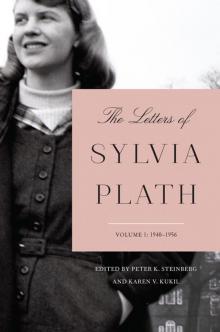

The Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume 1

Sylvia Plath

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

List of Illustrations

Foreword by Frieda Hughes

Preface

Introduction

Chronology

Abbreviations and Symbols

THE LETTERS

Photo Inserts

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Authors

By Sylvia Plath

Copyright

About the Publisher

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Sylvia Plath, Ruth Freeman and David Freeman, Winthrop, Massachusetts, 1938.

2. Self-portrait of SP holding a flower next to her Aunt Dorothy holding a wand, from SP to Aurelia Schober Plath, 20 February 1940.

3. Sylvia Plath and campers at ‘Trading Post’, Camp Weetamoe, Center Ossipee, New Hampshire, July 1943.

4. Margot Loungway in Maine, 1 November 1944.

5. Drawing of a winter scene with moon, from SP to Frank Schober, 16 January 1946.

6. Drawings of a painted frame, of a bicycle, and of girl holding a piece of paper sitting at a desk with an inkwell on it, from SP to Marion Freeman, 16 April 1946.

7. Drawing of a peach on a leafed branch, from SP to Marion Freeman, 4 November 1946.

8. Drawing of a sailboat with ‘SYLVIA FOR SECRETARY’ written on the sail and port side, from SP to Margot Loungway, 11 January 1947.

9. Drawing of the beach, houses, and the ocean, from SP to Aurelia Plath, 5 July 1947.

10. Drawing of a ‘freak’ girl scout, from SP to Aurelia Plath, 20 July 1948.

11. Sylvia Plath, c. 1950.

12. Drawing of a horse’s head, from SP to Ann Davidow-Goodman, c. 12 January 1951.

13. Drawing of SP with a sprained ankle, from SP to Ann Davidow-Goodman, 9 May 1951.

14. Drawings of four pieces of clothing, from SP to Aurelia Plath, 6 May 1951.

15. Drawing of SP mowing the lawn, from SP to Marcia B. Stern, 6 June 1951.

16. Drawing of Joanne, Esther (Pinny), and Frederic Mayo, from SP to Ann Davidow-Goodman, 26 June 1951.

17. Self-portrait holding a book, from SP to Marcia B. Stern, 1 July 1951.

18. Sylvia Plath standing beside a bicycle, Marblehead, Massachusetts, 24 July 1951.

19. Drawing of a female on crutches in a high wind with hands reaching through ice, from SP to Myron Lotz, 9 January 1953.

20. Drawings of jackets, dresses, and a shoe, from SP to Aurelia Plath, 28 April 1953.

21. Drawing of a female wearing a robe, on a pillow, holding a pen, from SP to Gordon Lameyer, 22 June 1954.

22. Drawing of streets, houses, and ocean in Winthrop, Massachusetts, from SP to Gordon Lameyer, 22 June 1954.

23. Drawing of soup on a table, from SP to Gordon Lameyer, 22 June 1954.

24. Sylvia Plath at Chatham, Massachusetts, c. 24 July 1954.

25. Sylvia Plath and Ruth (Freeman) Geissler on Ruth’s wedding day, Winthrop, Massachusetts, 11 June 1955.

26. Drawing of SP’s room at Whitstead, from SP to Aurelia Plath, 2 October 1955.

27. Drawing of a coffee table with a plant, a New Yorker, and other items on back of an envelope, from SP to J. Mallory Wober, 16 November 1955.

28. Drawing of a female figure in dressing room looking in mirror holding a pen, from SP to J. Mallory Wober, 24 November 1955.

29. Drawing of a bouquet of daffodils on back of an envelope, from SP to Aurelia Schober, 2 February 1956.

30. Sylvia Plath atop Torre dell’Orologio, Venice, 8 April 1956.

31. Sylvia Plath at Fontana Muta, Rampa Caffarelli, Rome, 10 April 1956.

32. Sylvia Plath sitting on stone wall with typewriter, on Yorkshire moors, September 1956.

All letters and drawings by SP are © the Estate of Sylvia Plath.

