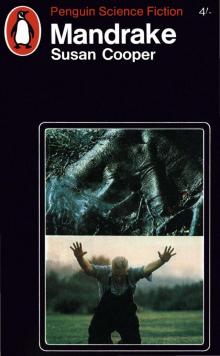

Mandrake

Susan Cooper

Penguin Science Fiction 2491

Mandrake

Susan Cooper was born in Taplow, Buckinghamshire, in 1935 and educated at Slough High School and Somerville College, Oxford. She was the first woman editor of the undergraduate newspaper, Cherwell, and later became a reporter and feature-writer for the Sunday Times in London. In 1963 she left its staff to marry an American, and now lives in the United States, though still writing principally for British readers.

Her first novel was Mandrake and her most recent Behind the Golden Curtain, a commentary on American life. Susan Cooper has also written a book for children, Over Sea, Under Stone, and was a contributor to Age of Austerity: 1945-51 (published by Penguins).

the characters in this book are entirely imaginary and bear no relation to any living person

Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth,

Middlesex, England

Penguin Books Pty Ltd, Ringwood,

Victoria, Australia

First published by Hodder & Stoughton 1964

Published in Penguin Books 1966

Copyright © Susan Cooper 1964

Made and printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd, London, Reading and Fakenham

Set in Monotype Baskerville

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Time will say nothing but I told you so

W. H. Auden

Table of Contents

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

About Susan Cooper

Bibliography

Part One

Queston was never quite sure afterwards whether he really heard the shot. Probably it was the noise of the bullet smacking into the concrete wall three feet behind his head; the small crunching thwack that made him turn and notice the white scar in the blue paint, and the white grains still floating in the air. Then the shouts came, farther away, high and shrill over the boom of the amplifiers’ voice still tolling: ‘Pan American Flight 201 to London, passengers to Gate Six, please…’

There were confused shouts, from a struggling knot of figures behind the immigration barrier. He turned back, buffeted by the crowd, and caught sight briefly of the man held there by police. A thin face, twisted with yelling, stared up from a body bent double by the law’s willingly expert blue-shirted arm. The scream came suddenly clear as the man vanished, dragged out of sight: ‘Murderer! Murderer…!’ It was an English voice.

‘What gives?’

‘What’s going on?’

‘Someone took a pot shot at a guy—’

Queston was taller than most of the other passengers; they bubbled under his gaze in a quacking sea. Tailored American matrons with blue hair, two small blonde English girls with jaws like horses, round bald men in grey suits. A big mid-Westerner near him, impassive between crew cut and bow-tie, said loudly, public and important: ‘He was trying to get that guy over there. The dark one with the cops. I saw him. Fired one shot before they grabbed him—real nutty-looking character, missed by a mile…’

‘Jeeze, we might have been killed—’

‘Who was it? Who’s the guy he shot at?’

‘Hey, I think I’ve seen him before—isn’t he a film star or something?’

Like smiling sheepdogs the airline stewardesses came persuading them to move on down the long corridor, reciting gently, ‘Flight 201, please,’ as if nothing had broken the airport’s scampering routine. Queston side-stepped an imperturbable sweet-threatening blonde for long enough to stare at the man the mid-Westerner had indicated. He saw a small group of men by the barrier, talking to the immigration officer who had put him through so peculiarly searching an interrogation five minutes before. Among the uniforms and the holsters there were several men in dark suits, with the indefinable self-contained look of travellers. One, the tallest, stood clearly the focus of the group—youngish, dark-haired, with a face at once foxy and strong. He was talking quickly, one clenched hand frozen hard against the palm of the other; it was the attitude of a man suppressing some large emotion he did not want others to see released.

