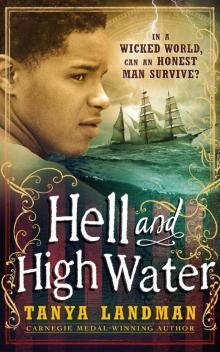

Hell and High Water

Tanya Landman

Contents

PART 1

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

PART 2

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

PART 3

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

To Rod Burnett, for endless creative inspiration

PART 1

1.

The city of Torcester.

High summer.

Market day.

Thronging streets; honest men mingling with thieves, clergymen with vagabonds, gentry with peasants, housewives with whores. The noise, the jostling of so many people in the narrow lanes! Sweat and shit, pies and ale, unwashed bodies, horses – the combined stench worked like a draught of the finest spirits on Joseph Chappell. His eyes shone, his breath came faster, the blood raced through his veins.

Caleb watched his father pushing the handbarrow through the crush with bemused envy. He shared neither Pa’s fair skin, nor his tastes or temperament: he loathed the city. Only when they were far away from people and their constant, invasive curiosity was he truly comfortable. A quiet valley with rolling hills, an open stretch of moorland – these were his favourite haunts. But no money was to be made in such places. A winding river, an expanse of purple heath might please the eye but pleasant views, Pa said, did not pay for meat or ale. It was true enough, and yet Caleb knew there was something else that drew them to Torcester so often. The fact was inescapable – Joseph may have been born the son of an earl, bred to a life of idleness and luxury, but at heart he was a showman, and a showman cannot live without a crowd.

Pa took his favourite spot on the cobbles beside the cathedral’s green. As soon as he saw them the bishop of Torcester crossed the grass, a welcoming smile on his face. He might be a man of God, but he liked a good belly laugh as much as any common sinner. First nodding to Caleb, the bishop then took Pa’s right hand in both of his, shaking it with such enthusiasm that Pa’s fingers were in danger of being crushed.

“Well met, Mr Chappell,” the bishop said. “Well met indeed!” He lowered his voice to a theatrical whisper. “And what antics shall we have today?”

“Many and various, as always.”

“And shall the Devil finally carry Mr Punch to hell as the old sinner deserves?” the churchman asked, winking.

“I fear not,” replied Joseph with mock regret. “He must sin, and sin again, or what should I have to live on?”

“What indeed?” The bishop threw back his head and laughed. “We both depend on sinners to earn an honest living, do we not?” Clapping Pa on the shoulder, the bishop went on his way, but Caleb knew he would be back when the entertainment began, for the churchman was a great admirer of Pa’s skill. This last winter Joseph had carved new puppets and built a new stage for them and each time the bishop watched he was in raptures about Pa’s ingenuity, questioning him long and hard about the theatre’s frame, wanting to know how Pa had got the idea, how he’d managed to build it, whether he’d done it all himself or employed a craftsman – the man’s curiosity was boundless!

Caleb helped Pa set up the show. When Joseph judged there were sufficient people milling about by the green he rang a handbell to gain their attention and announced that the first performance would commence very shortly. Sure enough, the bishop took his place before Pa had even finished speaking.

The first performance went smoothly, as did the second that followed an hour or so after. A short break for Pa to get his breath back and quench his thirst and then on to the third and fourth of the day. Each time the crowds grew larger.

At last they came to the fifth and final show. Joseph was more than halfway through, Caleb standing at the side watching the hangman, Jack Ketch, slowly explaining the process of death-by-hanging to Mr Punch. Once, twice, he’d told the grinning hunchback what to do and once, twice, Punch had got it wrong. Jack was now giving the instruction for the third time.

“You put your head in here. Look, see?” Jack opened the noose wide. “And then you have to say ‘I’ve been a very wicked man. I’m sorry I done it!’ And then I pull that knob there.”

Once more Punch slowly approached the noose. Last time he’d ducked to the right, missing it by an inch and giving the playboard a loud whack with his hooked red nose. This time he ducked to the left. There were shrieks of delight from the crowd, the bishop laughing loudest of all.

