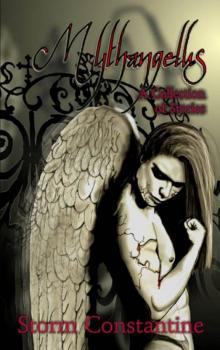

Mythangelus

Storm Constantine

Mythangelus

A Collection of Stories

Storm Constantine

Stafford England

Mythangelus: A Collection of Stories

© Storm Constantine 2009

Smashwords edition 2011

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real people, or events, is purely coincidental.

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.The right of Storm Constantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

http://www.stormconstantine.com

Cover Artist: Peter Hollinghurst

An Immanion Press Edition published through Smashwords

http://www.immanion-press.com

info(at)immanion-press.com

Immanion Press

8 Rowley Grove, Stafford ST17 9BJ, UK

Contents

Paragenesis

The Law of Being

The Green Calling

Angel of the Hate Wind

The Feet, They Dance

Return to Gehenna

A Change of Season

How Enlightenment Came to the Tower

By the River of If Only...

Fireborn

Heir to a Tendency

Spinning for Gold

The Nothing Child

Living with the Angel

The Oracle Lips

Story History

Paragenesis

I have scars upon my left hand, but not upon my right. If I hold my hands up to the eternal sun, light shines through the flesh. But there is no flesh. I am idea, essence. I am the flash of sunlight off chrome; I am the seasons; I am the shadow beneath the eaves; I am a scrap of litter scratching across cracked asphalt. No, I am bones and blood. I am crude and heavy. I am what I am.

When I was sixteen, I ran away from my leaf-shrouded home in the enclave for the rich, about twelve miles from the city centre. Perhaps it began as a suicide bid. All I did was move my limbs, without conscious volition, toward the wilderness of stone and glass that circled the city itself like a plague. It was the hinterland of decay, spreading both outward and inward, threatening city core and enclave alike. People could lose themselves there, and I wanted to be lost.

I remember that day. She was standing at the kitchen sink with her back to me. She could always sense when I walked into the room. I’d see her spine tense beneath its dress of cotton, its caul of skin. How cruel had Mother Nature been to make her spawn a child she could only fear? Blessed was the day when she no longer had to touch me; when I could feed and bathe myself, tie my own laces, rub my own hurts. I could not despise her, for I shared her bewilderment, her bitterness. When I’d been born, no doubt she’d decided to make the best of it. I was a beautiful child, but for those hidden abnormalities. Later, she probably realised that even monsters could be beautiful. My father was a non-entity, consumed by work. We rarely saw him. Our home always seemed empty when she and I were in it together. The spaces between us were too great, and as I grew older, they became gulfs.

On that final day, I could not bear to see that stiffening spine any longer. She had birthed me and raised me; now her responsibility was over. I turned around and walked away; out of the shady house into the sunlight; past the bike lying on the tarmac, where a few red leaves had drifted down; past the rope that hung from the old willow, still swinging and where I never played. The street was devoid of children; empty. Empty. This had never been my home.

On the horizon, a grey green cloud hung above the city. It was a walk of about four hours to reach it along the main highway. Sometimes, a bus might come, rattling and armoured, but not very often. People with eyes like pebbles rode the bus; not coming from anywhere, going nowhere, just riding. Perhaps they thought time would stop for them in that way. I would not ride the buses, for I was afraid that if I did, I would be absorbed into that shadow community and never leave it. Another freak on the back seat.

It was mid-morning when I left the enclave, and already the sun was fierce in the late summer sky. At the high metal gates, the eyes of the guards were hidden behind black glass. They stood motionless, like automatons. I passed between them, showed my ID card, and the gates slid open. A minute later, someone else might come by, and the guards would come alive. They’d touch their helmets, grin to show their white teeth and utter a pleasantry. But not for me. After I’d gone, one would say, ‘That’s the weird kid from Acacia’, and the others would sneer.

