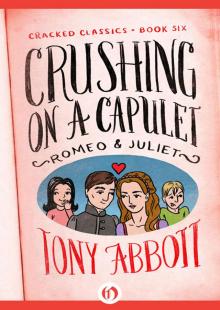

Crushing on a Capulet

Tony Abbott

Crushing on a Capulet

(Romeo & Juliet)

Tony Abbott

Chapter 1

“Ha, ha, ha!” I laughed as I stared at the door of Mr. Wexler’s classroom.

“Hey, Devin, it’s English class, not TV,” said my best-pal-even-though-she’s-a-girl, Frankie Lang, who just happened to walk up behind me. “What’s with all the laughing?”

Chuckling still, I pointed to a small sign taped to the classroom door and said, “Behold!”

The sign read PLAY IN THE CAFETERIA TODAY.

I smiled. “Frankie, our teacher has given us an assignment. We must play in the cafeteria!”

She nodded. “Wow … but why—”

“Never question such things!” I said sternly. “When teachers tell you to play, you play! This alone is good. But when they tell you to play in the cafeteria, which is where they keep the food, then, Frankie, the stars shine down on us, destiny is on our side, and school is good.”

“That was a beautiful speech, Devin,” she said. “And let me be the first to say that I approve of this new subject of ‘play.’ In fact, I’m thinking we should be in honors. We’d be excellent.”

“Then, let us go and excel,” I said happily, heading with my friend to the cafeteria.

Now, at Palmdale Middle School, where Frankie and I are sixth graders, we have one of these cafeterias that is also the auditorium. It has a stage at one end, with a big maroon curtain, a flagpole, and everything. Frankie and I like to sit on the edge of the stage to eat. Until the lunch ladies see us and chase us off.

Just as I was planning what sort of game we’d play, we rounded the corner and entered the caf. Right away, I knew something was wrong. Instead of a lot of playing going on, there was a lot of what looked like work.

First of all, everyone from our English class was hustling around, pushing the lunch tables aside and setting up chairs. Some kids were actually sweeping the floor.

“How are we supposed to play with all this work going on?” I asked.

“Beats me,” said Frankie.

“Ah! Frankie and Devin! You’re here!” called a voice.

We turned to see our teacher Mr. Wexler next to the stage, a small book in one hand, and a stack of weird, brightly colored clothes in the other.

“What’s with the pile of pajamas?” Frankie asked.

“They’re costumes,” our teacher replied dryly.

“Costumes?” I said, stepping back. “It’s not Halloween yet. Costumes for what?”

“For what, you ask?” He smiled largely, put the costumes down, handed the small book to Frankie, and using both hands, yanked open the curtain.

“Ta-da!” he chimed.

I gasped. On the stage were big wooden cutouts of crooked, old-style buildings. To the left were some pink-colored buildings, to the right were a bunch of blue ones. In between was a small open square with a fountain. Sticking up behind the buildings were several wobbly towers with banners hanging from them.

It looked like a scene from some old fairy tale.

Mr. Wexler took a deep breath, cleared his throat, then spoke loudly: “‘Two households, both alike in dignity—in fair Verona, where we lay our scene—from ancient grudge, break to new mutiny.…’”

He stopped.

We stared.

Finally, I spoke. “Mr. Wexler, the last time I checked, you were an English teacher. But you’re not talking English. You’re talking some other language. A weird one!”

He laughed. “No, no, Devin, it is English. In fact—it’s Shakespeare, William Shakespeare, one of England’s greatest playwrights. He’s the author of Romeo and Juliet, the play we’re putting on for the other classes today. Didn’t you see the sign on the classroom door?”

“That sign said ‘play in the cafeteria today,’” I said. “It means we’re supposed to play in the cafeteria.”

He shook his head. “No, it means we’re putting on a play in the cafeteria!”

“Then the sign wasn’t written in good English,” I said.

“Neither is this,” said Frankie, turning the book every which way. “The words are all crazy.”

