Divergent dt-1

Veronica Roth

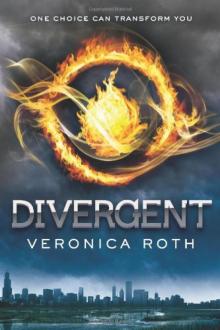

Divergent

( Divergent Trilogy - 1 )

Veronica Roth

In Beatrice Prior's dystopian Chicago, society is divided into five factions, each dedicated to the cultivation of a particular virtue — Candor (the honest), Abnegation (the selfless), Dauntless (the brave), Amity (the peaceful), and Erudite (the intelligent). On an appointed day of every year, all sixteen-year-olds must select the faction to which they will devote the rest of their lives. For Beatrice, the decision is between staying with her family and being who she really is — she can't have both. So she makes a choice that surprises everyone, including herself. During the highly competitive initiation that follows, Beatrice renames herself Tris and struggles to determine who her friends really are — and where, exactly, a romance with a sometimes fascinating, sometimes infuriating boy fits into the life she's chosen. But Tris also has a secret, one she's kept hidden from everyone because she's been warned it can mean death. And as she discovers a growing conflict that threatens to unravel her seemingly perfect society, she also learns that her secret might help her save those she loves. . or it might destroy her.

Divergent

To my mother, who gave me the moment when Beatrice realizes how strong her mother is and wonders how she missed it for so long

CHAPTER ONE

THERE IS ONE mirror in my house. It is behind a sliding panel in the hallway upstairs. Our faction allows me to stand in front of it on the second day of every third month, the day my mother cuts my hair.

I sit on the stool and my mother stands behind me with the scissors, trimming. The strands fall on the floor in a dull, blond ring.

When she finishes, she pulls my hair away from my face and twists it into a knot. I note how calm she looks and how focused she is. She is well-practiced in the art of losing herself. I can’t say the same of myself.

I sneak a look at my reflection when she isn’t paying attention — not for the sake of vanity, but out of curiosity. A lot can happen to a person’s appearance in three months. In my reflection, I see a narrow face, wide, round eyes, and a long, thin nose — I still look like a little girl, though sometime in the last few months I turned sixteen. The other factions celebrate birthdays, but we don’t. It would be self-indulgent.

“There,” she says when she pins the knot in place. Her eyes catch mine in the mirror. It is too late to look away, but instead of scolding me, she smiles at our reflection. I frown a little. Why doesn’t she reprimand me for staring at myself?

“So today is the day,” she says.

“Yes,” I reply.

“Are you nervous?”

I stare into my own eyes for a moment. Today is the day of the aptitude test that will show me which of the five factions I belong in. And tomorrow, at the Choosing Ceremony, I will decide on a faction; I will decide the rest of my life; I will decide to stay with my family or abandon them.

“No,” I say. “The tests don’t have to change our choices.”

“Right.” She smiles. “Let’s go eat breakfast.”

“Thank you. For cutting my hair.”

She kisses my cheek and slides the panel over the mirror. I think my mother could be beautiful, in a different world. Her body is thin beneath the gray robe. She has high cheekbones and long eyelashes, and when she lets her hair down at night, it hangs in waves over her shoulders. But she must hide that beauty in Abnegation.

We walk together to the kitchen. On these mornings when my brother makes breakfast, and my father’s hand skims my hair as he reads the newspaper, and my mother hums as she clears the table — it is on these mornings that I feel guiltiest for wanting to leave them.

The bus stinks of exhaust. Every time it hits a patch of uneven pavement, it jostles me from side to side, even though I’m gripping the seat to keep myself still.

My older brother, Caleb, stands in the aisle, holding a railing above his head to keep himself steady. We don’t look alike. He has my father’s dark hair and hooked nose and my mother’s green eyes and dimpled cheeks. When he was younger, that collection of features looked strange, but now it suits him. If he wasn’t Abnegation, I’m sure the girls at school would stare at him.

