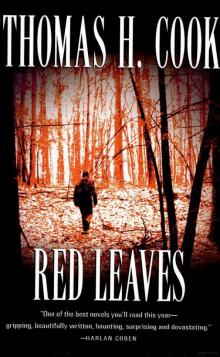

Red Leaves

Thomas H. Cook

Red Leaves

Thomas H. Cook

From Publishers Weekly

In this affecting, if oddly flat, crime novel from Edgar-winner Cook (The Chatham School Affair), Eric Moore, a prosperous businessman, watches his safe, solid world disintegrate. When eight-year-old Amy Giordano, whom Eric's teenage son, Keith, was babysitting, disappears from her family's house, many believe Keith is an obvious suspect, and not even his parents are completely convinced that he wasn't somehow involved. As time passes without Amy being found, a corrosive suspicion seeps into every aspect of Eric's life. That suspicion is fed by Eric's shaky family history-a father whose failed plans led from moderate wealth to near penury, an alcoholic older brother who's never amounted to much, a younger sister fatally stricken with a brain tumor and a mother driven to suicide. Not even Eric's loving wife, Meredith, is immune from his doubts as he begins to examine and re-examine every aspect of his life. The ongoing police investigation and the anguish of the missing girl's father provide periodic goads as Eric's futile attempts to allay his own misgivings seem only to lead him into more desperate straits. The totally unexpected resolution is both shocking and perfectly apt.

From Booklist

Cook's latest is proof that he is maturing into a gifted storyteller. An eight-year-old girl is missing. The police quickly zero in on her baby-sitter, Keith Moore. Keith's parents proclaim his innocence, but his father, Eric, has his own secret doubts. The way the author tells the story, it really doesn't matter whether Keith is guilty or not; what matters is the way the Moore family slowly disintegrates, as his parents deal in their own ways with the possibility that their son may be a monster. The novel is narrated by Eric; perhaps the story might have been slightly more effective if it were told in the third person, so we could watch Eric fall apart (rather than listen to him tell us about it), but that's nit-picking. In terms of its emotional depth and carefully drawn characters, this is one of Cook's best novels.

Red Leaves

Thomas H. Cook

AN OTTO PENZLER BOOK

A HARVEST BOOK • HARCOURT, INC.

Orlando Austin New York San Diego Toronto London

Copyright © 2005 by Thomas H. Cook

All rights reserved.

For Susan Terner,

courage under fire

Oh, return to zero, the master said.

Use what's lying around the house.

Make it simple and sad.

—STEPHEN DUNN, "Visiting the Master"

PART I

When you remember those times, they return to you in a series of photographs. You see Meredith on the day you married her. You are standing outside the courthouse on a bright spring day. She is wearing a white dress and she stands beside you with her hand in your arm. A white corsage is pinned to her dress. You gaze at each other rather than the camera. Your eyes sparkle and the air around you is dancing.

Then there are the brief vacations before Keith was born. You are in a raft on the Colorado River, sprayed with white water. There you are, nearly blinded by the autumn foliage of New Hampshire. On the observation deck of the Empire State Building, you mug for the camera, feet spread, fists pressed to waists, like masters of the universe. You are twenty-four and she is twenty-one, and there is something gloriously confident in the way you stand together, sure and almost cocky. More than anything, without fear. Love, you have decided by then, is a form of armor.

Keith appears first in the crook of Meredith's right arm. She is lying in a hospital bed, her face bathed in sweat, her hair in disarray. Keith's small body floats in a swirl of bedding. His face is in profile, and a tiny pink hand instinctively reaches for something his closed eyes cannot see, his mother's loosely covered breast. Meredith is laughing at this gesture, but you recall that she was clearly struck by it, too, thought it a sign of high intelligence or early adventurousness, ambition, the drive to make a mark. You reminded her, joking, that her son was only a few minutes old. Yes, yes, of course, she said.

Here he is at two, unsteady on his feet, toddling toward the stuffed bear your brother, Warren, gave him that Christmas. Warren sits on the sofa, beside Meredith. He is leaning forward, his large pudgy hands blurred because he was clapping when you took the picture, clapping hard and fast, urging Keith forward like a good wind at his back. So lucky, Bro, he will say to you at the door before he leaves, so lucky to have all this.

You often pose before all you have. You stand with Meredith and Keith, who is six now and holds a plastic Wiffle ball bat. You are in front of the little house on Cranberry Way. You bought it on the slimmest of financial credentials, and Meredith predicted the loan would not be approved, and so, when it was, you uncorked a bottle of inexpensive champagne and toasted your new status as homeowners. There's the picture, you and Meredith with glasses raised, Keith standing between you, his six-year-old hand lifted in imitation, holding a glass of apple juice.

You build a business, buy a second, larger, house on a more secluded lot. In that larger house the holidays come and go. You carve turkey and hang ornaments on real trees, then later, fearing fire, on artificial ones. In photographs you wallow in holiday gift wrapping, and as the years pass, the pictures show your face aglow in the light of many birthday candles.

You buy Meredith a ring on your fifteenth anniversary and with Keith and Warren watching, you marry her again, this time writing your own vows. That night, in the bed's comforting darkness, she tells you that she has never stopped loving you, and it is all you can do not to weep.

