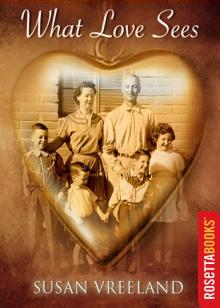

What Love Sees

Susan Vreeland

What Love Sees

A Biographical Novel

Susan Vreeland

Copyright

What Loves Sees

Copyright © 1988, 1996 by Susan Vreeland

Cover art to the electronic edition copyright © 2012 by RosettaBooks, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

“A Wedding Toast” from THE MIND-READER, © 1972 by Richard Wilbur, reprinted with permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Quotation from the poem “Love” by Mary Baker Eddy used courtesy of The Mary Baker Eddy Collection.

Electronic edition published 2012 by RosettaBooks LLC, New York.

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795323515

To

Jean Treadway Holly

Contents

A Wedding Toast

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

A Wedding Toast

St. John tells how, at Cana’s wedding feast,

The water-pots poured wine in such amount

That by his sober count

There were a hundred gallons at the least.

It made no earthly sense, unless to show

How whatsoever love elects to bless

Brims to a sweet excess

That can without depletion overflow.

Which is to say that what love sees is true;

That the world’s fullness is not made but found.

Life hungers to abound

And pour its plenty out for such as you.

Now, if your loves will lend an ear to mine,

I toast you both, good son and dear new daughter.

May you not lack for water,

And may that water smack of Cana’s wine.

Richard Wilbur

Prologue

I suppose I am in love with sound—loons, cathedral organs, opera arias, mooing cows. Even bickering children have their appeal and the lonely drip of rain from drain pipes that I hear now. It doesn’t matter whether sounds are elegant or harsh. I love them all. Sound is not denied me.

Father couldn’t understand why I shut him up during his last visit west when a killdeer trilled a holy melody right outside the kitchen window. I think he was just shocked because I told him to be quiet. I didn’t used to do that. In the years when I was really his daughter, I would no more have thought to shut him up than to stop the dawn.

I don’t remember what he looked like. I think he may have had a high forehead and square jaw, but that doesn’t tell much. His voice always told me more, that deep-throated resonance that spoke his disapproval with a grunt. Mother’s disapproval was kinder, yet I never felt I knew her as I knew Father. Eventually their faces faded into mistiness. They came to be voices only, that and the scents of pipe smoke and rose cologne. Mother taught me restraint; Father, patience.

I came home to Hickory Hill, to that enormous Georgian brick house where I grew up, to hallow the death of a parent. What I felt was not so much sorrow at Father’s death—he lived as he wished to, the manager of the tiny universe of our family—as wonder at my own life. For all your life you have a father, an inexorable tie to home and origins. And then one day he vanishes. All that you have become, because or in spite of those origins, is thrown at you and a deep voice says, “Here, take yourself. Proceed alone. You are free.” And then, piece by piece, you put his words to rest.

The house was colder than I remembered it, and footsteps echoed as they do in museums. I walked the whole house, my fingers trailing over the one grand piano left from a pair, and then the cold iron rail of the staircase, not that I needed to feel my way. I leaned out my old bedroom window to breathe the roses from the terrace below but smelled only earth sodden by November rain. I went back downstairs.

If Father had been poor, I’d have grown up faster. Since I couldn’t quite decide which of two events lurched me from childhood into adulthood—returning home from Harkness Hospital or leaving home for good—both battled for attention as I stood in Father’s wood paneled library utterly empty without his pipe smoke. Here he had taught me to be a stoic, even before I knew the word. Privately I knew how to cry, but not to scream. Too public.

Father, what color was your hair?

Chapter One

1930

“Keep your head still, Jean.”

“I am.”

That seemed to be the only sentence anybody ever said to her. They didn’t know how hard it was. With her eyes bandaged for months, there was nothing to do. Nothing to look at. The door, window, dresser, everything in that blank hospital room swam vaguely in her memory. The sandbags on both sides of her head felt hot and her back hurt from lying in bed all day.

She wished Lucy were here. Back home months before, the day her doctor told her she had to keep her head still, her younger sister Lucy read the Sunday funnies to her all afternoon until they could get her to the hospital. She even described what the characters were doing—Andy Gump, and Orphan Annie with her saucer no-eyes.

Once, years earlier, before she was old enough to read the comics, some older kid laughed at her and said, “Those stupid glasses make you look like Orphan Annie.” She had them since she was two and was afraid not to wear them. Both of her brothers wore glasses, too. Later, when she saw Orphan Annie in the comics for the first time, those round white eyes shot off the page at her and she hated Annie and turned the page to Mutt and Jeff so quickly she ripped it. But she was curious and the next Sunday she forced herself look at Annie’s eyes for a long time, until she got used to them. Almost anything was bearable if you got used to it, Mother always said, so she looked for Annie each week. She discovered Annie wasn’t scared of anything and she did exciting things, maybe because she was an orphan. Eventually, Annie became her favorite. Jean did look a little like her, she guessed, because her hair was curly too, but not red like Annie’s. Just plain brown. In bed in the hospital, she wondered what Annie did this week, but Lucy probably wasn’t going to come, so she wouldn’t know.

