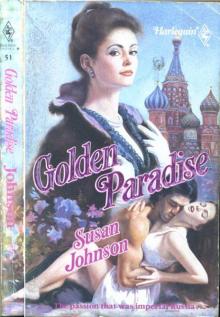

Golden Paradise

Susan Johnson

From Back Cover…

A woman unlike any other

The Countess Lisaveta Lazaroff seemed to fear nothing—not war, not marauding bandits, certainly not the scandalized whispers of polite society. And from the first, Prince Stefan Bariatinsky was fascinated by her beguiling mixture of innocence and sophistication. The splendid young officer was sought after by most of the ladies of the czar's court, but they held no interest for him now. From the battlefields of Asia to the ballrooms of Saint Petersburg, the prince could find no peace, for he was haunted by the memory of one silken night in Lisaveta's arms….

About the Author…

SUSAN JOHNSON

is a well-known writer of historical romances who has now, with Golden Paradise, returned to the setting that originally made her famous—the Russia of the Czars. She is an avid collector of books of all kinds, commenting, "they threaten to overrun the house." The nineteenth-century Russian writers are her favorites, perhaps the reason Russian settings for her historical romances have always been close to her heart. Research for Susan is "both a passion and a pleasure," and that love makes her historical settings and characters spring vividly to life. Susan and her husband live on eighty acres of virgin hardwood forest in North Branch, Minnesota, along with their horses, three dogs, one lop-eared rabbit and a very large piranha.

To Hafiz… whose work endured during his own times of turmoil and through the ensuing centuries because he spoke great truths and small, rose above narrow views, believed in a natural freedom of spirit and, perhaps better than most, understood the mysteries and passions of love.

With his most famous verse, I dedicate this story.

Oh Turkish maid of Shiraz! in thy hand

If thou'lt take my heart, for the mole on thy cheek

I would barter Bokhara and Samarkand.

Stefan in his own way was willing to barter as much….

Golden Paradise

by

Susan Johnson

Prologue

Karakilisa, Turkey

July 1877

The medieval fortress at Karakilisa, home to each powerful Khan of the region since the time of the Crusades, commanded the only natural elevation for miles. But over the centuries more civilized owners had refined its functional design, and within its rough walls an elegant white marble palace stood.

And inside that graceful palace, in a high-ceilinged, shaded room built to mitigate the intense summer heat, Lisaveta Lazaroff was packing—or, more aptly, directing the three serving maids in that task. In Javad Khan's palace no guest ever lifted a finger.

"This," she said, and "that," pointing at a single change of chemise and drawers. "And just one blouse, no petticoats." She was taking no more than the bare essentials, traveling light with only the contents of two saddlebags to see her through to Aleksandropol on the Russian border.

Could she afford the weight? she wondered, holding her favorite copy of Hafiz in her hand. No, she decided in the next heartbeat, she couldn't. But once the war was over she'd come back for everything she had to leave behind.

"You won't change your mind?"

Lisaveta turned sharply at the sound of the male voice. Then, seeing her father's old friend Javad Khan, she relaxed visibly. "No. Although it's no reflection on your hospitality," she added with a smile. Javad Khan's hospitality was in fact lavish, but his nephew Faizi Pasha had stopped to billet his troops for two days and had decided Lisaveta would make a fine addition to his harem.

"My apologies for Faizi," Javad said, advancing into the large room, which overlooked a fountained courtyard lush with blooming roses. "His father was Turkish."

This latter statement might seem oblique, but Lisaveta understood all the unspoken and disparaging nuances. Javad Khan, overlord of western Azerbaijan, was wealthy, cultured and Persian. He viewed the Turks as parvenu, perversely orthodox barbarians.

"I can protect you from Faizi," he said. "You needn't leave."

"Thank you," Lisaveta replied, choosing her words carefully. "But I don't wish to be the cause of enmity in your family." She also didn't wish to take the chance that Faizi and his troops might win this particular battle.

