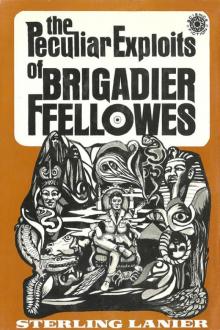

The Peculiar Exploits of Brigadier Ffellowes

Sterling E. Lanier

the Peculiar Exploits

of Brigadier Ffellowes

Ffellowes 01

( 1972 ) *

Sterling Lanier

Contents

Introduction

His Only Safari

The Kings Of The Sea

His Coat So Gay

The Leftovers

A Feminine Jurisdiction

Fraternity Brother

Soldier Key

Book Information

INTRODUCTION

Fashions come and go in literature, as in all the other arts. Some leave their mark; some are forgotten, together with the writers who created them. But one thing is certain, whatever else changes. There will always be a welcome for the good, old-style, traditional storyteller, whether he peddles his craft round the campfire, in the banquet hall, through the printing press, the TV tube, the video cassette—or with the aid of some technology as yet unborn.

One of the major influences on my own writing career was the great Irish fabulist Lord Dunsany. I do not deny—indeed, I proudly proclaim—that his ingenious Mr. Jorkens was in no small way responsible for my own Tales from the White Hart. The characteristics of a good Jorkens story are that it should take place in some unusual but vividly described locale, that it should be incapable of disproof—despite frequent attempts by its auditors—and that it should cast grave doubts on the commonly accepted view of the universe.

Lord Dunsany died in 1957, but a part at least of his mantle has descended upon Sterling Lanier. This is not to say that Sterling's "Brigadier Ffellowes" is a carbon copy of Mr. Jorkens (he is in almost every way a much more respectable person) and is always in a position to buy a drink for himself. But when I came upon the Brigadier in the pages of the magazine Fantasy and Science Fiction, I felt again a frisson of wonder and excitement I had missed for a couple of decades.

It is a great pleasure, therefore, to have all these stories collected into one volume, and I look forward to reading them again. However, 1 do not propose to do so when I am alone in an isolated house on a stormy night, when the low-hanging moon is intermittently obscured by what may, or may not, be clouds ...

So don't blame me; you have received fair warning.

Arthur C. Clarke

New York? November 24, 1971

HIS ONLY SAFARI

Mason Williams was in great form that evening. Or so an admirer would have described him, if he'd had any admirers. A lot of us in the club were still trying to find out how he'd ever been elected in the first place. The election committee, of course, will never say anything, but we were pretty sure they had blundered and were now pretending not to notice it.

Anyhow, Williams had just come back from Africa. He had bought himself a complete safari while there, the iced champagne and hot bath kind, and gotten himself a lot of stuffed animal heads, also purchased, if our suspicions were correct.

"Yes, I went alone," he brayed, so loudly that you could hear him across the library. "Real hunting, just me and the white hunter, two 'pros,' if I do say so."

"Since the hunter was being paid, he couldn't refuse to go along, now could he?" said someone in a perfectly audible aside. Williams got red, but refused to take notice. He was going to tell us all about it if it killed him.

It was pretty bad. I'm no hunter but I knew enough to know Williams knew absolutely nothing. Bits of his tale filtered through despite my attempts to read a paper.

"Used a Bland .470 express at three hundred yards on that baby!—Have to watch your step with Kudu—The hunter told me that Grant's would be a near record—Slept with loaded guns because lions were prowling around—Et cetera, et cetera."

On and on it went. No one was really listening but we were all damned if we'd allow Williams to drive us out of the library. Besides being warm and cosy there, it was a foggy, November night and the city streets outside were dim and dirty.

Brigadier Ffellowes' even voice cut in neatly during one of Williams' infrequent pauses for breath, and we all sat up and felt considerably more cheerful. Our retired English artilleryman had made one of his usual unobtrusive entrances and was toasting himself, back to the big fireplace, a gentle smile on his ruddy face.