Our teacher chuckled. “True, Frankie, the language is different. After all, the play was written over four hundred years ago. But you’ll see how the story comes alive when we perform it for the school on this stage today. These are some of the costumes our class will be wearing.”

He held up the pajamas again.

I frowned. “Mr. Wexler, you must be speaking that other language again, because it sounded like you said our class will be wearing funny clothes on stage—”

“Exactly,” said Mr. Wexler. “We’ve been reading Romeo and Juliet for the last week. So we’re all quite familiar with the parts … wait … don’t tell me you haven’t read the play?”

I turned to Frankie. She turned to me.

Reading. That was the problem. As good as Frankie and I were at the playing thing, we weren’t all that good at the reading thing. I’ve given this a lot of thought, and I think it has something to do with all the words they put in books. To get what’s going on, you’re supposed to read all of them. That’s the problem.

“Um … define read …” said Frankie.

Mr. Wexler gave out a big sigh. “Yes, yes, I can just imagine. You were probably too busy playing around to read the book I assigned.”

“Hey,” I said, “it’s what we’re good at.”

He made a face. “Well, in a nutshell, Romeo and Juliet are two young Italian people who fall in love—”

“Love?” I gasped. “Whoa! I thought school was supposed to be rated PG!”

Mr. Wexler laughed. “Oh, it’s a wonderful play, full of romance, of course, but full of action, too. It ends rather badly, of course. It’s one of Shakespeare’s tragedies.”

“It sounds pretty tragic,” I mumbled to Frankie.

Mr. Wexler pointed to a building on the stage that had an upstairs balcony overlooking a garden filled with painted bushes. “The balcony scene between Romeo and Juliet is one of the most famous scenes ever. Why, just listen to this wonderful poetry.…”

He gazed up at the balcony, extended his hand toward it, and launched into some pretty strange wordage.

“‘But soft,’” he muttered, “‘what light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun—’”

All of a sudden, someone came out onto the balcony. We gasped. It was a woman, but not a young Italian woman, if you know what I mean. She had grayish hair pulled up tight behind her head, and wore a bright flowery dress.

“Mrs. Figglehopper!” Frankie said.

It was Mrs. Figglehopper, our school librarian.

She looked down at Mr. Wexler, clasped her hands together, then spoke some wacky lines of her own.

“‘How camest thou hither, tell me? The orchard walls are high and hard to climb, and the place death, considering who thou art, if any of my kinsmen find thee here.’”

“‘With love’s light wings did I over-perch these walls,’” Mr. Wexler replied. “‘For stony limits cannot hold love out, and what love can do, that dares love attempt. Therefore thy kinsmen are no stop to me.…’”

Let me tell you, it was very weird watching our teacher and our librarian talk like that. I was pretty embarrassed for them, although they didn’t seem to be.

“Four hundred years old,” Frankie grumbled, still squinting at the book. “I guess people had more time on their hands back then. They needed it to figure out what the other people were saying!”

Mrs. Figglehopper tramped down the stairs from the balcony and came out on stage, full of chuckles.

“It’s not that hard to understand!” she boomed. “Besides, a good story is a good

story!”

“Quite right,” added Mr. Wexler. “In fact, Mrs. Figglehopper and I shall be in today’s play, too. Of course, not as Romeo and Juliet … oh, you know, I just had an idea.…”

He got a sudden weird look in his eye, and he moved that look over at me. “You know, Devin …”

“Uh-oh,” I said, backing away. “Here it comes.”

“Devin, performing in this play is the best way to learn it. If you want to do your best on our Romeo and Juliet test next week, you should probably play the part of Romeo.…”

I looked at my teacher. “I’m suddenly feeling faint. And I always faint at home. I’d better go there now—”

He blocked my way.

“And Frankie shall be Juliet!” said Mrs. Figglehopper, clasping her hands together again in delight.

Frankie gave the lady a gigantic frown. “Take that back, Mrs. F!” she said. “It’s not even funny!”