“No!” screamed Jack Ketch. “You dolt! You simpleton! You’re a very foolish man! And because you’re so foolish I’m going to have to show you. You do it like this. You put your head in here, see?” Jack Ketch, the hangman, slid his head through his own open noose.

“You put your head in here,” repeated Punch.

“That’s right. You say, ‘I’ve been a very wicked man.’”

“I’ve been a very wicked man,” Punch repeated obediently.

“I’m sorry I done it!”

“I’m sorry I done it!” wailed Punch.

“That’s right,” said Jack. “But don’t over-act. And then I pull that knob there.”

“And then I pull that knob there.” Punch darted from one side of the stage to the other. The outcome was totally predictable, but that was the joy of it. Pa always said that anticipation was the greatest part of comedy.

“No! Don’t pull the knob!” screeched Ketch.

Alas! Too late…

Punch pulled it, tightening the noose, and the hangman began making ghastly choking noises. When he eventually fell silent Punch said, “Are you dead yet?”

“No. I’m not.” More ghastly choking followed. Joseph always knew precisely how long he could draw out the thread of a joke before it snapped and today the crowd was in a mood to see the hangman suffer. By the time the puppet finally fell down dead they were convulsed. Snot flowed down the face of a lad in the front who didn’t have so much as a sleeve to wipe it on. A fine gentleman at the back pressed a silk handkerchief to his face to smother the stink of the common folk who were now stamping their feet, yelling and roaring for more, more! They were hungry – ravenous – for Punch’s outrageous antics and, ever the showman, Pa was delighted to satisfy them.

Punch picked the hangman up and threw him over the playboard where he dangled, wooden and lifeless, just over the heads of the children who had gathered by the front of the show. They reached out, trying to seize the puppet, but before they could Punch took up the gallows and whirled Jack Ketch at the end of his rope full circle once, twice, thrice before throwing gallows, hangman and all down into the theatre and out of sight. Then he bobbed back up to the stage grinning, clapping his hands, shrieking, “That’s the way to do it!”

Caleb scanned the crowd. Timing is everything: Pa had told him often enough. He was talking about his own performance but it applied equally well to Caleb’s part in things. He picked up the bottle. Pa had discovered long ago that a hat was too easy for a light-fingered thief to remove coins from. “They’ll put in a farthing, take out a shilling.” But once a penny was dropped down the neck of a leather bottle no one but Pa could remove it.

&nb

sp; Caleb watched the watchers with a knot tightening in his belly, fearing that he’d pick the wrong moment, that he’d walk past the open-handed and approach only the tight-fisted. People were so hard to judge! Now, he hoped, was a good moment. He’d go round again later once Punch had beaten the Devil, but right now the pieman on the left was about to move off. He had to be good for a farthing or two, didn’t he? As did the big-bosomed flower-seller next to him who was rocking with laughter. And the ginger-haired youth close by? He was barefoot and clad in tatters. Though he was watching the puppets intently Caleb didn’t feel he could ask someone so obviously destitute for money. No … he’d give the lad a wide berth.

The fine gent was a different matter, though – he could afford to give, and give generously. Caleb would save him for last. Once the show was over and Punch had beaten the Devil – that would be the time. Gentry kept the strings of their purses tightly tied. It was how the rich stayed rich, Pa said: by never giving anything away. But after Punch’s grand finale maybe this one would contribute a little something? As for the bishop, it was best to let him watch the Devil being sent back down to hell before asking him. He never liked to have his entertainment interrupted.

Clearing his throat, Caleb yelled, “Any money for Mr Punch?”

The pieman had been about to go on his way but when Caleb rattled the bottle he stopped, reaching into his pouch and pulling out a couple of pennies to drop down its neck. The flower seller was next. She ruffled Caleb’s hair so violently it sent ripples across her gigantic bosom.

