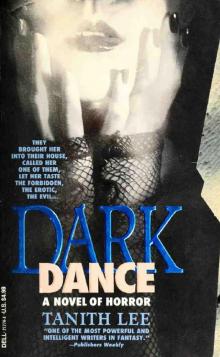

Dark Dance

Tanith Lee

Table of Contents

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

About the Author

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat: ‘we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.’

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,

Lewis Carroll

Chapter One

The woman in the fog:

It pressed round her, walls of yellow breath. She walked in a moving jail. At intervals the stem of a street light would loom like a great thin tree, or an angled wall would jut out. High above, electric windows dim as old lamplight, peering. She found her way by memory.

The fog had a sad melancholic smell that smothered everything. There was a feeling in the fog of a pursuer, but irrational, from every side.

The woman walked on. She was slim in a dark coat. Her hair was substantial, down her back, very black, like thick leaves on a bush. A slim white face and two pale eyes. One hand held her collar. She had unpainted nails, rather long.

She turned into Lizard Street, past the great building with lions, and walked into the bookshop.

‘Oh, Rachaela. You’re late.’

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘Twenty minutes.’

She walked by Mr Gerard and into the back, the tiny room with its kettle and piled newspapers, the stacks of books either shiny and plastic with newness, or old as dying brittle moths. She hung up her coat.

She wore a black skirt and dark jumper and boots. The shop was never warm except in the sweltering summer when it baked, and only the thinnest of shirts was bearable, but Mr Gerard still pottered in his sweaty jacket and tie. Today he wore the Fair Isle pullover, cheerful under his sour fat fruit of a face.

He left her his position at the counter. Trice these from my list.’

Rachaela nodded.

This job paid very little, and she was required also to make tea, fetch sandwiches, sweep the floor, and dust the stacks, which she seldom did. She never argued or complained, neither did she apologize for her laxness, her constant lateness. Mr Gerard did not threaten her. She had not stolen from him, she did not answer back. When he flew into a temper at something she stared into far distances, and afterwards seemed to forget. She was as polite as a statue to the customers, of whom there were few. Mr Gerard knew next to nothing about her. A mystery woman.

As Mr Gerard edged away into the back of his dingy, frowsty cave, a man came in to collect a book. The fog swirled vaguely through with him to fill the space, wreathing a thousand volumes.

‘Rotten day,’ said the man. ‘I thought we were finished with these things years ago. Bloody weather.’

Rachaela put his book into a bag and rang up its price on the till. The till was one of the reasons she had applied for the job a year ago. She hated computers, they frightened her. She liked old things. She was not so uncomfortable in this shop.

The customer took his book and handed her the money. Rachaela counted his change slowly, before giving it to him. Figures also bothered her. She was happy only with printed words.

‘Excuse me,’ said the customer. Rachaela looked at him, seeming shocked. Had she made a mistake with the money? ‘You’re Miss Day, aren’t you?’

She hesitated.

As if admitting a dangerous secret she said, ‘Yes.’

Her voice was low, soft and occlusive.

‘I thought so. Said I’d bring you this.’

He handed her a buff envelope. Like a spy she took it. She asked him nothing, but her slender, long-nailed hand was reluctant to carry the envelope back to her body, her hand lingered in the air between them.

‘Better explain,’ he said. He was friendly. ‘I’m from next door. Lane and Soames. The boss man asked me to bring it down to you. They’ve been looking for you, you see.’

She spoke. ‘Who?’

‘My firm, Lane and Soames. Looking, and here you were all the time.’

She had been hunted, then.

Rachaela brought the envelope into her breast. Her hands were tight upon it.

She had felt a pursuer, silent in the fog.

Day was not her name, but she had used it for years. She supposed it was legal by now; certainly it was the name on her insurance card, and by which she paid her bills.

Perhaps, however, there was a mistake.

‘Are you sure I’m the right person?’

‘Don’t ask me. I’m just the errand boy. Said I’d drop it in to you.’

His jolly eyes were vacuous, he did not like her, her distance, or her beauty, which had a noiseless closed quality, almost to be missed, not exaggerated by bright make-up or dress.

‘OK then,’ he said. ‘Out into the soup.’

He went at once and the door shut and the fog swirled. It was thick in the shop now, and Rachaela remembered Alice Through the Looking-glass, the shop with the sheep and the water swirling up...

In the back, Mr Gerard was talking on the telephone. ‘But I said to him, Mac, old dear, you just can’t—’ He would be engaged for an hour.

Beyond the windows was that soft, grey-yellow pastelled wall. Behind it might stand anything, the soldiers of an execution, starving beasts escaped from the zoo. Had it been a leopard which had followed her through the fog?

Rachaela saw that her wrists were shaking.

She tore open the letter.

‘Dear Miss Day.’

They don’t know.

‘Would you be so good as to call in at my office, at your convenience.’

Someone, someone knows.

‘My clients, the Simon family, have asked me to locate you on a matter that may prove mutually beneficial.’

