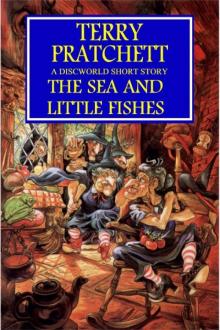

The Sea and Little Fishes

Terry Pratchett

About this Title

This eBook was created using ReaderWorks™ Publisher Preview, produced by OverDrive, Inc.

For more information on ReaderWorks, visit us on the Web at "www.readerworks.com"

THE SEA AND LITTLE FISHES

BY TERRY PRATCHETT

Trouble began, and not for the first time, with an apple.

There was a bag of them on Granny Weatherwax's bleached and spotless table. Red and round, shiny and fruity, if they'd known the future they should have ticked like bombs.

'Keep the lot, old Hopcroft said I could have as many as I wanted,' said Nanny Ogg. She gave her sister witch a sidelong glance.

'Tasty, a bit wrinkled, but a damn good keeper.'

'He named an apple after you?' said Granny. Each word was an acid drop on the air.

"Cos of my rosy cheeks,' said Nanny Ogg. 'An' I cured his leg for him after he fell off that ladder last year. An' I made him up some jollop for his bald head.'

'It didn't work, though,' said Granny. 'That wig he wears, that's a terrible thing to see on a man still alive.'

'But he was pleased I took an interest.'

Granny Weatherwax didn't take her eyes off the bag. Fruit and vegetables grew famously in the mountains' hot summers and cold winters. Percy Hopcroft was the premier grower and definitely a keen man when it came to sexual antics among the horticulture with a camel-hair brush.

'He sells his apple trees all over the place,' Nanny Ogg went on. 'Funny, eh, to think that pretty soon thousands of people will be having a bite of Nanny Ogg.'

'Thousands more,' said Granny, tartly. Nanny's wild youth was an open book, although only available in plain covers.

'Thank you, Esme.' Nanny Ogg looked wistful for a moment, and then opened her mouth in mock concern. 'Oh, you ain't jealous, are you, Esme? You ain't begrudging me my little moment in the sun?'

'Me? Jealous? Why should I be jealous? It's only an apple. It's not as if it's anything important.'

'That's what I thought. It's just a little frippery to humour an old lady,' said Nanny. 'So how are things with you, then?'

'Fine. Fine.'

'Got your winter wood in, have you?'

'Mostly.'

'Good,' said Nanny. 'Good.'

They sat in silence. On the windowpane a butterfly, awoken by the unseasonable warmth, beat a little tattoo in an effort to reach the September sun.

'Your potatoes ... got them dug, then?' said Nanny.

'Yes.'

'We got a good crop off ours this year.'

'Good.'

'Salted your beans, have you?'

'Yes.'

'I expect you're looking forward to the Trials next week?'

'Yes.'

'I expect you've been practising?'

'No.'

It seemed to Nanny that, despite the sunlight, the shadows were deepening in the corners of the room. The very air itself was growing dark. A witch's cottage gets sensitive to the moods of its occupant. But she plunged on. Fools rush in, but they are laggards compared to little old ladies with nothing left to fear.

'You coming over to dinner on Sunday?'

'What're you havin'?'

'Pork.'

'With apple sauce?'

'Ye -,

'No,' said Granny.

There was a creaking behind Nanny. The door had swung open.

Someone who wasn't a witch would have rationalised this, would have said that of course it was only the wind. And Nanny Ogg was quite prepared to go along with this, but would have added: why was it only the wind, and how come the wind had managed to lift the latch?

'Oh, well, can't sit here chatting all day,' she said, standing up quickly.

'Always busy at this time of year, ain't it?'

'Yes.'

'So I'll be off, then.'

'Goodbye.'

The wind blew the door shut again as Nanny hurried off down the path.

It occurred to her that, just possibly, she may have gone a bit too far.

But only a bit.

