The Complete Stories of Truman Capote

Truman Capote

TRUMAN CAPOTE

THE COMPLETE STORIES

Truman Capote was born Truman Streckfus Persons on September 30, 1924, in New Orleans. His early years were affected by an unsettled family life. He was turned over to the care of his mother’s family in Monroeville, Alabama; his father was imprisoned for fraud; his parents divorced and then fought a bitter custody battle over Truman. Eventually he moved to New York City to live with his mother and her second husband, a Cuban businessman whose name he adopted. The young Capote got a job as a copyboy at The New Yorker in the early forties, but was fired for inadvertently offending Robert Frost. The publication of his early stories in Harper’s Bazaar established his literary reputation when he was in his twenties, and his novel Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), a Gothic coming-of-age story that Capote described as “an attempt to exorcise demons,” and novella The Grass Harp (1951), a gentler fantasy rooted in his Alabama years, consolidated his precocious fame.

From the start of his career Capote associated himself with a wide range of writers and artists, high-society figures, and international celebrities, gaining frequent media attention for his exuberant social life. He collected his stories in A Tree of Night (1949) and published the novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958), but devoted his energies increasingly to the stage—adapting The Grass Harp into a play and writing the musical House of Flowers (1954)—and to journalism, of which the earliest examples were “Local Color” (1950) and “The Muses Are Heard” (1956). He made a brief foray into the movies to write the screenplay for John Huston’s Beat the Devil (1954).

Capote’s interest in the murder of a family in Kansas led to the prolonged investigation that provided the basis for In Cold Blood (1966), his most successful and acclaimed book. By “treating a real event with fictional techniques,” Capote intended to create a new synthesis: something both “immaculately factual” and a work of art. However its genre was defined, from the moment it began to appear in serialized form in The New Yorker the book exerted a fascination among a wider readership than Capote’s writing had ever attracted before. The abundantly publicized masked ball at the Plaza Hotel with which he celebrated the completion of In Cold Blood was an iconic event of the 1960s, and for a time Capote was a constant presence on television and in magazines, even trying his hand at movie acting in Murder by Death.

He worked for many years on Answered Prayers, an ultimately unfinished novel that was intended to be the distillation of everything he had observed in his life among the rich and famous; an excerpt from it published in Esquire in 1975 appalled many of Capote’s wealthy friends for its revelation of intimate secrets, and he found himself excluded from the world he had once dominated. In his later years he published two collections of fiction and essays, The Dogs Bark (1973) and Music for Chameleons (1980). He died on August 25, 1984, after years of problems with drugs and alcohol.

FIRST VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, SEPTEMBER 2005

Compilation copyright © 2004 by The Truman Capote Literary Trust

Biographical note copyright © 1993 by Random House, Inc.

Introduction copyright © 2004 by Reynolds Price

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2004.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Owing to limitations of space, story credits can be found beginning on this page.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Random House edition as follows:

Capote, Truman.

[Short Stories]

The complete stories of Truman Capote / introduction by Reynolds Price.

p. cm.

I. Price, Reynolds. II. Title.

PS3505.A59A6 2004

813’.54—dc22

2004046876

eISBN: 978-0-345-80306-1

www.vintagebooks.com

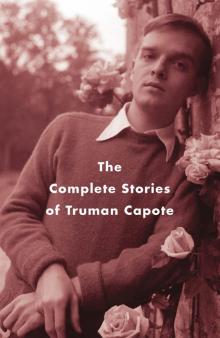

Cover photograph by Slim Aarons/Getty Images

Cover design by Megan Wilson

v3.1_r2

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction: Usable Answers by Reynolds Price

THE COMPLETE STORIES OF

TRUMAN CAPOTE

The Walls Are Cold

A Mink of One’s Own

The Shape of Things

Jug of Silver

Miriam

My Side of the Matter

Preacher’s Legend

A Tree of Night

The Headless Hawk

Shut a Final Door

Children on Their Birthdays

Master Misery

The Bargain

A Diamond Guitar

House of Flowers

A Christmas Memory

Among the Paths to Eden

The Thanksgiving Visitor

Mojave

One Christmas

Story Credits

Other Books by This Author

Also by Truman Capote

INTRODUCTION

Usable Answers

Reynolds Price

America has never been a land of readers, not of what’s called literary fiction in any case. And in the twentieth century, only two writers of distinguished fiction managed to become American household names—Ernest Hemingway and Truman Capote. Each of them succeeded in that dubious distinction by means which hardly included their often distinguished work. Hemingway—strapping, bearded and grinning—reached most households in the pages of Life, Look and Esquire magazines with a fishing rod or a shotgun in hand or a hapless Spanish bull nearby, on the verge of being killed. After the publication of Capote’s nonfiction account of a mass murder in rural Kansas, he (in his tiny frame and high voice) became the instant star of numerous television talk shows—a fame that he maintained even as his consumption of liquor and drugs left him a bloated shadow of his former self. And even now—with Hemingway dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound since 1961 and Capote of relentless self-abuse since 1984—their best work continues to be gravely denigrated by understandably disaffected critics and readers. Yet many of Hemingway’s lucid short stories and at least three of his novels are as near perfection as prose ever manages to be, and Capote left behind not only a riveting crime narrative but also a quantity of early fiction (three brief novels and a handful of short stories) that awaits the close attention and measured admiration he long since earned.

