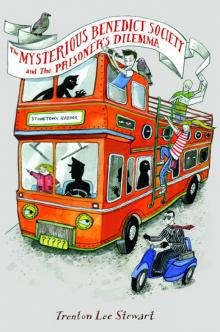

The Mysterious Benedict Society and the Prisoner's Dilemma

Trenton Lee Stewart

Copyright

Copyright © 2009 by Trenton Lee Stewart

Illustrations copyright © 2009 by Diana Sudyka

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: October 2009

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07246-5

For Sam and Jake

—T.L.S.

Contents

Copyright

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Monster in the Basement

Real and Official Matters

Through the Listening Glass

What May Be Perceived

The Unwelcome Visitor

The Little Girl in the Big Chair

Leap Years and Napmares

S.Q.’s Greatest Fear

Darkness Falls

Setups, Clues, and Likely Stories

Tricky Lines and Heavy Traffic

Cowdozers and Rendezvous

Breakable Codes and Findable Clues

The Shark and His Prey

Secret Communications

Stated Reasons and Sudden Insights

The Window of Opportunity

The Courtyard Conflicts

Bucket vs. Briefcase

The Sorting Out

Projects and Poetry

The More Things Change

In a city called Stonetown, on the third floor of an old, gray-stoned house, a boy named Reynie Muldoon was considering his options. He was locked inside an uncomfortably warm room, and the only way out was to make an unpleasant decision. Worse, locked in the room with him—and none too happy about it—was a particularly outspoken four-year-old named Constance Contraire, who from the outset of their confinement had been reciting ill-tempered poems to express her displeasure. Reynie, though three times Constance’s age and probably fifty times as patient, was beginning to feel ill-tempered himself. He had the hot room and the cranky girl to endure. Constance couldn’t possibly want out more than he did. The problem was what it would cost.

“Can we just review our options?” Reynie said as patiently as he could. “We’ll get out sooner, you know, if we come to a decision.”

Constance lay on her back with her arms thrown out wide, as if she had collapsed in a desert. “I’ve already come to a decision,” she said, swiveling her pale blue eyes toward Reynie. “You’re the one who hasn’t made up his mind.” She brushed away a wisp of blond hair that clung to her damp forehead, then quickly flung her arm out again, the better to appear downcast and miserable. She panted dramatically.

“We’re supposed to be in agreement,” Reynie said, keeping his face impassive. Signs of annoyance only encouraged Constance, and she was always on the lookout for them. “You can’t just tell me what to do and expect me to go along.”

“But that’s exactly what I did,” said Constance, “and you’re taking forever, and I’m roasting!”

“You might consider taking your cardigan off,” said Reynie, who as usual had shed his own the moment they came upstairs. (The heating system in this old house was terribly inefficient; the first floor was an icebox, the third floor a furnace.) Constance gave a little start and fumbled at the buttons of her wool cardigan, muttering “better off” and “sweater off” as she did so. Already composing another poem, Reynie realized with chagrin. Her last one had featured a “dull goon” named “Muldoon.”

Reynie turned away and began to pace. What should he do? He knew that Rhonda Kazembe—the administrator of this disagreeable little exercise—would soon return to ask if they’d made up their minds. Evidently their friends Sticky and Kate, locked in a room down the hall, had settled on their own team’s decision right away, and now were only waiting for Reynie and Constance. At least that’s what Rhonda had said when she checked on them last. For all he knew, she might not have been telling the truth; that might be part of the exercise.

It certainly wouldn’t have been their first lesson to contain a hidden twist. Under Rhonda’s direction, the children had participated in many curious activities designed to engage their interest and their unusual gifts. Gone were the days of studying in actual classrooms—for security reasons they were unable to attend school—but any odd space in this rambling old house might serve as a classroom, and indeed many had. But this was the first time they had been locked up in the holding rooms, and it was the first exercise in which their choices could result in real—and really unpleasant—consequences.

The children’s predicament was based, Rhonda had told them, on an intellectual game called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Sticky, naturally, had read all about it, and at Rhonda’s prompting he had explained the premise to his friends.

“There are thousands of variations,” Sticky had said (and no doubt he knew them all), “but it’s often set up like this: Two criminals are arrested, but the police lack evidence for a major conviction, so they put the prisoners in separate rooms and offer each one the same deal. If one prisoner betrays his friend and testifies against him, while the other prisoner remains silent, the traitor goes free and his partner receives a ten-year prison sentence.”

“So much for sticking together,” Kate had observed.

“Well, they can stick together, right? They can both remain silent. But if they do that, then both are sentenced to six months in jail for a minor charge. So both get punished, although it’s a relatively light punishment considering the alternatives.”

“And what if each one betrays the other?” Reynie had asked.

“Then they both receive five-year sentences. Not good, obviously, but much better than ten. So the dilemma is that each prisoner must choose to betray the other one or remain silent—without knowing what the other one’s going to do.”

