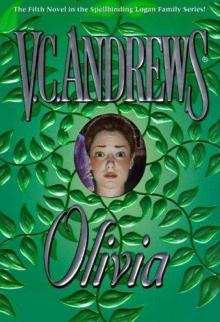

Logan 05 Olivia

V. C. Andrews

Olivia

Logan #5

V.C. Andrews

Copyright (c) 1999

ISBN: 0671007610

.

Prologue

.

Spring on the Cape always had a way of

surprising me. It was almost as if I never expected it would return. Winters could be long and dreary with days shaved down by the sharp-edge of night, but I never minded the gray skies and colder winds as much as other people did, especially my younger sister Belinda. For as long as I could remember, our schoolmates believed winter suited me better anyway. I don't recall exactly when or how it started, but one day someone referred to me as Miss Cold and Belinda as Miss Hot, and those labels followed us even to this day.

When she was a little girl, Belinda loved to burst out of the house, rush into the open air, catch the wind in her hair, and spin and laugh until she grew dizzy and fell on the sand, hysterical, excited, her eyes nearly as luminous as two birthday candles. Everything she did was an explosion. She never talked slowly, but always spoke as if she had the words crushing her lungs and had to get them out before she died. No matter what she did or said, it was usually punctuated at the end with her gasping, "I just had to tell you before I die!"

By twelve she was walking with a mature woman's swing in her hips, turning and dipping her shoulders, resembling a trained courtesan. She waved her hands about her like the fans of a geisha girl, pretending to hide her flirtatious eyes and beguiling smile between her small fingers. I saw grown men turn their heads and stare until they realized how young she was and then, almost always, take a second look just to confirm it, their faces dark with disappointment.

Her laughter was contagious. Whoever was around her at the time invariably broke into a wide smile as though she touched them with a magic wand to drive away the doldrums, their sadness or depression. People, especially boys, became blubbering amnesiacs in her presence, forgetting their responsibilities, their duties, their appointments and most of all, their own reputations. They would do the silliest things at her beck and call.

"You look like a frog, Tommy Carter. Let's hear you croak. Come on," she would taunt, and Tommy Carter, two years older, nearly a high-school senior, would crouch like a toad and go "Ribbet, ribbet," to a chorus of laughter and applause. A moment later Belinda was off, driving someone else to the precarious edge of sanity and dignity.

I always knew she would get into trouble. I just never realized how deep the pool of disaster would go. I tried to correct her behavior, teach her how to be more of a lady, and most of all, how to tread around boys and men with caution. They were always giving her gifts and she always accepted them, no matter how emphatically I warned her against it.

"It creates an obligation," I said. "Give these things back, Belinda. The most dangerous thing you can do is fill a young man's heart with false

promises."

"I don't ask them to give me things," she protested. "Well, maybe I hint at it, but I don't twist their arms. So I don't owe them a thing. Unless I want to owe them," she would add with a mischievous smile.

For some reason it was left mostly to me to give Belinda the guidance she so desperately needed.

Our mother eschewed the responsibility and obligations. She hated to hear anything nasty or see anything ugly. Her vocabulary was filled with euphemisms, words to hide the dark truths in our world. People didn't die, they "went away for good." Daddy was never mean to her. He was just "out of spirits." She made it sound as if spirits were something you could get at the gas station when your tank indicated empty. Whenever any of us were sick, she treated us as if it was our own fault. We caught colds out of carelessness and got bellyaches from eating the wrong foods. It was always the result of a poor choice we had made and if we would just try, it would all go away and everyone would be happy again.

"Close your eyes real tight and wish it away. That's what I do," she would say.

For me the worst thing was the way she viewed everything Belinda did. Her failures were never anything more than "just a temporary setback." Her pranks and little acts of mischief were always due to the "youth in her having its way. She'll grow out of it soon."

"Soon will never come, Mother," I would say with the authority of a clairvoyant.

But Mother never listened. She waved the air around her ears as if my words were nothing more than annoying flies. Any time I complained, I had "just risen from the wrong side of the bed."

Blink and it would all go away: the storms, the sickness, Belinda's bad behavior, Daddy's poor temperament, economic downswings, wars, pestilence, crime, all of it, would just go away along with anything else that was in the slightest way unpleasant.

Our mother's room was always filled with flowers. She hated dampness, musty odors. She filled her day with music-box tunes and actually wore rosetinted glasses because she hated "the dull colors, the way things faded, the annoying dark clouds that poked their bruised faces in our way."

Belinda, I decided, was far more like her than she was like our daddy. Both of us favored Mother's petite build, and it was clear early on that neither of us was ever going to be much more than five feet one or two. Mother was five feet one in her bare feet. Belinda was even smaller than I was, and, I would have to admit, had the most perfect face. Her eyes were bluer. Mine were more gray. She had a smaller nose, and her mouth was in perfect proportion. Her lips were always set in a soft twist that put a tiny dimple in her left cheek. When she was very little, Daddy would touch it with his finger and pretend it was a button. Belinda was then supposed to dance, and dance she did, flamboyant even at ages two and three.

