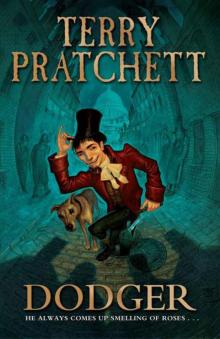

Dodger

Terry Pratchett

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Author’s Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Terry Pratchett

Copyright

About the Book

Dodger is a tosher – a sewer scavenger

living in the squalor of Dickensian London.

Everyone who is nobody knows him.

Anyone who is anybody doesn’t.

He used to know his future; it involved a lot of

brick-lined tunnels and plenty of filth.

But when he rescues a young girl from a beating,

things start to get really messy.

Now everyone who is anyone

wants to get their hands on Dodger.

To Henry Mayhew for writing his book,

and to Lyn for absolutely

everything else

CHAPTER 1

In which we meet our hero, and the hero meets an orphan of the storm and comes face to face with Mister Charlie, a gentleman known as a bit of a scribbler

THE RAIN POURED down on London so hard that it seemed that it was dancing spray, every raindrop contending with its fellow for supremacy in the air and waiting to splash down. It was a deluge. The drains and sewers were overflowing, throwing up – regurgitating, as it were – the debris of muck, slime and filth, the dead dogs, the dead rats, cats and worse; bringing back up to the world of men all those things that they thought they had left behind them; jostling and gurgling and hurrying towards the overflowing and always hospitable river Thames; bursting its banks, bubbling and churning like some nameless soup boiling in a dreadful cauldron; the river itself gasping like a dying fish. But those in the know always said about the London rain that, try as it might, it would never, ever clean that noisome city, because all it did was show you another layer of dirt. And on this dirty night there were appropriately dirty deeds that not even the rain could wash away.

A fancy two-horse coach wallowed its way along the street, some piece of metal stuck near an axle causing it to be heralded by a scream. And indeed there was a scream, a human scream this time, as the coach door was flung open and a figure tumbled out into the gushing gutter, which tonight was doing the job of a fountain. Two other figures sprang from the coach, cursing in language that was as colourful as the night was dark and even dirtier. In the downpour, fitfully lit by the lightning, the first figure tried to escape but tripped, fell and was leaped upon, with a cry that was hardly to be heard in all the racket, but which was almost supernaturally counterpointed by the grinding of iron, as a drain cover nearby was pushed open to reveal a struggling and skinny young man who moved with the speed of a snake.

‘You let that girl alone!’ he shouted.

There was a curse in the dark and one of the assailants fell backwards with his legs kicked from under him. The youth was no heavyweight but somehow he was everywhere, throwing blows – blows which were augmented by a pair of brass knuckles, always a helpmeet for the outnumbered. Outnumbered one to two as it were, the assailants took to their heels while the youth followed, raining blows. But it was London and it was raining and it was dark, and they were dodging into alleys and side streets, frantically trying to catch up with their coach, so that he lost them, and the apparition from the depths of the sewers turned round and headed back to the stricken girl at greyhound speed.

He knelt down, and to his surprise she grabbed him by the collar and whispered in what he considered to be foreigner English, ‘They want to take me back, please help me . . .’ The lad sprang to his feet, his eyes all suspicion.

On this stormy night of stormy nights, it was opportune then that two men who themselves knew something about the dirt of London were walking, or rather, wading, along this street, hurrying home with hats pulled down – which was a nice try, but simply didn’t work, because in this torrent it seemed that the bouncing water was coming as much from below as it was from above. Lightning struck again, and one of them said, ‘Is that someone lying in the gutter there?’ The lightning presumably heard, because it sliced down again and revealed a shape, a mound – a person, as far as these men could see.

‘Good heavens, Charlie, it’s a girl! Soaked to the skin and thrown into the gutter, I imagine,’ said one of them. ‘Come on . . .’

‘Hey, you, what are you a-doing, mister?!’