Not surprising, Queston thought, if he’s been shot at. As he watched the man an echo of memory flicked into his mind and away again, to twitch irritatingly behind his thoughts as he let the stewardess turn him finally towards the plane. ‘Flight 201, sir? This way…’ Somewhere he too had seen that face, sometime during the last five years. But a film star? No—something very different…

Outside, the aircraft lay, a dull grey cylinder patched red, yellow, green by the heat of Mach 3 speed; the huge engines nestled at its tail and the nose pointed, menacing, like a needle-sharp horn. He thought: They should call it Unicorn. But instead they called it 1010: ten-ten; he had travelled in his first only the day before, on the way to New York. In the territory where he had spent the last five years, there was no use for anything but the older subsonic planes.

Inside the cabin, subtly transported from high summer to a cooler, gentler artificial sunlight, he settled back to let the music from the hidden amplifiers lull him gently half-asleep. It wafted him through the mild prickle of air pressure; through the small lurch of take-off, the sudden change of element that somehow was still there to be felt even without windows to show the ground falling away. He had always liked the frisson of freedom which that release gave.

The seat beside him was empty; on these midday flights there was always space, they had told him, even in tourist class. So when the touch on his arm came he thought it was the blonde stewardess, and looked up with the beginning of a smile into the face of a strange man: dark reddish cheeks and pale lashless eyes. Hastily he dropped the smile, but saw a broader one on the stranger’s face: a grin, almost a grimace, of wide welcoming teeth.

‘Dr Queston?’

‘Yes,’ Queston said warily.

‘David Queston? The anthropologist?’

‘Yes. But I’m sorry, I don’t think I—’

‘Brunner,’ the man said. ‘Klaus Brunner. You and I have met several years ago, Dr Queston, I think in 1970. Before you left to bury yourself—if you will forgive me—so wastefully in Brazil. Or perhaps it has not been a waste. At any rate I am glad to see you coming home. You remember me, perhaps? ’ He sat, still smiling, on the arm of the empty seat.

And then Queston did remember him; and remembered in the same moment the face of the man attacked at Kennedy; and knew suddenly what was coming next.

‘I am travelling with the Minister,’ Brunner said. He gave the word an obsequious sound; a Teutonic reverence for office. ‘We have been on a brief mission in the United States—most successfully, I am glad to say. The Minister would very much like to meet you—he was delighted to find your name on the passenger list. He sends me to ask if you will give him the pleasure of your company during the flight. You are not busy, I hope?’

Queston said non-committally: ‘I imagine you’re travelling first class.’

Brunner chuckled. ‘We are—and no one else. There is therefore plenty of room. And anyone who is with the Minister… Please?’

‘Why not? ’ He stood up, unfolding himself from the narrow seat, and followed the stocky little German down the aisle. At the barrier leading into the first-class cabin the stewardess, smiling respectfully, held back the door to let them through.

Against the padded head-rest of the seat where Brunner stopped, Queston saw the lean dark head of the man who had been in the centre of the group he watched at Kennedy; the man at whom t

he shot had been fired. He realized now that it was in the few newspapers to have come his way in Brazil that he had seen this face, pictured from Britain: young, bland, tough, always inscrutable, with no expression but confidence behind the large dark eyes. The face seemed thinner than it had done in the pictures, looking calculatingly up at him now.

Brunner said stiffly: ‘Minister, may I introduce David Queston. Queston, this is Mr Mandrake.’

He had been away from England for a long time then, too, on the day he had first met Klaus Brunner. He had not known what had been going on. Not that there had been any reason, then, to look for sinister motives at work on the country. Perhaps there was still no reason now. Well.

It was in Oxford. On each of his few trips back to Britain in the last fifteen wandering years he had come there, briefly. He had few friends, and fewer that he cared to seek out; but James Thorp-Gudgeon was always an entertainment. Fat and imperturbable, he sat in his comfortable set of college rooms like an amiable Buddha, dispensing high-pitched paternalism to a new set of disciples every year. Queston liked to go back to be amused: and perhaps to be reminded, through Thorp-Gudgeon’s malicious prattle, of the reasons why he would always prefer another long remote expedition in a joyless climate to settling down in the British academic life.

