Women and Men

Thomas Berger

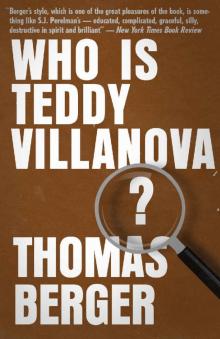

Who Is Teddy Villanova?

Thomas Berger

Copyright

Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 1008

New York, NY 10016

www.DiversionBooks.com

Copyright © 1977, renewed 2005 by Thomas Berger

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

For more information, email [email protected]

First Diversion Books edition July 2016

ISBN: 978-1-68230-692-5

Also by Thomas Berger

Crazy in Berlin

Reinhart in Love

Little Big Man

Killing Time

Vital Parts

Regiment Of Women

Sneaky People

Who Is Teddy Villanova?

Arthur Rex: A Legendary Novel

Neighbors

Reinhart’s Women

The Feud

Nowhere

Being Invisible

The Houseguest

Changing The Past

Orrie’s Story

Meeting Evil

Robert Crews

Suspects

Return of Little Big Man

Best Friends

Adventures of the Artificial Woman

Abnormal Occurrences

Table of Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

More from Thomas Berger

Connect with Diversion Books

To Charles Rydell and Colline du Vent

We are all celebrating some funeral.

—Baudelaire,

“On the Heroism of Modern Life”

1

Call me Russel Wren. A secretary named Peggy Tumulty was my unique employee, and at the moment I owed her a fortnight’s pay. In arrears on the rent for my apartment, on the door of which the churlish super had posted a notice that tended to humiliate (and which, ripped away, was soon reborn in more blatant advertisement), I had lately, stealthily, moved, auxiliary underwear and socks in an ex-Downy carton, into my office.

For another ten days I was a tenant in good standing in the five-story structure of superimposed lofts on East Twenty-third Street, where my neighbors were little novelty firms, agencies for obscure services, and, in the second-floor rear, an after-hours social club for persons of Mediterranean mien and attire.

I was an unlicensed private investigator, but I possessed an unlicensed firearm, a tiny Browning automatic in .25 caliber (pressed upon me once, and then forgotten, by a client who, suspecting his wife had taken a lover, had worked a ruse-suicide attempt that, owing to a hair-trigger, had cost him an earlobe). I keep this pistol in hiding; against any arm more formidable than a penknife it would be outweaponed; and in New York, defending oneself against attack not only is in heinous violation of innumerable ordinances but might well provoke the frustrated assailant to bring a successful suit for damages.

Finally, before we make a flying cannon ball into the murky waters of this narrative, I should say I am a bachelor of thirty (but heterosexual, as some have said, to the threshold of satyriasis). I took a B.A. and M.A. amidst the thronged anonymity of State, thereafter served at the same institution, for a niggardly wage, as instructor in English; was released as redundant and tried to write a play; and after having been photographed in intimate conversation with someone else’s wife, was given employment by the private investigator, himself a grandfather, as cameraman as well as technical adviser on contemporary illicitness. Eventually he turned over to me the transom department of his business, going himself into the more lucrative assignments in the detection of shoplifting. I opened my own agency a year later.

I was metaphorically on my uppers, though literally dozing at my desk, on that late-April morning when Peggy signaled me by interoffice buzzer. My latest job had ended two weeks earlier. Crying “Room Service!” I had induced a married man to open the door of a hotel room for which he had registered under a false name with a woman not his wife. His legal spouse was my client. I was alone, not needing a friendly witness, because the wife wanted me at this time only to serve as a threat to his composure and not to collect evidence for litigation.

In this assignment I failed. He was a short and slight-built man—a figure very common among satyrs, incidentally—but could laugh as robustly as a worthy of twice his bulk. Lowering his chin at last—he had been guffawing at the chandelier, a hippodrome for silverfish—he said: “Tell Gretta that it isn’t Gertrude.” He repaired into the bath room, could be heard mumbling, and soon brought out a remarkably obese woman, nude above but toweled below the navel. “Speak your piece,” said the man. In a voice of thin timbre, suggesting Shylock’s “squeaking of the wry-neck’d fife,” she said: “I’m a prostitute.”

“That was Gertrude all right all right,” said Gretta, when I delivered my report. For this job of work I received $100. Easily earned, no doubt, but it represented my entire income thus far in April.

It had been so long since I last heard Peggy’s signal that it quite startled me now: I came to full life with a scowl and a shudder. To ask about her wages Peggy would waylay me if I passed through the outer office; for this reason I tended more and more to stay holed up until she went home at five, not seeing her person all day. For routine communications—arrival, lunchtime, departure—she cracked my door an inch and shouted in, though the strident voice she assumed for such a purpose was a squander of energy, as was opening the door, given the thin plywood that divided my half-loft into two rooms.