By the light of a pub window which could barely show you the darkness, the aforesaid Charlie and his friend saw the face of a boy who looked like a young lad no more than seventeen years old but who seemed to have the voice of a man. A man, moreover, who was prepared to take on both of them, to the death. Anger steamed off him in the rain and he wielded a long piece of metal. He carried on, ‘I know your sort, oh yes I do! Coming down here chasing the skirt, making a mockery of decent girls. Blimey! Desperate, weren’t you, to be out on a night such as this!’

The man who wasn’t called Charlie straightened up. ‘Now see here, you. I object most strongly to your wretched allegation. We are respectable gentlemen who, I might add, work quite hard to better the fortunes of such poor wretched girls and, indeed, by the look of it, those such as yourself!’

The scream of rage from the boy was sufficiently loud that the doors of the nearby pub swung open, causing smoky orange light to illuminate the ever-present rain. ‘So that’s what you call it, is it, you smarmy old gits!’

The boy swung his home-made weapon but the man called Charlie caught it and dropped it behind him, then grabbed the boy and held him by the scruff of his neck. ‘Mister Mayhew and myself are decent citizens, young man, and as such we surely feel it is our duty to take this young lady somewhere away from harm.’ Over his shoulder he said, ‘Your place is closest, Henry. Do you think your wife would object to receiving a needy soul for one night? I wouldn’t like to see a dog out on a night such as this.’

Henry, now clutching the young woman, nodded. ‘Do you mean two dogs, by any chance?’

The struggling boy took immediate offence at this, and with a snake-like movement was out of the grip of Charlie, and once again spoiling for a fight. ‘I ain’t no dog, you nobby sticks, nor ain’t she! We have our pride, you know. I make my own way, I does, all kosher, straight up!’

The man called Charlie lifted the boy up by the scruff of his neck so that they were face to face. ‘My, I admire your attitude, young man, but not your common sense!’ he said quietly. ‘And mark you, this young lady is in a bad way. Surely you can see that. My friend’s house is not too far away from here, and since you have set yourself up as her champion and protector, why then, I invite you to follow us there and witness that she will have the very best of treatment that we can afford, do you hear me? What is your name, mister? And before you tell it to me, I invite you to believe that you are not the only person who cares about a young lady in dire trouble on this dreadful night. So, my boy, what is your name?’

The boy must have picked up a tone in Charlie’s voice, because he said, ‘I’m Dodger – that’s what they call me, on account I’m never there, if you see what I mean? Everybody in all the boroughs knows Dodger.’

‘Well, then,’ said Charlie. ‘Now we have met you and joined that august company, we must see if we can come to an understanding during this little odyssey, man to man.’ He straightened up and went on,

‘Let us move, Henry, to your house and as soon as possible, because I fear this unfortunate girl needs all the help we can give her. And you, my lad, do you know this young lady?’

He let go of the boy, who took a few steps backwards. ‘No, guv’nor, never seen her before in my life, God’s truth, and I know everybody on the street. Just another runaway – happens all the time, so it does; it don’t bear thinking about.’

‘Am I to believe, Mister Dodger, that you, not knowing this unfortunate woman, nevertheless sprang to her defence like a true Galahad?’

Dodger suddenly looked very wary. ‘I might be, I might not. What’s it to you, anyway? And who the hell is this Galahad cove?’

Charlie and Henry made a cradle with their arms to carry the woman. As they set off, Charlie said over his shoulder, ‘You have no idea what I just said, do you, Mister Dodger? But Galahad was a famous hero . . . Never mind – you just follow us, like the knight in soaking armour that you are, and you will see fair play for this damsel, get a good meal and, let me see . . .’ Coins jingled in the darkness. ‘Yes, two shillings, and if you do come you will perhaps improve your chances of Heaven, which, if I am any judge, is not a place that often concerns you. Understand? Do we have an accord? Very well.’