Items 1, 11, and 25 are reproduced by courtesy of Ruth Prescott Geissler, © Ruth Prescott Geissler.

Items 2, 6, 7, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 32 are reproduced by courtesy of the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College. No. 18 © Estate of Marcia B. Stern; No. 32 © Elinor Klein.

Items 3, 5, 9, 10, 14, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 31 are reproduced by courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. No. 3 © Unknown; Nos 24, 30, 31 © Estate of Gordon Lameyer.

Items 4 and 8 are reproduced by courtesy of the Estate of Margot Loungway Drekmeier; No. 4 © Estate of Margot Loungway Drekmeier.

Items 27 and 28 are reproduced by courtesy of the King’s College Archives, Cambridge University.

FOREWORD

My mother, Sylvia Plath, wrote an enormous number of letters during her all-too-short lifetime: letters to family and friends about family and friends; about work, to promote work, to submit work; as well as writing her Journals (published by Faber, UK, and Anchor Books, US.) I am in awe of her output, and the way in which she recorded so much of her life so that it was not lost to us. Through publication of her poems, prose, diaries, and now her collected letters, my mother continues to exist; she is best explained in her own words, capturing a real sense of the era at the time, and her passion for literature and life – and for my father, Ted Hughes.

It has always been my conviction that the reason my mother should be of interest to readers at all is due to my father, because, irrespective of the way their marriage ended, he honoured my mother’s work and her memory by publishing Ariel, the collection of poems that launched her into the public consciousness, after her death. He, perhaps more than anyone, recognised and acknowledged her talent as extraordinary. Without Ariel, my mother’s literary genius might have gone unremarked forever. Although, by ensuring her work got the attention it surely deserved, my father also initiated the castigation that was to hound him for the rest of his life.

It seems to me that, as a result of their profound belief in each other’s literary abilities, my parents are as married in death as they once were in life.

Frieda Hughes

2017

PREFACE

This complete and unabridged edition of Sylvia Plath’s letters, prepared in two volumes, finally allows the author to fully narrate her own autobiography through correspondence with a combination of family, friends and professional contacts. Plath’s epistolary style is as vivid, powerful, and complex as her poetry, prose and journal writing. While her journal entries were frequently exercises in composition, her letters often dig out the caves behind each character and situation in her life. Plath kept the interests of her addressees in mind as she crafted her letters. As a result, her voice is as varied as the more than 1,390 letters in these volumes to her more than 140 correspondents.

Plath’s first letters to her parents were written in pencil in a cursive script. She often illustrated her early letters with drawings and flourishes in colour. Later letters were either written in black ink or typed on a variety of coloured papers, greeting cards and memorandum sheets.

Most of the original letters are held by the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, and the William Allan Neilson Library, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. Additional letters are dispersed among more than forty libraries and archives. Some letters are still in private collections.

Sylvia Plath was extremely well read and curious about all aspects of culture in the mid-twentieth century. As a result, the topics of her letters were wide-ranging, from the atomic bomb to W. B. Yeats. All phases of her development are documented in her correspondence. The most intimate details of her daily life were candidly described in letters to her mother from 1940 to 1963. (This correspondence, originally published in an abridged form by Aurelia Schober Plath as Letters Home, appears here in a complete trans

cription for the first time.) Plath wrote about early hobbies, such as stamp collecting, to one of her childhood friends, Margot Loungway Drekmeier. During high school, she explained the intricacies of American popular culture to a German pen pal, Hans-Joachim Neupert. There were many men in Plath’s life. To an early boyfriend, Philip McCurdy, she wrote about friendship as their romance waned. Later to some of her former Smith College roommates, such as Marcia Brown Plumer Stern, she wrote about her travels in Europe, marital relationships, motherhood, and domestic crafts. In the sixteen letters written to Ted Hughes shortly after their marriage and honeymoon, Plath described her courses and life in Cambridge. Her discussion of their poetry documents their extraordinary creative partnership. Plath’s business-related letters show a different side. Readers familiar with her journals will know she long sought publication in the New Yorker. Plath’s correspondence with several editors of the New Yorker demonstrates her efforts to satisfy concerns they had about lines, imagery, punctuation, and titles. Her submissions were not always accepted, but what arises is a healthy working relationship that routinely brought her poetry to publication. In addition to her literary development, the genesis of many poems, short stories, and novels is fully revealed in her letters. Her primary focus was always on her poetry, thrusting up from her ‘psychic ground root’.