I walked along the slip road that led to the highway. It seemed hotter beyond the enclave, and the air shimmered about me. Vigilantes had strung someone from a pole. I could see the body dangling on the other side of the road, surrounded by trees. A cloud of flies danced around it. Beneath it, someone had left some artificial flowers. Perhaps the enclave guards, high up on the gates and watchtowers, had seen it happen.

I cannot remember feeling anything then. I just walked, kicking up dust that smelled of metal and age, buffeted by the searing wind of passing vehicles. After an hour, a truck stopped to offer me a lift. The back was filled with people, crammed together like pigs on the way to a slaughterhouse. They were probably just crop-pickers, returning to the city. My feet were aching, so I hopped up into the back. Certain people always picked up on my strangeness, and this occasion was no different. My fellow travellers were like frightened animals: I saw furtive shuffling, and nervous eye movements. I didn’t say anything. Eventually, one of the men offered me a cigarette and I smoked it, looking out through the truck canopy at the passing road. My mother will have missed me by now. Her relief will fill the silent house, washed by waves of shame. She will grip the edge of the sink and blink at the garden, where the sprinkler slowly turns on the lawn.

I did not resent being born different. The resentment came from other people’s reactions. I was so ordinary in most respects. Dogs had never liked me; we could never keep one. Sometimes, things happened around me over which I had no control. It wasn’t my fault. It was the look in her eyes. I made the saucepans fly once, but not toward her. She just screamed, her hands pressed to her face, staring at the mess on the floor. Other kids didn’t like me very much, despite my parents’ efforts to find me friends. I didn’t mind being alone. I’d tell my mother things she thought were her private thoughts, and then her mouth would compress into two white lines. Later, I’d hear her telling my father about it: ‘He must listen to us, for God’s sake! Do something!’ I didn’t listen. I just knew. It was like she told me things herself without words.

It was the doctors I hated the most. There was nothing wrong with me; I wasn’t ill. But my mother kept taking me back to that neat office that smelled of nothing, and let the white coats prod at me. I said, ‘just let me be’, and they would smile tolerantly, spreading my legs on the table for another look. They must have taken a hundred photographs.

‘It isn’t Froehlichs syndrome,’ I heard a doctor say to my mother, ‘because apart from the genital abnormalities, there are no other physical deformities.’

Her reply: ‘Then what is it? Can you operate?’

‘That is a decision your son will have to make for hims

elf later on. We have counsellors...’

She thought I should have been twins: a boy and a girl. But it wasn’t that.

I got out of the truck on the outskirts of the city, in an area called the Longhills. Once, it would have been a thriving neighbourhood; now a ruin and an ideal place to hide, to think, to do whatever would come next. Tall buildings with broken crowns reached towards the veil of evil cloud that always hangs above the city. I think it is the city’s aura, an expression of its soul, soiled and poisonous. The people who live in that place are barely human, but then I had been taught to think that neither was I. Perhaps this was the place where I belonged. I wanted to cast off the trappings of affluence and live close the edge of survival. Discomfort did not bother me.

I walked as best I could along the sidewalks, avoiding debris, bundles of cloth that may have been corpses and the smouldering remains of fires. What did people burn here? Sometimes, it seemed they burned their own possessions. I saw fragments of books, jewellery and crockery blackened among the embers. The smoke was toxic. Someone had burned a wasps’ nest. A substance like syrup leaked from its collapsed mass. I saw few people. They kept out of the sun during the day. They slept then. Welfare trucks occasionally slid across an intersection ahead of me. They might contain bodies or miscreants or supplies. Perhaps all three at once.

At three o’clock in the afternoon, when the sun was at its most vehement, I stood in the centre of a street and looked up at the sky. Buildings loomed over me, derelict and rotting. I wondered what the point of it all was. Why do we continue to live? What drives us to survive in an environment so hostile to life, an environment we have made for ourselves? Civilisation was a Leviathan whose limbs were too weak to support it. Now it sank to its knees, bones cracking beneath its weight. And all who rode the Leviathan were tumbling down, their screams thin like that of insects. My difference was just one more symptom of this fall. Our purity was mangled and dysfunctional. In those moments, I saw myself as the avatar of the world’s destruction, a cruel joke in the distorted form of the primal human. I could do as I pleased, for it did not matter what would happen to me.