“Woolly as a sheep,” she giggled. “Does your master shear you in the spring?”

Caleb winced. Her teasing was nothing he hadn’t heard before and yet the words cut deep. He smiled as best he could and gave the answer he was used to trotting out in such situations. “Why yes he does. A quality fleece, is it not? He has to make a penny where he can.” Pa had always advised him to turn aside foolish remarks with a joke of his own. It was a decent enough quip and one he’d used several times before, but he still felt the colour rising in his cheeks. It was fury, not embarrassment, but the flower seller misunderstood the cause.

“Lord love him, look at that! I never knew darkies could blush. He’s gone purple as a plum!”

Had Caleb been generously rewarded it might have been more bearable, but she dropped only a single farthing into the bottle before sending him on his way with a bruising pinch on the arse. He was too angry to approach anyone else and strode back to the side of the theatre just as the Devil rose from its bowels, appearing on the stage and bellowing, “I’m coming to get you!”

Punch was trembling behind the curtain, but his hiding place was betrayed by the children, pointing, shouting out, some now so excited that they were in danger of pissing themselves.

“I am Satan,” boomed Pa. He sounded barely human. “I am Beelzebub! I am the Devil.”

Eternal damnation loomed but was Punch afraid?

“The Devil? Oooooh! I married your sister,” he said saucily.

Caleb laughed. That was a new one, made up on the spur of the moment. He must tell Pa to keep it in the show. The joke made the bishop chuckle so much his broad belly quivered.

“I have come to take you down to hell,” roared the Devil.

“I don’t want to go.”

“Then we’ll have to fight. And the winner takes all…”

Cheering Punch, jeering the Devil, the crowd’s heads snapped from side to side in unison as the fight went back and forth.

It was nearly time. Caleb knelt on the cobbles behind the theatre, striking Pa’s tinderbox and lighting the hellfire flame’s candle.

It was a simple device: a pewter pot, small enough to cup in the palm of one hand, with a lid, punctured with holes, on top of which stood the candle. A tube fed into the side like the stem of a pipe.

Caleb listened, poised and ready. When Punch’s slapstick finally cracked once, twice, thrice over the Devil’s head both his horns would come flying off into the crowd, making them shriek with wild excitement. Now! Shielding the flame with his hand, Caleb carefully passed the pipe through the folds in the theatre’s cloth cover, hoping and praying that the candle wouldn’t snuff out.

As Mr Punch threw the Devil through the gates of hell, Pa blew down the pipe’s tube. A cloud of the powdered resin contained in the pewter pot now billowed into the air, igniting as it passed through the candle’s flame. The crowd saw a great ball of hellfire burst through the open top of the theatre, followed by coiling black plumes of smoke, and cried aloud with wonder. Caleb grinned at their noise: it was always a delight. Such a simple piece of trickery, but so very dramatic!

His task backstage completed, he darted round to the front. When Punch came up to take his final, triumphant bow, Caleb took off again with the bottle, weaving between the watchers, “Any money for Mr Punch?”

The fine gent had watched the show, beginning to end. Admittedly, he had not laughed much: his expression had remained sour, his mouth pinched. But a man’s face does not always show what is in his mind. Caleb headed first for him, calling out, shaking the bottle. He came to a halt in front of the gentleman but it was as though Caleb was a creature made of light and air, for the man looked right through him. How very skilled the aristocracy are when it comes to ignoring lesser mortals, Caleb thought. Where do they learn such tricks?

No matter. He turned away. The bishop’s generosity made up for the gentleman’s lack of it and others in the crowd gave as freely as they could. By the time everybody had dispersed, the bottle was full of money – plenty enough to keep Caleb and Pa fed until next market day.

Emerging hot and sweating from the theatre, Pa took the bottle and shook some coins out into Caleb’s hands.

