The Letters of Sylvia Plath Vol 2

Sylvia Plath

Contents

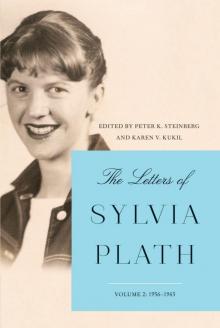

Cover

Title Page

List of Illustrations

Foreword by Frieda Hughes

Preface

Introduction

Chronology

Abbreviations and Symbols

The Letters

1956

1957

1958

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963

Acknowledgements

Index

Photo Section

About the Author and Editors

Also by Sylvia Plath

Copyright

About the Publisher

Illustrations

1.Sylvia Plath on foredeck of Queen Elizabeth. c. 25 June 1957.

2.Sylvia Plath’s pocket calendar, 21–24 November 1956.

3.Drawing of Winthrop, Massachusetts, from Sylvia Plath to Edith and William Hughes, 17 January 1959.

4.Glascock Poetry contestants and judges, c. 18 April 1959.

5–7.Photos from Plath and Hughes’s album of their 1959 cross-country trip. 5: Ready to start on the trip; 6: Encampment at Rock Lake; 7: Feeding deer.

8.Sylvia Plath at the Grand Canyon, c. 4–5 August 1959.

9.Sylvia Plath passport photograph, c. September 1959.

10.Drawing of Lupercal dust jacket, from Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 16 January 1960.

11.Drawing of 3 Chalcot Square flat, from Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 24 January 1960.

12.Edith Hughes, Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, and Frieda Hughes, 5 June 1960.

13.Sylvia Plath and Frieda, c. June 1960.

14.Sylvia Plath’s submissions list, 9 July 1960–12 April 1961.

15.Sylvia Plath atop Primrose Hill, c. 16 June 1960.

16.Drawing of sailcloth top, from Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 27 August 1960.

17.Sylvia Plath and Frieda Hughes in 3 Chalcot Square, c. 23 September 1960.

18.Drawing of a child’s dress, from Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 6 November 1960.

19.The Bell Jar, second draft of Chapter 1, c. April–July 1961.

20.Sylvia Plath and Frieda, January 1961.

21.Frieda Hughes’ first birthday, 1 April 1961. Enclosed with letter to Ann Davidow-Goodman, 27 April 1961.

22.Sylvia Plath, Frieda, and Nicholas, Court Green, late April 1962.

23.Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, Frieda Hughes, and Vicky Farrar at Court Green, Easter 1962.

24.Redactions and annotations by Aurelia Plath on page 2 of Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 23 September 1962.

25.Sylvia Plath’s Letts Royal Office Tablet Diary, 21–27 October 1962.

26.Redactions and annotations by Aurelia Plath on page 1 of Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 22 November 1962.

27.Redactions and annotations by Aurelia Plath on page 2 of Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 22 November 1962.

28.Sylvia Plath’s Letts Royal Office Tablet Diary, 16–22 December 1962.

29.Sylvia Plath with Nicholas Hughes, Court Green.

30.Vandalism (removal of SP’s signature) from Sylvia Plath to Aurelia Plath, 4 February 1963.

31.Sylvia Plath to Ruth Beuscher, 4 February 1963, Page 1.

32.Sylvia Plath to Ruth Beuscher, 4 February 1963, Page 2.

All letters and drawings by SP are © the Estate of Sylvia Plath.

Items 1, 6, 7, 8, 15, 22 are reproduced by courtesy of the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University, © Estate of Ted Hughes.

Items 2, 10, 11, 16, 18, 24, 26, 27, 30 are reproduced by courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University at Bloomington.

Item 3 is reproduced by courtesy of Frieda Hughes.

Item 4 is reproduced by courtesy of Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections; photograph by Vincent S. D’Addario, © Mount Holyoke College.

Items 5, 9, 12, 23 are reproduced by courtesy of the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University; item 5 © Estate of Aurelia Schober Plath, item 9 © unknown, items 12 and 23 © Estate of Hilda Farrar.

Items 13, 20 are reproduced by courtesy of the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections, © Estate of Ted Hughes.