Soon, I began to feel hungry, but willed the pangs away. I could see no way to feed myself. It was cleansing to be able to step aside from human needs. I felt excoriated, but also renewed. For a while, I sat inside a broken building, where the walls were black. I listened for sounds: the faraway throb of rotor blades, the occasional human cry, cut off short, and once the distant bark of a dog. I watched the sun slide down behind the splintered towers, and thought how in the enclave, the day would be drawing to a close. Men would be emerging from the units in the nearby industrial park. They would climb into their sleek transporters, hail a manly good-night to the guards on the wall, and drive the short distance up the tower-studded avenue to the gates of the enclave. Here, wives who sought to enact the rituals of a past Golden Age would be waiting in kitchens that were devoid of stain. The women wore aprons and smiled at their children, keeping back the pain, the fear, the utter chaos that massed on the horizon of their fantasy world. None of it was real, but then I had never really conspired in my parents’ dream. My very existence cracked its fragile shell.

At dusk, a gang of girls stole in through the windows of my sanctuary. They saw me crouching in the rubble, which I quickly realised was their rubble, and began to snarl at me and utter strange ululating cries, their bodies dipping and rising like snakes. Their leader rushed at me a couple of times, brandishing a knife near my body, but I sat as still as I could, looking at her face. Presently, she came to a decision and gestured for her minions to get on with their business. They unfolded loot from tattered sacks, and set about dividing it amongst themselves. The leader flicked glances at me occasionally. I recognised something within her that later I identified as the indomitable human spirit. Society no longer existed for her, yet she continued to thrive, albeit in a debased fashion.

The girls ate and laughed together, handing round a plastic bottle of murky liquid. After an hour or so, their leader offered it to me. It was a vile, base alcohol that left a trail of fire in my throat and tasted only of chemicals. The girls asked me nothing about myself, even though they must have made judgements about my cleanliness, my neat clothes. They were separatist females who hated men. They could have killed me, perhaps, but it seemed they recognised something within me with which they felt comfortable and could accept.

I ran with them for a week or so, raking over the ruins, pillaging the debris. They seemed to repel rival male gangs by the strength of their voices alone, using a repertoire of chilling screams and cries. Boys would lope away from them like chastened dogs. Often, the leader would climb to the highest, most precarious point around and stand there with arms outflung, uttering a world-filling shriek of anger. They did not know about despair. I envied them.

In the asphalt wilderness of Longhills, there were few adults. Perhaps they had wisely moved away, or else been killed. Sometimes, choppers would drone over the streets and emit a stinging spray, which the girls told me was supposed to kill disease. Why would the city authorities bother? I didn’t believe it. The spray probably just killed fertility.

I felt more at one with the desperadoes of the wilderness than any of the people who hid within the enclave. It was because these outsiders expected nothing and gave little in return. They did not make demands upon one another. Co-existence, and therefore a certain amount of co-operation, was the only remaining aspect of community. Pleasure was without contrivance: a good find among the rubbish; a chance meeting with a group who had something to barter; a basement found untouched, like an unopened tomb full of treasure; an abandoned welfare truck still laden with vitamin-enriched gruel. We were grave-robbers, really, for most of humanity had already died in that place. But I liked the simplicity and honesty of their lives, the fact they did not judge me.