"I wonder if you glimpsed a place I visited once, Williams?" he said in a musing tone. "A tribe of dark, hawk-faced men lived there in an ancient, ruined city. They were ruled by a white, veiled priestess who made claim to some incredible age. Why, it must have been in the very area you were hunting over."

Williams had never read She, or much else except market sheets, but this was too raw even for him.

"I suppose you know all about Africa," he said furiously. "After all, you British used to practically run the place until the natives got wise and ran you out. Probably you got some great sun and sand African hunting stories, too, General." (He knew Ffellowes hated being called 'General.')

"Why not give us one, Pal?" he went on. "A lousy American businessman can't hardly compete with a real pucker say-hib, eh wot?" Williams is a horrible man, honestly.

Ffellowes never batted an eye. Nothing infuriated Williams more than the realization that nothing he could say seemed to bother the Englishman. Now the Brigadier kept his serene smile as he drew himself an armchair and sat down near us. Very tangentially, he somehow managed to make a circle of chairs, so that Williams was left standing outside it and had to wedge himself half under the mantlepiece so as to even hear.

"I only once ever went on what might be called a safari," he said, "And my chief memory is not of heat, oddly enough. It's of cold, cold and mist, weather not unlike tonight, don't you know. But the mist was both thicker and wetter, as well as cleaner, of course. And the quiet was nothing like the city. Oh, that quiet!"

He was silent for a moment. The faint hooting of traffic was the only sound in the room. Suddenly, Ffellowes' gift for dominating a group had started operating again. His precise, level speech resumed abruptly.

"I was up in the Aberdares in December of '39, more because no one else was handy than for any special skill of my own, as will become apparent.

"Any of you know them? Well, they are a range of forested hills in Kenya that go quite high in some places and lie about fifty miles west of Mount Kenya itself. There is heavy forest up to eleven thousand feet in many places, and surprising amounts of big game, bongo, some Cape buffalo and even elephant. Leopard, of course, but no lions, unless poor Gandar Dowar was right and an unknown, small, spotted species used to live there.

"Into this area I had been sent by His Majesty's Government to look for a missing man. His name was Guido Bruckheller and he had an Austrian name but was an Italian zoologist, a Ph.D. from Bolzano originally, I believe. He apparently had done some excellent work on tropical rodents as disease vectors. Out of my line by miles. But he was in the books as a most dangerous Axis agent. The fellow spoke a dozen African languages and was a real bushman to boot. He had been staying in Nairobi, watched carefully, but as a nominal Italian citizen, no more than that, since Mussolini was technically neutral at this time.

"Well, it was the period of the so-called 'phoney war' in France. Poland was dished and we were simply waiting for the onslaught. I was on my way back from a certain job in India when I got orders to side-track to Nairobi and at once. Bruckheller had vanished and supposedly a trained Intelligence man was wanted to follow up and find him.

"I found the local security people dithering all over the map. They had the wind up badly and seemed to feel this chap could start a second Senussi uprising or something unless he was caught up with promptly. Personally, mind you, I thought it all a lot of rubbish. One man is just that, one man, and there had

been no reports of any trouble among the tribes in western Kenya. Still, the fellow had vanished and he was supposed to be hot stuff. The locals could have handled it better, I thought.

"There was only one clue as to where he had gone. Two white farmers, out hunting about their farms on the Chania River, thought they'd seen a white man and some natives cross a clearing much higher up the slope at dawn three days earlier. Since the colony was now at war and most of the able-bodied whites were gone, they'd reported it to the local police post at Nyeri, whence it had come in to Headquarters Nairobi. This was absolutely the only report from the whole of Kenya of anyone or anything out of place and so we had to assume it was our lead.