The trouble with being a witch - at least, the trouble with being a witch as far as some people were concerned - was that you got stuck out here in the country. But that was fine by Nanny. Everything she wanted was out here. Everything she'd ever wanted was here, although in her youth she'd run out of men a few times. Foreign parts were all right to visit but they weren't really serious. They had interestin' new drinks and the grub was fun, but foreign parts was where you went to do what might need to be done and then you came back here, a place that was real.

Nanny Ogg was happy in small places.

Of course, she reflected as she crossed the lawn, she didn't have this view out of her window. Nanny lived down in the town, but Granny could look out across the forest and over the plains and all the way to the great round horizon of the Discworld.

A view like that, Nanny reasoned, could probably suck your mind right out of your head.

They'd told her the world was round and flat, which was common sense, and went through space on the back of four elephants standing on the shell of a turtle, which didn't have to make sense. It was all happening Out There somewhere, and it could continue to do so with Nanny's blessing and disinterest so long as she could live in a personal world about ten miles across, which she carried around with her.

But Esme Weatherwax needed more than this little kingdom could contain. She was the other kind of witch.

And Nanny saw it as her job to stop Granny Weatherwax getting bored.

The business with the apples was petty enough, a spiteful little triumph when you got down to it, but Esme needed something to make every day worthwhile and if it had to be anger and jealousy then so be it. Granny would now scheme for some little victory, some tiny humiliation that only the two of them would ever know about, and that'd be that.

Nanny was confident that she could deal with her friend in a bad mood, but not when she was bored. A witch who is bored might do anything.

People said things like 'we had to make our own amusements in those days' as if this signalled some kind of moral worth, and perhaps it did, but the last thing you wanted a witch to do was get bored and start making her own amusements, because witches sometimes had famously erratic ideas about what was amusing. And Esme was undoubtedly the most powerful witch the mountains had seen for generations.

Still, the Trials were coming up, and they always set Esme Weatherwax all right for a few weeks. She rose to competition like a trout to a fly.

Nanny Ogg always looked forward to the Witch Trials. You got a good day out and of course there was a big bonfire. Whoever heard of a Witch Trial without a good bonfire afterwards?

And afterwards you could roast potatoes in the ashes.

The afternoon melted into the evening, and the shadows in corners and under stools and tables crept out and ran together.

Granny rocked gently in her chair as the darkness wrapped itself around her. She had a look of deep concentration.

The logs in the fireplace collapsed into the embers, which winked out one by one.

The night thickened.

The old clock ticked on the mantelpiece and, for some length of time, there was no other sound.

There came a faint rustling. The paper bag on the table moved and then began to crinkle like a deflating balloon. Slowly, the still air filled with a heavy smell of decay.

After a while the first maggot crawled out.

Nanny Ogg was back home and just pouring a pint of beer when there was a knock. She put down the jug with a sigh, and went and opened the door.

'Oh, hello, ladies. What're you doing in these parts? And on such a chilly evening, too?'

Nanny backed into the room,

ahead of three more witches. They wore the black cloaks and pointy hats traditionally associated with their craft, although this served to make each one look different. There is nothing like a uniform for allowing one to express one's individuality.

A tweak here and a tuck there are little details that scream all the louder in the apparent, well, uniformity.

Gammer Beavis's hat, for example, had a very flat brim and a point you could clean your ear with. Nanny liked Gammer Beavis. She might be a bit too educated, so that sometimes it overflowed out of her mouth, but she did her own shoe repairs and took snuff and, in Nanny Ogg's small world view, things like this meant that someone was All Right.

Old Mother Dismass's clothes had that disarray of someone who, because of a detached retina in her second sight, was living in a variety of times all at once. Mental confusion is bad enough in normal people, but much worse when the mind has an occult twist. You just had to hope it was only her underwear she was wearing on the outside.

It was getting worse, Nanny knew. Sometimes her knock would be heard on the door a few hours before she arrived. Her footprints would turn up several days later.

Nanny's heart sank at the sight of the third witch, and it wasn't because Letice Earwig was a bad woman. Quite the reverse, in fact.

