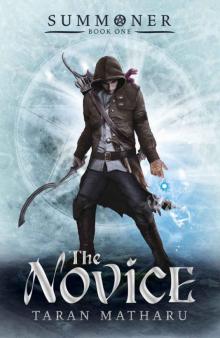

Summoner: Book 1: The Novice

Taran Matharu

Contents

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Copyright

If you liked this you’ll love . . .

1

It was now or never. If Fletcher didn’t make this kill, he would go hungry tonight. Dusk was fast approaching and he was already running late. He needed to make his way back to the village soon, or the gates would close. If that happened, he would either have to bribe the guards with money he didn’t have or take his chances in the woods overnight.

The young elk had just finished rubbing its antlers against a tall pine, scraping the soft velvet that coated them to leave the sharp tines beneath. From its small size and stature, Fletcher could tell it was a juvenile, sporting its first set of antlers. It was a fine specimen, with glossy fur and bright, intelligent eyes.

Fletcher felt almost ashamed to hunt such a majestic creature, yet he was already adding up its value in his head. The thick coat would do well when the fur traders came by, especially as it was now winter. It would probably make at least five shillings. The antlers were in good condition, if a little small, they might fetch four shillings if he was lucky. It was the meat he craved the most, gamy red venison that would drip sizzling fat into his cooking fire.

A thick mist hung heavy in the air, coating Fletcher in a thin layer of dew. The forest was unusually still. Normally the wind rattled the branches, allowing him to stalk through the undergrowth unheard. Now he barely allowed himself to breathe.

He unslung his bow and nocked an arrow to it. It was his best arrow, the shaft straight and true, the fletching from good goose feathers rather than the cheap turkey feathers he bought in the market. He took a shallow breath and drew back on the bowstring. It was slippery on his fingers; he had coated it in goose-fat to protect it from the moisture in the air.

The point swam in and out of focus as he centred it on the elk. Fletcher was crouched a good hundred feet away, hidden in the tall grass. A difficult shot, but the lack of wind brought its own rewards. No gust to jar the arrow in its flight.

He breathed and shot in one fluid motion, embracing the moment of stillness in body and mind that he had learned from bitter and hungry experience. He heard the dull thrum of the bowstring jarring and then a thud as the arrow hit home.

It was a beautiful shot, taking the elk through the chest, into the lungs and heart. The animal collapsed and convulsed, thrashing on the ground, its hooves drumming a tattoo on the earth in its death throes.

He sprinted towards his prey and drew a skinning knife from the slim scabbard at his thigh, but the stag was dead before he got to it. A good clean kill, that’s what Berdon would have said. But killing was always messy. The bloody froth bubbling from the elk’s mouth was testament to that.

He removed the arrow carefully and was happy to see the shaft had not snapped, nor had the flint point chipped on the elk’s ribs. Although he was Fletcher by name, the amount of time he spent binding his arrows frustrated him. He preferred the work Berdon would occasionally give him, hammering and shaping iron in the forge. Perhaps it was the heat, or the way his muscles ached deliciously after a hard day’s work. Or maybe it was the coin that weighed down his pockets when he was paid afterwards.

The young elk was heavy, but he was not far from the village. The antlers made for good handholds, and the carcass slipped easily enough over the wet grass. His only concern would be the wolves or even the wildcats now. It was not unknown for them to steal a hunter’s meal, if not his life, as he brought his prize back home.

He was hunting on the ridge of the Beartooth Mountains, so called for their distinctive twin peaks that looked like two canines. The village lay on the jagged ridge between them, the only path up to it on a steep and rocky trail in clear view from the gates. A thick wooden palisade surrounded the village, with small watchtowers at intervals along the top. The village had not been attacked for a long time, only once in Fletcher’s fifteen years in fact. Even then, it had been a small band of thieves rather than an orc raid, unlikely as that was this far north of the jungles. Despite this, the village council took security very seriously, and getting in after the ninth bell was always a nightmare for latecomers.

Fletcher manoeuvred the animal’s carcass on to the thick grass that grew beside the rocky path. He didn’t want to damage the coat; it was the most valuable part of the elk. Furs were one of the few resources the village had to trade, earning it its name: Pelt.

It was heavy going and the path was treacherous underfoot, even more so in the dark. The sun had already disappeared behind the ridge, and Fletcher knew the bell would be sounding any minute. He gritted his teeth and hurried, stumbling and cursing as he grazed his knees on the gravel.

His heart sank when he reached the front gates. They were closed, the lanterns above lit for their nightlong vigil. The lazy guards had closed up early, eager for a drink in the village tavern.

‘You lazy sods! The ninth bell hasn’t even rung yet.’ Fletcher cursed and let the elk’s antlers fall to the ground. ‘Let me in! I’m not sleeping out here just because you can’t wait to drink yourselves stupid.’ He slammed his boot into the door.

‘Now, now, Fletcher, keep it down. There’s good people sleeping in here,’ came a voice from above. It was Didric. He leaned out over the parapet above Fletcher, his large moonish face grinning nastily.