It was this last part that had gotten so complicated for Reynie, because the more he thought about it—pacing back and forth in this hot room—the more convinced he became that he did know. He glanced over at Constance, now making a show of letting her tongue loll out the way dogs do when they’re overheated. “Constance, do you think Rhonda was lying about Sticky and Kate making up their minds so fast?”

“No, she was telling the truth,” said Constance, who was even better than Reynie at sensing such things—if she was paying attention. You couldn’t always count on that.

“That can only mean one thing, then.”

Constance rolled her eyes. “To you, maybe.”

“Yes, to me,” Reynie sighed. Although in some respects he seemed the most average of boys—with average brown hair and eyes, an average fair complexion, and an average inability to keep his shirt tucked in—Reynie was anything but average when it came to figuring things out. That included people, especially such close friends as Sticky Washington and Kate Wetherall, whom he knew better than anyone. If Sticky and Kate had made their decision so quickly, then it was clear to Reynie what they had decided. Less clear was what to

do about it.

Reynie continued his pacing. If only there weren’t real consequences! But they were real enough, all right, even if they weren’t actual prison sentences. Rhonda had carefully explained them all:

The children would be split into two teams of “prisoners.” If both teams chose Option A—to remain silent—then both would receive extra kitchen duty for the rest of the day. (No small task, for including the children’s families there were thirteen people residing in this house, and every meal produced a shocking quantity of dishes.) If, however, both teams chose Option B—to betray—then both would receive extra kitchen duty for the rest of the week. And of course the final possibility was the most diabolical of all: If one team chose silence while the other chose betrayal, then the traitors would get off scot free while the others did the entire week’s dishes by themselves.

“Okay, so that’s three meals a day,” Sticky had said, “with an average of thirteen place settings per meal—”

“Not to mention pots and pans,” Kate pointed out.

“And snacks,” Reynie said.

Sticky’s eyes were growing large with alarm. “And five days left in the week…”

As these daunting prospects were sinking in—and before the children could make any private pacts—Rhonda had ushered them into their separate holding rooms to discuss the options. But discussion was impossible with Constance, who had insisted from the start that they choose Option B. Betrayal was the only sensible option, she argued, since Sticky and Kate would surely choose Option B as well. After all, neither team would care to risk all that kitchen duty without help.

But Reynie not only found this strategy distasteful (he could imagine sentencing enemies to the sink, but his friends?), he also knew what the other team had chosen—and it wasn’t Option B. Sticky and Kate hadn’t taken time to reflect. If they had, they might have considered that Reynie’s confinement would be more miserable than theirs; that no one in the world was more stubborn than Constance; and that in Reynie’s place they, too, would be sorely tempted to end the ordeal by yielding to her.

But Sticky and Kate had gone with their first impulse. The only decent choice, in their view, would be to remain silent, and they would expect Reynie to choose the decent thing too. Even if Constance rather predictably insisted on Option B—well, Reynie would just find a way to change her mind! Such was their confidence in him, Reynie knew. It made betraying them all the more painful to contemplate.

He couldn’t help contemplating it, though. Rhonda had said the team must be in agreement, and Constance refused to budge. How long might they be stuck in here? Another hour? Another two? Reynie grimaced and quickened his pacing. He couldn’t bear to imagine his friends’ look of disappointment, but Constance was clearing her throat now—she was about to launch into another grating poem, and Reynie didn’t know if he could bear that, either. Should he threaten to tell Rhonda about Constance’s secret candy stash? No, Constance wasn’t susceptible to threats, and she would make Reynie pay dearly for the attempt. The last time he had tried something like that, she’d peppered his toothbrush.

Constance drew a deep breath and sang out:

There once was a ninny called Reynie

Who thought there was one choice too many

Because he was wimpy

He—

“Enough!” Reynie cried, clutching his head. Maybe he could just apologize to Sticky and Kate and—yes, he would even offer to help them with the dishes. Anything but this.

“So we’re going with Option B?” asked Constance brightly. She looked exceedingly pleased.

“Why on earth would you do that?” said a metallic voice out of nowhere.

Reynie and Constance jumped. They had thought themselves alone—and indeed they still appeared to be. Other than several crowded bookshelves and a few tall stacks of books on the floor, the room was empty. There was a big arched window, but it remained firmly closed, and nothing appeared beyond the glass except the gray January sky.

“Did you hear that?” Constance asked, her eyes wide. “Or was it, you know—?” She tapped her head.

“No, I heard it, too,” Reynie assured her, casting about for the source. “Where are you, Kate?”

“In the heating duct, silly,” replied Kate’s voice. “Behind the register. There’s a pile of books in front of it.”

Reynie found the heat register behind a waist-high stack of science journals. Quickly moving the journals aside, he peered through the grille to find Kate’s bright blue eyes peering back at him. She slipped her Swiss Army knife through the grille. “Let us out, will you? Sticky’s feeling a bit claustrophobic.”

