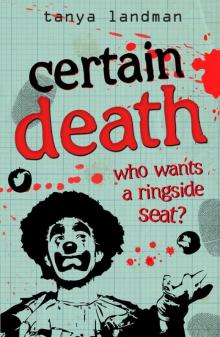

Certain Death

Tanya Landman

For Sally and Nigel:

true artistes

An explosion tore the night apart. Rifle fire answered a hail of mortars. Glass shattered. Buildings fell. Screams were drowned by a fresh wave of shelling.

On the hill above the town a ragged figure cowered behind a rock, terrified, desperate thoughts crashing so hard against each other that they seemed louder than the fighting below. Move. Get away. Now! Over the mountains. Across the border. Sleep? No! No rest. No food. Escape! Leave the horror. Blood. Fear. Stink of death. Leave it behind. Dead! So many dead! The men. Shot. Gone. All gone. Who is fighting now? Women? Children? Will the battle rage until the whole town is slaughtered?

Keeping low to the ground the figure moved, scurrying from rock to rock like a frightened rodent evading a bird of prey.

The world is big. Find somewhere. Make a new home. A new beginning. A fresh start. Go. Now. Go!

the circus is

coming to town

My name is Poppy Fields. I’m not very keen on circuses. I’m not saying that the performers aren’t talented – I mean, there aren’t many people who can juggle and unicycle and eat fire; fewer still can walk a tightrope or turn a somersault or dangle ten metres above the ground suspended by their teeth. So you have to admire people who can. The trouble is, I don’t quite see the point of it all. It’s not like there’s a riveting storyline to follow. As far as I can see, a circus is just a load of people in spangly leotards showing off.

So when Brady Sparkles’s outfit came to town, why was I practically elbowing old ladies out of the queue so that Graham and I could get front-row seats?

It was because this particular circus was offering its audience something completely different. The posters promised that the first performance would end in Certain Death.

The advance publicity had started appearing two weeks before the circus arrived. It was the same every year: the caravans and lorries would always pitch up at our local park on the last Friday before the summer half-term holiday. They’d erect the big top (a pretty spectacular event in itself) and then do three days of performances, beginning with a Saturday matinee. My mum had taken me years ago, but we hadn’t been back since: one afternoon being blinded by cheesy grins and tangerine tans was enough as far as I was concerned.

So on the way to Graham’s house I walked straight past the first poster without giving it so much as a glance. But a second one had been stuck on the wall of the bus shelter, and I ended up reading it while we waited for the bus to school.

WORLD PREMIERE! It screamed. DEBUT PERFORMANCE!!! NEVER BEFORE SEEN!!!!! IRENA, THE FLYING BALLERINA, PRESENTS HER HEART-STOPPING NEW ACT!!!!!!

“Whoever wrote that should be prosecuted for reckless use of exclamation marks,” I said. “Talk about squandering the planet’s resources. There’ll be a worldwide punctuation shortage if they’re not careful.”

Graham flashed one of his blink-and-you-miss-it grins. I turned back to the poster and read the last line.

WITHOUT A SAFETY NET, IRENA DEFIES GRAVITY AND FACES ALMOST CERTAIN DEATH!!!!!!!!

Or at least that was what it was supposed to say. But someone had taken a black marker to it and crossed out the word “almost”.

“Look at that,” I said, pointing.

“Someone’s idea of a joke, presumably,” Graham replied with a shrug.

I wasn’t so sure. “I don’t think so,” I said, peering at it more closely. I mean, posters are always being defaced in that bus shelter. But people usually draw moustaches or scrawl their names or write rude words. This was different. Whoever had done it must have been pretty angry – they’d pressed so hard that they’d wrecked the pen, you could see a splodge of ink where the felt tip had collapsed. Then I noticed something even more odd.

“That line’s dead straight,” I said.

“Do you think that has some sort of significance?” asked Graham.

“Yes, I do,” I answered thoughtfully. “How many vandals do you know who bother to use a ruler?”