Fletcher grimaced. Of all the guards who could have been on duty tonight, it had to be Didric Cavell, the worst of the bunch. He was fifteen, the same age as Fletcher, but he fancied himself a full-grown man. Fletcher did not like Didric. The guardsman was a bully, always looking for an excuse to exercise his authority.

‘I sent the day-watch off early tonight. You see, I take my duties very seriously. Can’t be too careful with the traders arriving tomorrow. You never know what kind of riffraff will be sneaking about outside.’ He chuckled at his jibe.

‘Let me in, Didric. You and I both know that the gates should be open until the ninth bell,’ said Fletcher. Even as he spoke he heard the bell begin its sonorous knell, echoin

g dully in valleys below.

‘What was that? I can’t hear you,’ yelled Didric, holding a hand up to his ear theatrically.

‘I said let me in, you dolt. This is illegal! I’ll have to report you if you don’t open the gates this minute!’ he shouted, flaring up at the pale face above the palisade.

‘Well you could do that, and I certainly wouldn’t begrudge you your right to. In all likelihood we would both be punished, and that wouldn’t do anyone any good. So why don’t we cut a deal here. You leave me that elk, and I save you the trouble of sleeping in the forest tonight.’

‘Shove it up your arse,’ Fletcher spat in disbelief. This was blatant blackmail.

‘Come now, Fletcher, be reasonable. The wolves and the wildcats will come prowling, and even a bright campfire won’t keep them away in the winter. You can either leg it when they arrive, or stay and be an appetiser. Either way, even if you do last until morning, you’ll be walking through these gates empty-handed. Let me help you out.’ Didric’s voice was almost friendly, as if he was doing Fletcher a favour.

Fletcher’s face burned red. This was beyond anything he had experienced before. Unfairness was common in Pelt, and Fletcher had long ago accepted that in a world of haves and have-nots, he was definitely the latter. But now this spoiled brat, a son to one of the richest men in the village no less, was stealing from him.

‘Is that it then?’ Fletcher asked, his voice low and angry. ‘You think you’re very clever, don’t you?’

‘It’s just the logical conclusion to a situation in which I happen to be the beneficiary,’ Didric said, flicking his blond fringe from his eyes. It was well known that Didric was privately tutored, flaunting his education with flowery speech. It was his father’s hope that he would one day be a judge, eventually going to a lawhouse in one of the larger cities in Hominum.

‘You forgot one thing,’ Fletcher growled. ‘I would much rather sleep out in the woods than watch you take my kill.’

‘Hah! I think I’ll call your bluff. I’ve a long night ahead of me. It will be fun to watch you try and fend off the wolves,’ Didric laughed.

Fletcher knew Didric was baiting him, but it didn’t stop his blood boiling. He gulped the anger down, but it still simmered at the back of his mind.

‘I won’t give you the elk. There’s five shillings in the fur alone, and the meat will be worth another three. Just let me in, and I’ll forget about reporting you. We can put this whole thing behind us,’ Fletcher suggested, swallowing his pride with difficulty.

‘I’ll tell you what. I can’t come away completely empty-handed – that wouldn’t do now would it? But since I’m feeling generous, if you give me those antlers you neglected to mention, I’ll call it a night, and we can both get what we want.’

Fletcher stiffened at the nerve of the suggestion. He struggled for a moment and then let it go. Four shillings were worth a night in his own bed, and to Didric it was nothing but pocket change. He groaned and took out his skinning knife. It was razor sharp, but it was not designed for cutting through antlers. He hated to mutilate the elk, but he would have to take its head.

A minute later and with some sawing at the vertebrae, the head was in his hands, dripping blood all over his moccasins. He grimaced and held it up for Didric to see.

‘All right, Didric, come and get it,’ Fletcher said, brandishing the grisly trophy.

‘Throw it up here,’ said Didric. ‘I don’t trust you to hand it over.’

‘What?’ cried Fletcher in disbelief.

‘Throw it up now or the deal is off. I can’t be bothered to wrestle it from you and get blood all over my uniform,’ Didric threatened. Fletcher groaned and hurled it up, spattering his own tunic with blood as he did so. It flew over Didric’s head and clattered on the parapet. He made no move to get it.

‘Nice doing business with you, Fletcher. I’ll see you tomorrow. Have fun camping in the woods,’ he said cheerily.

‘Wait!’ shouted Fletcher. ‘What about our deal?’

‘I held up my end of the bargain, Fletcher. I said I’d call it a night, and we’d both get what we want. And you said earlier you would rather sleep in the woods than give me your elk. So there you go, you get what you want, and I get what I want. You really should pay attention to the wording in any agreement, Fletcher. It’s the first lesson a judge learns.’ His face began to withdraw from the parapet.

‘That wasn’t the deal! Let me in, you little worm!’ Fletcher roared, kicking at the door.

‘No, no, my bed is waiting for me back at home. I can’t say the same for you, though,’ Didric laughed as he turned away.