You buy your son a simple, inexpensive bike for his tenth birthday, then an elaborate twelve-speed when he turns fourteen. He's not particularly mechanical, so you spend some time showing him the gears. After a while, you ask him if he'd prefer a less-complicated bike. He says he would, but that it has nothing to do with the gears. He prefers everything less complicated, he tells you, and the look in his eyes when he says this suggests that there may be hidden depths in him, unexpected complexities. You say nothing of this, however, but later you wonder if your son, the one who'd once rested so securely in the crook of Meredith's arm, has now begun to emerge from the comfortable cocoon you have so carefully woven around him. If so, you are pleased, and you are suns Meredith will be pleased.

Another year passes. Keith is almost as tall as you are, and Meredith has never looked more radiant. A warm satisfaction settles over you, and you realize that it isn't the house or the business that fills you with a sense of accomplishment, ft is your family, the depth and balance it has given to your life, a quiet rootedness and sense of well-being your father never attained and which, for some reason at the end of that summer, you recognize as the crowning victory of your life.

And so you decide to take a photograph. You set up the tripod and call Keith and Meredith outside. You take your place between them, one arm over your son, the other over your wife. You have timed the camera. You see the warning light and draw them close in beside you. Ready now, you tell them—smile.

ONE

Family photos always lie.

That's what occurred to me when I left my house that final afternoon, and so I took only two.

The first was of my earliest family, when I was a son, rather than a father. In the picture, I am standing with my mother and father, along with my older brother, Warren, and my younger sister, Jenny. I am smiling, happy because I've just been accepted to a prestigious private day school. But the other smiles now strike me as false, because even then there must have been fissures in the unruffled happiness they convey, beasts lurking just beyond the firelight.

By the end of that summer, for example, my father must have known that years of bad investments and extravagant spending had surely caught up with him, that bankruptcy and its accompanying humiliations were on

ly a few short months away. I doubt, however, that he could have envisioned the full bleakness of his final years, the retirement home where he would sit hour upon hour, peering through the lace curtains, thinking of the grand house in which we'd all once lived, another asset lost.

Despite all this, or maybe because of it, my father meets the camera with a broad and oddly blustering grin, as if the old man felt his smile could protect him from the horde of angry creditors that was already gathering for a final assault. My mother's smile is more tentative—weak, hesitant, like a translucent mask beneath which her true face, though blurred, is yet still visible. It is an effortful smile, the corners of her mouth lifted like heavy weights, and had I been less self-absorbed, I might have noticed its tentativeness earlier, perhaps in time to have asked the question that later repeated so insistently in my mind, What is going on in you?

But I never asked, and so the day her car went flying off Van Cortland Bridge, it never occurred to me that anything might have been on her mind other than what she planned to cook for dinner or the laundry she'd left neatly folded on all our beds that afternoon.

My brother, Warren, stands sloppily to my left. He is only fifteen, but his hair is already thinning and his belly is wide and round and droops over his belt. Even at that age, he looks curiously past his prime. He is smiling, of course, and there is no hint of any reason why he shouldn't be, though I later had to wonder what fears might even then have begun to surface, the sense that certain already-planted seeds would bear grim fruit.

Finally, there is Jenny, so beautiful that even at seven she turned heads when she came into a room. Adorable, Warren always called her. He'd stroke her hair or sometimes simply look at her admiringly. Adorable, he'd say. And she was. But she was also quick and knowing, a little girl who came home from her first day at school and asked me why it was necessary for the teacher to repeat things. I told her it was because some people couldn't get it the first time. She took this in for a moment, thinking quietly, as if trying to incorporate nature's inequality within the scheme of things, calculate its human toll. "How sad," she said finally, lifting those sea blue eyes toward me, "because it's not their fault."

In this particular photograph Jenny's smile is wide and unencumbered, though in all the photographs after this one the cloud is clearly visible, the knowledge that it has already taken root in that fantastic brain of hers, microscopic at first, then no larger than a pinpoint, but growing steadily, taking things from her as it grew, her balance, her ringing speech, everything but her beauty, before it took her life.

She was the one I most often thought about after leaving my house that last afternoon. I don't know why, save that I suspected she might be able to understand things better than I could, and so I wanted to go over it all with her, trace the burning fuse, its series of explosions, seek her celestial wisdom, ask her, Do you think it had to end this way, Jenny, or might the damage have been avoided the dead ones saved?

The evening of that final death, he said, "I'll be back before the news." Meaning, I suppose, the network news, which meant that he would be home before six-thirty. There was no hint of the ominous in what he said, or of anything sinister, no sense at all that the center had collapsed.

When I recall that day, I think of my second family, the one in which I am husband to Meredith and father to Keith, and I wonder what I might have said or done to stop the red tide that overwhelmed us. That's when I see another picture, this one of a little girl from another family, a school photograph used in a hastily distributed flyer, the little girl smiling happily below the cold black words: MISSING.

Amy Giordano.