The third poster was on the school noticeboard and

I was drawn to it like a magnet. When I saw the same heavy black line through the word “almost”, I felt a prickle of concern.

“That poster,” I said to Mrs Cook, the school secretary.

“Which one?” she replied, looking harassed as usual.

“Brady Sparkles’s Circus. It’s been drawn on.”

“Has it, dear? I hadn’t noticed.”

“So you don’t know who did it?”

“No, I’m afraid not. Does it matter?”

“Who gave it to you?” I asked.

“Some man from the circus,” Mrs Cook said. “He offered half-price tickets for the staff if I put it up.”

“But you don’t know if it was already marked like that when you stuck it on the board?”

“No dear, sorry.”

By now I was holding up a queue of people who wanted to pay their lunch money or hand in permission slips for school trips, so I couldn’t pursue it further. Not that Mrs Cook had any more to tell me. In fact, all the grown-ups we talked to over the next couple of weeks proved to be amazingly unobservant. Graham and I hunted down posters like a pair of sniffer dogs, and each and every one we found was marked in the same way. What we couldn’t discover was whether they’d been tampered with before they’d been put up, which would probably mean someone in the circus had done it, or afterwards, in which case someone in the town must have a pretty warped sense of humour. We tried asking in the shops that displayed posters, but all the conversations we had went pretty much the same as the one I’d had with Mrs Cook.

“Your poster’s been drawn on.”

“Has it? Oh yes.”

“You didn’t see anyone do it?”

“No. Certain death, eh? Sounds exciting. Maybe I’ll take the kids.”

The day before the circus was due to arrive, the local newspaper ran a big feature on it. There was a double-page spread showing photographs of Peepo, a mad-looking clown with a big moustache who would be running circus-skills workshops between performances; the Dashing Blade, a knife-thrower who wore alarmingly thick glasses; Alonzo and the Bouncing Bellinis, a troupe of exceedingly springy acrobats; and Carlotta, a lady who did something bizarre with a hula hoop. But pride of place had been given to Irena, who I suspected was actually quite pretty under the heavy make-up. It seemed that Irena and Alonzo (who had a scarily hairy chest) had developed a new act together, and the caption under their photo declared in big black letters that when they premiered it on Saturday, Irena would face Certain Death.

“Do you think the journalist has made a mistake?” I said to Graham. “A typing error or something?”

“I don’t think the article was written by someone at the paper,” Graham replied. “Look – it says at the top of the page that it’s an Advertisement Feature.”

“What does that mean?”

“As I understand it, the circus will have paid for it to go in – it’s a glorified advert. They’ll have provided all the words and pictures.”

“So someone must have tampered with the wording before it was sent in to the newspaper?” I asked. Graham nodded. “In that case it has to be someone in the circus. No one else could have done it, could they?”

“I believe not,” Graham agreed.

“Do you reckon it’s a joke? Or is someone really planning to kill Irena?”

“Oh dear. Here we go again.” Graham looked at me, sighed wearily and said, “I suppose you want us to find out.”

the big top

The best way to discover what was going on at the circus was to get inside it, so signing up for Peepo’s skills workshops seemed to be the perfect solution. Mum was extremely suspicious of my new-found enthusiasm. When I mentioned

that I wanted to learn juggling, her eyes narrowed into interrogatory little slits.

“I thought you hated the circus. Last time I took you, you whinged all the way through. You screamed at the acrobats and cried when the clowns came out.”

“I was only six.”

“Even so… When you weren’t screaming you were yawning. I thought you were going to die of boredom by the end. What’s brought this on?”

“It’s Graham’s idea,” I said quickly.

“Graham? He doesn’t strike me as the circus type.”

“Ah, well … he’s very interested in the physics behind the weight-to-speed ratio of juggling balls,” I lied.

I didn’t have a clue what I was talking about, but fortunately neither did Mum because she rolled her eyes and said, “Yes, that sounds like Graham. Well, I suppose it’ll keep you both occupied for half-term. And it’s not like we had anything else planned.” She pulled some cash from her purse. “Don’t spend it all at once.”

