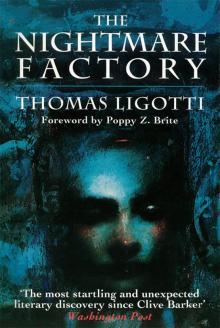

The Nightmare Factory

Thomas Ligotti

Thomas Ligotti was born in 1953 in Detroit, Michigan. One critic has written of his power as a storyteller: ‘It’s a skilled writer indeed who can suggest a horror so shocking that one is grateful it was kept offstage.’ His work has appeared regularly in a host of horror and fantasy magazines, earning him high esteem from followers of weird and macabre fiction everywhere. His previous books include Noctuary, Grimscribe: His Lives and Works and Songs of a Dead Dreamer

Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc.

260 Fifth Avenue

New York

NY 10001

First published in the UK by Robinson Publishing 1996

First Carroll & Graf edition 1996

Some of the stories in this collection first appeared in the following publications: Fantasy Tales, Dark Horizons, Eldritch Tales, Nyctalops, Grimwire, Weird Tales, Heroic Visions II, Grue, Crypt of Cthulhu, Fantasy Macabre, Dagon, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Tiamat, Tekelili! Fear All the Devils Are Here, Horror Mag, Deathrealm, The Urbanite, and A Whisper of Blood.

Stories from Songs of a Dead Dreamer copyright © Thomas Ligotti 1989

Stories from Grimscribe copyright © Thomas Ligotti 1991

Stories from Noctuary copyright © Thomas Ligotti 1994

Introduction and all stories in Part 4: Teatro Grottesco copyright © Thomas Ligotti 1996

Preface copyright © Poppy Z. Brite 1996

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 0-7867-0302-4

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Foreword by Poppy Z. Brite

Introduction: The Consolations of Horror

Part 1: from Songs of a Dead Dreamer

The Frolic

Les Fleurs

Alice’s Last Adventure

Dream of a Manikin

The Chymist

Drink to Me Only with Labyrinthine Eyes

Eye of the Lynx

The Christmas Eves of Aunt Elise

The Lost Art of Twilight

The Troubles of Dr. Thoss

Masquerade of a Dead Sword

Dr. Voke and Mr. Veech

Dr. Locrian’s Asylum

The Sect of the Idiot

The Greater Festival of Masks

The Music of the Moon

The Journal of J.P. Drapeau

Vastarien

Part 2: Grimscribe

The Last Feast of Harlequin

The Spectacles in the Drawer

Flowers of the Abyss

Nethescurial

The Dreaming in Nortown

The Mystics of Muelenburg

In the Shadow of Another World

The Cocoons

The Night School

The Glamour

The Library of Byzantium

Miss Plarr

The Shadow at the Bottom of the World

Part 3: from Noctuary

The Medusa

Conversations in a Dead Language

The Prodigy of Dreams

Mrs Rinaldi’s Angel

The Tsalal

Mad Night of Atonement

The Strange Design of Master Rignolo

The Voice in the Bones

Part 4: Teatro Grottesco and Other Tales

Teatro Grottesco

Severini

Gas Station Carnivals

The Bungalow House

The Clown Puppet

The Red Tower

FOREWORD

Poppy Z. Brite

Are you out there, Thomas Ligotti?

You have a lot to answer for, but I’ve never been able to discover anything of substance about you. That’s the way you seem to want it. Even in the single interview I managed to glean from the wasteland of the small press, you spoke exclusively about the craft of writing. Don’t mistake my meaning; there is no one I’d rather read upon the craft. But not a scrap of personal information escaped those lines of print. As someone who gives numerous, messy, highly personal interviews that I suspect I may yet live to regret, I wonder how you are able to do it.

I was twenty, on my first trip to San Francisco, when a friend first handed me your work Songs of a Dead Dreamer, the Silver Scarab limited edition with Harry O. Morris illustrations that approached the fabulousness of the stories. My interest was aroused at least partly by the fact that Ramsey Campbell, then and now one of my favourite writers, had seen fit to pen an introduction; so being asked to write this introduction has a certain poignancy.