Some memorable incidents from Plath’s life were recounted and enhanced multiple times in her letters and often found their way into her prose and poetry. She was so conscious of her audience that even when her experiences were repeated there were subtle variations of emphasis aimed to achieve a maximum response or reaction.

When Plath’s Letters Home was published in the United States in 1975 (and in the United Kingdom the following year), the edition was highly selected with unmarked editorial omissions, changes to Plath’s words, and incorrect dates assigned to some letters. Only 383 of 856 letters to her mother and family were partially published in Letters Home. By contrast, the goal of this edition of Plath’s letters is to present a complete and historically accurate text of all the known, existing letters to a full range of her correspondents. The transcriptions of the letters are as faithful to the author’s originals as possible. Plath’s final revisions are preserved and her substantive deletions and corrections are discussed in the footnotes. Plath’s spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and grammar, as well as her errors, have been carefully transcribed and are presented without editorial comment. Original layout and page breaks, however, are not duplicated. Incredibly frugal and conscientious of the limited space available to her, Plath wrote and typed to the very edges of her paper. This was especially the case when she wrote from England on blue aerogrammes. Occasionally, punctuation marks are not present in the original letters, but are implied by the start of a new sentence or paragraph. As a result, when Plath’s intention was clear, punctuation has been added to the letter without editorial comment.

Dates for undated letters were assigned from postmarks and/or internal and external evidence and are identified with a circa date (for example, to Ann Davidow-Goodman, c. Friday 12 January 1951). In some instances where dating a letter exactly proved too difficult or uncertain, we have offered either a range of days or simply the month or the year (for example, to Mademoiselle, c. February 1955 and to Edith & William Hughes, c. 1957). Locations of the original manuscripts are also included in the introductory header for each letter. Scans of selected drawings included in letters by Plath and photographs of her life are gathered together in the plates. Enclosures of early poems have been transcribed and included with the appropriate letter. Many of these photographs and poems have never been published.

Comprehensive factual and supporting footnotes are provided. These annotations aim to bring context to Plath’s life; her experiences, her publication history and that of Ted Hughes, cultural events, and her education and interests. Significant places, family, friends and professional contacts are identified at their first mention. Where possible, the footnotes supply referential information about the letters to which Plath was responding, as well as the locations for books from her personal library and papers written for her university courses. We made use of Plath’s early diaries, adult journals, scrapbooks, and personal calendars to offer additional biographical information in order to supply, for instance, dates of production for her creative writing.

An extensive index completes the publication and serves as an additional reference guide. The adult names of Plath’s female friends and acquaintances are used, but the index also includes cross references to their birth names and other married names.

As we read, edited, and annotated the letters initially available to us, we kept a running list of all the other letters Plath mentioned writing, which number more than 700. Some letters were destroyed, lost or not retained, such as those to Eddie Cohen and to boyfriends Richard Sassoon and Richard Norton. Other letters are presumed to remain in private hands, such as a postcard sent from McLean Hospital in December 1953, which was offered for sale at Sotheby’s in 1982. Plath wrote letters and notes to many other acquaintances, Smith classmates, publishers, teachers, and mentors, as well as to family friends. We attempted to contact many of these recipients; a majority of these requests went unanswered. Those who did respond yielded some positive results. After this edition of The Letters of Sylvia Plath is published, additional letters that are discovered may be gathered for subsequent publication.

INTRODUCTION

Sylvia Plath was many things to many people: daughter, niece, sister, student, journalist, poet, friend, artist, girlfriend, wife, novelist, peer, and mother; but perhaps the most overlooked feature of her life was that she was human, and therefore fallible. She misspelled words, punctuated incorrectly, lied, misquoted texts, exaggerated, was sarcastic, and sometimes brutally honest. All, and more, are aspects of the Letters of Sylvia Plath.