Items 14, 19, 21, 25, 28, 31, 32 are reproduced by courtesy of the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

Item 17 is reproduced by courtesy of Marcia Momtchiloff, © Marcia Momtchiloff.

Item 29 is reproduced by courtesy of Sue Booth and the Lilly Library, Indiana University at Bloomington, © Sue Booth.

Foreword

This second volume of letters continues my mother’s documentation of her life and captures a flavour of her many friendships and relationships – including her relationship with my father through fourteen letters to her psychiatrist, Dr Ruth Beuscher, letters that I never thought would be included in this book. It is these letters I want to write about.

Until the end of 2016 I didn’t know these letters existed, so their inclusion wasn’t in question. And when I did find out about them, it transpired that, in my foreseeable future, their content might not be made available to me. It seemed it could be years – if ever – before I knew what revelations they might contain.

There was something deeply saddening about this; I felt excluded from my own mother’s personal feelings, feelings that other people – strangers – had already pored over. And the lack of any information about the content of those letters persuaded me to fear the worst; I imagined the terrors and anguish my mother could well have expressed in those letters in a bloody sort of way – heightened emotions and tortured thoughts all spilling out to a woman who was, to all intents and purposes, supposed to be a locked box, a professional confidante, and the trusted recipient of my mother’s self-exposure at a time in her life when her world as she knew it was disintegrating. In truth, neither I nor anyone else should ever have known those letters between a patient and her psychiatrist existed. Perhaps to preserve the doctor–patient dynamic, my mother always addressed Ruth Beuscher as Dr Beuscher, but had my mother’s suicide and subsequent fame somehow made patient confidentiality irrelevant?

Then, to my dismay, some of the contents of those letters were part-exposed on the international stage of the internet when they were put up for sale by a book dealer in the USA in March 2017. The dealer was acting for a client who’d had the letters in their possession for several years. The client had once worked on an unrealised biography of my mother in the 1970s and had communicated with Dr Beuscher. Beuscher had allowed the biographer to see, read and touch those letters as I could not – I imagine to better access the reality of my mother at her most vulnerable.

In preparing to sell the letters, the dealer pasted photographs of them on his website and large parts were clearly legible, irrespective of the law of copyright, and with no regard to the sensitive nature of the content – least of all the fact that the letters were between a client and her psychiatrist.

And so began a sort of rollercoaster hell; newspaper articles appeared about the letters, and quotes were bandied about, but only the most contentious, heart-rending quotes would do. One newspaper emailed me questions out of the blue – questions I couldn’t possibly answer – based on the quotes below, which I’d never seen until then:

22 September 1962: ‘Ted beat me up physically a couple of days before my miscarriage: the baby I lost was due to be born on his birthday.’

9 October 1962: Plath wrote that Hughes ‘seems to want to kill me’.

21 October 1962: Plath claimed that Hughes ‘told me openly he wished me dead’.

4 February 1963: ‘What appals me is the return of my

madness, my paralysis, my fear.’

In my mind, the letters were written by my distraught mother in the throes of real emotional pain; her side of the argument was the only side, and that was the side that everyone was sure to take. There would be no balancing argument; the quote that rendered my father a wife-beater had already been seized upon. He might be no angel, but where was the perspective? What else was said? Having no idea what was in those letters, other people were now writing my worst fears into them. Loving both my parents I was – I am – acutely aware of their humanity and fallibility, but these elements could be easily disregarded by others who had their own ideas and wanted to shape their own arguments.

The posting on the book dealer’s website was suddenly taken down, whether for copyright reasons or not I didn’t know, and, although I was grateful for the respite, much had escaped that caused me grief, albeit not enough to make sense of, so I dreaded the rest.

The months passed and Smith College, my mother’s college, eventually came into possession of the letters. They contacted me to discuss how students and academics might access them – at this point, publication was as far from my mind as Saturn. Conscious that the material was supposed to have been confidential in the first place, I asked to read them before we discussed this, and was sent scans: at last, my fears were going to be addressed.

It was a Sunday morning when I took the letters to bed to work my way through them – it seemed a more comforting environment; at this point, before transcription, I was struggling to read enlargements of the scans, having darkened the type on the photocopier in an attempt to make the words more legible – the letters were faded and worn with age.