He had arrived at Oxford by train, to find an unaccountable peace in the streets.

‘James,’ he said, across the book-strewn table and peeling leather chairs, ‘what on earth’s happened to the traffic? I saw hardly anything but bicycles on the way from the hotel.’

Thorp-Gudgeon emerged from a cupboard with a decanter of port, his broad moon-face slightly flushed by the effort. ‘Bliss, dear boy. Absolute bliss. Didn’t you know we’d solved our problems? It must be nearly a year now. They tried to build that ridiculous road through Christ Church meadow again, and Oxford made such a fuss that the P.M. re-created the Ministry of Town and Country Planning. Not before time, I must say. The result is that we have virtually a walled-off city. Free of through traffic, at any rate. Delightful.’ He eased himself into an armchair, and stretched his little legs out in front of him comfortably.

‘Pretty well free of trains too. I had the dickens of a job getting here.’

‘If you’d come by car,’ Thorp-Gudgeon said, ‘you’d have found yourself stopped on the perimeter. Only essential traffic is allowed in. Eventually we shall have roundabouts built at every exit, to save the congestion while the police turn people away. The roundabouts will be blind, d’you see, on the Oxford side. We shall leave one road open to the north and south, at St Aldate’s and St Giles’s, to let inside traffic out—with permits, of course. But that will be all.’

Queston blinked at him. ‘You need a permit to get out?’

‘O yes,’ Thorp-Gudgeon nodded placidly, and sipped his port. ‘If one has a car, that is. Few people have, now. But of course, dear David, you are always some years behind with the news.’ He radiated geniality across the fireplace. Twenty years earlier he had been Queston’s tutor at Birmingham University—a brief and unwilling sojourn of which he preferred not to be reminded—and had been treating him like a favoured and precocious pupil ever since. But while Queston roamed the Far East and South America, on research projects for a dozen assorted universities, James Thorp-Gudgeon had chosen to put down roots: and within weeks of his appointment at Oxford he was a fat panjandrum, dispensing aphorisms, anthropology and Chablis in equal quantities, and caught in as tight an emotional bond to Oxford as if he had held a chair there for fifty years. Queston, who had no parents, wondered sometimes in lighter moments if he thought of Thorp-Gudgeon as his mother.

He said, grinning, ‘Well, I hope you’re happy now. The reactionaries have won at last.’

‘Not at all. This is highly progressive. The Minister—’ There was a knock at the door.

‘Ah,’ Thorp-Gudgeon said. He heaved himself out of the chair, looking down with an oddly sly smile. ‘This is someone I wanted you to meet, David.’ He called. ‘Come!’

The man at the door was chunky, square-shouldered, with dark hair cut flat and short across his head. The only startling thing about him was his face: two patches of red glowed high on each cheekbone, spreading to meet across his nose, and although his eyebrows were heavy there were no lashes to his eyes. He had a reptilian look. Queston tried not to stare.

‘Good evening, James,’ the man said. It was a throaty accent.

‘Come in, my dear fellow, come in. You don’t know David Queston, I think. David, this is Klaus Brunner, of St Catherine’s. One of our best young architects, if he will forgive me for saying so.’

He buzzed over the decanter like a benevolent bee. ‘Klaus and I are among the conspirators, David. That is to say, we are both members of the Ministry’s advisory committee here. Partly responsible, I’d like to believe, for the developments I was telling you about. We’ve worked very closely with the Minister ever since the first Oxford plans began.’ Queston grinned at him. ‘And since when have you become a traffic expert? I can see Mr Brunner’s natural connexion with the business, but an anthropologist…’

Brunner said seriously, in his thick voice: ‘The Oxford Committee is a research group of a rather unusual kind, Dr Queston. Patterns of human behaviour are as important as any architectural aspects of town planning. In some areas of our work especially.’

‘There are other areas?’

‘O come, David,’ said James Thorp-Gudgeon reproachfully. ‘You must have heard something about Mandrake’s record, even in Brasilia.’