Riding stoned in the back seat of a car across the Bay Bridge, I opened the book at random and read a sentence that will haunt me all my days, a sentence I’d give a thumb to have written:

We leave this behind in your capable hands, for in the black-foaming gutters and back alleys of paradise, in the dank windowless gloom of some galactic cellar, in the hollow pearly whorls found in sewerlike seas, in starless cities of insanity, and in their slums…my awe-struck little deer and I have gone frolicking.

from ‘The Frolic’

The glittering panorama of San Francisco, a city I already suspected of harbouring deep mystery from Fritz Leiber’s Our Lady of Darkness, became inextricably linked in my mind with this prose jewel. For me, those black-foaming gutters and back alleys (not to mention the Street of Wavering Peaks) will always be just across the bay from Berkeley.

Will you hate me if I confess that I photocopied the entire book? I’d promised to send it back to my friend, and I am no book thief. But I could not bear to part with your words, and I could not find another copy anywhere; those few precious copies had been snapped up and hoarded.

Songs of a Dead Dreamer has since been released by major publishers on at least two continents. I have three editions myself. But, until it was destroyed in a flood last year, I still had the looseleaf binder with that pathetic photocopy in it too.

I have followed your career since then—nearly a decade—and I still know nothing more of you than your fiction reveals. Though I know that fictional self-revelation can be considerable, I also know that it is frequently misinterpreted by the reader. If you were to call up and invite me over for coffee, I would expect to meet a slightly dissipated aesthete, sarcastic and decadent and wry, given to odd word-associations, with a taste not just for the macabre but for the truly, nakedly gruesome. (Let the critics blather on about subtle half-hidden horrors; you make me see it all.) But perhaps I would encounter someone else entirely. I suspect I’ll never know.

You have a lot to answer for, Thomas Ligotti. For every score of horrorheads who don’t ‘get’ your work, there will always be the one who is profoundly impressed and appalled by it, for it seems as though you have reached into his dreaming brain and pulled out the stuff of intensely private nightmares. I am one of those readers. Upon reading your stories, I often experience two distinct sensations: a faint déjà vu, not as if I’ve read the words before, but as if the images have already appeared somewhere in the murk of my subconscious; and a sense of Lovecraftian awe shading into existential nausea. More than any other author I can think of, you write decidedly weird fiction. And I can only marvel. Are you out there, Thomas Ligotti?

I believe I’ve just answered my own question.

INTRODUCTION:

THE CONSOLATIONS OF HORROR

Darkness, we welcome and embrace you

Horror, at least in its artistic presentations, can be a comfort. And, like any agent of enlightenment, it may even confer—if briefly—a sense of power, wisdom, and transcendence, especially if the conferee is a willing one with a true feeling for ancient mysteries and a true fear of the skul

lduggery which a willing heart usually senses in the unknown.

Clearly we (just the willing conferees, remember) want to know the worst, both about ourselves and the world. The oldest, possibly the only theme is that of forbidden knowledge. And no forbidden knowledge ever consoled its possessor. (Which is probably why it’s forbidden.) At best it is one of the more sardonic gifts bestowed upon the individual (for knowledge of the forbidden is first and foremost an individual ordeal). It is particularly forbidden because the mere possibility of such knowledge introduces a monstrous and perverse temptation to trade the quiet pleasures of mundane existence for the bright lights of alienage, doom, and, in some rare cases, eternal damnation.

So we not only wish to know the worst, but to experience it as well.

Hence that arena of artificial experience, supposedly of the worst kind—the horror story—where gruesome conspiracies may be trumped up to our soul’s satisfaction, where the deck is stacked with shivers, shocks, and dismembered hands for every player; and, most importantly, where one, at a safe distance, can come to grips (after a fashion) with death, pain, and loss in the, quote, real world, unquote.

But does it ever work the way we would like it to?