I simply wept over the contents.

Those fourteen letters were snapshots of my parents’ passionate relationship and subsequent marriage; the finding of a city home, the birth of children, their move to the country and the adoption of what would be an unsustainable idyll, followed by my mother’s suspicion of my father’s affair, the confirmation of that suspicion, her decision to separate, the strengthening of that resolution, the apparent realisation that they had been living in what I think of as a hermetically sealed bubble in which they ran out of oxygen, then the decision (following Ruth Beuscher’s written advice) that divorce was the best option, and finally, the letter I feared most, the letter in which my mother’s madness returns just before she kills herself.

My journey began with the first of the letters, dated 18 February 1960, almost exactly three years before my mother died. In it, she describes how she and my father found their new home, the tiny flat at 3 Chalcot Square, Primrose Hill, in London. She was pregnant with me, had just received an acceptance from Heinemann for her first book of poems, The Colossus, and was overjoyed to be in London: ‘I can’t think of anywhere else in the world I’d rather live . . .’

This letter, I thought with some relief, was wonderfully positive and full of hope. It was followed by one written on 2 April, announcing my home birth the day before in the kind of detail no child really wants to know from a parent; my mother had written about everything from the Indian midwife on a bicycle, to the length of her contractions, the details of dilation, and my appearance upon arrival. The publication of my father’s book Lupercal, and my mother’s book The Colossus, were also almost upon them – additional births.

The picture of my parents in my mind solidified; it was mutually supportive and intensely close, they were working together for common goals and I could see the hulk of my father writing away in the ‘windowless hall’, my mother holding me as she slipped him cups of tea. I’ve visited the flat in Chalcot Square only once, when an English Heritage Blue Plaque was put on it in 2000 and my late brother, Nicholas, and I unveiled it together: it is so tiny that when I stepped into the hallway it was one pace past the bathroom, two paces into the kitchen, turn right and one pace into the tiny living room, one pace across the living room, turn right and one pace into the bedroom, which was so small it wasn’t possible to swing a gerbil. I changed my clothes for the unveiling in the bedroom I was born in.

In the third letter, dated 7 November 1960, describing scenes of domesticity and industry, my mother explained how they were together so much that it was good they now had to explore London separately, my father being ‘an angel about my excursions, feeds Frieda lunch and so on’. So far, so good, I thought, dreading the impending dissolution of my family as I continued to read . . .

The fourth letter was misdated as 4 January 1960, when it should read ‘4 January 1961’: I am still a baby. It concerns ‘an old and ugly problem . . . namely Ted’s sister’. In this long letter my mother describes my Aunt Olwyn’s behaviour towards her over Christmas in 1960 – behaviour that can only be described as abusive. She writes: ‘my presence is intolerable to her’ and correctly surmises that Olwyn disliked all the ‘other’ women in my father’s life, being irrationally possessive of him. So I had not been the only recipient of my aunt’s excoriating remarks and furious verbal attacks over the years; my mother had suffered them too. It was strangely comforting reading my own experiences through my mother’s words; her description of my aunt was disturbingly familiar to me.

In the fifth letter dated 27 March 1962 she writes about the discovery of the house in which my brother was born on 17 January earlier that year, and where he and I were (mainly) to live until we finally left home – Court Green in North Tawton, Devon. The rooms were ‘huge’ my mother wrote, then going on to describe my brother’s character: while I was ‘lively, hectic, & a comic’ he was ‘dark, quiet, smily’, and there was a ‘very nice ruddy Devon woman in 3 mornings a week . . . to do all the work I hate---ironing, floor-scrubbing’. Life was full of promise, it seemed, and all my parents had to do was survive what some would find a stifling proximity as they both lived and worked at home, now with two babies.

In this letter there is also the mention of her miscarriage: ‘I had lost the baby that was supposed to be born on Ted’s birthday this summer at 4 months, which would have been more traumatic than it was if I hadn’t had Frieda to console and reassure me. No apparent reason to miscarry, but I had my appendix out 3 weeks after, so tend to relate the two.’ I was hugely relieved; there was no mention of ill-treatment by my father as quoted in the newspapers, only an appendectomy . . . surely my mother would have mentioned something to Beuscher at this point if my father had been abusive?