‘Mandrake?’

‘The Minister. Excellent man, really excellent. An Oxford man—first in Greats at Trinity. He’s proved himself head and shoulders above the rest of the Cabinet in the last three years—tremendous drive, the way he’s put the country back into working order. Administratively, you know.’

Brunner said, accepting a glass and sitting stiffly in a high-backed chair: ‘Let me describe to you, briefly, Dr Queston. The scope of the Ministry is wider than before. It stemmed from concern over the way many cities were being choked by increased traffic and poor roads, London in particular. That is why I think Mandrake’s work has been so much welcomed. He has not only made changes by his own powers, he has initiated new legislation. The whole country, for instance, is divided firmly into seven regions now nominally under the aegis of the Ministry of Town and Country Planning, for the purposes of local government—and to administer education, roads, and many things formerly directed from Whitehall by the Home Office and the Board of Trade.’

‘The Home Office—’ Queston frowned, puzzled. ‘Mr Mandrake sounds as if he’s putting us on the road to federal government. He’ll surely meet a lot of resistance—from the Civil Service if no one else.’

Thorp-Gudgeon chuckled fatly. ‘The wind of public opinion can blow hard even down the corridors of power—ah no, this was an obvious step, just too long delayed. After all, there had been development councils for industry in Scotland and north-east England for years, hamstrung by having too little real power. Local feeling everywhere rose immensely when the proper regional councils were formed. We’re an ancient country, David. I’ve always thought the old kingdoms still existed under the skin. Mercia, Wessex, Northumbria, and so on. Think of the Roses cricket match—’ Brunner struck a match with a sharp crack to light a cigarette; the reflection glowed briefly in his pale eyes.

‘These things are still only new, of course. The most effective work has been done in making the cities able to breathe. Stopping all office building in Central London, and cutting off other cities from through traffic on the Oxford pattern. York, Gloucester, Durham, Cambridge, and some others. You must visit them, if you are in Britain for long. You will hardly recognize them. The university towns in particular are delightful now. They have given us some of our strongest support.’

Queston shifted in his chair. He could feel his mind teetering on the edge of boredom. Had Thorp-Gudgeon really thought he would enjoy this pompous little

German? Of course, James had always loved plotting and planning, the machinations behind a university election; he had revelled in the lobbying over the Oxford road problem for years. He must be a natural for the camp of the efficient Mr Mandrake.

Then Brunner said abruptly: ‘I very much admire your work, Dr Queston. The book on New Guinea was the last one, was it not? James always says you are the greatest wanderer he has ever known.’

‘And the most successful,’ Thorp-Gudgeon said without rancour, smiling from his deep chair. ‘It takes a great man to produce popular anthropology and at the same time retain the respect of the academic world.’

‘Ah, give over,’ Queston said amiably. ‘You old snob, you know the only reason you still speak to me is that I’ve never got to the point of making television films.’

‘My dear boy, you could become a film star of the utmost eminence and I should never know.’

The dark-panelled room was growing murky as the light died outside. Thorp-Gudgeon reached up and turned on a standard lamp beside his chair.

‘The books are very interesting,’ Brunner said persistently, leaning forward with his eyes on Queston’s face. ‘Mr Mandrake was much intrigued by your examination of patterns of migration, I remember. He will be in Oxford for a committee meeting in two days’ time—if you will still be here I know he would be very glad of the chance to meet you.’

Queston shook his head. ‘I have to go back to London tomorrow, I’m afraid, and then abroad again.’ And sharp-witted politicians aren’t my cup of tea, thank you very much, he added to himself.

‘I didn’t know he was coming,’ Thorp-Gudgeon said eagerly. ‘Is this Wednesday’s meeting in the Town Hall?’

‘Yes. He wants to talk about the resettlement plans, I gather. There are a few particular points… but I will tell you about them later. Let us not bore Dr Queston.’