Reynie hastened to find the screwdriver on the knife. The heat register was quite old and ornate, and slightly rusty, and it took him a while to get the register off—he was much less nimble with tools than Kate. This was nothing to be ashamed of (no one could compare to Kate when it came to physical ability), but Reynie was feeling ashamed, regardless, for having been about to betray her in the game, and he was grateful for her stream of friendly chatter as he worked.

“We kept wondering what was taking you so long,” she was saying in her usual rapid-fire way, “and finally we decided we should come check. I thought maybe you’d had a heat stroke, but Sticky figured Constance was giving you serious trouble. And he was right, wasn’t he? Shame on you, Constance! That was an awfully mean-spirited poem. Although, I have to admit I was curious to find out what sort of insult rhymes with ‘wimpy.’”

“And now you’ll never know,” humphed Constance, crossing her arms.

At last Reynie pulled the register from the wall, and Kate sprang up out of the heating duct with a triumphant grin, raising her hand for a celebratory high five. Reynie lifted his own hand—and instantly regretted it. The slap couldn’t have stung worse if it had been delivered by a passing motorcyclist. Cradling his palm against him like a wounded bird, he watched Kate reach back into the duct for Sticky, who was mumbling something about having melted. It took her a few tries—Sticky’s hands were so sweaty she couldn’t find a grip—but at last she caught him under the shoulders and slid him smoothly out of the duct like a loaf of bread from the oven.

Both of them appeared to have been baked, in fact. The heating duct must have been sweltering. Kate’s cheeks were brightly flushed, and her blond ponytail was damp and limp as a wrung mop. Sticky looked to have suffered even worse. His sweat-soaked clothes clung like a wet suit to his skinny frame; his light brown skin had gone a sickly shade of gray; and behind his wire-rimmed spectacles, which sat askew on his nose, his eyes seemed dazed and glassy. Beads of perspiration glistened like dewdrops on his smoothly shaven head.

“Hot,” Sticky said sluggishly. He blinked his eyes, trying to focus. “I am hot.”

“Tell me about it,” said Kate, already raising the window. “Why didn’t you two open this? Oh, I see, it won’t stay up. Well, we can just prop it with a book.” She reached toward the nearest shelf.

“Please don’t,” said Reynie, who was very protective of books. (When he had lived at Stonetown Orphanage, they had often been his only companions.) “That won’t be good for it—and if it fell out the window it’d be damaged for sure.”

“Okay, you’re right,” said Kate, sweeping her eyes round the room, “and there’s nothing else to use. Hang on, I’ll be right back.” And she disappeared into the heating duct as naturally as a seal slipping into water.

“She left her bucket in the other room,” rasped Sticky, adjusting his spectacles with slippery fingers and smudging them in the process. He tugged a polishing cloth from his shirt pocket. It was as damp as a baby wipe.

Constance was incredulous. “Kate left her precious bucket behind?”

“The duct is a tight fit,” Sticky said, resignedly poking the cloth back into his pocket. “The bucket would have made too much noise, and we didn’t want Rhonda to hear.”

Reynie smiled. He was reminded of their very first day in this house, almost a

year and a half ago now. Kate had squeezed through a heating duct then, too. He remembered her telling him how she’d tied her bucket to her feet and dragged it behind her, and how amazed he’d been by her account. It was strange to think he’d ever been surprised by Kate’s agility, or by the fact that she carried a red bucket with her wherever she went. Reynie had long since grown used to these things; they seemed perfectly normal to him now.

He was not at all startled, for instance, when Kate returned from her expedition in less time than it would have taken most people simply to walk down the hall. She emerged from the heating duct with a large horseshoe magnet—one of the several useful items she kept stored in her bucket—and in no time had stood it upright and propped open the window with it.

“That should stay,” Kate said with satisfaction, as wonderfully cool air drifted into the room, “but just to be sure…” From her pocket she produced a length of clear fishing twine, one end of which she tied to her magnet and the other to her wrist. “This way if the magnet slips I won’t have to fetch it later.”

All of this took Kate perhaps twenty seconds to accomplish. As soon as she’d finished, the children sat on the floor in a circle. It was pure habit. Anytime the four of them were alone they had a meeting. Together, privately, the children thought of themselves as the Mysterious Benedict Society, and as such they had held a great many meetings—some in extraordinarily dire circumstances.

“So what’s your team called?” asked Kate, twisting her legs into a pretzel-like configuration. “Sticky and I are the Winmates!” When this declaration met with baffled stares, she frowned. “Don’t you get it? It’s a play on words—a portly man’s toe, or… What did you say we call that, Sticky, when two words are kind of bundled together?”

“A portmanteau,” said Sticky.

“Right! A portmanteau! See, we’re called the Winmates because we’re inmates—like prison inmates, get it?—who win.” Kate looked back and forth at Reynie and Constance, searching their expressions for signs of delight.