"Since I didn't know the territory, some local talent was needed. What I got was an elderly major of the local volunteer defense force who'd been with Meinertzhagen in Tanganyika during World War I and a middle-aged, one-armed Boer farmer from up north somewhere who said he'd come for the fun of it. Their names were Sizenby and Krock. Krock, the Boer, made very bad jokes, starting with 'I am a young Krock not an English 'old crock,' neen?' We also got six King's African Rifles under a sixty-year-old Kikuyu sergeant named Asoto, who stood five foot six and weighed two hundred pounds, all of it muscle.

"The whole place, I mean Nairobi, was such a hotbed of gossip that half the town must have been in on our mission. One chap buttonholed Sizenby in the Mithaiga Club the night before we left and said, rather incoherently, 'Now do look out, Size. The Kerit is out in the Aberdares. My boys tell me it took four cattle and a grown man last week."

" 'What on earth was that, Major?' I asked Sizenby when we were outside in the street.

" 'Oh, nothing,' he mumbled. 'Lot of fiddle. Supposed to be some animal, quite dangerous up that way, but no one's ever really seen it. Chap was drunk.'

"I stopped still for a moment. You know, I'd never thought of animals at all. We were after a man, who might or might not be dangerous, but there was a largish war on and that was normal. But animals now! 'Look here,' I said, 'what animal is this? Surely not a lion? a leopard? What did that chap say?'

"Sizenby chewed a ratty grey mustache for a bit. He was an undersized creature in an ill-fitting uniform with a vague blue eye. Frankly, he looked pretty hopeless but he and the Boer were all I could get and he was supposed to know the country.

" 'It had several native names,' he said slowly. 'Chimiset is one, Kerit another. Now and again it makes the papers. Then it usually gets called the Nandi Bear.

"The Nandi Bear! Well, you know, even I had heard of that. It was supposed to be the mystery beast of East Africa and made the Sunday supplements regularly along with the Lost Valley of the Nahanni, the Loch Ness monster and supposed living dinosaurs.

" 'That's a lot of hooh-hah, isn't it?' I said. 'I mean really, I thought it was all rot and old settlers' tales. Do you think there is such a creature? I mean actually?'

"He looked at the ground and mumbled again. It was quite obvious he did think there was something to the story, and that he didn't like it at all. I was both intrigued and annoyed. Just then, however, along came the General commanding the Colony forces and I found out he knew all about my mission and had some ideas of his own. In the ensuing, and I may add, pointless, discussion, I quite forgot the Kerit, sometimes called Nandi Bear.

-

"We all left at dawn the next day in an Army truck for Nyeri, our jumping-off point. I was formally introduced to the other ranks, that is the K.A.R. boys and forgot all their names except Sergeant Asoto's at once. Two were Somalis, the rest Kikuyu; that's all I remember, except that they were all good, brave men.

"Now a road of sorts, really a baddish dirt track, barely usable for sturdy vehicles, ran west across the south end of the Aberdare range, going from Nyeri to Naivasha. This we took at once after checking for more news in Nyeri, where there was none. We went up and up in our truck, crashing into pot holes and large rocks until the air actually began to get quite chilly.

" 'Now,' said Krock, reaching me a heavy sweater, 'you see why we bring all this stuff. It gets colder yet, I tell you.' Everyone, including the troops, bundled up, and we all needed it.

"Toward evening, we broke out on to the open plateau, first from the dense rain forest which covered the slopes to about ten thousand feet, and then from a belt of bamboo. Up here, in the light of the setting sun, it looked most unlike my idea of Africa. If I'd had a chance later I'd have traded even for the bamboo.

"Before us stretched a cheerless-looking moor, with here and there an outcropping of rock or a plant like a monstrous cabbage on a stalk, or simply a great vegetable spike, raising its head above the tussocky grass. It was absolutely weird looking and the setting sun made it resemble a patch of Dartmoor crossed with a bad dream. A cold wind blew fitfully across it from the heights above and I shivered.