Javad shrugged. Family genocide was a cultural reality in his society, where power was often gained at the expense of numerous and bloody rivalries. "My tribesmen are more than a match for Faizi's troops." And as a man with a harem of his own, he couldn't be expected to understand Lisaveta's horror when faced with the prospect of being locked away in a harem herself.

"I don't want any bloodshed over my presence." She smiled again to soften her refusal. "It's best if I leave. Once the war is over I'll return to continue my research in your library. I'm so grateful you gave me the chance." Javad Khan's collection of Hafiz, Persia's greatest poet, was the most extensive in the world, the most lavishly illustrated… and the most private. Only she and her father had ever been allowed access.

"Your father and I were good friends," Javad Khan said simply. "And I've known you, my dear, since you were a babe in arms. My home is your home." His deep voice was without inflection, but she knew that he was quietly offering her. the full extent of his hospitality, including the formidable weight of his warrior tribes' military prowess.

"I know." Lisaveta's expression acknowledged the honor bestowed on her by his offer. "And if I weren't compelled by feelings more powerful than rational, I'd stay." Her golden eyes held his. "I hope you understand. With the Russian army garrisoned in Aleksandropol only a hundred miles away, I'd feel safer—" She didn't know how exactly to explain she wasn't willing to trust her life completely to his protection, that the risks of riding through the war zone seemed less daunting than Faizi Pasha's plans for her future.

Maybe that was it. If she left for Russia, she would be in control of her own life, however perilous her journey. In the grip of Faizi Pasha, should that terrible eventuality come to pass, his harem door would clang shut, the world would be locked out, and she'd be a prisoner until she died. She wasn't gambling one risk against the other; her flight was the result of prudently weighing alternatives. As a first-class rider she knew she could reach Aleksandropol in less than a day, and once there she could expect the aid of her countrymen.

Javad was silent for a moment, the serving girls standing at attention as they had since he'd walked through the doorway. For just a brief moment, Lisaveta, Countess Lazaroff, Princess Kuzan if she chose to use her mother's title, felt incongruously as if she'd fallen into a vignette from The Thousand and One Nights. Could she assert her authority against Javad Khan, who ruled in the fashion of a medieval prince, if he chose to disagree with her wishes? She would be defying a man familiar with life-and-death mastery over his people. And even as sophisticated as he was, the position of women in his milieu was subservient.

Raised by an indulgent father, educated beyond the standards of most men, granted not only the normal freedom of her wealth and position but the additional prerogatives her scholarship allowed, Lisaveta had lived a life distinguished for its independence.

She would rather die than be trapped in a harem.

"I would have had to leave within the month anyway, to attend the Tsar's ceremony in Saint Petersburg honoring Father's work," she said prosaically. "And the siege of Kars has been lifted, Faizi said. Now should be an excellent time to travel, since there's a lull in hostilities between Turkey and Russia. It's only ten hours," she added in defense of her position.

"The area is still alive with troops."

"I'll travel at night."

"The irregular cavalry raids at night. It's in their blood."

"Javad," Lisaveta said very softly, "I wish to leave, for maybe incomprehensible reasons—but I cannot stay."

Javad Khan was very tall, and the straight fall of his silk robes accentuated his height. He gazed down at her for a long moment. "Then you'll need an escort," he said into the quiet of the room. "And my best horses." He smiled. "And Allah's prayers."

Lisaveta grinned back, relieved and strangely elated. There was pleasure in taking action. "Thank you," she said.

His dark eyes beneath his white brows were amused. She'd always been a headstrong young girl, but maybe that was a portion of her charm. "You'll need some peasant clothes," he continued, his own grin matching hers. "If you look like that—" he indicated her gaily flowered summer frock and dainty blue slippers "—you'll be captured two miles down the road… for someone else's harem."

Chapter One

Russia, Transcaucasia

Hell would have been an improvement.

There was not a tree in sight, not a blade of grass, just a relentlessly barren plateau too close to the sun and too high for rain.

Prince Stefan Bariatinsky was hot. He was beyond hot. He was bone weary, sweating hot, exhausted hot.

And he'd been swearing under his breath for the last half mile.