That name isn’t real either.

Unless—something else—

What else could it be?

The easy answer was to ignore the solicitor’s letter. But then again, they had come so near.

Lane and Soames, a few yards away through the wall.

Rachaela saw in memory her mother’s tired and embittered face. ‘Have nothing to do with them.’

She could hear her heart. A drum in the fog.

‘Oh come on, come on!’ roared Mr Gerard to the phone far off over the hills.

At six o’clock Rachaela went out into the street. Mr Gerard locked the shop in a flurry of ancient duffel coat and scarf.

‘Filthy night.’

It was growing dark, the fog shadowing, and many bright lights shining through it, smeared and dangerous.

‘You mind how you go, Rachaela.’

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘good night.’

‘Probably you just dissolve,’ Mr Gerard said audibly and angrily to the stiff lock.

Rachaela crossed over from Lane and Soames. The great lions crouched wetly black, but did not spring. No one could make her enter between their paws.

She walked east and came among the vast animal of the evening crowd, bumping and pushing along. At a bus-stop she waited, silent, as people swore and raved at the bus’s delay. ‘You don’t live in the real world with the rest of us.’ It had

been a blinding accusation. Her mother had furiously believed Rachaela was not hurt by the world.

The bus came.

Men and women thrust in front of her. She let them. The world to Rachaela was mostly horrible and she expected nothing good of it. For this reason she had refused friendships and lovers, although once she had been raped by an acquaintance after a dull party. She only expected onslaughts, upon her privacy, her person. The rape had not shocked Rachaela. She sloughed it.

After half an hour she got off the bus, and stepped back into the belly of the fog. She had now to walk across the wide green in front of the flats. She knew its perils, she did not fear those, they were facts. It was something else she feared.

The fog brought it. It had brought the letter, too. Sitting in the snack bar at lunch time she had thought of absenting herself this afternoon from the shop. But so far she had never done that, not even when she had caught flu, and foolishly she did not want to spoil her record. She was saving her truancy for some perfect day when she would abscond to picturesque gardens or to see a film.

Besides, the letter would have been left for her. She could not have escaped.

Trees passed her, swathed and dripping.

A lit streetlight shone ahead like a living livid moon.

A man stood before her. He was suddenly there. He was very tall, dark, held in a void, faceless.

Rachaela started and her entire body went to water. Then the man was gone. There was only another tree.

‘Pardon me,’ said a voice. He was by her side, short, in a black overcoat and a woollen hat. She thought he would beg money, but instead he said to her: ‘Mr Simon is very anxious that you call at Lane and Soames.’

‘Who are you?’ said Rachaela.

‘A friend of Mr Simon’s.’

‘Leave me alone.’

‘But you must go, you know.’

It was usual to be obedient to authority, to obey a legal letter. But Rachaela left her bills unpaid until the threats began. She ignored the money-envelopes stuck through the door for starving children and the sick.

‘Go away.’

She did not run. The green ended at a pavement and the lamp filled the fog with an impenetrable vortex of light.

The dark man stared at her. He had a foreign face and gelid eyes. Would he attempt violence?

‘You go,’ he said, ‘to Mr Soames.’

And then he turned and slid into the fog.

Rachaela crossed the road and a boy cycled suddenly by like an apparition.

She climbed the steps and unlocked the door.

The fog smurred into the bleak hall, over its stone floor and the dusty table with letters. She feared to see a second letter lying there, but there was only a telephone bill, not in itself to be dreaded, for she never phoned anyone, the phone had come with the flat or she would not have bothered with it.

Rachaela took her bill and let herself into a tiny space crowded by stairs.

A year ago she had had a cat, a black round cat which was too lazy to come to greet her. But the cat was old and had died in her sleep. So Rachaela had found her one morning on her bed. Rachaela had wept for loneliness, but so far the ghost of this first cat, which she sometimes glimpsed about the rooms, had precluded obtaining another.

Nothing therefore awaited Rachaela but the usual walls, cream-washed by the landlord, and a floor carpeted by him in a faint beige.

Rachaela’s great bookcase, crammed and crowded by books, many of which now stood and leaned along the wall, did not remind her of the shop. Yet it was her connection to books which had suggested that form of employment. Before the bookshop she had done many flimsy things, served tables in a café and counters in a fabric shop, other things like these.

It was cold. Rachaela turned on the electric fire, a fixture also supplied by the landlord, ugly but warming. She drew the beige curtains against the curtain of the fog. Even this room was touched by it, it had seeped in like pollen or gas through a hundred camouflaged cracks of the house.

In her kitchen area Rachaela opened the fridge. She drew out bread and left it ready to be toasted. She made herself a mug of coffee that she did not really want, but which pleased her as it represented the home-coming ritual.

It was good seldom to worry about a meal. While her mother had lived there had always been a dinner, cheap sausages and black cabbage, watery omelettes, often burnt, and jacket potatoes with prickly eyes glaring out of them.