Twenty minutes later, Dodger was sitting close to the fire in the kitchen of a house – not a grand house as such, but nevertheless much grander than most buildings he went into legally; there were much grander buildings that he had been into illegally, but he never spent very much time in them, often leaving with a considerable amount of haste. Honestly, the number of dogs people had these days was a damn scandal, so it was, and they would set them on a body without warning, so he had always been speedy. But here, oh yes, here there was meat and potatoes, carrots too, but not, alas, any beer. In the kitchen he had been given a glass of warm milk which was nearly fresh. Mrs Quickly the cook was watching him like a hawk and had already locked away the cutlery, but apart from that it seemed to be a pretty decent crib, although there had been a certain amount of what you might call words from the missus of Mister Henry to her husband on the subject of bringing home waifs and strays at this time of night. It seemed to Dodger, who paid a great deal of forensic attention to all he could see and hear, that this was by no means the first time that she had cause for complaint; she sounded like someone trying hard to conceal that they were really fed up, and trying to put a brave face on it. But nevertheless, Dodger had certainly had his meal (and that was the important thing), the wife and a maid had bustled off with the girl, and now . . . someone was coming down the stairs to the kitchen.

It was Charlie, and Charlie bothered Dodger. Henry seemed like one of them do-gooders who felt guilty about having money and food when other people did not; Dodger knew the type. He, personally, was not bothered about having money when other people didn’t, but when you lived a life like his, Dodger found that being generous when in funds, and being a cheerful giver, was a definite insurance. You needed friends – friends were the kind of people who would say: ‘Dodger? Never heard of ’im, never clapped eyes on ’im, guv’nor! You must be thinking of some other cove’ – because you had to live as best you could in the city, and you had to be sharp and wary and on your toes every moment of the day if you wanted to stay alive.

He stayed alive because he was the Dodger, smart and fast. He knew everybody and everybody knew him. He had never, ever, been before the beak, he could outrun the fastest Bow Street runner and, now that they had all been found out and replaced, he could outrun every peeler as well. They couldn’t arrest you unless they put a hand on you, and nobody ever managed to touch Dodger.

No, Henry was no problem, but Charlie – now, oh yes, Charlie – he looked the type who would look at a body and see right inside you. Charlie, Dodger considered, might well be a dangerous cove, a gentleman who knew the ins and outs of the world and could see through flannel and soft words to what you were thinking, which was dangerous indeed. Here he was now, the man himself, coming downstairs escorted by the jingling of coins.

Charlie nodded at the cook, who was cleaning up, and sat down on the bench by Dodger, who had to slide up a bit to make room.

‘Well now, Dodger, wasn’t it?’ he said. ‘I am sure you will be very happy to know that the young lady you helped us with is safe and sleeping in a warm bed after some stitches and some physic from the doctor. Alas, I wish I could say the same for her unborn child, which did not survive this dreadful escapade.’

Child! The word hit Dodger like a blackjack, and unlike a blackjack it kept on going. A child – and for the rest of the conversation the word was there, hanging at the edge of his sight and not letting him go. Aloud he said, ‘I didn’t know.’

‘Indeed, I’m sure you didn’t,’ said Charlie. ‘In the dark it was just one more dreadful crime, which without doubt was only one among many this night; you know that, Dodger, and so do I. But this one had the temerity to take place in front of me, and so I feel I would like to do a little police work, without, as it were, involving the police, who I suspect in this case would not have very much success.’

Charlie’s face was unreadable, even to Dodger, who was very, very good at reading faces. Solemnly, the man went on, ‘I wonder if those gentlemen you met who were harassing her knew about the child; perhaps we shall never find out, or perhaps we shall.’ And there it was; that little word ‘shall’ was a knife, straining to cut away until it hit enlightenment. Charlie’s face stayed totally blank. ‘I wonder if any other gentleman was aware of the fact, and therefore, sir, here for you are your two shillings – plus one more, if you were to answer a few questions for me in the hope of getting to the bottom of this strange occurrence.’

Dodger looked at the coins. ‘What sort of questions would they be, then?’ Dodger lived in a world where nobody asked questions apart from: ‘How much?’ and ‘What’s in it for me?’ And he knew, actually knew, that Charlie knew this too.

Charlie continued. ‘Can you read and write, Mister Dodger?’

Dodger put his head on one side. ‘Is this a question that gets me a shilling?’

‘No, it does not,’ Charlie snapped. ‘But I will spring one farthing for that little morsel and nothing more; here is the farthing, where is the answer?’

Dodger grabbed the tiny coin. ‘Can read “beer”, “gin” and “ale”. No sense in filling your head with stuff you don’t need, that’s what I always say.’ Was that the tiny ghost of a smile on the man’s face? he wondered.

‘You are clearly an academic, Mister Dodger. Perhaps I should tell you that the young lady had, well, she had not been well used.’

He wasn’t smiling any more, and Dodger, suddenly panicking, shouted, ‘Not by me! I never done nothing to hurt her, God’s truth! I might not be an angel but I ain’t a bad man!’

Charlie’s hand grabbed Dodger as he tried to get up. ‘You never done nothing? You, Mister Dodger, never done nothing? If you never done nothing then you must have done something, and there you are, guilty right out of your own mouth. I’m quite certain that you yourself have never been to school, Mister Dodger; you seem far too smart. Though if you ever did, and came out with a phrase like “I never done nothing”, you would probably be thrashed by your teacher. But now listen to me, Dodger; I fully accept that you did nothing to harm the lady, and I have one very good reason for saying so. You might not be aware of it, but on her finger there is one of the biggest and most ornate gold rings I have ever seen – the sort of ring that means something – and if you were intending to do her any harm you would have stolen it in a wink, just like you stole my pocketbook a short while ago.’

Dodger looked at those eyes. Oh, this was a bad cove to be on the wrong side of and no two ways about it. ‘Me, sir? No, sir,’ he said. ‘Found it lying around, sir. Honestly intended to give it back to you, sir.’

‘I can assure you that I believe in full every word you have just uttered, Mister Dodger. Although I must confess my admiration that in the darkness you

were not only able to see the form of a pocketbook, but also so readily decided that it belonged to me; really I’m quite amazed,’ said Charlie. ‘Settle down; I just wanted you to know how serious we are. When you said, “I never done nothing”, all you were doing was painting the whole of your statement with negativity, crudely but with emphasis, you understand? Myself and Mister Mayhew are cognisant of the generally unacceptable state of affairs throughout most of this city, and by the way, that means we know about such things and endeavour in our various ways to bring matters to the notice of the public, or at least to those members of the public who care to take notice. Since you appear to care about the young lady, perhaps you could ask around or at least listen for any news about her; where she came from, her background, anything about her. She was badly beaten, and I don’t mean a domestic up-and-downer, a slap, maybe. I mean leather and fists. Fists! Over and over again, according to the bruises, and that, my young friend, wasn’t the end of it!

‘Now there are some people, not you of course, who would say we should go to the authorities, and this is because they have no grasp at all of the realities of London for the lower classes; no grasp at all of the rookeries and the detritus of decay and squalor that is their lot. Yes?’

This was because Dodger had raised a finger, and as soon as he saw that he had got Charlie’s full attention the boy said, ‘OK, certainly it can be a bit grubby down some streets. A few dead dogs, dead old lady maybe, but well, that’s the way of the world, right? Like it says in the Good Book, you got to eat a peck of dirt before you die, right?’

‘Possibly not all in one meal,’ said Charlie. ‘But since you raise the subject, Mister Dodger, for your two shillings, and one more shilling, quote me one further line from the Bible, if you please?’

This seemed something of an exercise for Dodger. He glared at the man and managed, ‘Well, mister, you have to goeth – yes, that’s what it says, and I don’t see no shilling yet!’