The first letters collected in this volume are to Sylvia Plath’s parents, written in February 1940. They were found in the attic of the Plath family home at 92 Johnson Avenue, Winthrop, Massachusetts. Plath was seven and a quarter years old and staying temporarily with her grandparents nearby at 892 Shirley Street when her correspondence begins. Written in pencil on 19 February, the letter to her father, Otto, includes a heart-shaped enclosure in which she expresses concern for his health, ‘I hope you are better’ and is signed ‘With love / from / Sylvia’. Plath’s readers may recognize the same imagery in ‘Daddy’, when the speaker claims her father had ‘bit my pretty red heart in two’. Otto Plath died later that year. On 20 February, Plath wrote to her mother, the first of more than 700 letters sent over the next twenty-three years, adding a crayon drawing to illustrate the text. Throughout her life, Sylvia Plath would express herself in the medium of drawing, as well as the literary arts, often combining the two in her correspondence.

Between 1943 and 1948, Plath spent her summers away from the family home at camps in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. She wrote nearly every day to her mother, less frequently to her brother and maternal relatives. These letters show from the start the importance afforded to correspondence in the Plath household. We may take for granted today the ease and instantaneousness of communication, but in the 1940s replies were slower. On 18 July 1943, Plath wrote ‘I didn’t get a letter from you yesterday, I hope you are all right . . . Are you well? I worry when I don’t receive letters from you.’ These letters tender a catalogue of quintessential activities from swimming and hiking to arts and crafts and eating. The young Plath had a voracious appetite as evidenced by this meal in July 1945: ‘For lunch I had a bird’s feed of 6 plates of casserole & sauce containing potatos, peas, onions, carrots, chicken (yum, yum); five cups of punch and a scoop of vanilla, coffee, and orange ice cream.’ Here, Plath’s sense of humour shines through: ‘If you’re hard up on ration points when I come home you can have Joe slaughter me and you can eat me for pork.’ In time, Plath became competent and energetic about food preparation. She hosted a large party while attending

Harvard Summer School, serving ‘a huge bouffet, with delectable varieties of meat, fish, hors d’ouvres, desserts’ (5 August 1954). She made the most of limited resources on ‘a single gas ring’ as a Fulbright student at Newnham College by managing ‘to create a steak dinner complete with sherry, hors d’oeuvres, salad, etc. in rebellion versus English cooking’ (14 December 1955).

The earlier letters also include Plath’s youthful verse and some of these poems appear here in print for the first time. In a letter dated 20 March 1943, Plath sent her mother the following quatrain:

Plant a little seedling

Mix with rain and showers,

Stir them with some sun-shine,

And up come some flowers.

The predominant themes of fairies and nature that appeared in these poems were acknowledged by Plath much later when she was asked ‘What sort of thing did you write about when you began?’ She replied:

Nature, I think: birds, bees, spring, fall, all those subjects which are absolute gifts to the person who doesn’t have any interior experience to write about. I think the coming of spring, the stars overhead, the first snowfall and so on are gifts for a child, a young poet.

In their focus upon her immediate surroundings, the poems by the young writer composed at summer camp established a practice that she continued until the end. In ‘Camp Helen Storrow’, the speaker observes ‘The trees are swaying in the wind / The night is dark & still’ (7 July 1945); likewise in Plath’s late poem ‘Mystic’, the speaker’s memories allude to her time at summer camp, ‘I remember / The dead smell of sun on wood cabins’. Plath had success writing about places. For example, her poems about Cape Cod, Massachusetts (‘Mussel Hunter at Rock Harbor’), Grantchester, England (‘Watercolour of Grantchester Meadows’), and Benidorm, Spain (‘The Net Menders’) were each accepted for publication by the New Yorker. Similarly, she regularly published travel articles in the Christian Science Monitor.

Plath’s non-familial letters begin with a friend Margot Loungway Drekmeier (seventeen letters, 1945–7); her best friend’s mother Marion Freeman (twelve letters, 1946–62); and a German pen-pal Hans-Joachim Neupert (eighteen letters, 1947–52). In these we learn of Plath’s little-known interest in philately; her sincerity and graciousness to a woman she considered a ‘second mother’; and her ability to relate to a foreign pen-pal and convey what it was like growing up in America. What readers will see here is Plath’s empathetic attention to her recipients and how, like writing a poem or short story for a specific market, she was able to craft a letter concentrating solely on her relationship to the addressee. There are often inside jokes and other content that will be above our heads, but Plath’s letter writing is a serious art form.