whom she herself once defined as a ‘penniless Jew’, Vita was married to a representative of the British ‘establishment’ – the debonair diplomat Harold Nicolson. Where Woolf was both childless and sexually timid, Vita was both the mother of two sons and a notorious ‘Sapphist’, who made no effort to conceal her attraction to, and affairs with, women. (Indeed, where Leonard Woolf was unswervingly monogamous, even uxorious, Harold Nicolson was as flamboyantly bisexual as his wife.)

In addition, though Woolf was (or felt she was) physically fragile and odd-looking, Vita was sturdily beautiful, with a dark sensuality that she had inherited (or so Woolf speculated) from a Spanish-dancer grandmother named ‘Pepita de Oliva’, who was said to be descended from gypsies. If Woolf was (at times) almost neurasthenically intellectual and unworldly, Vita was not only a woman of the world but also a woman of action and adventure, who had briefly run off to Paris with a female lover, Violet Trefusis, just five years after her marriage to Nicolson. Despite her famous wit and charm, Woolf was often anxious about her social self-presentation – her clothes, her demeanour, even on some occasions her manners – but Vita had the careless elegance and the offhand air of command bred by generations of power. And last, but certainly not least, where Woolf was a brilliant, driven and ambitious artist, Vita was considerably less talented; although she was a successful and prolific writer herself, she could not have been regarded as a serious literary competitor.

That Vita frankly and urgently confessed to being ‘in love’ with Woolf can only have multiplied her charms from the novelist’s point of view. In a 1925 diary entry, the author-to-be of Orlando incisively summarized the traits that drew her to this compellingly seductive companion:

I like her & being with her, & the splendour – she shines in the grocer’s shop in Sevenoaks with a candle lit radiance, stalking on legs like beech trees, pink glowing, grape clustered, pearl hung. That is the secret of her glamour, I suppose. Anyhow she found me incredibly dowdy, no woman cared less for personal appearance – no one put on things in the way I did. Yet so beautiful, &c. What is the effect of all this on me? Very mixed. There is her maturity & full breastedness: her being so much in full sail on the high tides, where I am coasting down backwaters; her capacity I mean to take the floor in any company, to represent her country, to visit Chatsworth, to control silver, servants, chow dogs; her motherhood (but she is a little cold & offhand with her boys) her being in short (what I have never been) a real woman. Then there is some voluptuousness about her; the grapes are ripe; & not reflective. No. In brain & insight she is not as highly organised as I am. But then she is aware of this, & so lavishes on me the maternal protection which, for some reason, is what I have always most wished from everyone.7

From girlhood on, Woolf had enjoyed writing mock ‘histories’ of the lives of friends and relatives: in 1907 she produced a little work called ‘Friendships Gallery’, a playful life of Violet Dickinson, an older woman to whom she was much attached; and the following year she composed ‘Reminiscences’, a memoir of her sister Vanessa that was addressed to Vanessa’s children. But now, as a mature writer, she had found so intriguing a subject that she was impelled to develop the kind of informal, personal sketch she had earlier dedicated to Violet and Vanessa into a full-length, professionally expert (albeit fantastic and parodic) tribute to a person who enthralled her, a tribute that Vita’s son Nigel Nicolson was later to call ‘the longest and most charming love letter in literature’.

Beyond the personal charisma that Woolf had described with such élan in her 1925 diary, what made Vita especially fascinating to this would-be ‘biographer’ was the combination of erotic intensity and sexual ambiguity that Woolf associated with Sapphism – that is, with lesbianism. ‘These Sapphists love women; friendship is never untinged with amorosity,’ she noted with interest.8 Nor was her interest surprising, for the Bloomsbury Group, in which Woolf had moved almost from her adolescence, had long been ‘radical in its rejection of sexual taboos’, to quote her nephew and biographer Quentin Bell.9

Indeed, as the critic Alex Zwerdling has put it, the

sexual permissiveness of the group really was extraordinary: homosexuality and lesbianism not only practised but openly discussed; adulterous liaisons becoming an accepted part of the family circle; ménages à trots, à quatre, à cinq; and all this happening shortly after the death of Queen Victoria, among people raised by the old rules.10

Woolf’s sister Vanessa, for instance, married Clive Bell but had a long affair with the art historian Roger Fry and, after bearing Bell two sons, had a

daughter by the painter Duncan Grant, with whom she settled into an amicable lifelong partnership.

Woolf’s friend Lytton Strachey, to whom she was briefly engaged at one point, had numerous homosexual relationships, although he too settled into a long living-arrangement, in his case with Dora Carrington, a young woman who adored him, and her husband, Ralph Partridge, whom he adored.

Although the young Virginia Stephen tended to be an observer rather than a participant in these unconventional sexual configurations, her own feelings were never stifled by convention. As Quentin Bell observes, for example, she was clearly in love with Violet Dickinson, to whom she wrote ‘passionate letters, enchanting, amusing, embarrassing… from which one tries to conjure up a picture of the recipient’.11 And, in fact, long before she had conceived the Sapphic tale of ‘The Jessamy Brides’ which was to metamorphose into Orlando, Woolf had depicted love between women with special fervour in her novels. Rachel Vinrace, the heroine of The Voyage Out (1915), develops a keen attachment to her friend and mentor Helen Ambrose, while Katharine Hilbery, the protagonist of Night and Day (1919), and the suffragist Mary Datchet are drawn together, and the painter Lily Briscoe, a major character in To the Lighthouse, is enthralled by Mrs Ramsay, the powerfully maternal figure who dominates the work.

Most strikingly, Clarissa Dalloway, the eponymous heroine of Mrs. Dalloway (1925), remembers the moment when her girlhood friend Sally Seton kissed her on the lips as the supreme erotic experience of her life and muses on her feelings for women in one of the most explicitly sexual passages Woolf ever wrote:

… she could not resist sometimes yielding to the charm of a woman, not a girl, of a woman confessing, as to her they often did, some scrape, some folly… she did undoubtedly then feel what men felt. Only for a moment; but it was enough. It was a sudden revelation, a tinge like a blush which one tried to check and then, as it spread, one yielded to its expansion, and rushed to the farthest verge and there quivered and felt the world come closer, swollen with some astonishing significance, some pressure of rapture, which split its thin skin and gushed and poured with an extraordinary alleviation over the cracks and sores! Then, for that moment, she had seen an illumination; a match burning in a crocus; an inner meaning almost expressed. But the close withdrew; the hard softened. It was over – the moment.12