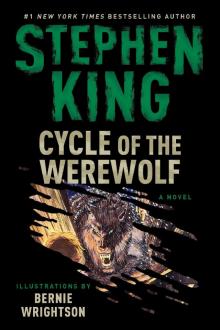

Cycle of the Werewolf

Stephen King

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

In memory of Davis Grubb, and all the voices of Glory.

In the stinking darkness under the barn, he raised his shaggy head. His yellow, stupid eyes gleamed. “I hunger,” he whispered.

Henry Ellender

The Wolf

“Thirty days hath September

April, June, and November,

all the rest but the Second have thirty-one,

Rain and snow and jolly sun,

and the moon grows fat in every one.”

Child’s rime

Somewhere, high above, the moon shines down, fat and full—but here, in Tarker’s Mills, a January blizzard has choked the sky with snow. The wind rams full force down a deserted Center Avenue; the orange town plows have given up long since.

Arnie Westrum, flagman on the GS&WM Railroad, has been caught in the small tool-and-signal shack nine miles out of town; with his small, gasoline-powered rail-rider blocked by drifts, he is waiting out the storm there, playing Last Man Out solitaire with a pack of greasy Bicycle cards. Outside the wind rises to a shrill scream. Westrum raises his head uneasily, and then looks back down at his game again. It is only the wind, after all . . .

But the wind doesn’t scratch at doors . . . and whine to be let in.

He gets up, a tall, lanky man in a wool jacket and railroad coveralls, a Camel cigarette jutting from one corner of his mouth, his seamed New England face lit in soft orange tones by the kerosene lantern which hangs on the wall.

The scratching comes again. Someone’s dog, he thinks, lost and wanting to be let in. That’s all it is . . . but still, he pauses. It would be inhuman to leave it out there in the cold, he thinks (not that it is much warmer in here; in spite of the battery-powered heater, he can see the cold cloud of his breath)—but still he hesitates. A cold finger of fear is probing just below his heart. This has been a bad season in Tarker’s Mills; there have been omens of evil on the land. Arnie has his father’s Welsh blood strong in his veins, and he doesn’t like the feel of things.

Before he can decide what to do about his visitor, the low-pitched whining rises to a snarl. There is a thud as something incredibly heavy hits the door . . . draws back . . . hits again. The door trembles in its frame, and a puff of snow billows in from the top.

Arnie Westrum stares around, looking for something to shore it up with, but before he can do more than reach for the flimsy chair he has been sitting in, the snarling thing strikes the door again with incredible force, splintering it from top to bottom.

It holds for a moment longer, bowed in on a vertical line, and lodged in it, kicking and lunging, its snout wrinkled back in a snarl, its yellow eyes blazing, is the biggest wolf Arnie has ever seen . . .

And its snarls sound terribly like human words.

The door splinters, groans, gives. In a moment the thing will be inside.

In the corner, amongst a welter of tools, a pick leans against the wall. Arnie lunges for it and seizes it as the wolf thrusts its way inside and crouches, its yellow eyes gleaming at the cornered man. Its ears are flattened back, furry triangles. Its tongue lolls. Behind it, snow gusts in through a door that has been shattered down the center.

It springs with a snarl, and Arnie Westrum swings the pick.

Once.

Outside, the feeble lamplight shines raggedly on the snow through the splintered door.

The wind whoops and howls.

The screams begin.

Something inhuman has come to Tarker’s Mills, as unseen as the full moon riding the night sky high above. It is the Werewolf, and there is no more reason for its coming now than there would be for the arrival of cancer, or a psychotic with murder on his mind, or a killer tornado. Its time is now, its place is here, in this little Maine town where baked bean church suppers are a weekly event, where small boys and girls still bring apples to their teachers, where the Nature Outings of the Senior Citizens’ Club are religiously reported in the weekly paper. Next week there will be news of a darker variety.

Outside, its tracks begin to fill up with snow, and the shriek of the wind seems savage with pleasure. There is nothing of God or Light in that heartless sound—it is all black winter and dark ice.

The cycle of the Werewolf has begun.

Love, Stella Randolph thinks, lying in her narrow virgin’s bed, and through her window streams the cold blue light of a St. Valentine’s Day full moon.