A test case

I am watching Night of the Living Dead. I see the ranks of the deceased reanimated by a double-edged marvel of the modern age (atomic radiation, I think. Or is it some wonder chemical which found its way into the water supply? And does this detail even matter?). I see a group of average, almost documentary types holed up in a house, fighting off wave after wave of hungry ghouls. I see the group hopelessly losing their ground and succumb each one of them to the same disease as their sleepwalking attackers: A husband tries to eat his wife (or is it mother tries to eat child?), a daughter stabs her father with a gardener’s trowel (or perhaps brother stabs sister with a bricklayer’s trowel). In any case, they all die, and horribly. This is the important thing.

When the movie is over, I am invigorated by the sense of having rung the ear-shattering changes of harrowing horror; I’ve got another bad one under my belt that will serve to bolster my nerves for whatever shocking days and nights are to come; I have, in a phrase, an expanded capacity for fear. I can really take it!

At the movies, that is.

The fearful truth is that all of the above brutalities can be “taken” only too well. And then, at some point, one starts to adopt unnatural strategies to ward off not the bogey but the sand man. Talking to the characters in a horror film, for instance: Hi, Mr. Decomposing Corpse lapping up a lump of sticky entrails, Hi! But even this tactic loses its charm after a while, especially if you’re watching some “shocker” by yourself and lack an accomplice to share your latest stage of jadedness and immunity to primitive fright. (At the movies, I mean. Otherwise you’re the same old vulnerable self.)

So after a devoted horror fan is stuffed to the gills, thoroughly sated and consequently bored—what does he (the he’s traditionally out-number the she’s here) do next? Haunt the emergency rooms of hospitals or the local morgues? Keep an eye out for bloody mishaps on the freeway? Become a war correspondent? But now the issue has been blatantly shifted to a completely different plane—from movies to life—and clearly it doesn’t belong there.

The one remedy for the horror addict’s problem seems this: that if the old measure of medicine is just not strong enough—increase the dosage! (This pharmaceutical parallel is ancient but apt.) And thus we have the well-known and very crude basis for the horror film’s history of ever-escalating scare tactics. Have you already seen such old classics as Werewolf of London too many times? Sample one of its gore-enriched, yet infinitely inferior versions of the early 1980s. Of course the relief is only temporary; one’s tolerance to the drug tends to increase. And looking down that long open road there appears to be no ultimate drugstore in sight, no final pharmacy where the horror hunger can be glutted on a sufficiently enormous dose, where the once insatiable addict may, at last, be laden with all the demonic dope there is, collapse with sated obesity into the shadows, and quietly gasp: “enough.”

The empty pit of boredom is ever renewing itself, while horror films become less tantalizing to the marginally sadistic movie-goer.

And what is the common rationale for justifying what would otherwise be considered a just barely frustrated case of sadomasochism? Now we remember: to present us with horrors inside the theater (or the books, let’s not forget those) and thereby help us to assimilate the horrors on the outside, and also to ready us for the Big One. This does sound reasonable, it sounds right and rational. But none of this has anything to do with these three R’s. We are in the great forest of fear, where you can’t fight real experiences of the worst with fake ones (no matter how well synchronized a symbolic correspondence they may have). When is the last time you heard of someone screaming himself awake from a nightmare, only to shrug it off with: “Yeah, but I’ve seen worse at the movies” (or read worse in the books; we’ll get to them)? Nothing is worse than that which happens personally to a person. And though a bad dream may momentarily register quite high on the fright meter, it is, realistically speaking, one of the less enduring, smaller time terrors a person is up against. Try drawing solace from your half-dozen viewings of the Texas Chain-Saw Massacre when they’re prepping you for brain surgery.

In all truth, frequenters of horror films are a jumpier, more casually hysterical class of person than most. We need the most reassurance that we can take it as well as anyone, and we tend to be the most complacent in thinking that seventeen straight nights of supernatural-psycho films is good for the nerves and will give us a special power which non-horror-fanatics don’t have. After all, this is supposed to be a major psychological selling point of the horror racket, the first among its consolations.