She was considered to be decent, well-meaning and kind, at least to less-aggressive animals and the cleaner sort of children. And she would always do you a good turn. The trouble was, though, that she would do you a good turn for your own good even if a good turn wasn't what was good for you. You ended up mentally turned the other way, and that wasn't good.

And she was married. Nanny had nothing against witches being married. It wasn't as if there were rules. She herself had had many husbands, and had even been married to three of them. But Mr Earwig was a retired wizard with a suspiciously large amount of gold, and Nanny suspected that Letice did witchcraft as something to keep herself occupied, in much the same way that other women of a certain class might embroider kneelers for the church or visit the poor.

And she had money. Nanny did not have money and therefore was predisposed to dislike those who did. Letice had a black velvet cloak so fine that if looked as if a hole had been cut out of the world.

Nanny did not. Nanny did not want a fine velvet cloak and did not aspire to such things. So she didn't see why other people should have them.

"Evening, Gytha. How are you keeping, in yourself?' said Gammer Beavis.

Nanny took her pipe out of her mouth. 'Fit as a fiddle. Come on in.'

'Ain't this rain dreadful?' said Mother Dismass. Nanny looked at the sky. It was frosty purple. But it was probably raining wherever Mother's mind was at.

'Come along in and dry off, then,' she said kindly.

'May fortunate stars shine on this our meeting,' said Letice.

Nanny nodded understandingly. Letice always sounded as though she'd learned her witchcraft out of a not very imaginative book.

'Yeah, right,' she said.

There was some polite conversation while Nanny prepared tea and scones. Then Gammer Beavis, in a tone that clearly indicated that the official part of the visit was beginning, said,

'We're here as the Trials committee, Nanny.'

'Oh? Yes?'

'I expect you'll be entering?'

'Oh, yes. I'll do my little turn.' Nanny glanced at Letice.

There was a smile on that face that she wasn't entirely happy with.

'There's a lot of interest this year,' Gammer went on. 'More girls are taking it up lately.'

'To get boys, one feels,' said Letice, and sniffed. Nanny didn't comment. Using witchcraft to get boys seemed a damn good use for it as far as she was concerned. It was, in a way, one of the fundamental uses.

'That's nice,' she said. 'Always looks good, a big turnout. But.'

'I beg your pardon?' said Letice.

'I said "but",' said Nanny, ' 'cos someone's going to say "but", right? This little chat has got a big "but" coming up. I can tell.'

She knew this was flying in the face of protocol. There should be at least seven more minutes of small talk before anyone got around to the point, but Letice's presence was getting on her nerves.

'It's about Esme Weatherwax,' said Gammer Beavis.

'Yes?' said Nanny, without surprise.

'I suppose she's entering?'

'Never known her stay away.'

Letice sighed.

'I suppose you ... couldn't persuade her to . .. not to enter this year?'

Nanny looked shocked.

'With an axe, you mean?'

In unison, the three witches sat back.

'You see -' Gammer began, a bit shamefaced.

'Frankly, Mrs Ogg,' said Letice, 'it is very hard to get other people to enter when they know that Miss Weatherwax is entering. She always wins.'

'Yes,' said Nanny. 'It's a competition.'

'But she always wins!'

'So?'

'In other types of competition,' said Letice, 'one is normally only allowed to win for three years in a row and then one takes a back seat for a while.'

'Yeah, but this is witching,' said Nanny. 'The rules is different.'

'How so?'

'There ain't none.'

Letice twitched her skirt. 'Perhaps it is time there were,' she said.

'Ah,' said Nanny. 'And you just going to go up and tell Esme that? You up for this, Gammer?'

Gammer Beavis didn't meet her gaze. Old Mother Dismass was gazing at last week.

'I understand Miss Weatherwax is a very proud woman,' said Letice.

Nanny Ogg puffed at her pipe again.

'You might as well say the sea is full of water,' she said.

The other witches were silent for a moment.

'I daresay that was a valuable comment,' said Letice, 'but I didn't understand it.'