Capote’s short stories are gathered here; and they range over most of his creative life up until the devastating success of In Cold Blood, which was published in 1965 when he was little more than forty years old. With the brilliantly self-managed publicity bonanza of that riveting crime tale, Capote not only landed on millions of American coffee tables and on every TV screen, he further endeared himself to the denizens of café society and the underfed fashion queens whom he’d so bafflingly pursued in earlier years.

Soon he would announce his intention to publish a long novel that would examine the society of rich America as mercilessly as Marcel Proust had portrayed French high society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And he may well have gone to work on his plan. Yet one consideration that Capote never seemed to discuss, or even be questioned about in public, was crucial to the eventual collapse of his vision (if he ever had one). Proust’s society was one of blood, unshakably founded on positions of French social eminence that were reared u

pon centuries-old money, property and actual power over the lives of other human beings. Capote’s society merely teetered upon the unsubstantial and finally inconsequential grounds of financial wealth; fashionable clothes, houses and yachts and occasional physical beauty (the women were frequently beautiful, the men very seldom so). Any long fictional study of such a world was likely to implode upon the ultimate triviality of its subject.

When he surfaced from punishing rounds of frenetic social and sexual activity and began to publish excerpts from his novel—fewer than two hundred pages—Capote found himself abandoned overnight by virtually all his rich friends; and he fled into a nightmare tunnel of drugs, drink and sexual commitments of the most psychically damaging sort. Despite numerous attempts at recovery, his addictions only deepened; and when he died, a miserable soul well short of old age, he left behind only a few pages of the tall stack of manuscript he claimed to have written on his great novel. If more of the novel ever existed, he’d destroyed the pages before his death (and his closest friends disagreed on the likelihood of the existence of a significant amount of work).

Such a tragic arc tempts any observer to make some guess at its cause, and what we know of Capote’s early life provides us a near-perfect graph for any student of Freud who predicts that a disastrous adulthood is the all but inevitable result of a miserable childhood. And Gerald Clarke’s careful biography of Capote charts just such a dislocated, lonely and emotionally deprived childhood, youth and early manhood. Young Truman was, in essence, deserted by a too-young and sexually adventurous mother and a bounder of a father who left him in small-town Alabama with a houseful of unmarried cousins (cousins and neighbors who at least rewarded him with a useful supply of good tales).

When his mother eventually remarried and summoned the adolescent Truman to her homes in Connecticut and New York, she changed his legal surname from Persons to the name of her second husband, Joe Capote, a Cuban of considerable charm but slim fidelity. The physically odd boy—whose startlingly obvious effeminacy of voice and manner greatly distressed his mother—attended good Northern schools where he performed poorly in virtually all subjects but reading and writing. Then determined on a writer’s career, he decided against a college education, took a small job in the art department at The New Yorker, launched himself into a few of the mutually exclusive social circles of big-city writing and nighttime carousing and began serious work on the fiction that would bring him his premature fame.

The earliest stories gathered here clearly reflect his reading in the fiction of his contemporaries, especially in the quite recent stories of his fellow Southerners, Carson McCullers from Georgia and Eudora Welty from Mississippi. Capote’s “Miriam,” with its perhaps too-easy eeriness, and “Jug of Silver,” with its affectionate small-town wit, may suggest McCullers’s own early stories. And his “The Shape of Things,” “My Side of the Matter” and “Children on Their Birthdays” may be readily seen as not-quite-finished stories from Welty, especially “My Side of the Matter” with its close resemblance to Welty’s famous “Why I Live at the P.O.”

Yet Capote’s childhood, spent in a middle-class white world so close to Welty’s and McCullers’s own—and in a household uncannily like the one described in Welty’s comic monologues—might well have extracted such stories from a talented young writer, even if he had never encountered a Welty or McCullers story (Welty told me that when she was undergoing her Paris Review interview in 1972, George Plimpton suggested that the interviewer raise the question of her influence on Capote’s early work; and she declined to discuss the matter, having no desire to entertain any claim of another writer’s dependence upon her).

In general, however, by the late 1940s, Capote’s fictional voice was clearly his own. His weirdly potent first novel—Other Voices, Other Rooms in 1948—erected as it is upon the conventional grounds of modern Southern Gothic ends as an unquestionably original structure that, even now, is a powerful assertion of the pain of his own early solitude and his bafflement in the face of the sexual and familial mysteries that had begun to impinge upon his confidence and would ultimately contribute heavily to his eventual collapse in agonized shame, even in the midst of so much later artistic, social and financial success. The same dilemmas are on partial display in short stories like “The Headless Hawk,” “Shut a Final Door” and “A Tree of Night.”