"The truck ground to a halt. Sizenby and Krock hopped out and began chatting up the local gossip and the Sergeant and his six whirled into galvanized activity. In ten minutes two tents were up, a small one for us three and a large one for them; two fires were crackling and the smell of food and woodsmoke was in the air. I had nothing to do at all, so wandered over to listen absently to Krock and Sizenby, speculating to myself meanwhile on what Bruckheller was doing and why. During a pause in the conversation I interrupted to pose the same question aloud. Perhaps these two might have some fresh ideas, since I had none.

" 'Oh, I know why he's here,' said Sizenby, quite matter-of-fact. 'I knew him, you know; not a bad chap but a bit daft. He's up here because of Egypt.' Just like that! And after I'd been racking my brains for two days!

" 'Now look, Major,' I said, 'what on earth are you talking about?' We had moved to our fire and were standing grouped about it. It was quite dark now, and a white ground mist had formed and lay thick about the camp. There was no moon.

" 'What is this?' I repeated. 'Why haven't you mentioned knowing this man before? No one else in Nairobi seems to have even talked with him.'

" 'Well, you never asked me and it didn't seem important,' he said quietly. 'I rather liked the man. We're both curious chaps and we found some of the same things interesting. At any rate, Bruckheller's quite dotty on the subject of Egyptology. I know he's a zoologist not an archeologist, but like most of us he has a hobby horse. His happens to be ancient Egypt. He was always at me about it. Had I ever seen any Egyptian ruins in these parts, heard of any rock paintings that might be Egyptian looking and so on? For some reason he's convinced that the early Pharaohs went north from around here. He was following his theory down from Ethiopia.'

"I thought for a moment. It all sounded completely mad, but then people's interests frequently are mad. Still it wouldn't wash.

" 'I gather you think that in the middle of a war, knowing that aliens, even neutrals, are subject to arrest for moving in unauthorized areas, this fellow, who is supposed, mind you, to be a trained secret agent, wandered up here to look for Egyptian ruins?'

" 'Yes,' said Sizenby, 'I rather think he did. He was that sort of chap. And I think he'd heard something, d'you see, something that set him off, some recent news from this part of the colony. And perhaps he felt he wouldn't get another chance to see whatever it was.'

"I mulled this over, holding my hands to the fire. The next question was obvious.

" 'Neen,' said Krock, who had simply been listening up to now. 'Nothing new comes from here in the last year, I tell you. I hear all the news, Man, you bet. Only the—,' his voice lowered and he looked over his shoulder at the group of K.A.R. around the other fire, 'the Gadet, the Kerit being out up here, that's new.'

"Sizenby looked at me attentively, but I remembered the conversation outside the Mithaiga Club with no trouble.

" 'I doubt the Nandi Bear, or ancient Egypt either, has much to do with this,' I said sourly. 'Obviously the man received certain orders and followed them. All this bumph and Egypt and—'

" 'Better lower your voice, Captain,' Sizenby cut in, speaking softly. 'The men don't like to

hear about the Kerit, and there's no point in upsetting them needlessly.'

" 'Yah, that's so,' chimed in the Boer. 'We don't talk about it around them.'

"The one-armed South African and the little settler were oddly impressive up here in the cold mountain air. Sizenby had lost the vagueness I'd noted earlier and seemed both tougher and more self-assured. He was telling me to shut up in a very firm way and I got quite irritated.

" 'What on earth is all this?' I said heatedly. 'You two can't really expect me to believe in all this hogwash—mystery animals and Egyptian ruins? Suppose you simply tell me how to find the chap and leave the abstruse speculation to me, eh?"

"Sizenby stared at me a minute and then called over to the other fire. 'Sergeant Asoto, come over here a moment, will you?'

"In a second, Asoto's squat, immaculately-uniformed bulk stood immobile before us, hand at the rigid salute. Sizenby and I returned it, Krock being a 'civvie.'

" 'Sergeant,' said Sizenby slowly, 'the Ingrezi captain thinks we're having a bit of fun with him. I want you to tell him about the Kerit. I know you and your men all know it's out again. Say nothing to the men about my asking this, but simply tell everything you know.'