Most of the time Lucy didn’t visit with Mother and Father. And even they could only come from Connecticut to New York on Sundays. When they were here, she felt a little like she were back home at Hickory Hill. It wasn’t anything Mother and Father said or did when they were here. All they could do was sit in the room. Mother talked about Jean’s brothers, and Father talked about Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. It was Father’s pipe smoke that made

her feel homey. It smelled like cherries and burning leaves, and for the hour they were there, she didn’t breathe the ether of the hospital.

“Did you read the funnies this morning, Father?” she asked the last time they came, but she didn’t really think he had.

“No.”

“Nurse Williams said that last week Annie sold pencils on the street next to a man who was selling apples. Did you see any real people selling pencils?”

“Where?”

“Outside on the street. Miss Williams said it’s true—that men are selling things in the streets and people are standing in lines for soup.”

“We didn’t see any near here, but there are some.” Mother’s voice got softer. “Some people are having a hard time.”

That last visit was over so fast. Father didn’t even touch her when he said goodbye. He just said, “Keep your head still, Jean.”

How many times a day did she hear it? Even in the middle of the night she heard it. Last month for her twelfth birthday Father and Mother had brought her a chiming clock, made by the Ingraham Clock Company, the business Mother’s family owned. There was a button she could push on the left side and it would chime the hours. The button on the right side chimed the minutes. It sounded musical and the last note always echoed. Once she woke up in the middle of the night and wondered what time it was. Still lying on her back, she slithered her hand sideways out of the covers and found the left button. Three chimes sounded, but before she could find the other button, she heard, “Jean, keep your head still.” Right in the middle of the night! Sometimes she wanted just to tell everybody never to say it again, that she was trying as hard as she could.

One other sentence echoed with it in her mind every so often, but that was her own: if it doesn’t work. That sentence, she never knew how to end. Keep your head still…but if it doesn’t work. The words battered at her in a nightmare that never ended. She’d already lost sight in one eye, two years earlier, from inherited causes, Dr. Wheeler had said. This would be different. She tried not to think about it, but couldn’t help it. There was nothing else to do.

If it didn’t work, and she’d never see again, what would it be like? Would her friends still want to be with her? What about Sybil? Would they ever go out to that secret place behind the mulberry tree in Sybil’s back yard to smoke? She remembered and it made her happy, but she wasn’t even supposed to smile. It might disturb her eyes. She and Sybil used to find horse chestnuts and dig out the insides with a knife in order to stuff them with withered grape leaves. Then they’d poke a hole in the side and wedge in a thick, hollow spaghetti. If they were careful and the spaghetti didn’t break, they’d light it. It tasted terrible, but it made a lot of great smoke. It was better than smoking corn silk wrapped in The Bristol Press with her brother Bill. That just tasted like burning paper.

She could still do that even if, well, if she couldn’t do other things. And if the operation didn’t work, she could still go to dancing school. Maybe. But would Don or Bobby ask her to dance? The thought jabbed at her. What would happen when they played Truth, Dare or Consequences? Would they kiss her behind the pillow like they’d done before, both of them? She liked Bobby. Once he brought wild pink arbutus to her from the woods on the Hill—they smelled like spring—and he was the first one to write in the scrapbook her class sent her on her twelfth birthday. She remembered part of his poem:

If wishes were horses

I’d take a long ride

Down to New York

To be by your side.

That was nice. There was more of it, too, which she couldn’t remember no matter how hard she tried, and the nurses were too busy to read it to her again. Bobby seemed older than the others to write that. Well, she could still climb the apple tree with him if he dared her to.

But if it didn’t work, that is, if she couldn’t see, she wasn’t sure about climbing onto the roof. It was three stories up. She hadn’t been afraid at all before. She’d done it lots of times. It was exciting. “I dare you to touch the lightning rod,” she’d whisper to Bill at breakfast. He was a year older.

“Dares go first.”

Just what she was waiting for. They’d climb out Bill and Mort Junior’s bedroom window to the second floor terrace roof. That was gravel and flat—easy. Then they’d hoist themselves onto the steep slate part and go up higher, to the third floor dormer windows. She remembered how the soles of her feet throbbed when she sidestepped across the pointy peak of the roof out to the edge to reach the lightning rod, but that didn’t matter. She would do it anyway, usually even before Bill would. Mort was too old. It wasn’t any fun to dare him. If Father ever found out, they’d get a tongue-lashing. Now, even Bill probably wouldn’t dare her any more. She took a deep breath and let it out slowly.