He also inherited my mother’s talent for selflessness. He gave his seat to a surly Candor man on the bus without a second thought.

The Candor man wears a black suit with a white tie — Candor standard uniform. Their faction values honesty and sees the truth as black and white, so that is what they wear.

The gaps between the buildings narrow and the roads are smoother as we near the heart of the city. The building that was once called the Sears Tower — we call it the Hub — emerges from the fog, a black pillar in the skyline. The bus passes under the elevated tracks. I have never been on a train, though they never stop running and there are tracks everywhere. Only the Dauntless ride them.

Five years ago, volunteer construction workers from Abnegation repaved some of the roads. They started in the middle of the city and worked their way outward until they ran out of materials. The roads where I live are still cracked and patchy, and it’s not safe to drive on them. We don’t have a car anyway.

Caleb’s expression is placid as the bus sways and jolts on the road. The gray robe falls from his arm as he clutches a pole for balance. I can tell by the constant shift of his eyes that he is watching the people around us — striving to see only them and to forget himself. Candor values honesty, but our faction, Abnegation, values selflessness.

The bus stops in front of the school and I get up, scooting past the Candor man. I grab Caleb’s arm as I stumble over the man’s shoes. My slacks are too long, and I’ve never been that graceful.

The Upper Levels building is the oldest of the three schools in the city: Lower Levels, Mid-Levels, and Upper Levels. Like all the other buildings around it, it is made of glass and steel. In front of it is a large metal sculpture that the Dauntless climb after school, daring each other to go higher and higher. Last year I watched one of them fall and break her leg. I was the one who ran to get the nurse.

“Aptitude tests today,” I say. Caleb is not quite a year older than I am, so we are in the same year at school.

He nods as we pass through the front doors. My muscles tighten the second we walk in. The atmosphere feels hungry, like every sixteen-year-old is trying to devour as much as he can get of this last day. It is likely that we will not walk these halls again after the Choosing Ceremony — once we choose, our new factions will be responsible for finishing our education.

Our classes are cut in half today, so we will attend all of them before the aptitude tests, which take place after lunch. My heart rate is already elevated.

“You aren’t at all worried about what they’ll tell you?” I ask Caleb.

We pause at the split in the hallway where he will go one way, toward Advanced Math, and I will go the other, toward Faction History.

He raises an eyebrow at me. “Are you?”

I could tell him I’ve been worried for weeks about what the aptitude test will tell me — Abnegation, Candor, Erudite, Amity, or Dauntless?

Instead I smile and say, “Not really.”

He smiles back. “Well…have a good day.”

I walk toward Faction History, chewing on my lower lip. He never answered my question.

The hallways are cramped, though the light coming through the windows creates the illusion of space; they are one of the only places where the factions mix, at our age. Today the crowd has a new kind of energy, a last day mania.

A girl with long curly hair shouts “Hey!” next to my ear, waving at a distant friend. A jacket sleeve smacks me on the cheek. Then an Erudite boy in a blue sweater shoves me. I lose my balance and fall hard on the ground.

“Out of m

y way, Stiff,” he snaps, and continues down the hallway.

My cheeks warm. I get up and dust myself off. A few people stopped when I fell, but none of them offered to help me. Their eyes follow me to the edge of the hallway. This sort of thing has been happening to others in my faction for months now — the Erudite have been releasing antagonistic reports about Abnegation, and it has begun to affect the way we relate at school. The gray clothes, the plain hairstyle, and the unassuming demeanor of my faction are supposed to make it easier for me to forget myself, and easier for everyone else to forget me too. But now they make me a target.

I pause by a window in the E Wing and wait for the Dauntless to arrive. I do this every morning. At exactly 7:25, the Dauntless prove their bravery by jumping from a moving train.

My father calls the Dauntless “hellions.” They are pierced, tattooed, and black-clothed. Their primary purpose is to guard the fence that surrounds our city. From what, I don’t know.