“Actually, even though it’s a tragedy, parts of Romeo and Juliet are quite funny,” said Mr. Wexler. “But, you’ll enjoy the whole thing more when you are both speaking your speeches on that stage.”

Frankie and I stared at each other, speechless.

“Good. It’s settled,” said Mrs. Figglehopper. “The PTA mothers have made costumes especially for your two roles. They’re in the library workroom. Would you toddle off and bring them here? Thank you.”

I was rooted to the floor in a kind of shock, still mumbling, “Me … play … on stage … lines … reading …”

Frankie was making a soft, whimpering sound. “Can’t do this … can’t do this … no, no, can’t do this …”

But the two grown-ups had no sympathy. They were cruel. They were heartless. And to make us move faster, they began talking wacky again.

“‘Arise, fair sun,’” said Mr. Wexler, “‘and kill the envious moon, who is already sick and pale with grief—’”

“Me, too,” I groaned. “Me, too.”

But my lament did no good.

Frankie and I had no choice but to stumble off sadly to the library.

Chapter 2

“Frankie, no way am I dressing up, PTA moms or no PTA moms,” I said, as we made our way down the hall to the library. “Dressing up includes the word ‘dress.’ And I don’t wear dresses!”

“Neither do I much,” she said, squinting at the book again. “But you gotta take a look at this stuff. The lines don’t even reach to the edge of the page.”

I peered at the pages. “Already, I have a headache. What do you even call that stuff?”

“Poetry, I think,” she said.

“Nuh-uh. Poetry is like ‘Roses are red, violets are blue, I like peanut butter, you like glue.’ This stuff is way too hard to understand. I predict we’ll flunk this play. Imagine me, failing play. Talk about tragedy!”

Frankie chuckled. “But you know, Devin, we’ve sort of been in this situation before. Faced with reading a classic old book and getting A’s on it anyhow.”

“Don’t go there,” I said, shivering.

But, of course I knew what she meant.

The zapper gates.

We pushed open the main library doors, took a sharp right, and entered the library workroom.

Frankie and I knew the place pretty well. It was a small room with tables pushed up against two walls. We saw a bunch of funny costumes on one table. On the other were stacks of old dusty books needing repair. There was a copy machine, a computer, a scanner, and a printer. And in the middle of the room were bookshelves with hundreds of old classic books that Mrs. Figglehopper was repairing.

But the most important—and crazy—things in the room were the zapper gates. That was what Mrs. Figglehopper called an old set of security gates that she stored in the library workroom.

I was staring at them now. They actually looked like a doorway, except that the sides only went up partway, and there was no top.

Frankie and I knew all about them. They’re the kind of gates that are supposed to go all zzzt-zzzt! when a book goes through them that hasn’t been checked out the right way.

But these gates don’t go all zzzt-zzzt!

They go kkkk-kkkk! And lightning flashes and thick, blue smoke fills the room and the wall behind the zapper gates cracks right open and you’re sucked into a book.

That’s right! Into a book!

It’s happened to Frankie and me a few times already! And each time it’s more incredible than the time before. We get all jumbled and tumbled around, then we get thrown out smack dab at the beginning of some old classic story—right there with the story’s real characters.

It is very weird and very impossible.

But being impossible doesn’t mean it’s not possible!

Okay, maybe it does. But it happens anyway!

“I can’t even read this!” said Frankie, shutting the book. “It’s like somebody is punishing my brain—but my brain didn’t do anything wrong!”

I laughed. “For sure. It usually doesn’t do anything at all—hey, look!”

Right next to the pile of funny costumes was a box full of T-shirts. The shirts had pictures of this old dude on the front, and they said SHAKESPEARE under the picture. “What are these? Prizes if we’re in the play?”

I pulled one on over my shirt. So did Frankie.

“Maybe if I could wear this, I might do a walk-on.”

She chuckled. “You’d have to walk on in tights,” she said, digging in the costume pile and holding up a pair of blue tights that were part of the Romeo outfit.

I stared at the wiggly things.

“Okay, this is where I check out. No way ever does Devin Bundy wear tights!” I started for the door.