According to the local paper the very first workshop was on Friday at 4.30 p.m., which I reckoned would be pretty much straight after the big top had gone up. Graham and I caught the bus home from school but got off three stops earlier than usual, at the park.

The circus had arrived bang on schedule. Caravans and lorries were parked bumper to bumper around the edge of the football pitch, transforming the boring rectangle of grass into something exotic and colourful. Right in the centre the big top lay flat on the ground like a deflated beach-ball. There were barely any gaps between the vehicles, but to ensure the punters kept out, crush barriers had been erected around the whole area. It was like a new town had suddenly sprung up out of nowhere.

Now I might not have been mad keen on the idea of the performance, but I found the lives of the people housed in those mobile homes absolutely riveting. Studying human behaviour is a hobby of mine, so the idea of a travelling community that kept itself separate from the rest of the world was fascinating. It would be great if you all got on with each other, but suppose you didn’t? How awful would it be to be stuck with someone you couldn’t stand? It wasn’t like you could get away from anybody, not really. You’d be living and working shoulder to shoulder with them all day, every day. How stressful would that be? What might it drive you to do?

By the time Graham and I reached the bank overlooking the caravans, a crowd had gathered to watch the big top going up. The circus people – dressed in ordinary jeans and tracksuits – stood ready to begin.

The poles were winched into position with smooth, well-oiled ease. Then the swathes of canvas rose from the ground, and a spontaneous round of applause erupted from the watchers.

When the sides were finally looped together and the whole thing was secured firmly to the ground with guy ropes, some of the circus people disappeared back into their caravans and most of the watching crowd broke up and headed home. But Graham and I walked down to the gap in the crush barriers and told the huge bouncer patrolling the entrance that we were there for the workshop. He looked us up and down and then nodded us through, telling us to go and stand outside Peepo’s caravan, which had his name helpfully painted in big red letters across one side. We entered Circus Territory.

Before long, six other kids we’d never met before joined us, and after a mumbled round of hellos we stood in awkward silence waiting for Peepo to come out. Time ticked on.

A load of people were milling around near the big top, heaving various bits of equipment into place. I could see the Bouncing Bellinis and Carlotta, and I assumed the man giving orders was Brady Sparkles, the ringmaster. No one paid any attention to us.

At 4.35 p.m. Graham – who likes things to be done on time – stepped up to Peepo’s door and rapped on it sharply with his knuckles. There was no response. But two caravans down, there was a sudden bang. A door was flung open with a theatrical flourish and Irena appeared. Her hair was pulled back into a ponytail and there wasn’t a sequin in sight, but she looked dazzling.

She paused on the steps for a moment, looking around to check we’d noticed her before descending. Then she stalked in the direction of the big top. There was something mesmerizing about the way she moved – a powerful, dangerous grace that reminded me of the tigers Graham and I had recently encountered A Bit Too Closely for Comfort.

Just then, a small, wiry man whose top lip was weighed down by a fine crop of facial hair came out of the big top and limped towards us. He was carrying a bag of juggling balls, and although he didn’t have his make-up on it was obvious that this was Peepo.

When Peepo crossed Irena’s path, she stopped and wrinkled her nose as if she’d smelt something unpleasant. I’ve never seen anyone exude so much obvious distaste. She didn’t shout or swear at him; she didn’t even give him a withering look: it was worse than that. When Peepo said something to her – we were too far away to catch his words – she simply behaved as if he was invisible. He spoke again, looking at her pleadingly. If she’d turned away, it might have been kinder. But no – as far as she was concerned he simply wasn’t there. It might have looked childish, like a silly playground tiff, if she hadn’t had such a strong personality. You could feel the force of her rejection blasting across the grass like a small nuclear explosion.

Peepo didn’t try again. His shoulders dropped and he seemed to shrink under the weight of her dislike. He moved out of her way, his limp more pronounced as he came towards us, as if she’d physically wounded him. I felt a stab of anger towards Irena.