But given the fact that homosexuality was then a troubling daily reality for Capote, and given that American magazines were still averse to candid portrayals of the problem, perhaps we can comprehend now why such early stories lack a clear emotional center. Had he written short stories as candid in their views of homosexuality as his first novel managed to be, they would have almost certainly gone unpublished, certainly not in the widely read women’s magazines which were the centers of much of the best short fiction of the time. It was in his second novel—The Grass Harp of 1951—that he discovered a mature means of employing important areas of his own past to empower fiction that would ring with convincing personal truth. Those areas centered around, not sexuality but the deeply encouraging devotion he received in childhood from a particular cousin and from the places he and that friend frequented in their games and devotions. The cousin was Miss Sook Faulk, a woman so slender in her concerns and affections that many thought her simple-minded, though she was only (and admirably) simple; and in the years that she and the young Truman shared a home, she gave him the enormous gift of a dignified love—a gift he’d received from no closer kin.

Among these stories, that depth of feeling and its masterful delivery in the memorably clear prose which would mark the remainder of Capote’s work, is visible above all in his famous story “A Christmas Memory,” and in the less well-known “The Thanksgiving Visitor” and “One Christmas,” the last of which may be a little sweet for contemporary tastes but, true as it is, is almost as moving in its revelation of yet another early wound—this one administered by a feckless and distant father. It’s likely that more Americans know “A Christmas Memory” through an excellent television film, with an extraordinary performance by Geraldine Page; but anyone who reads the actual tale has encountered a feat rarer than any screen performance. By the sheer clarity of his prose and a brilliant economy of ongoing narrative rhythm, Capote cleanses of any possible sentimentality a small array of characters, actions and emotions that might have gone foully sweet in less watchful and skillful hands. Only Chekhov comes to mind as sufficiently gifted in the treatment of similar matter.

But once possessed of the skills to deliver the width of emotion he wished for, Capote was not limited to the recounting of childhood memory, more or less real or entirely invented. Like many fiction writers, he wrote fewer and fewer short stories as he grew—life often becomes more intricate than brief forms can easily contain. But one story, “Mojave” from 1975, embodies brilliantly and terribly the insights acquired in his years among the rich. Had he lived to write more such angled quick glimpses of their hateful world, he would never have left us with the sense of incompletion that the baffled rumors of a long novel have done.

And had his decades away from the Southern source of all his best fiction—long and short—not left him uninterested, or incapable, of writing more about that primal world, we would likewise have more cause for gratitude for his work. In fact, however, if we lay Capote’s fiction atop the stack that includes In Cold Blood and a sturdy handful of nonfiction essays, we will have assembled a varied body of work that’s equaled by only a very few of his contemporaries in the United States of the second half of the twentieth century.

This man who impersonated an exotic clown in the early, more private years of his career and then—pressed by the heavy weight of his past—became the demented public clown of his ending, left us nonetheless sufficient first-class work to stand him now—cool decades after his death—far taller than his small and despised body ever foretold. In 1966 when he’d begun to announce his work on a long novel—and to take huge publisher’s advances for it

—he said he’d entitle the book Answered Prayers. And he claimed that Answered Prayers was a phrase he’d found among the sayings of St. Teresa of Avila—More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones. There are few signs that prayers to God or to some intercessory saint—say a seizure-ridden Spanish mystic or his simple cousin Sook—were ever a steady concern of Truman Capote’s life, but his lifelong pursuit of wide attention and wealth was appallingly successful. Before he was forty, he’d achieved both aims, in tidal profusion and utter heartbreak.

In his final wreckage, this slender collection of short stories may well have seemed to Capote the least of his fulfillments; but in the arena of expressed human feeling, they represent his most impressive victory. From the torment of a life willed on him, first, by a viciously neglectful father and a mother who should never have borne a child and, then, by his own refusal to conquer his personal hungers, he nonetheless won on the battlefield of English prose these stories that, at their best, should stand for long years to come as calm enduring prayers and accomplished blessings—free for every reader to use.

REYNOLDS PRICE was born in Macon, North Carolina in 1933. Educated at Duke University and, as a Rhodes Scholar, at Merton College, Oxford University, he has taught at Duke since 1958 and is J.B. Professor of English. His first novel, A Long and Happy Life, was published in 1962 and won the William Faulkner Award. His sixth novel, Kate Vaiden, was published in 1986 and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. Noble Norfleet, his twelfth novel, was published in 2002. In all, he has published thirty-five volumes of fiction, poetry, plays, essays and translations. Price is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and his work has been translated into seventeen languages.

THE COMPLETE STORIES OF