“A good day, but a long one!” he said with a smile. “I feel half-starved, and no doubt you’re the same. If I don’t eat soon I’ll be swooning like a lady. Go get us a pie from Porlock’s. Tell Mrs P we’ll be along later, when we’ve packed the show down. Ask her to put on a fresh pot.”

Caleb sighed but did as he was told, weaving through the streets to Porlock’s Coffee House. Here was another topic on which his opinion differed from Pa’s.

Porlock’s was a meeting place where businessmen discussed commerce and learned men from the city’s university sat and debated. Joseph had no interest in the former, but he loved to join the latter in talking of philosophy and politics. Such things bored Caleb almost to tears and, in addition to the tedium, he often had to endure remarks from men who took him to be Pa’s slave, not his son. Engrossed in conversation, Pa – usually so quick to shield him – rarely noticed these slights. Caleb associated Porlock’s with discomfort, although even he had to admit that their mutton pies were the best to be had in Torcester.

He was returning to the green with two of them. From ten yards away he could see that Pa had already packed his puppets and was starting to dismantle the theatre when there was the cry, “Stop thief!”

Both Pa and Caleb swung round.

A slap of running feet. Yells. Noises of pursuit.

Then the ginger-haired youth, clad in tatters, darted over the cobbles towards the cathedral. As he passed, he hit Pa in the belly. Thumped him so hard that Pa doubled over, clutching his gut, groaning with shock and pain.

Dropping the pies, Caleb ran to him, so concerned for Pa that he did not even notice the fine silk purse that had fallen at his father’s feet.

2.

Joseph was bent over, winded, his eyes fixed on the ground. When he had recovered his breath a little he stood, but not before he’d reached out a hand for what lay at his feet.

The moment Pa picked up the purse their lives began to unravel. Two constables rounded the corner and saw him holding it. Joseph Chappell was caught red-handed, so they said.

Congratulating themselves on the remarkable speed with which they’d solved the crime, they seized him, grabbing him by the arms, forcing his hands behind his back, pushing his wrists up so hard that he cried out. Pa

was unable to resist. When Caleb tried to pull the constables off, he was struck. A savage blow under his chin threw him back onto the ground, smashing his head against the cobbles.

The owner of the purse – the very same fine gentleman who had watched the show and put nothing in the bottle – was called forward. He confirmed the thing was his and that was that. The constables started to pull Pa away and when he tried to protest he was knocked almost senseless. They dragged him between them, his blood dripping onto the street.

Caleb, struggling to his feet, made a move to follow but Pa managed to say, “Stay… The show…”

To abandon the newly made theatre and the puppets that his father had carved with such care was unthinkable. Caleb was left, head and jaw aching, standing alone looking about stupidly for the culprit, but the ginger-haired thief had disappeared. It had happened so quickly! There must be someone – a friendly face, a kindly soul who might intervene on Pa’s behalf. The bishop? No … he was gone, along with the rest of the crowd. There was nothing but a motley collection of indifferent passers-by.

Cold, blind panic made Caleb’s limbs so heavy he couldn’t move and his throat so tight that he struggled to breathe. But he couldn’t just stand here like a statue! There was work to be done. As swiftly as he could he finished the job Pa had barely started. Removed the cloth cover. Dismantled the theatre. Collapsed the frame. Pa’s new system made it a work of minutes. He rolled it up in its cover, then wrapped the whole in a length of sacking, tying the bundle tight before loading it and the puppets onto the handbarrow. Once the task was complete he sat and waited for Pa’s return.

He would be back. Of course he would. This was a mistake. The constables would find they were wrong and set Pa free. He would come striding across the green, cursing their idiocy, laughing at Caleb’s distress. He would take the handles of the barrow and push it ahead of him effortlessly over the cobbles as he always did. They would leave Torcester. Soon. Soon.

The night, if slept through in a fine feather bed, lasts no time at all. There had been occasions when Caleb had lain down, shut his eyes and, seemingly in one breath, the dawn had come. Yet now, sitting awake, riddled with fear, that single night lasted for years.