It is undoubtedly the first consolation, but it’s also a false one.

Interlude: so long, consolations of mayhem

Perhaps it was a mistake selecting Night of the Living Dead to illustrate the consolations of horror. As a delegate from Horror-land this film is admirably incorruptible, oozing integrity. It hasn’t sold out to the kindergarten moral codes of most “modern horror” movies and it has no particular message to deliver: its only news is nightmare. For pure brain-chomping, nerve-chewing, sight-cursing insanity, this is a very effective work, at least the first couple of times or so. It neither tries nor pretends to be anything beyond that. (And as we have already found, nothing exists beyond that anyway, except more and more of that.) But the big trouble is that sometimes we forget how much more can be done in horror movies (books too!) than that. We sometimes forget that supernatural stories—and this is a very good time to boot nonsupernatural ones right off the train: psycho, suspense, and the like—are capable of all the functions and feelings of real stories. For the supernatural can serve as a trusty vehicle for careening into realms where the Strange and the Familiar charge each other with the opposing poles of their passion.

The Haunting, for example. Besides being the greatest haunted house film ever made, it is also a great haunted human one. In it the ancient spirit of mortal tragedy passes easily through walls dividing the mysteries of the mundane world from those of the extra-mundane. And this supertragic specter never comes to rest in either one of these worlds; it never lingers long enough to give us forbidden knowledge of either the stars or ourselves, or anything else for that matter. To what extent may the “derangement of Hill House” (Dr. Markway’s diagnosis) be blamed on the derangement of the people who were, are, and probably will be in it? And vice versa of course. Is there something wrong with that spiral staircase in the library or just with the clumsy persons who try to climb it? The only safe bet is that something is wrong, wherever the wrongness lies…and lies and lies. Our poor quartet of spook-chasers—Dr. Markway, Theo, Luke, and Eleanor—are not only helpless to untie themselves from entangling puppet strings; they can’t even find the knots!

The ghosts at Hill House always remain unseen, except i

n their effects: savagely pummeling enormous oak doors, bending them like cardboard; writing assonant messages on walls (“Help Eleanor come home”) with an unspecified substance (“Chalk,” says Luke. “Or something like chalk,” corrects Markway); and in general giving the place a very bad feeling. We’re not even sure who the ghosts are, or rather were. The pious and demented Hugh Crane, who built Hill House? His spinster daughter Abigail, who wasted away in Hill House? Her neglectful companion, who hung herself in Hill House? None of them emerges as a discrete, clearly definable haunter of the old mansion. Instead we have an undefined presence which seems a sort of melting pot of deranged forces from the past, an anti-America where the very poorest in spirit settle and stagnate and lose themselves in a massive and insane spectral body.

Easier to identify are the personal specters of the living, at least for the viewer. But the characters in the film are too busy with outside things to look inside one another’s houses, or even their own. Dr. Markway doesn’t acknowledge Eleanor’s spooks. (She loves him, hopelessly.) Eleanor can’t see Theo’s spooks (she’s lesbian) and Theo avoids dwelling on her own. (“And what are you afraid of, Theo?” asks Eleanor. “Of knowing what I really want,” she replies, somewhat uncandidly.) Best of all, though, is Luke, who doesn’t think there even are any spooks, until near the end of the film when this affable fun-seeker gains an excruciating sense of the alienation, perversity, and strangeness of the world around him. “It should be burned to the ground,” he says of the high-priced house he is to inherit, “and the earth sown with salt.” This quasi-biblical quote indicates that more than a few doors have been kicked down in Luke’s private passageways. He knows now! Poor Eleanor, of course, has been claimed by the house as one of its lonely, faceless citizens of eternity. It is her voice that gets to deliver the reverberant last lines of the film: “Hill House has stood for eighty years and will probably stand for eighty more…and we who walk there, walk alone.” With these words the viewer glimpses a realm of unimaginable pain and horror, an unfathomable region of aching Gothic turmoil, a weird nevermoresville.