They should perplex me. I should wonder what courage — which is the virtue they most value — has to do with a metal ring through your nostril. Instead my eyes cling to them wherever they go.

The train whistle blares, the sound resonating in my chest. The light fixed to the front of the train clicks on and off as the train hurtles past the school, squealing on iron rails. And as the last few cars pass, a mass exodus of young men and women in dark clothing hurl themselves from the moving cars, some dropping and rolling, others stumbling a few steps before regaining their balance. One of the boys wraps his arm around a girl’s shoulders, laughing.

Watching them is a foolish practice. I turn away from the window and press through the crowd to the Faction History classroom.

CHAPTER TWO

THE TESTS BEGIN after lunch. We sit at the long tables in the cafeteria, and the test administrators call ten names at a time, one for each testing room. I sit next to Caleb and across from our neighbor Susan.

Susan’s father travels throughout the city for his job, so he has a car and drives her to and from school every day. He offered to drive us, too, but as Caleb says, we prefer to leave later and would not want to inconvenience him.

Of course not.

The test administrators are mostly Abnegation volunteers, although there is an Erudite in one of the testing rooms and a Dauntless in another to test those of us from Abnegation, because the rules state that we can’t be tested by someone from our own faction. The rules also say that we can’t prepare for the test in any way, so I don’t know what to expect.

My gaze drifts from Susan to the Dauntless tables across the room. They are laughing and shouting and playing cards. At another set of tables, the Erudite chatter over books and newspapers, in constant pursuit of knowledge.

A group of Amity girls in yellow and red sit in a circle on the cafeteria floor, playing some kind of hand-slapping game involving a rhyming song. Every few minutes I hear a chorus of laughter from them as someone is eliminated and has to sit in the center of the circle. At the table next to them, Candor boys make wide gestures with their hands. They appear to be arguing about something, but it must not be serious, because some of them are still smiling.

At the Abnegation table, we sit quietly and wait. Faction customs dictate even idle behavior and supersede individual preference. I doubt all the Erudite want to study all the time, or that every Candor enjoys a lively debate, but they can’t defy the norms of their factions any more than I can.

Caleb’s name is called in the next group. He moves confidently toward the exit. I don’t need to wish him luck or assure him that he shouldn’t be nervous. He knows where he belongs, and as far as I know, he always has. My earliest memory of him is from when we were four years old. He scolded me for not giving my jump rope to a little girl on the playground who didn’t have anything to play with. He doesn’t lecture me often anymore, but I have his look of disapproval memorized.

I have tried to explain to him that my instincts are not the same as his — it didn’t even enter my mind to give my seat to the Candor man on the bus — but he doesn’t understand. “Just do what you’re supposed to,” he always says. It is that easy for him. It should be that easy for me.

My stomach wrenches. I close my eyes and keep them closed until ten minutes later, when Caleb sits down again.

He is plaster-pale. He pushes his palms along his legs like I do when I wipe off sweat, and when he brings them back, his fingers shake. I open my mouth to ask him something, but the words don’t come. I am not allowed to ask him about his results, and he is not allowed to tell me.

An Abnegation volunteer speaks the next round of names. Two from Dauntless, two from Erudite, two from Amity, two from Candor, and then: “From Abnegation: Susan Black and Beatrice Prior.”

I get up because I’m supposed to, but if it were up to me, I would stay in my seat for the rest of time. I feel like there is a bubble in my chest that expands more by the second, threatening to break me apart from the inside. I follow Susan to the exit. The people I pass probably can’t tell us apart. We wear the same clothes and we wear our blond hair the same way. The only difference is that Susan might not feel like she’s going to throw up, and from what I can tell, her hands aren’t shaking so hard she has to clutch the hem of her shirt to steady them.