Daddy would beam a smile so deep it went right to his heart as she turned and did pirouettes in the living room, always with her right forefinger pressed to the top of her head. Mother laughed and clapped as did any guests we had at the time.

"Can't Olivia dance, too?" Colonel Childs, one of Daddy's close friends, once asked. I'd look up and Daddy would stare at me a moment and then shake his head slowly, his eyes intense and firm on my face.

"No, Olivia doesn't dance. Olivia thinks," he said with an approving nod. "She plans and organizes. She's my little general."

After we were older and Daddy continued to refer to me from time to time as his little general, Belinda would tease me by saluting in the hallways or at the dinner table. Then she would laugh and hug me and say, "I'm just fooling with you, Olivia. Don't look so hateful."

"Being serious about yourself and having some self-respect isn't being hateful, Belinda. You should try it."

"Oh, I can't. My face won't make those lines in my forehead. My skin just snaps in revolt," she cried, rushing away with her giggles trailing behind her like the ribbon tails on a kite.

She was so frustrating all the time. Why was it that neither my mother nor my father saw what I saw? Our daddy was rarely displeased by anything Belinda said or did, and if he was, he would get over it so quickly, it was as if it had never happened. The moment after he raised his voice to her, he would check himself and seize control of that otherwise wild and fiery temper.

Many times I had witnessed his rages, saw him unleash his fury against politicians, government officials, lawyers and other businessmen. I saw him take servants to task so harshly they left his presence with their eyes down, their heads lowered, their faces pale. He was so biting and sharp with his words, he could skin someone alive with a sentence.

However, the moment he chastised Belinda, he began his retreat. I could almost see him reach out and pull the words back to his lips. If her eyes so much as glassed over with tears, he would treat her like she'd been fatally wounded, and in the end either buy her something new or promise her something wonderful. It was as if her smiles and laughter made it p

ossible for him to get through the day.

Sometimes, when we were all together at dinner or after dinner in the sitting room watching television or reading, I would look at Daddy and see him staring at Belinda, his face full of admiration, his eyes feasting on her delicate features the way an art collector might appreciate some rare antiquity, some masterpiece.

Why didn't he look at me that way? I wondered mournfully. I had never done anything that made him ashamed or unhappy. I knew he was proud of my accomplishments, but he behaved as if he expected no less. I realized he took me for granted, but I always delivered, whether it was an award at school, compliments from his business associates, or

accomplishments at home.

When I completed finishing school with the highest possible commendation, he kissed me on the forehead and shook my hand. I almost expected him to pin a ribbon on my chest and give me a promotion. My reward was to be given a place of responsibility in the family business until that day when some fine young gentleman would approach Daddy and ask for my hand in marriage. I never understood from what well he drew these buckets of hope and expectation. Daddy simply refused to believe that times were different, that young men looked for women with qualities other than a "fine family" and didn't behave so formally anymore. It was almost as if he believed he and our family were exempt from the social and political changes that affected everyone else.

If he was ever challenged in his beliefs, he would shake his head and say, "It's simply not good business for people to behave badly. There's no profit in it. Whenever you do anything in this life, you should stop and ask yourself What's the bottom line? If you do that, you'll always make the right choices."

That was something he should have taught Belinda, I thought, but he never lectured her. In fact, he rarely gave her any advice. She was permitted to be a free spirit, floating through our home and our lives, carefree, spontaneous, unrepentant and forever free of obligation, worry and responsibility.

When I questioned Daddy about her, he would nod his head, giving me the impression that I was right, and then he would stop and say, "You've just got to watch out for her, Olivia."

"When does she start to watch out for herself, Daddy? She's a high-school senior this year," I retorted.

"Some women never become anything more than older girls," he offered.

I thought he was just making excuses and it always put me in a fury. Why make excuses for her forever? Why not grab her by the nape of the neck one day and shake her until that silly, flirtatious smile fell off that porcelain face and shattered at her feet? Why not make her grow up? Why not force her to face the consequences of her actions? That is maturity, I declared in my imaginary speech, a speech my parents rarely heard, and when they did, paid little heed.

"I don't want to grow up," Belinda once had the audacity to confess. "It's boring and unpleasant and full of scowling and worries. I want to be a little girl for the rest of my life and have men take care of me."

"Don't you have any self-respect, not one iota?" I questioned.

She shrugged and softened those eyes and those lips that brought smiles to the faces of so many.

"I will when I need it," she declared.

Sometimes, talking to her tied my stomach into a knot. I would feel the very muscles in my arms and legs contract into ropes of steel. The frustration threatened to fracture me. I wanted to reach out and slap some sense into that silly little face.

And then she would hug me and say, "You will have enough self-respect for both of us, Olivia. I just know you will. I'm so lucky to have you as my older sister."

Afterward she would rush off to meet her friends and flirt with her throng of male admirers, leaving me to tend to whatever chore or duty Daddy had set out for both of us.

I must confess that sometimes I would stand there and watch her flit about and wish I was more like her. When she put her head to the pillow at night, it was always filled with candy-cane thoughts, whereas mine became Main Street for the parade of worries and the review of obligations. Her ears were full of music and promises. Mine were stuffed with facts and appointments. I was Daddy's living diary of events. He could put the tip of his finger on Belinda's dimple and make her smile the smile that warmed his heart, but he could only point his finger at me and get me to recite the purpose of a business date.