She was the only daughter of Vince and Karen Giordano. Vince owned a modest produce market just outside the town limits. It was called Vincent's Fresh Food, and Vince dressed himself as a walking advertisement for the place. He wore green flannel pants, a green vest, and a green cap, the latter two articles festooned with the name of the store. He was a short muscular man with the look of a high school wrestler who'd let himself go, and the last time I saw him—before the night Keith left for his house—he was carrying a brown paper bag with six rolls of film. "My brother's family came for a week," he explained as he handed me the bag, "and his wife, she's a camera nut."

I owned a small camera and photo shop in the town's only strip mall, and the pictures Vincent Giordano left that afternoon showed two families, one large, with at least four children ranging in age from approximately four to twelve, and which had to have belonged to the visiting brother and his "camera nut" wife. The other family was small, a circle of three—Vince, his wife, Karen, and Amy, their only daughter.

In the pictures, the two families present themselves in poses that anyone who develops family photos taken at the end of summer in a small coastal town would expect. They are lounging in lawn chairs or huddled around outdoor tables, eating burgers and hotdogs. Sometimes they sprawl on brightly colored beach towels or stand on the gangway of chartered fishing boats. They smile and seem happy and give every indication that they have nothing to hide.

I have since calculated that Vincent dropped off his six rolls of film during the last week of August, less than a month before that fateful Friday evening when he and Karen went out to dinner. Just the two of them, as he later told police. Just the two of them ... without Amy.

Amy always reminded me of Jenny. And it was more than her looks, the long wavy hair I saw in her family photos, the deep-blue eyes and luminous white skin. Certainly Amy was beautiful, as Jenny had been beautiful. But in the photographs there is a similar sense of intuitiveness. You looked into Amy's eyes and you thought that she saw—as Jenny did—everything. To reporters, Detective Peak described her as "very bright and lively," but she was more than that. She had Jenny's way of peering at things for a long time, as if studying their structures. She did this the last time I saw her. On that September afternoon, Karen had brought in yet another few rolls of film, and while I wrote up the order, Amy moved about the store, carefully examining what she found there, the small, mostly digital, cameras I stocked, along with various lenses, light meters, and carrying cases. At one point she picked up one of the cameras and turned it over in her small white hands. It was an arresting scene, this beautiful child lost in thoughtful examination, silent, curiously intense, probing. Watching her, I had a sense that she was studying the camera's various mechanisms, its buttons and switches and dials. Most kids start by merely snapping pictures and grinning playfully, but the look on Amy's face was the look of a scientist or technician, an observer of materials and mechanical functions. She didn't want to take a picture; she wanted to discover how it was done.

"She was so special," Karen Giordano told reporters, words often used by parents to describe their children. As a description it is usually exaggerated, since the vast majority of children are not special at all, save in the eyes of those who love them. But that doesn't matter. What matters is that she was Karen Giordano's daughter. And so on those days when I make my way down the village street, noting faces that from high above might appear indistinguishable as grains of sand, I accept the notion that to someone down here, someone close up, each face is unique. It is a mother's face or a father's; a sister's or a brother's; a daughter's or a son's. It is a face upon which a thousand memories have been etched and so it is differentiated from every other face. This is the core of all attachment, the quality that makes us human, and if we did not have it we would swim forever in an indifferent sea, glassy-eyed and unknowing, seeking only the most basic sustenance. We would know the pain of teeth in our flesh and the stinging scrape of rocks and coral. But we would know nothing of devotion and thus nothing of Karen Giordano's anguish, the full measure of feeling that was hers, the irreparable harm and irrevocable loss, the agony and violence that lay secreted, as we all would come to learn, within a simple promise to be home before the news.

TWO

There was little rain that summer, and so when I heard the rumble of thunder, I looked up

but saw nothing more threatening than a few high clouds, torn and ragged, pale brushstrokes across the blue.

"Heat lightning," I said.

Meredith nodded from her place in the hammock, but kept her attention on the magazine she was reading. "By the way," she said, "I have a departmental meeting tonight."

"On a Friday?" I asked.

She shrugged. "My thought, exactly, but Dr. Mays says we have to take a look at the year ahead. Make sure we understand our goals, that sort of thing."

For the last eight years, Meredith had taught in the English department of the local junior college. For most of that time, she'd served as a lowly adjunct. Then suddenly, death had opened a full-time position, and since then, she'd assumed more and more administrative duties, gone off on professional days and attended seminars in Boston and New York. She had grown more confident and self-assured with each added responsibility, and when I think of her now, it seems to me that she had never appeared happier than she did that evening, relaxed and unburdened, a woman who'd found the balance of family and career that best suited her.

"I should be home by ten," she said.

I was standing at the brick grill I'd built four summers before, an unnecessarily massive structure I enjoyed showing off for the loving craft I'd employed while building it. There were brick curves and brick steps and little brick shelves, and I loved the sheer solidity of it, the way it would hold up against even the strongest storm. I'd also loved every aspect of the work, the thick, wet feel of the mortar and the heaviness of the brick. There was nothing flimsy about it, nothing frail or tentative or collapsible. It was, Meredith later told me, a metaphor not for how things were, but for how I wanted them, everything lined up evenly, made of materials that were sturdy and unbending, built to last.