Oh love love love, love would be like—

This year Stella Randolph, who runs the Tarker’s Mills Set ’n Sew, has received twenty Valentines—one from Paul Newman, one from Robert Redford, one from John Travolta . . . even one from Ace Frehley of the rock group Kiss. They stand open on the bureau across the room from her, illuminated in the moon’s cold blue light. She sent them all to herself, this year as every year.

Love would be like a kiss at dawn . . . or the last kiss, the real one, at the end of the Harlequin romance stories . . . love would be like roses in twilight . . .

They laugh at her in Tarker’s Mills, yes, you bet. Small boys joke and snigger at her from behind their hands (and sometimes, if they are safe across the street and Constable Neary isn’t around, they will chant Fatty-Fatty-Two-By-Four in their sweet, high mocking sopranos), but she knows about love, and about the moon. Her store is failing by inches, and she weighs too much, but now, on this night of dreams with the moon a bitter blue flood through frost-traced windows, it seems to her that love is still a possibility, love and the scent of summer as he comes . . .

Love would be like the rough feel of a man’s cheek, that rub and scratch—

And suddenly there is a scratching at the window.

She starts up on her elbows, the coverlet falling away from her ample bosom. The moonlight has been blocked out by a dark shape—amorphous but clearly masculine, and she thinks: I am dreaming . . . and in my dreams, I will let him come . . . in my dreams I will let myself come. They use the word dirty, but the word is clean, the word is right; love would be like coming.

She rises, convinced that this is a dream, because there is a man crouched out there, a man she knows, a man she passes on the street nearly everyday. It is—

(love love is coming, love has come)

But as her pudgy fingers fall on the cold sash of the window she sees it is not a man at all; it is an animal out there, a huge, shaggy wolf, his forepaws on the outer sill, his rear legs buried up to the haunches in the snowdrift that crouches against the west side of her house, here on the outskirts of town.

But it’s Valentine’s day and there will be love, she thinks; her eyes have deceived her even in her dream. It is a man, that man, and he is so wickedly handsome.

(wickedness yes love would be like wickedness)

and he has come this moon-decked night and he will take her. He will—

She throws the window up and it is the blast of cold air billowing her filmy blue nightgown out behind that tells her that this is no dream. The man is gone and with a sensation like swooning she realizes he was never there. She takes a shuddering, groping step backward and the wolf leaps smoothly into her room and shakes itself, spraying a dreamy sugarpuff of snow in the darkness.

But love! Love is like . . . is like . . . l

ike a scream—

Too late she remembers Arnie Westrum, torn apart in the railroad shack to the west of town only a month before. Too late . . .

The wolf pads toward her, yellow eyes gleaming with cool lust. Stella Randolph backs slowly toward her narrow virgin’s bed until the back of her pudgy knees strike the frame and she collapses upon it.

Moonlight parts the beast’s shaggy fur in a silvery streak.

On the bureau the Valentine cards shiver minutely in the breeze from the open window; one of them falls and seesaws lazily to the floor, cutting the air in big silent arcs.

The wolf puts its paw up on the bed, one on either side of her, and she can smell its breath . . . hot, but somehow not unpleasant. Its yellow eyes stare into her.

“Lover,” she whispers, and closes her eyes.

It falls upon her.

Love is like dying.

The last real blizzard of the year—heavy, wet snow turning to sleet as dusk comes on and the night closes in—has brought branches tumbling down all over Tarker’s Mills with the heavy gunshot cracks of rotted wood. Mother Nature’s pruning out her deadwood, Milt Sturmfuller, the town librarian, tells his wife over coffee. He is a thin man with a narrow head and pale blue eyes, and he has kept his pretty, silent wife in a bondage of terror for twelve years now. There are a few who suspect the truth—Constable Neary’s wife Joan is one—but the town can be a dark place, and no one knows for sure but them. The town keeps its secrets.

Milt likes his phrase so well that he says it again: Yep, Mother Nature is pruning her deadwood . . . and then the lights go out and Donna Lee Sturmfuller utters a gasping little scream. She also spills her coffee.

You clean that up, her husband says coldly. You clean that up right . . . now.

Yes, honey. Okay.