Since I had set up housekeeping in the inner office (performing my toilet at the deep washbasin that I had inherited from the predecessor photographic lab; mixing my freeze-dried Taster’s Choice and Cup-a-Soup with hot water from the tap, which owing to the rust of vintage plumbing drooled already dark as beef broth from a degenerated rubber aerator fixed on its nose, a device I suffered to remain because I could not bear to touch it), Peggy had never penetrated that space. She was twenty-nine, a Queens Irish spinster of the type I should call relentless, and unless she had lost her fleur while competing in the high hurdles as a parochial schoolgirl, she was yet in formidable possession of it. My theory was that Peggy believed her entering my chamber might be construed as a suggestion, even though she carried a file of unpaid bills, that in reciprocation the temple of her body might be invaded.

Peggy had an elaborate pair of breasts, but quite near and flanking them were always, even on winter days when the heat invariably fled the corroded old radiators, crescents of sweat stains in the armpits of the oysterish or pale-beige blouses she doggedly favored. She had rather more ample hips than those that attract me most, yet a slacker behind, and withal plump calves, notwithstanding which she wore skirts which cleared the knee. Only under certain freakish conditions of light could her hair be seen as not absolutely black. I dote on pale blondes.

Her voice was off-putting as well. When she raised it she could loosen the hardened putty from the window-panes, and though sexually a prude she was coarsely candid about truly impolite functions. “Got to hit the can!” was her shout as preface to a visit down the hall, if indeed her name for

that facility had justice: toilet, basin, and unshaded light bulb, the door unmarked as to sex and usually left unlocked by the denizens of the rear loft, who, I suspected from the name of their operation, The Ganymede Press, printed pornography of the pederast persuasion. Winos sometimes found their way to the water closet and went peacefully to earth within—until routed by Peggy’s howl: she was self-righteously fearless at such encounters.

Back, finally, to her summons. The phone company’s intercom arrangement was, like all the offerings of that extortive monopoly, too expensive. We had our homemade rig—Peggy’s work, actually; I am maladroit with pliers: a little push button on her desk was connected to a long wire that traveled, stapled intermittently, over hill and dale and windy moor, I mean under the door, along the base of the wall and then, turning at right angles, straight across the carpetless floor and up the back wall of my desk to a buzzer half the size of a cigarette package and powered by two penlight dry cells.

At the sound I picked up Ma Bell’s jet-black baby from its cradle, a simple extension from the one on Peg’s desk.

“Are you free?” she asked, and when I responded without chaff—I never wisecrack with Peggy when I owe her money—she said: “Will you see a Mr. Bakewell?”

She was bright enough to turn away bill collectors without consulting me; therefore I asked for two minutes, and put my dirty coffee cup in a drawer and scraped the English muffin crusts and crumbs into the waste can.

I was on the point of entering the noose of an already knotted tie when I realized I was wearing a soft knitted shirt of Ban-Lon. The blue hand-towel hanging from the lip of the washbasin was damp but of too dark a dye to show dirt. I swung its clamminess around my neck and fashioned it into a makeshift cravat. I found my tan corduroy jacket and punched into it; even when new that garment had an abused look, but worn with an insolent carriage it would, I hoped, escape the downright crestfallen. Finally, I seized from the couch the Indian blanket under which I had slept the night, its fringes up my nostrils, and pitched it behind the waist-high trap door of a disused dumbwaiter, the little rising stage of which had fortunately last halted, and frozen there, at my level: it served as the only closet in either room.

I limped, my left thigh exuding the pins & needles it had collected during my doze, to the door, which I opened as deliberately as, given my hunger for a client, I could, and saw Mr. Bakewell seated on both the camp chairs which with Peggy’s desk comprised the furniture of the outer office. At least I saw him: the chairs had to be assumed to be supporting his vast body, as he occupied the place where they had been, and he was in the position of sitting. I estimated his weight as a good 300 and, when he rose, adjusted this upwards. I am, with expanded chest and rigidifled tendons, just, or at any rate not far from, five feet ten. He must have risen to six-six or -seven, and as he plowed towards me, as if wading through knee-high slush, I feared he would never negotiate the entrance to my inner office, which was of both a height and width somewhat less generous than the standard, owing to my having taken the advice, as usual to my detriment, of Sam Polidor, my landlord, and hired for its fitting the building-super, an ancient winesoak, so feeble he could scarcely lift a saw let alone cut steadily with it. Though no cabinetmaker, Peggy took over finally and got the thing to hang in approximate agreement with the jamb, if to do so the former had to be reduced in longitude by three inches, in width by four.

“Good morning, sir,” I chirped, stepping through with dipped shoulder and torsioned trunk—and my current weight was 157 in anklets and smallclothes. “My officesess being remodeled,” I added in an anxious lisp. “Shall we converse in the corridor?”

I took a step towards the outside door, to dramatize my suggestion, and then quickly took another to avoid being humorously, inexorably trampled into the scarred old floor boards. So distracted, I did not see the maneuver by which, incredibly, he passed through the strait gate of the inner room, but it must have been as marvelous as the glide of rich men into heaven. When I turned back I could see nothing through the frame but an expanse of suit: this was all the more remarkable in that he was actually some distance from the door. As it happened I scraped my head on my own entry.