"Are you going to make it?" Haci, his lieutenant, asked.

"Hell, no. I want a big funeral." Stefan smiled, mitigating the harsh severity of his face, which was swarthy by birth and further bronzed by years of soldiering for the Tsar. Although he had his tunic unbuttoned so that it hung open, his heavily muscled chest was sleek with sweat beneath the silver-trimmed uniform, and his leather riding breeches felt slippery against his skin. "With Gypsy girls to dance over my bier," he added with a facetious lift of his black brows.

Not that Stefan had ever restricted himself to Gypsy girls. He was in fact, next to the Tsar, the most feted man in the Empire, adored by a great variety of women, and not just for his rank and wealth.

He was the most fearless officer in the Empire.

And handsome as sin.

Too handsome, men said, watching their wives' eyes dwell on him.

Too handsome, jealous young ladies said, watching him flirt with a rival.

Too handsome, like his father, older wags remarked, remembering the scandalous ways of the elder Prince.

But impetuously charming, they all agreed.

"It's not much farther," Haci pointed out, for forty of the fifty miles from Kars to Aleksandropol were now behind them. "And in a few days you'll be at the lodge, with Choura dancing on your—well—wherever," he finished with a grin.

Stefan's Gypsy lover was waiting for him at his mountain retreat and she was capable of taking one's mind off any mundane problems. "That thought," Stefan returned, his mouth quirked in a smile, "might just keep me alive until Aleksandropol."

"You only have to last ten miles."

"Don't say 'only.' Right now it seems the end of the earth." Stefan shifted slightly in his saddle, flexing his broad shoulders in an attempt to ease the discomfort of aching muscles and fatigue. It was a hundred and two degrees, and he was so covered with dust that the sweat trickling down his body was leaving paths. His formerly white Chevalier Gardes uniform was now an indistinguishable color that would have been a court martial offense on the parade ground. But he and his personal bodyguard of Kurdish irregulars were riding north toward Tiflis, capitol city of Georgia, for a badly needed furlough after the three-month siege of Kars. Their first night's stop in Aleksandropol would at least afford him the luxury of a bath, food and a woman—in that exact order, his libido tempered by personal demands for comfort first.

The war in the east had ground to a standstill in the blazing heat of July, both Russians and Turks content with maintaining an attitude of mutual surveillance. Both sides in this war— begun by the Tsar in April to save the Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire from further massacres—were now bringing up reinforcements before resuming the campaign.

Meanwhile the Russian siege of Kars, Turkey's great fortress on its eastern border, had been abandoned and the Russian troops were retiring toward Aleksandropol for some desperately needed rest.

As the Tsar's youngest and best general, Stefan knew the Russians had begun the campaign with too few men, and after Tergukasoff's defeat at Zevin they couldn't afford another disaster. It was vital the troops were allowed some rest before hostilities were resumed.

When the war had begun in April, Kars in Eastern Turkey had been one of three main positions of the Turkish line on their border with Georgian Russia. Russian troops had taken one fortress and garrisoned it, but Kars had cost thousands of lives in vain assaults. The Chiefs of Staff couldn't agree on strategy. Coordination was a nightmare, since whenever reinforcements should have been called up or an assault planned, competing generals fought for control. Stefan's cavalry corps was the only unit to have continued success but at the cost, often, of more men than he could afford to lose… to staff blunders. And even his successes were viewed at times with jealousy.

Stefan had studied military history along with the more recent campaigns and had devised his own tactics to defeat the impregnability of earthworks defended by magazine rifles. To his men he was both a leader and a friend. "Come," he would say, not "Go," and he always explained the situation to them and told them what to do. His men knew he wouldn't ask them to do anything he couldn't do himself. He was viewed as unorthodox in his tactics and to many on the staff as a potential danger with his victories mounting.

But Stefan was weary of the bickering and rivalry among the general staff when he knew that cooperation was needed to win this war—cooperation and more men, sufficient supplies and improved armaments. Much to the displeasure of some of those in the High Command, Stefan had equipped his own men with captured Winchester rifles, when most of the Russian army was still equipped with antiquated Krenek rifles.