But by the sixth letter, dated 11 July 1962, the cracks were beginning to show; my mother had noticed a change in my father’s behaviour, as if he had found a new lease of life sparked by people and situations she did not know about and could only guess at: the woman who took over the lease on Chalcot Square kept phoning my father ‘seeming almost speechless when she got me’. Now there was anguish, paranoia and suspicion. My mother frantically analysed the permutations of my father’s apparent new interest, fearing that, if he left her, she would not find another like him. Her own mother was staying for six weeks, and my father was away in London; how would she keep up the appearance that all was well? She was, however, certain that she didn’t want a divorce: she would like to ‘kill this bloody girl to whom my misery is just sauce’.

By the seventh letter, dated 20 July 1962 my mother is begging Beuscher to charge her some money: she is, after all, a client writing to her therapist. She is also, it seems, feeling more open-minded and less reactionary: ‘I remember you almost made me hysterical when you asked me, or suggested, that Ted might want to go off on his own . . . How could a true-love ever want to leave his truly-beloved for one second? We would experience Everything together.’ It is hard to imagine that anyone looking into my parents’ relationship from the outside wouldn’t think it so claustrophobic that something must give, if they didn’t each develop a life outside the marriage.

She admits: ‘I think obviously both of us must have been pretty weird to live as we have done for so long.’ Her feelings towards her father, Otto Plath, she confessed, would further complicate their relationshi

p – as, she surmised, would my father’s feelings for his mother and sister. She called my father’s love-interest, Assia Wevill, ‘this Weavy Asshole’; flashes of defiance and imaginings of what might be going on in Wevill’s head fill the pages. My father was drifting away, he no longer did ‘any man’s work about the place’. My mother wrote too, about sex; in a plain, matter-offact kind of way I was given a brief history of her sexual education. She sounded stronger too: ‘I don’t think I’m a suicidal type any more . . .’ I could only wish that had been the truth.

In her eighth letter, written on 30 July 1962, my mother’s possessiveness over my father drove her to write: ‘What can I do to stop him seeing me as a puritanical warden?’. She compared him to the hawk in his favourite poem that kills where it pleases and wrote: ‘I realise now he considered I might kill myself over this . . . and what he did was worth it to him.’ I consoled myself that these were her words in elaboration of some other truth, not his, because as we work ourselves out through adversity we conjecture and suppose and imagine and can drive ourselves into the floorboards like a nail in this way. She added: ‘And he does genuinely love us. He says now he dimly thought this would either kill me or make me, and I think it might make me. And him too.’ Being broken apart, it seemed, might create as much energy and art-flow as getting together had – after all, it was all born of their heightened emotional states.

By letter nine, dated 4 September 1962, and suffering what seems to be never-ending influenza, my mother was more resolute about a separation; she was impatient, angry at her illness, and determined to forge ahead despite my father’s prospective absence from her life.

Her dependence on advice from Dr Beuscher is emphasised in the tenth letter, dated 22 September 1962: ‘I am really asking your help as a woman, the wisest woman emotionally and intellectually, that I know.’ A childhood memory is the basis of my belief that my mother asked my father to leave, but in her letter to Beuscher she wrote: ‘Ted “got courage” and left me.’

Undoubtedly, my father would have made it easy for my mother to ask him to leave, through his behaviour, his affair, and his deceit. Then here was my mother, writing how for weeks she had been on a liquid diet, apparently highly strung, volatile, paranoid and accusatory; was it a result of the disintegrating marriage? A sick person can rule through their sickness as, in one letter, my mother believed my father imagined she was doing. They were two people negotiating the difficulties of what had become a stifling partnership in which feelings of ownership appeared to be a contributory factor, certainly on my mother’s side. My father may have reacted to a perceived lack of freedom and had his affair, but culpability lay with both of them. There was nothing new or groundbreaking in this; it was simply a case of two people having lived so closely that they imploded, tearing one another apart in the emotionally messy way that thousands of other couples do.