One day, one of the gang was shot by a sniper and the leader told us we would have to move area. A sixth sense told her this was the beginning of something bad. So we gathered up what little we had and left Longhills behind, burrowing off through the darkness, and into another decayed sector called Coldwater Valley. It must have been an industrial complex at one time, and here the survivors were older and hostile to strangers. We prowled carefully between the arching metal structures that were now smothered with tendrils of quick-growing vines. Echoes were strangely muffled by the vegetation. Any human group we came across yelled and threw things to repel us; we were not welcome. Finally, one group, crazier than the rest, directed a fire cannon on us and killed all but five of us. Our leader was among the fallen; a blackened crisp in the road. How quickly life can be expunged. It seemed inconceivable that what was left of our companions had ever housed souls. We, the survivors, went back the way we had come, but it was the end of our group. We split up, and I went alone deeper into the madness of the ruined land that surrounded the desperate core of the shrinking metropolis. Its towers seemed to have huddled together, as if in fear.

There was much activity in the air nearer to the city core. Choppers roared through the skies, and once I saw one crash. People emerged from the jumbled ruins like cockroaches and swarmed all over the wreckage, picking it clean. I did not look like an enclave boy any longer. My head was thatched with lice-infested hair; my clothes were tatters, to which I was forever adding more layers, whatever I could find. I had learned to snarl in the way that meant, ‘stay away if you value your health.’ I also learned much about myself. Because the convenient utensils of life were no longer available, I was forced to live on my wits, and in this way discovered that the boundaries of my difference were much further than I had imagined. It began this way.

I’d been going through the belongings of a dead man on the street, who had died of a sickness rather than murder. He had many treasures, which I was greedily transferring to my own pockets. Then a group of tearaways came slinking along the spiky walls around me, uttering low, hooting cries. Their message was for me to leave, to aba

ndon my find. I do not think they would have attacked me if I’d simply obeyed this request. But there was too much for me to leave. I growled back. They must have thought I was mad; there were at least seven of them. Their leader dropped down from the wall and sauntered toward me, looking to either side all the time. I remained hunkered down beside the corpse, my hands dangling between my knees. I did not feel afraid at all. It was as if there was someone else inside me, far wiser than I knew; someone fierce and confident. An arrow of indignation flew out of me, and somehow touched the crumbling substance of the wall behind the gang leader. There was an explosion, a gust of dust and rocky debris, and then my would-be attacker was on his hands and knees before me, his head hanging down. He shook his hair and drops of bright blood flew out. At once, I jumped to my feet and snarled. My eyes felt full of sparks that I could shoot like bullets from a gun. The gang just melted away, dragging their fallen leader with them. After this incident, I felt so much stronger, safer.

Perhaps I underestimated my strength.

Some days later, I found a hole for myself deep beneath an old department store. It had been cleaned out thoroughly years before, but some people must have lived there for a while, because I found a few mattresses, some of which had not been burned. Rags had been hung from metal beams in what remained of the ceiling. It was a musty labyrinth full of silent ghosts. I imagined it had once been home to a whole community, who had either been smoked out or died from some contagious infection. There were no bones about as evidence, but the wilderness scavengers are very thorough, so that meant little. In this place, I made myself a nest. I did not think about the future, but took simple pleasure in surviving from moment to moment.

The wilderness was the garbage heap of the world, yet I learned to see beauty in it: the different colours of the sky at various times of day and how they conjured sculptures from the rubble; shining through blown out windows; making a cathedral of light of the starkest structure. The passing of civilisation in itself was a wondrous thing. I would walk the cracked streets marvelling at the way stringy vegetation was slowly reclaiming the land. Mother Earth had learned the saying that revenge is a meal best eaten cold. She was implacable, eternal, and the green tidal wave of her reclamation was evidence of humanity’s frailty and insignificance. The people had regressed, but in their barbarity possessed a startling innocence. The complex rituals of life had been pared away, and if the people were dying, at least they would do so with swift dignity, rather than being hooked up to machines in a long coma of slow decay. Those who lived in the cities, the enclaves, were deluding themselves. They should give themselves up to the inevitable. I thought I too would soon die, and these were my last days. Each one dawned fresh and vital. I wanted to experience life through my senses to the full, and because of this, learned how my touch was death.