Waiting for us outside the cafeteria is a row of ten rooms. They are used only for the aptitude tests, so I have never been in one before. Unlike the other rooms in the school, they are separated, not by glass, but by mirrors. I watch myself, pale and terrified, walking toward one of the doors. Susan grins nervously at me as she walks into room 5, and I walk into room 6, where a Dauntless woman waits for me.

She is not as severe-looking as the young Dauntless I have seen. She has small, dark, angular eyes and wears a black blazer — like a man’s suit — and jeans. It is only when she turns to close the door that I see a tattoo on the back of her neck, a black-and-white hawk with a red eye. If I didn’t feel like my heart had migrated to my throat, I would ask her what it signifies. It must signify something.

Mirrors cover the inner walls of the room. I can see my reflection from all angles: the gray fabric obscuring the shape of my back, my long neck, my knobby-knuckled hands, red with a blood blush. The ceiling glows white with light. In the center of the room is a reclined chair, like a dentist’s, with a machine next to it. It looks like a place where terrible things happen.

“Don’t worry,” the woman says, “it doesn’t hurt.”

Her hair is black and straight, but in the light I see that it is streaked with gray.

“Have a seat and get comfortable,” she says. “My name is Tori.”

Clumsily I sit in the chair and recline, putting my head on the headrest. The lights hurt my eyes. Tori busies herself with the machine on my right. I try to focus on her and not on the wires in her hands.

“Why the hawk?” I blurt out as she attaches an electrode to my forehead.

“Never met a curious Abnegation before,” she says, raising her eyebrows at me.

I shiver, and goose bumps appear on my arms. My curiosity is a mistake, a betrayal of Abnegation values.

Humming a little, she presses another electrode to my forehead and explains, “In some parts of the ancient world, the hawk symbolized the sun. Back when I got this, I figured if I always had the sun on me, I wouldn’t be afraid of the dark.”

I try to stop myself from asking another question, but I can’t help it. “You’re afraid of the dark?”

“I was afraid of the dark,” she corrects me. She presses the next electrode to her own forehead, and attaches a wire to it. She shrugs. “Now it reminds me of the fear I’ve overcome.”

She stands behind me. I squeeze the armrests so tightly the redness pulls away from my knuckles. She tugs wires toward her, attaching them to me, to her, to the machine behind her. Then she passes me a vial of clear liquid.

“Drink this,” she says.

“What is it?” My throat feels swollen. I swallow hard.

“What’s going to happen?”

“Can’t tell you that. Just trust me.”

I press air from my lungs and tip the contents of the vial into my mouth. My eyes close.

When they open, an instant has passed, but I am somewhere else. I stand in the school cafeteria again, but all the long tables are empty, and I see through the glass walls that it’s snowing. On the table in front of me are two baskets. In one is a hunk of cheese, and in the other, a knife the length of my forearm.

Behind me, a woman’s voice says, “Choose.”

“Why?” I ask.

“Choose,” she repeats.

I look over my shoulder, but no one is there. I turn back to the baskets. “What will I do with them?”

“Choose!” she yells.

When she screams at me, my fear disappears and stubbornness replaces it. I scowl and cross my arms.

“Have it your way,” she says.

The baskets disappear. I hear a door squeak and turn to see who it is. I see not a “who” but a “what”: A dog with a pointed nose stands a few yards away from me. It crouches low and creeps toward me, its lips peeling back from its white teeth. A growl gurgles from deep in its throat, and I see why the cheese would have come in handy. Or the knife. But it’s too late now.

I think about running, but the dog will be faster than me. I can’t wrestle it to the ground. My head pounds. I have to make a decision. If I can jump over one of the tables and use it as a shield — no, I am too short to jump over the tables, and not strong enough to tip one over.

The dog snarls, and I can almost feel the sound vibrating in my skull.

My biology textbook said that dogs can smell fear because of a chemical secreted by human glands in a state of duress, the same chemical a dog’s prey secretes. Smelling fear leads them to attack. The dog inches toward me, its nails scraping the floor.