‘You’re on watch tonight. You can’t go home!’ yelled Fletcher. If Didric left his watch, Fletcher could get his revenge by reporting him. He had never considered himself a snitch, but for Didric he would make an exception.

‘Oh, it’s not my watch,’ Didric’s voice shouted faintly as he descended the palisade steps. ‘I never said it was. I told Jakov I’d keep an eye out while he used the privy. He should be back any minute.’

Fletcher clenched his fists, almost unable to comprehend the extent of Didric’s deceit. He looked at the headless carcass by his ruined shoes. As the fury rose up like bile in his throat, he had only one thought in his mind. This was not the end of it. Not by a long shot.

2

‘Get out of bed, Fletcher. This is the only time of year I actually need you up on time. I can’t mind the market stall and shoe the packhorses at the same time.’ Berdon’s ruddy face swam into view as Fletcher opened his eyes.

Fletcher groaned and pulled his furs over his head. It had been a long night. Jakov had made him wait outside for an hour before he let him in, on the condition that Fletcher bought him a drink next time they were in the tavern.

Before Fletcher had a chance to bed down, he had to gut and skin the elk, as well as trim the meat and hang it by the hearth to dry. He only allowed himself one juicy slice, half cooked on the fire before he lost patience and crammed it into his mouth. In the winter it was always best to preserve the meat for later; Fletcher didn’t know when his next meal was coming at the best of times.

‘Now, Fletcher! And clean yourself up. You stink like a pig. I don’t want you driving customers away. Nobody wants to buy from a vagrant.’ Berdon yanked his furs away and strode out of Fletcher’s tiny room at the back of his forge.

Fletcher winced at the loss of his covers and sat up. His room was warmer than he had expected. Berdon must have been at the hot forge all night, preparing for trading day. Fletcher had long ago learned to sleep through the clanging of metal, the roar of the bellows and the sizzle as the red-hot weapons were doused.

He trudged through the forge room to the small well outside, where Berdon drew his dousing water. He hauled up the bucket and, with only a moment’s hesitation, poured the freezing water over his head. His tunic and trousers were soaked as well, but since they were still covered in blood from the night before, it would probably do them some good. Several more bucketfuls and a brisk scrub with a pumice stone later, Fletcher was back in the forge room, shivering and clutching his arms to his chest.

‘Come on then. Let’s have a look at you.’ Berdon stood in the doorway to his own room, the light from the hearth illuminating his long red hair. He was by far the largest man in the village, long hours of beating metal in his forge giving him broad shoulders and a barrel-like chest. He dwarfed Fletcher, who was small and wiry for his age.

‘Just as I thought. You need a shave. My aunt Gerla had a thicker moustache than that. Get rid of that wispy fuzz until you can grow a real one, like mine.’ Berdon’s eyes twinkled as he twirled the red handlebar that bristled above his grizzled beard. Fletcher knew he was right. Today the traders were coming, and they would often bring their city-born daughters with their long pleated skirts and ringleted hair. Though he

knew from bitter experience that they would turn their noses up at him, it wouldn’t hurt to be at least presentable today.

‘Off you go. I’ll lay out the clothes you’re going to wear whilst you shave. And no complaints! The more professional you look, the better our merchandise does.’

Fletcher trudged back outside into the freezing cold. The forge lay right by the village gates, with the wooden palisade edge just a few feet from the back wall of Fletcher’s room. A mirror and small washbasin lay discarded nearby. Fletcher removed his skinning knife and trimmed away the fledgling black whiskers, before scrutinising his face in the mirror.

He was pale, which was not surprising this far north in Hominum. The summers were short in Pelt, with a brief but happy few weeks spent with the other boys in the forest, tickling trout in the streams and roasting hazelnuts by the fire. It was the one time when Fletcher did not feel like an outsider.

His face was harsh, with sharp cheekbones and dark brown eyes that were slightly sunken. His hair was a thick, shaggy mess of black, which Berdon would literally shear when it got too wild. Fletcher knew he was not ugly, but nor was he handsome compared to the rich, well-fed boys with ruddy cheeks and blond hair who populated the village. Dark hair was unusual in the northern settlements, yet since he had been abandoned in front of the gates as a baby, Fletcher was not surprised he looked nothing like the others; just another thing to set him apart from the rest.

When he returned, Fletcher saw Berdon had laid out a pale blue tunic and bright green trousers on his bed. He blanched at the colours but swallowed his comments when he saw Berdon’s remonstrative stare. The clothes would not look unusual on trading day. Traders were well known for their flamboyant garb.

‘I’ll let you get dressed,’ said Berdon with a chuckle, ducking out of the room.

Fletcher knew that Berdon’s teasing was his way of being affectionate, so he didn’t let it get to him. He had never been the talkative type, preferring his own company and thoughts. Berdon had always been respectful of his privacy, ever since he had been first able to speak. It was a strange relationship, the gruff, good-natured bachelor and his introvert apprentice, yet they made it work somehow. Fletcher would always be grateful that Berdon took him in, when nobody else would.