It wasn't that he was ungrateful. I believed him when he bragged about his "little general," but something in me, the Belinda in me, wanted him to mention other things about me, too. I know he thought I was more significant and more promising when it came to success for the family, but didn't he ever think of me as being pretty, too? Couldn't I be attractive and responsible simultaneously?

Unfortunately, I concluded and feared, Daddy was like most men, weak when it came to a flirtatious smile, a flighty, silly gesture, a quick hug and kiss as if affection were any sort of substitute for

responsibility and industry.

Something inside told me if I wanted men to admire me, I should imitate my sister and let bubbles float around in my head more than thoughts and ideas.

But would I be happier? Most of the men I had met in my life tried to convince me I would, but I was determined not to become some man's toy like my mother had become for my father. Belinda thinks she's happy, but she doesn't understand how little men really do think of her, how small their respect for her is, I concluded. They might crave and desire her, but when they were satisfied, when they had used her, satiated themselves and discarded her, where would she be but mired in misery, off someplace crying about her lost youth and beauty, hating the world for having such a thing as aging. She would die a little girl.

I would die a woman, and I would not be used or abused to satisfy some man. Yes, there was a part of me that wanted to be like Belinda, but that was the part men planted in me, the part I could subdue.

Call me little general. Call me Miss Cold and call Belinda Miss Hot, I thought.

But in the end, they will call me with respect, and really, in the end, what mattered more, respect or love? No one really knew what love was. How many husbands and wives had this so-called magical bond?

The choice was simple, I thought: be a dreamer or be a realist and make the day conform to what I wanted and not what I hoped.

Belinda danced and my father smiled. My mother fled from pain and darkness, and I, I stood behind them all, like some impregnable wall, keeping disaster away from our doorstep. In the end they would all appreciate me.

And what would anyone want more than that?

The tinkle of Belinda's laughter fell along the dark corridors of my own doubt, filling my mind with little sparks, keeping me from being absolutely sure.

1

Cries in the Night

.

At first I thought I was dreaming, for when I

woke and opened my eyes, I heard nothing but the low whistle of the wind blowing up from the ocean. The stream of moonlight filtering through my sheer white curtain bathed the walls in a pale yellow glow. My window shutters banged against the clapboard and then, I heard the sound again, this time with my eyes wide. I listened, my heart tapping like a steadily growing drumbeat in anticipation of some important announcement or event. After a moment I heard it once more.

It sounded like a cat in heat, but we had no cats. Daddy hated pets, finding them more of an obligation than a pleasure. The only animals he said had any purpose was a watchdog or a seeing-eye dog, and he had no need for either. Our house was far enough away from the downtown Provincetown area and surrounded by walls ten feet high with an entrance gate Daddy had Jerome, our grounds keeper, lock every night. Daddy also kept his shotgun under the bed, "just in case." It was, he said, a lot cheaper than feeding some mongrel, and that, he concluded, "was the bottom line."

This time the sound was even louder. I sat up so quickly someone would think I had springs under me, but I realized the shrill cries were not in my imagination or from nightmares. The noise was coming through the wall betwee

n my room and Belinda's. It wasn't a howl, exactly, nor was it a screech. There was something familiar about the sound and yet something starkly unusual. It was certainly not a noise Belinda would make herself, but there was no doubt it was emanating from her bedroom.

I stepped off my bed, scooped up my robe from the chair beside my bed, and shoved my arms into the sleeves as I left my room. Daddy and Mother had already come out of their bedroom. Mother was still in her nightgown and Daddy was in his pajamas. The dreadful sound continued.

"What in all hell . . ." Daddy started for Belinda's closed door. I followed, with Mother a distant third, but when Daddy opened the door and realized the horrendous scream came from Belinda, Mother charged forward.

"Winston, what's wrong?" she cried.

Daddy flicked on the light, illuminating the most amazing and alarming sight before us. Belinda was sprawled on the floor, her nightgown bloody and crumbled up to her breasts. There, lying between her legs was a newly-born infant, the umbilical cord and afterbirth still attached.

Belinda's eyes were wild with terror. The baby's eyes were closed, and it jerked its tiny arm and then stopped moving.

"Jesus, Mary and Joseph," Daddy exclaimed under his breath, his feet hammered to the floor by astonishment.

Mother's eyes rolled back in her head and she folded at Daddy's feet as if her spinal cord had turned to jelly. "Leonora!"

"Take her to bed, Daddy," I said. "I'll see to Belinda."

He gazed back at the sight once more to confirm it was indeed still there and not in his imagination. Then he squatted, slipped his arms under Mother and lifted her like she was a baby herself, carrying her back to their bedroom.

I entered Belinda's room, quickly closing the door behind me. Our servants downstairs were surely awake by now as well. Belinda whimpered. Her eyes rolled as if the room were spinning. She had her arms raised, but she was afraid to touch the infant or herself.

"I couldn't stop it. It just happened, Olivia," she moaned. Her whole body shook. I stepped up to her and gazed down at the bloody sight.