He spun about to face me, in as swift and deft a movement as that by which he must have cleared the doorway. I had not yet had time to react to his visage, which was appropriately large, but also, in its upper half, unexpectedly delicate. He had especially lustrous eyes, long-lashed, almost girlish, and a nose of sensitive modeling. But his mouth was small and mean and set above jaws that came forward from behind flat ears to join in a dimple the lobes of which were as big as baby’s kneecaps.

He spoke in a singular manner, scarcely opening his oral aperture; yet I suspected, from the swelling above and below, that his upper row of teeth was nowhere near the lower; that is to say, not in the malocclusion of the “tough” style of address, but in the uncertain suspension of poorly fitted dentures. It was impossible for me to estimate the age of a man that large.

“Oorillpuh—” he began, and then, confirming my suspicion, probed his mouth with a parsnip-finger, and started again with a clarified version of the same phrase: “You little punk—”

He employed his massive hand once more, now not for the resituation of his dental plate but, formed into the claw of an earth mover, to grasp the entire bosom of my knitted shirt, which had it not been of elastic synthetic would thereby have been ripped from my quailing chest, revealing the grayed but recently laundered T-shirt beneath. That the latter clung to my skin despite his grasp suggested either the surgical delicacy of his fingers or the imprecision of his rage: it was yet too early to determine whether he intended to hurt, or merely to warn, me; and naturally I clung to a hope for the milder, despite a profound, probably masochistic conviction that favored the worse.

I had fenced some in college: if I could get down the hall to the toilet, where a filthy old mop was cached, I might fend Bakewell off with its splintery handle. As an idea this was much less farcical than one would be in which I designed an attack on him with my bare paws. Speaking of bear paws, he had now lifted his other one, clenched, to a position near the tremendous boss of his right shoulder cap.

I had probably been uttering unarticulated sounds of dismay—someone was gasping and grunting—but now, though no less desperate, I managed to deliver a statement so banally reasonable it could not but assume the form of a cliché.

“I don’t know you from Adam.”

Nevertheless his fist, having reached the limit of its upward travel, came forward. The movement, however, was as yet oleaginously slow, quite unlike his mode of slipping through constricted doorways. He was therefore a complex man. And, understanding that, I believed I was no longer unarmed.

“Very well,” I said, throwing my opened palms colateral with my hips, shrugging to the extent allowed by the taut Ban-Lon. “Ill take my punishment. Then perhaps you’ll tell me what it was for.”

I was wrong about his complexity, at least in this regard. He took me simply at my word. The bludgeon of his balled hand continued towards me until it obliterated the world. An instant of darkness, then one of brilliance, though I felt the actual impact not at all. I had no consciousness of my backward velocity. When I saw him next, he was yet where he had been, but the edge of the couch seat was fitted neatly into the small of my back, my nape was against the rear pillows, and my knees were just off the floor, with my calves and feet compressed precisely, painfully, between.

He had struck me in the forehead, that helmet of protective bone, an impractical stroke even for such stout fingers as his, had he not turned his hand on edge and presented to my skull the resilient karate blade that swells out between the base of the smallest digit and the wrist: in his case, the size and consistency of the fleshy side of a loin of pork.

He continued to loom there while, shaking my head, I put my vision, which for a moment was as if through shattered glass, in order. I was pleased that the first punch, whether by design or poor co

ordination, had been relatively harmless, but I could not count on receiving a succession of such favors—not that this hammer blow was utterly undamaging, for that matter: the surf surged regularly in my ears and in the intervals of its ebbing left me with a throatful of wet sand. My loafers were in a position just ahead of his coal-barge brogans, a yard from where I slumped; meanwhile, my feet, twisted on their edges and crushed under the crease between thigh and buttock, were only stockinged: he had knocked me out of my shoes!

I should have liked to learn to walk erect again by stages, beginning with the infantile, but suspecting his next assault might catch me with his foot in my mouth, I instead drew myself warily up the face of the couch and when my rump reached the level of the seat, shot it back. My hips now descended into one of the cavities made by long use of what to begin with was a cheap piece of furniture, feebly sprung. My knees rose high as my clavicles. My gun was concealed behind the books on the shelf four feet above and at least two to the left. Funny that when standing, with some chance of reaching it, I had thought rather of the mop in the hall toilet.

But it did occur to me now to cry for help. “Peggy! Call the police!” If indeed, bless her soul, she had not already done so: my fall against the couch must have shaken the entire floor of the old building.

At my appeal the giant broke open the lower, nasty half of his face and laughed, not with the volume and depth one would have expected, but rather as if he were whispering a series of fs.

“Schmuck,” he said then. “She went to lunch.”

Dumb bitch. I was more bitter at her desertion than by reason of his attack.

“You pack quite a wallop,” said I, choosing the vernacular as the proper idiom for obsequiousness. “I don’t intend to fight back. In a word, I’ll co-operate.”

He closed his eyes briefly and widened his mouth, as if uttering a silent prayer to the god of chagrin.