He sighed at the inequities and the pettinesses that were costing them thousands of lives. He needed this furlough to forget for a few weeks the awfulness of war and to recharge himself for the coming offensive.

The Turks, too, spy reports indicated, were licking their wounds.

After three months, very little progress had been made. Russia had won some battles. The Turkish army had dug in and built formidable entrenchments and had won some battles by rebuffing Russian advances.

But now Russia was stalled on their march west toward the Dardanelles. And Kars, the most modern fortification in the Turkish eastern border, had held fast against Russian attack.

For Turkey, this was a Holy War for Allah.

For Russia, a crusade to save oppressed Christians in the Ottoman Empire.

The gods for whom all the thousands of soldiers were dying hadn't deigned to give any signs.

Unless the blazing sun was their way of calling a temporary truce.

"Bazhis," Haci muttered suddenly and sharply.

Stefan turned in surprise, because they were now very near Aleksandropol and the marauding Turkish bands generally kept their distance from the cities. But when he followed the sweep of Haci's arm he saw them through the shimmering waves of heat. Fewer than his troop of thirty, he decided, quickly counting. Good. His next thought was accompanied by a twinge of unmilitary annoyance. Damn, there went his imminent prospect of a bath.

Despite his personal wishes, Stefan applied spurs to his black charger. With Haci at his side, they set off in pursuit, followed by his colorful bodyguard, each man the best young warrior of his tribe. All were sons of Sheikhs, their different tribal affiliations evident in the variety of their dress: the red-and-white turban of the Barzani; the green sash of the Soyid; the Herki's crimson and the Zibari's blue flowing robe; each man's horse trappings and brilliant garments streaming behind as they galloped across the plains.

Drawing his rifle from the cantle scabbard behind him as the distance between his men and the Bazhis diminished, Stefan sighted on one of the fleeing bandits. As he'd suspected, the marauders had realized they were outnumbered and were in retreat. None of the Turkish i

rregular cavalry chose to stand and fight unless they had vastly superior numbers; the native warriors preferred hit-and-run raids.

At the first barrage of fire from the Winchesters favored by Stefan's men, a Bazhi near the rear of the fleeing band flung away a black-clad woman he'd been carrying. With his horse falling behind under the double load, survival outweighed pleasure. The body sailed through the air, the covering shawl slipped away, and long rippling tresses of chestnut-colored hair flared out behind the catapulting form in a beautifully symmetrical fan. Stefan winced instinctively as the woman's body bounced twice before sprawling motionless on the sun-baked plain.

Hauling back on his reins, he tersely apologized to his mount for the sharp cut of the bit. As Cleo came to a rearing, plunging halt, his troop swept past him in pursuit of the Bazhis. Women weren't a commodity as valuable as other types of plunder to Kurdish warriors, and as the best mounted of the native tribes, Stefan's men obviously felt confident they could overtake their prey. Leaving them to their pursuit, Stefan slid off his skittish prancing mare to attend to the woman himself.

Bending over the small still form a moment later, Stefan decided she was merely unconscious rather than dead. Her breathing was faintly visible in a slight rise and fall of dusty drapery… although, jettisoned at a full-out gallop, as she had been, she could be severely injured. She was dressed in the conventional layers of clothing native women affected, the yards of enveloping black chador, the veiling dresses, vest and pantaloons. Reaching beneath the black and tentlike chador, he found her wrist and felt for a pulse… a pulse he discovered a moment later beating in a strong regular rhythm. Perhaps all the layers of clothing and flowing yards of material had cushioned her fall.

Carefully lining the shawl concealing her face, he scrutinized her briefly through the masking dirt and gray clay dust indigenous to the region. A superficial survey suggested she wasn't very old, probably quite young, since this rugged land aged one prematurely. Her hair, as he had noticed earlier, was considerably lighter than the customary native color. Perhaps she was Kurdish with that shade of hair, or maybe she had antecedents nearer Tiflis, he abstractly thought in a thoroughly useless reflection, as if it mattered what her parentage was.