She remembered how free it felt way up there, level with the top branches of the hickory trees in the woods. Hickory Hill, their house, was almost at the top of Federal Hill which everyone in the neighborhood simply called “the Hill.” From the roof she could see the grass triangle of Federal Hill Green where she went to school. She could see into the town of Bristol, to Father’s gray stone bank and the high school, but she couldn’t quite see the industrial part of town by the river or Horton Manufacturing Company, the factory Father owned. When she was up on the roof, she felt like a bird, or at least like she wanted to be a bird. Not forever, just for a while. It would be nice now, she thought. Birds could move their heads. They could go anywhere.

Except Chanteur couldn’t. Poor Chanteur was in a cage next to her, the only thing in the room that seemed real. She knew everything the canary could sing, the short little chirps that sounded like he was practicing scales. Then there were lyrical passages that reminded her of “Greensleeves.” She wondered what Chanteur looked like. Maybe she’d never see him. She had to find out. That was all, she just had to.

The hospital seemed quieter than usual. No one had walked by in the hall for a long time. If she were quiet, maybe no one would discover her moving around. She lifted the covers and slowly swung her legs out over the edge of the bed. Her heart beat so hard it made her chest and throat bounce. She slid down carefully until her toes touched the floor. It felt like cold stone. With her hands in front of her, she edged toward the bird’s song, trying to keep her head very still. The room was smaller than she remembered so her foot rammed into the table leg and shook the cage. The bird stopped singing.

“It’s okay, Chanteur,” she whispered. “I won’t hurt you.” Her hands sought the door of the wire cage and opened it. She reached inside and he started flapping around. Feathers brushed by. Probably his tail. Not very soft at all. His body would be softer. She moved her hand to the left. Wings flapped. Tiny claws scraped across the back of her hand to the right. She went right. The bird let out a screech. She drew in her breath. “I won’t hurt,” she cooed again. She kept her hand still. Maybe he would calm down and stand on her finger. Nothing happened. She closed the cage door and picked her way back to bed, her heart thumping.

“What’s all that racket?” Nurse Williams asked at the doorway. “You’ve been out of bed again, Jean Treadway, I just know it.”

“Who, me?”

“You’ve been moving your head, bothering that bird again, haven’t you?”

“No, I wouldn’t hurt him. He’s my yellow music box.”

“Yellow? That bird’s not yellow.”

“I thought all canaries were. What color is he?”

“Kind of a blue-gray.”

It wasn’t an important thing, but it shocked her. She couldn’t assume anything anymore.

Another patient, Mrs. Whitelaw-Reid, whose husband owned some big New York newspaper, gave her the canary. It didn’t occur to her then to ask what color it was, but later when Mrs. Whitelaw-Reid gave her a fluffy comforter for her birthday, she asked what that looked like. Comforters could be any color. “It has yellow flowers on a white background,” Mrs. Whitelaw-Reid said in a voice that reminded her of a clarinet.

Now Jean wondered whether this lady looked as soft as she sounded. Or maybe she was big and mean-looking and only sounded sweet. How was she to be sure of anything?

A few weeks earlier, after Jean’s second operation, Mrs. Whitelaw-Reid bought her a typewriter. It was such a big gift she didn’t know how to respond. What did Mrs. Whitelaw-Reid know that would make her give her a typewriter? It made a hollow feeling in her stomach.

After four months in Harkness Hospital, Dr. Wheeler told her it was time to take the bandages off again. The first time hadn’t worked. In fact, it was worse. Everything looked all slanty and it made her dizzy, so they had to do it over.

“Finally,” she said. “Now can I sit up and move my head?”

Dr. Wheeler chuckled. “Yes, Jean, that’s what it means.”

That was the last time he chuckled that day. All during the tests he kept asking her, “How many fingers can you see?” Then he just asked, “Can you see my fingers?” Then, “What can you see?”

“Just light and dark. Shadows moving.”

He was quiet for a long time. She felt her breathing come in waves. It seemed the only thing she was sure of. “What are you doing?” she asked.

“Writing.” He sat down on her bed and took her hand. “Jean, I don’t like having to tell you this, but I don’t think we can do any better. I’m sorry. The retina wasn’t just detached. It was torn, too. That probably happened when you fell off that horse. It just made things worse. Right now we just don’t know enough yet about retinas to repair it.”

Her throat clamped shut so that she couldn’t speak. She felt numb.

“If you could have waited a few more years to have your trouble, I might have been able to do more for you.” His voice sounded tired, kinder than father’s, and the words hung in the air in front of her, strange and hollow, like the echo of a great bell.

“You mean I won’t be able to see, not ever?”

“I don’t think so.”

She had wondered how he might say it to her and now here it was, just like that: “I don’t think we can do any better. I’m sorry.” So it happened? It’s over? That’s it? Me? Me. He’s talking to me. She couldn’t swallow.