Rachaela’s mother had died abruptly of a heart attack. Rachaela bore the sympathy of neighbours and her mother’s friends. She was twenty-five then, and had always lived with her mother and was expected to grieve and fall in little pieces.

But Rachaela went about the bewildering process of clearing up her mother’s death without tears. At the cemetery when the joyous young clergyman had promised remembrance of the ‘dear old lad/—who had liked to think of herself, when alive, no more than middle-aged—Rachaela had known a terrible ache in all her muscles, not the least the muscle of her heart. It was her body relaxing for the first time in fifteen years. She was free.

She never ceased to be thankful for her freedom. Her aloneness was her pleasure. She missed her cat, who had given her an uncloying and nearly careless love, her cat who never raged or shouted, never told her things, never demanded. But her mother had been a weight of iron. Rachaela had stayed light as air.

Until now.

Because now it was as if her mother reached out for her again. The doom-laden asides of family history, the portion of the unknown father who had revealed just enough before deserting to leave a lifelong stigma of the cheat or the fraud.

His family, not Simon, but having a name Rachaela could hardly forget, its oddness lost in repetition, ‘Scarabae’—Scarraby it was pronounced. A weird name to go with a weird fly-by-night man. ‘I loved him, the swine, the sod,’ had said Rachaela’s mother. She had not taken his name. Her own name was Smith, so foolish that Rachaela, left alone, discarded it.

Rachaela put on the radio, the third station, and heard Shostakovich in an unmistakable clash of silver chords.

She sat by the fire and edged off her boots.

In half an hour she would make her supper, toast and cheese. Tomorrow was Friday and she would fetch a salad and some cold meat from the deli. Perhaps a glass of wine.

Outside the silence of the fog waited.

She had screwed up the letter from Lane and Soames and thrown it in the waste bin at the shop.

Perhaps she had come into some money.

Would she want it if it depended on her father’s infamous side?

‘He’s dead by now. Have to be, the way he carried on,’ her mother said loudly in Rachaela’s mind.

Four years since the funeral.

‘You never came through, did you?’ the young man said, accusatory.

She had been trying to avoid him by dusting the stacks, taking out old books that were slightly foxed, and brushing them gently.

‘Is it any of your business?’

The young man became flustered. People relied on you not to be rude to them while they tried closer and closer forms of insolence. Rachaela did not play this game.

‘No—well, yes. I delivered the letter. Now old Soames thinks I pissed about and never gave it you.’

‘But you did.’

‘Yes, I bloody well did. Why didn’t you go?’

‘Excuse me,’ said Rachaela, and slipped away around the shelves.

‘What’s all this now?’ inquired Mr Gerard, who had come from the back eating biscuits. ‘Something wrong?’

‘Er no, this young lady—I brought her over a letter from Lane and Soames and she hasn’t taken it up, and old Soames thinks I’m to blame.’

‘What letter’s this?’

Rachaela did not answer. She dusted a copy of The Egyptian and put it carefully back into its slot.

‘Something to do with property,’ said the young man. ‘That’s my guess anyway. They’re all of a doodah ove

r it, damn nuisance.’

The fog was in the shop again. Unrelentingly it mouthed the capital.

‘She doesn’t have to make an appointment. Just pop up and Soames’ll see her. Wouldn’t take a minute—’

‘You could go in your lunch hour, Rachaela. My God, don’t you think you should? It might be worthwhile.’

Rachaela did not speak.

She did not tell Mr Gerard to mind his own business since she had never been rude to him. He paid her small wages.

The young man sighed. ‘I’ll just take the biography, then. Waste of time, reading fiction.’

‘Luckily not everyone thinks so,’ said Mr Gerard with dislike. Suddenly unpopular, the young man hastened from the shop.

‘What the hell are you doing, Rachaela?’

‘I’m dusting.’

‘You never dust. Stop it. There’s clouds of muck going up. Go to lunch. Take an extra ten minutes. Go and see this Soames.’

It was Saturday morning and the animal of the crowd was out shopping. Its mood was the familiar one, surly and desperate.

Rachaela walked towards the snack bar. A man charging by slammed into her shoulder and almost spun her round. She found the man from out of the fog by her shoulder.

‘Miss Day, you will allow me to accompany you.’

He took her elbow and turned her all the way about. They moved against the crowd, which seethed and spat in their faces.

‘You’re forcing me to go there?’

‘No, no, Miss Day. You will be pleased. Come along.’

It was Saturday. Would Soames be in his office? Apparently he was.

Three youths in football colours of some team from Mars collided with them. They were no longer a unit, the foreign man and Rachaela. They were hammered apart.

Rachaela whirled into the fog, into the thick of the crowd, giving herself to its hasty rhythm.

The man did not call out after her. His hand did not clutch and grasp her arm.

She made towards the museum, where she spent her lunch hour among the blue and pink stone of god birds and smiling pharoahs, eventually eating two bananas bought from a stall as she walked to the shop, fog-bananas.

The man did not come into the shop, and the young one did not come back.