'If there ain't no water in the sea, it ain't the sea,' said Nanny Ogg. 'It's just a damn great hole in the ground. Thing about Esme is ...'

Nanny took another noisy pull at the pipe, 'she's all pride, see? She ain't just a proud person.'

'Then perhaps she should learn to be a bit more humble...'

'What's she got to be humble about?' said Nanny sharply.

But Letice, like a lot of people with marshmallow on the outside, had a hard core that was not easily compressed.

'The woman clearly has a natural talent and, really, she should be grateful for...'

Nanny Ogg stopped listening at this point. The woman, she thought. So that was how it was going.

It was the same in just about every trade. Sooner or later someone decided it needed organizing, and the one thing you could be sure of was that the organizers weren't going to be the people who, by general acknowledgement, were at the top of their craft. They were working too hard. To be fair, it generally wasn't done by the worst, neither. They were working hard, too. They had to.

No, it was done by the ones who had just enough time and inclination to scurry and bustle. And, to be fair again, the world needed people who scurried and bustled. You just didn't have to like them very much.

The lull told her that Letice had finished.

'Really? Now, me,' said Nanny, 'I'm the one who's nat'rally talented. Us Oggs've got witchcraft in our blood. I never really had to sweat at it. Esme, now ... she's got a bit, true enough, but it ain't a lot. She just makes it work harder'n hell. And you're going to tell her she's not to?'

'We were rather hoping you would,' said Letice.

Nanny opened her mouth to deliver one or two swearwords, and then stopped.

'Tell you what,' she said, 'you can tell her tomorrow, and I'll come with you to hold her back.'

Granny Weatherwax was gathering Herbs when they came up the track.

Everyday herbs of sickroom and kitchen are known as simples.

Granny's Herbs weren't simples. They were complicateds or they were nothing. And there was none of the airy-fairy business with a pretty basket and a pair of dainty sni

ppers. Granny used a knife. And a chair held in front of her. And a leather hat, gloves and apron as secondary lines of defence.

Even she didn't know where some of the Herbs came from. Roots and seeds were traded all over the world, and maybe further. Some had flowers that turned as you passed by, some fired their thorns at passing birds and several were staked, not so that they wouldn't fall over, but so they'd still be there next day.

Nanny Ogg, who never bothered to grow any herb you couldn't smoke or stuff a chicken with, heard her mutter, 'Right, you buggers - '

'Good morning, Miss Weatherwax,' said Letice Earwig loudly.

Granny Weatherwax stiffened, and then lowered the chair very carefully and turned around.

'It's Mistress,' she said.

'Whatever,' said Letice brightly. 'I trust you are keeping well?'

'Up till now,' said Granny. She nodded almost imperceptibly at the other three witches.

There was a thrumming silence, which appalled Nanny Ogg. They should have been invited in for a cup of something. That was how the ritual went. It was gross bad manners to keep people standing around.

Nearly, but not quite, as bad as calling an elderly unmarried witch 'Miss'.

'You've come about the Trials,' said Granny. Letice almost fainted.

'Er, how did -'

"Cos you look like a committee. It don't take much reasoning,' said Granny, pulling off her gloves. 'We didn't used to need a committee. The news just got around and we all turned up. Now suddenly there's folk arrangin' things.' For a moment Granny looked as though she was fighting some serious internal battle, and then she added in throwaway tones: 'Kettle's on. You'd better come in.'

Nanny relaxed. Maybe there were some customs even Granny Weatherwax wouldn't defy, after all. Even if someone was your worst enemy, you invited them in and gave them tea and biscuits. In fact, the worser your enemy, the better the crockery you got out and the higher the quality of the biscuits. You might wish black hell on 'em later, but while they were under your roof you'd feed 'em till they choked.

Her dark little eyes noted that the kitchen table gleamed and was still damp from scrubbing.

After cups had been poured and pleasantries exchanged, or at least offered by Letice and received in silence by Granny, the self-elected chairwoman wriggled in her seat and said: