Swindler & Son

Ted Krever

Contents

Copyright and credits

Preface

Start

Running

The Office

Harry Time

Lost at Home

Regrets

Sara

Kidnapped

The Party

New Business

Cross Purposes

Allies

Diversion

Dreams

Meeting

The Protected

Qumradhi, Wadiirah

Grand Prix

Real Estate

The Reveal

Negotiation

Stealing A Ship

Spin

The Last Act

Acknowledgments

Reviews

Author Biography

© 2018 Ted Krever

all rights reserved

~~~~

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual places, events or Persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

~~~~

ISBN: 976-1-7327865-4-7

~~~~

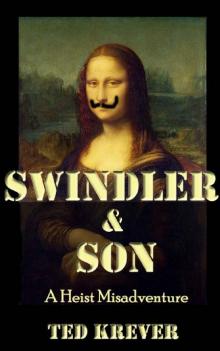

Cover painting by Da Vinci, public domain

Graffiti by author

~~~~

Author Photo by CO Moed

used with permission

~~~~

Preface

‘Did you torture him?’

Captain Segura laughed. ‘No. He doesn’t belong to the torturable class.’

- Our Man In Havana, Graham Greene

The Start

-So how does it start?

It starts with the sound of my own name spoken aloud.

Call me Nicholas, I’m fine. Nick or Nicky, even better.

But ‘Nicholas Marsh’ enunciated, first and last, all the way through—when I hear it that way, I know I’ve done something I’m about to pay for.

Hearing it in French, every syllable twisted and slurred and leaking from the earpiece of a Parisian counter-terrorism officer in a Kevlar vest, his back to me and his binoculars trained on my kitchen window—that’s rock-bottom.

That’s how it starts, in the snowy garden of the Hopital Saint-Louis in the Tenth Arrondissement, just past sundown on Christmas day, at what I fervently hoped was the end of one of the worst days of my life.

Well, actually, no…

Actually, it started about fifteen minutes earlier, on the other side of the canal, where I was mugged by some twenty-five year old junkie in a purple-tinted mohawk and a leather jacket. And several nice tats on his neck that distracted my attention when I should have been focusing on his oncoming fist. He took my wallet and phone and left me aching and dizzy, which is why I wandered groggy several blocks out of my way and approached home through the garden.

I love that garden but none of the official exits land anywhere near my apartment. A few years ago, I found a back door, through the Musee des Moulages on the hospital grounds, that let me out near a construction gate right across the street from my building.

I’m just opening that back door when I hear my name and see GIGN, French Special Forces, two officers, huddled like Martians in flak suits, gas masks and sniper rifles, peeking through the construction gate at the wide corner, the entrance to my building and, eight floors above, at the dead coleus drooping from my night table.

Frozen in place, I scan the rooftops to find a squad of dark gray uniforms—and, in case I harbor any last doubts, hear my name one more time from the headset hanging from the blonde officer’s right ear. I back instinctively into the doorway, sweating and making twenty-five different plans at the same time.

The bus! They won’t be checking the bus on the Boulevard de la Villette, that’s an answer. Having any sort of answer calms the quiver in my legs, brings them back into something like working order.

This is a mistake—it’s got to be. If I’d done something to deserve counter-terrorism, I’d remember it, wouldn’t I? More importantly, why in hell didn’t somebody tip me off? Who do I know at GIGN?

Out through the door and the museum, retracing my steps, back out the far end of the compound, past the Chapelle to the Rue de la Grange aux Belles. Up toward the roundabout at a regular clip, walking briskly like a Parisian.

Am I thinking of escape? Hell no, I’m just getting pissed. Why hasn’t somebody warned me? Why haven’t they given me a chance to buy my way out of this?

Oh sure, GIGN makes it look serious but that just raises the price. I know somebody in every department of government and what they cost. Serious things have been undone before.

By the time the bus makes three stops, I know who to talk to—Beltoise, the second man at the Surete. He was at our Christmas party just last night.

I own him! At least, I should. If I had a middle-class clientele, if I dealt pot or owned a brothel, I could expect a phone call 24 hours in advance of a raid. It’s common courtesy!

He’ll be at D’Azur, of course, charging his dinner to us as usual.

When I arrive, he’s tucked into a dim corner. He rises before I can reach him.

“Why is GIGN all around my apartment? You don’t warn me?”

His eyes bulge like marbles. “Where’s your phone?”

“Phone? Stolen. I got mugged.”

He looks relieved. “That’s why they’re not here yet,” he mutters and pulls me into the private room in back.

“Nicky, our past history—and the fact that I like you—is why I’ll give you a minute’s grace before I call you in.” He’s serious! His face goes cold—not like he doesn’t know me, like he’s never seen me before. “Normal corruption is one thing—but this?”

Normal corruption? Normal corruption is my specialty! He’s reducing ten thousand years of civilized give-and-take to a catchphrase. Not to mention, it’s fed him quite nicely, thank you, over the years.

I look at his face, at the disappointment and condescension there, and realize what a farce it all is. You treat them like princes but the first time you actually need them to put out…they might as well be in insurance.

Faced with this ingratitude, something inside me just gives up.

“Okay,” I tell him. “I surrender.”

“What?”

“I’ll confess, right now. It’s the jet ramps, isn’t it?”

He looks confused.

“We have this client, a dictator…you know the old joke about, you’re not really a country unless you have your own stamps, your own airline and your own beer? Well, he’s got commemorative stamps, a brewery, a Mercedes stretch limo and a portrait of himself as Julius Caesar. But he gets embarrassed when his guests have to descend a staircase off the plane.

“There’s a staircase on Air Force One’ I tell him and he says, ‘They could have a ramp if they wanted one.’ So when Kumbatta collapsed, we flew a cargo plane in and liberated a couple of jetramps. The guy was so happy, he painted two Cessna’s and proclaimed them the national airline. I don’t think we hurt anybody.”

Beltoise settles into the nearest chair, not saying a word.

“That’s not it?”

Silence.

“Okay, Napoleon’s penis—that was a good deed, I swear.”

“Excusez moi?”

“It’s your Minister of Defence’s fault! Not the present Minister, the old one. He had this…thing about Napoleon’s penis, that it should be back in France where it belongs.”

“It is in France! Napoleon’s body is at Les Invalides!”

“The body, sure, but his penis was removed during the autopsy and it’s floated around ever since from collector to collector. It’s now owned by a urologist, naturally, in Philadelphia.”

“Don’t be funny

.”

“It’s true. The BBC measured it a few years ago and found it a bit small. Naturally, that outraged the Minister, who insisted the English don’t know how to measure. The urologist’s price was just outrageous so we found a…more generously-sized one around the same age, for a price the Minister could afford. It made him happy.”

“You found him another penis?”

“Another old penis! You think that was easy? How many three-hundred-year-old penises you think are floating around?”

Beltoise stares at me with—I can’t tell if it’s respect or concern. The odd thing is, to me, this is actually beginning to feel pretty righteous. Confession really is good for the soul. “Okay, not the answer. Give me a chance. The eighteen identical one-of-a-kind Moroccan emeralds—”

“No.”

“The Van Gogh with the wrong ear missing?”

Beltoise rolls his eyes. “We’ve never met,” he warns, “except for a few state dinners with hundreds of other people I’ve never met either—but my advice is, you find a quick way out of France now. And don’t bother replacing your phone—they’ll find you as soon as you do. You understand?”

This is terrifying—Beltoise is a glorified flatfoot with a fancy office. I’m begging to be arrested and he’s not biting. It’s unnatural.

“Throw me a bone here,” I say. “I don’t understand what’s happened.”

He grimaces. “You know damn well it’s the bomb.”

“The BOMB?”

Of course, I know all about the bomb. I’d arrived back in Paris the day before, just in time for the funerals. Twelve dead, 37 injured, a miracle it wasn’t more. A mountain of flowers in plastic sleeves heaped on the rubble, candles arrayed like soldiers in front of the dress shop left somehow intact on the corner.

And a march from the Place De la Republique to the Place de la Nacion, thousands, orderly and dogged, middle-class families and university students, Le President and his rivals, butchers, bakers, artists and computer technicians shuffling through neighborhood streets between broad public squares, solemn and chattering, sombre but fashionable—Paris, formal but somehow intimate. Great buildings and beautiful women dressed in black. Paris is a grand dame, maybe a bit past her prime, but she still knows how to put on a funeral.

‘It’s an escalation,’ they say, the voices that multiply in crowds. Just a few years ago, ‘they’ were content to shoot up a restaurant or concert hall. Now, somehow, they bring in a bomb the size of a safe to bring down half a block of five-story apartment buildings.

The size of the explosion makes people nervous. Nobody builds a bomb that size to bring down the Rue Breguet. We all sense a grander plan that went awry and the fact that no one claimed responsibility only seems to heighten the tension. You don’t even have the consolation of knowing who to be afraid of.

Beltoise, however, has made up his mind.

“It’s your shipping certificate!” he yells, no longer caring who hears. “Your company’s letterhead! Your signature on the bloody thing! You think I will cover for that, you’re insane!”

I stand frozen for an endless moment, until words I never thought I’d hear myself say come tumbling out of my mouth.

“I didn’t do that! I’m innocent!”

And then, I run.

Running

-You ran?

It’s an expression. I know better than to run. I walk at my usual quick pace but not fast enough to attract attention. Okay?

I lose myself in the tangle of back streets, staying off the boulevards, sticking to shorter blocks and parks where I can change direction at will. I stop short in front of angled store windows several times, switch direction several more, take a cab for a short distance and then another to double-back on myself. I’m overdoing it, in truth—if GIGN were really on my tail, they’d just throw on the sirens and take me. Once I’m sure I’m not being followed, I find a thrift shop that’s just closing in a church, buy a pair of slacks and a short dark hoodie and wear them out of the store.

-This is tradecraft. Where did you acquire your technique?

Like you don’t know. I had a very brief career in—what do you tell strangers at parties? About what you do for a living?

-I don’t speak of such things.

We used to call it ‘compliance.’ I was recruited out of college. They trained me to take in a room or a street, to be invisible when that was useful. Trust no one, calculate the odds, tote up the angles and assume everyone follows their own self-interest.

But they couldn’t teach me to be shrewd. I got myself involved in an ‘extracurricular’ scheme supporting freedom fighters—that is, it became extracurricular once it led to screaming headlines. Next thing I know, I’m getting chewed out in front of a Congressional committee for the exact same things they’d urged us to do in private.

We were thrown out like Big Mac wrappers, three fall guys, small potatoes. A generous severance package—under the table, of course—just go quietly into the night, thank you.

That training comes back to me, now that I’m on the run. Focus! The bomb! What have I got to do with the fucking bomb?

I need real information. Somewhere in our files, says Beltoise, is a shipping certificate for a bomb with my signature on it. I can’t go home so I almost certainly can’t go back to the office. But maybe Harry’s apartment is clear.

If this had happened any other time—last week, even!—I could have counted on Harry’s counsel, his expertise, his instincts. For fifteen years, he’s been there when I needed him.

But that’s a huge part of what made this feel like the worst day of my life, even before GIGN’s visit. I’ve no idea if I can count on Harry anymore.

-Explain this please. Who is this Harry and why can’t you count on him?

Harry is the majordomo, the ringmaster of our circus, the senior partner in Sandler & Son, affectionately known to staff and select members of the governing elite as Swindler & Son. Everything that isn’t about Sara in this story is about Harry.

-And Harry’s got problems?

Oh hell no, Harry’s got no problems. Harry is the problem. Everybody loves Harry, that’s the problem.

And why shouldn’t they? Harry makes life a party, a twenty-four-hour Remy Martin and shellfish from the little inlet over there and put away your business cards, this isn’t some vulgar networking grind, we’re here to have fun! Remember fun? Harry does.

If you liked the Remy, you must try this cognac—it’s Venetian, Dante mentioned it (disparagingly, but he mentioned it) in the Divine Comedy and let me introduce you to the Ambassador’s wife, she has all the good gossip about the orgies at that other embassy—maybe it was the Czechs but we’re not saying. Meanwhile, other groups are discussing 70’s film and sex robots and if there’s anything else you want to know, the person to speak to is over there. The band plays good acoustic jazz, the Argentine tango couple are giving lessons one-on-one on the terrace and the star of the national football club is kicking balls around with enchanted kids and dazzled grownups on the south lawn.

In Paris, of course. That’s our home base. It’s one of God’s jokes—Harry hated the French so, once we’d been thrown out of every other country in Europe, the only place left to go was Paris. Which, of course, he now loves because how can you not love Paris? It’s Paris, for God’s sake.

And the French love Harry. Big gnarly elegant gay Englishman, what’s not to love? He ignores their culture, conducts himself like tenth-generation nobility fallen to trade or maybe a good Savile Row tailor, speaks only enough French to be fed and catered to but laughs and charms so naturally, they can’t help themselves. Seduction is the French national pastime; they recognize a Master at work.

I was in Mumbai two years ago, picking up a load of Indian cotton. There was a rash of suicides among cotton farmers in Vidarbha and I was able to pick up several farms’ entire crop just by paying off the bank loans. I told myself it was a good deed and a good deal. So I’m in the hotel bar at the end of

the day chatting up some girl when a man behind me says, “Oh, you work with Harry Sandler? I was in a steeplechase syndicate with him in Ireland once. Took me for £65,000 quid. Most wonderful time I ever had.” He bought us both a drink.

Everybody loves Harry; that’s what nearly killed us all. As I watched the Iranian commandos lining up on the deck of the ship three hours ago, in their black stocking caps and their Kalashnikovs aimed at our temples, all I could think was, Everybody loves Harry.

Fucking goddamn Harry.

The Office

I returned from Miami on Christmas Eve to the usual turmoil.

-Returned to where?

To Paris. To Sandler & Son, our bombastic office in the Rive Droite.

-This Harry, he’s your father? Your boss?

Neither. Partner and mentor, maybe. He calls himself Harry Sandler and I’m Nicky Sandler—Harry passes me off as the son he had before admitting his sexual nature, since he’s not fooling anyone for long.

Harry fell head over heels for our office building on the Boulevard de Sebastopol the instant he laid eyes on it. Taste? No such thing. The building is a monstrosity, bulging into traffic, squatting like a Lumiere moon rocket just bursting to launch. But attention? Oh yes—you’re allowed no other choice. Buff and black, a riot of cornices and pediments, ornamental discs carrying no inscription, heroic statues with no recognizable subject and porthole windows puncturing the bulbous dome, just because. The perfect setting for a business with no legitimate means of support.

“Nicky! Welcome back!”

“Lucien D’Reaux called. His appraiser fingered the Modigliani as a fake.”

“Who let him get his own appraiser? Call him back, tell him we found another signature under the frame.”

“He knows it’s fake!”

“It’s a fake Modigliani; tell him it’s a real Elmyr De Hory.”

“It is?”

“No of course it’s not but De Hory’s the only art forger anyone’s heard of—hopefully we can cover the costs. And get someone good to fake the signature this time. What else’ve we got?”