The contrast in her behaviour two seconds later must have been devastating for Peepo. Alonzo, naked from the waist up, stepped out of his caravan. Like Irena, he paused on the top of the steps for a moment. Hands on hips, he puffed out his chest so we could all admire how well-thatched it was. The smile that Irena threw him would have knocked a lesser man off his feet, but Alonzo caught it and sent it hurtling back – it was as if they were locked together in a lightning storm of mutual adoration.

Which was extremely interesting, I thought. Because the more Irena and Alonzo smiled at each other, their faces illuminated with happiness, the more the rest of the circus people glowered. The Bouncing Bellinis – three men and a woman – were stomping about near the big top with a surprising lack of acrobatic grace. Carlotta suddenly looked as though she would happily strangle Irena with her hula hoop. And Brady Sparkles was wearing an expression that my mum would have said could curdle milk.

At last, Peepo reached his group of eager pupils. He didn’t bother introducing himself and didn’t ask for any of our names, he simply took our money without a word and then, without any visible trace of enthusiasm, handed us each a ball.

“Only one?” queried Graham. “I thought we were going to learn juggling.”

“You begin with one,” growled Peepo in a thick Russian accent. “When you get that right, we move on to two balls, then three. Throw it from hand to hand, like this.” He demonstrated. “Throw it the same height every time. And catch it here, keeping your hand low, at the waist. Do not grab for the ball. Practise.”

It should have been a simple enough task but I was completely useless, mainly because my attention was elsewhere.

“No!” snapped Peepo, snatching the ball out of my hand. “See? Like this. The ball goes up and down in an arc, not forward and back. You do not throw it away from your body and then grab it! Listen to me. Do as I tell you.”

They must have finished getting the big top ready, because out of the corner of my eye I could see one of the Bouncing Bellinis sitting on the grass playing with a small child of about two or three. As I watched, she was joined by another member of the troupe. She said something to him and they both glanced over at Peepo with expressions that I couldn’t quite read. Suspicion? Dislike? Sympathy? Perhaps all three. I was dying to hear what they were saying.

There was nothing for it. Despite Peepo’s instructions, I threw my ball hard and high and made a deliberately ham-fisted attempt to catch it. I fumbled and accidentally-on-purpose whacked it in the di

rection of the acrobats. My aim was brilliant: it rolled under a caravan and I had to run after it and then crawl underneath. While I was retrieving it, I got to hear some of their conversation.

You’d have thought the Bellinis were Italian – they certainly looked it. But they sounded like they’d just walked off the set of EastEnders.

“Does Irena know what happened to the posters, Marco? Has she seen them?” asked the woman.

“Yes, she knows. Carlotta made sure of that.”

“Weird! Did Peepo do it?”

“He says he didn’t,” replied Marco.

“Wasn’t he the one who gave them out this time?”

“Yeah, but you know what it’s like, Francesca – they’re all rolled up. You don’t bother to undo them, do you?” He chewed his lip. “More likely to be Brady, I’d have thought. That kind of trick would be more his style.”

“He wouldn’t hurt her, though, would he?” asked Francesca.

“I don’t know. Irena’s really riled him. I’ve never seen him so angry. If he can’t hang on to her legally, I don’t know what he’ll do. He certainly doesn’t want her to leave.”

“More’s the pity!” sighed Francesca. “We’d be better off without her.”

“Not if she takes Alonzo with her, we won’t,” said Marco.

“I can’t believe he’d do that to us. Doesn’t family mean anything to him?”

“He’s in love. He’ll come round eventually. When she moves on to the next bloke he’ll see what she’s really like. She’s bound to leave him sooner or later.”

Francesca said quietly, “What if she drops him the way she dropped Misha?”

“Carlotta would take him back, you know she would.”

Francesca seemed close to tears. “He’d be wrecked. Oh Marco, if he really goes through with it, how will we manage without him?”

“We’ll manage, the way we always have,” soothed Marco. The toddler beside him raised its arms, asking to be picked up. He kissed the child on the head. “And Paolo here will be ready to join us before we know it, won’t you, my lad? The Bellinis will have a new star with or without Alonzo.”