“There’s also swords,” she said, holding up two bendy plastic toy swords that were next to the pile.

I stopped. “Swords? Mr. Wexler did say there was action in the play. And I like action toys.” I flashed one of the swords around in the air. “Okay, then. I choose to be a swashbuckling old-time dude. On guard, Miss Frankie of Lang!”

She grabbed the other sword and grinned. “Same to you, Sir Devin of Bundy!”

We started clacking our weapons all around the room, leaping up to the tabletops and waving our swords at each other.

“Now, this is the sort of play I can get into!” I said.

It was fun. But fun has a way of not lasting too long.

On a really great leap from the book table to Mrs. Figglehopper’s swivel chair, I accidentally lost my balance, fell back to the desk, and kicked the old Romeo and Juliet book clear across the room.

Yep, you guessed it. Right between the zapper gates.

Kkkkk!

The room exploded with bright blue light. The air shook, the floor quaked, Frankie and I tumbled to the floor, and the wall behind the gates cracked right open.

Instantly, thick, blue smoke poured from the crack.

“Oh, no!” I cried. “It’s happening!”

Before we could make a move—Hoop!—the book was gone. Vanished. Disappeared into the swirling, dark smoke of the cracked wall.

The next instant—floop! floop! floop!—the costumes were gone, wiggly tights and all.

“Did what just happened really happen?” I said.

“I think so. The PTA moms will be very mad.”

The library doors suddenly creaked open. Someone was coming toward the workroom.

“Frankie—we’ve got to get those costumes back!”

“And that book!”

“And we’d better do it right now!”

An instant later, Frankie and I were gone, too—floop! floop!—straight through the zapper gates and into the dark, swirling, smoky crack in the wall.

“Yikes!” cried Frankie.

“Yikes and a half!” I added.

Over and over we rolled. There were lots of legs and arms and costumes and props. It was like Frankie and I were inside some sort of classic-book clothes dryer, tumbling around and around until we were dumped down into a street in the p

ile of costumes.

I rolled over and over until I splatted against something flat and cold. Frankie slammed up against me. We both groaned for a while before we moved. When we got to our feet, we saw that all around us were old stone buildings and twisty streets. Some buildings were pink and some were blue.

In the center was an open square and a big stone fountain. But instead of spouting painted water, this one spouted actually real water.

“Frankie?” I said. “Do you see anything weird?”

“Devin, I don’t see anything not weird!”

“What I mean is, this looks a lot like the stage set in the cafeteria, only it’s really real. I think that’s weird.”

“Weird times two.” Frankie picked the book up from the ground and opened it to the first page. “Okay, look, first things first. The setting of the story. Mr. Wexler said Romeo and Juliet were Italian, right? Well, it says it right here, just like he told us, ‘In fair Verona where we lay our scene.’ So I guess we’re in Verona, Italy.”

“Isn’t Italy where all the meatballs are?”

She laughed. “With us here, there’s at least two.”

“Better make that four,” I said, pointing to the far side of the square. “Because here come a couple of guys wearing tights—”

Two men rushed into the square.

“They’re wearing swords, too,” said Frankie.

Spotting us instantly, the two tights-wearing men pulled out their deadly-looking swords and started running toward us, shouting something like “Get them!”

I turned to Frankie. “Can I just say something?”

“If you say it quick,” she said.

“It’s just one word,” I said. “HIDE!”

Chapter 3

But we couldn’t hide. The two swordy guys were all over us like sauce on meatballs, carving shapes in the air with their swords and backing us all the way up against the bubbly, spurting fountain.

“Whoa, dudes!” I shouted. “Put away the pointy things! This is the land of macaroni, not shish kebab!”

“Silence, you, you—Montague!” snarled one of the men, drawing shapes around my head with his sword. “Draw your blade and fight us!”

“It’s plastic!” I said, showing him how the toy sword bent every which way. “Besides, I’m not this Monty Glue you’re looking for. I’m Devin Bundy—”