In the dark, she fumbles for a dishtowel with which to clean up the spilled coffee and barks her shin on a footstool. She cries out. In the dark, her husband laughs heartily. He finds his wife’s pain more amusing than anything, except maybe the jokes they have in Reader’s Digest. Those jokes—Humor in Uniform, Life in These United States—really tickle his funny-bone.

As well as deadwood, Mother Nature has pruned a few powerlines out by Tarker Brook this wild March night; the sleet has coated the big lines, growing heavier and heavier, until they have parted and fallen on the road like a nest of snakes, lazily turning and spitting blue fire.

All of Tarker’s Mills goes dark.

As if finally satisfied, the storm begins to slack off, and not long before midnight the temperature has plummeted from thirty-three degrees to sixteen. Slush freezes solid in weird sculptures. Old Man Hague’s hayfield—known locally as Forty Acre Field—takes on a cracked glaze look. The houses remain dark; oil furnaces tick and cool. No linesman is yet able to get up the skating-rink roads.

The clouds pull apart. A full moon slips in and out between the remnants. The ice coating Main Street glows like dead bone.

In the night, something begins to howl.

Later, no one will be able to say where the sound came from; it was everywhere and nowhere as the full moon painted the darkened houses of the village, everywhere and nowhere as the March wind began to rise and moan like a dead Berserker winding his horn, it drifted on the wind, lonely and savage.

Donna Lee hears it as her unpleasant husband sleeps the sleep of the just beside her; Constable Neary hears it as he stands at the bedroom window of his Laurel Street apartment in his longhandles; Ollie Parker, the fat and ineffectual grammar school principal hears it in his own bedroom; others hear it, as well. One of them is a boy in a wheelchair.

No one sees it. And no one knows the name of the drifter the linesman found the next morning when he finally got out by Tarker Brook to repair the downed cables. The drifter was coated with ice, head cocked back in a silent scream, ragged old coat and shirt beneath chewed open. The drifter sat in a frozen pool of his own blood, staring at the downed lines, his hands still held up in a warding-off gesture with ice between the fingers.

And all around him are pawprints.

Wolfprints.

By the middle of the month, the last of the snow flurries have turned to showers of rain and something amazing is happening in Tarker’s Mills: it is starting to green up. The ice in Matty Tellingham’s cow-pond has gone out, and the patches of snow in the tract of forest called the Big Woods have all begun to shrink. It seems that the old and wonderful trick is going to happen again. Spring is going to come.

The townsfolk celebrate it in small ways in spite of the shadow that has fallen over the town. Gramma Hague bakes pies and sets them out on the kitchen windowsill to cool. On Sunday, at the Grace Baptist Church, the Reverend Lester Lowe reads from The Song of Solomon and preaches a sermon titled “The Spring of the Lord’s Love.” On a more secular note, Chris Wrightson, the biggest drunk in Tarker’s Mills, throws his Great Spring Drunk and staggers off in the silvery, unreal light of a nearly full April moon. Billy Robertson, bartender and proprietor of The Pub, Tarker’s Mills’ only saloon, watches him go and mutters to the barmaid, “If that wolf takes someone tonight, I guess it’ll be Chris.”

“Don’t talk about it,” the barmaid replies, shuddering. Her name is Elise Fournier, she is twenty-four, and she attends the Grace Baptist and sings in the choir because she has a crush on the Rev. Lowe. But she plans to leave the Mills by summer; crush or no crush, this wolf business has begun to scare her. She has begun to think that the tips might be better in Portsmouth . . . and the only wolves there wore sailors’ uniforms.

Nights in Tarker’s Mills as the moon grows fat for the third time that year are uncomfortable times . . . the days are better. On the town common, there is suddenly a skyful of kites each afternoon.

Brady Kincaid, eleven years old, has gotten a Vulture for his birthday and has lost all track of time in his pleasure at feeling the kite tug in his hands like a live thing, watching it dip and swoop through the blue sky above the bandstand. He has forgotten about going home for supper, he is unaware that the other kite-fliers have left one by one, with their box-kites and tent-kites and Aluminum Fliers tucked securely under their arms, unaware that he is alone.

It is the fading daylight and advancing blue shadows which finally make him realize he has lingered too long—that, and the moon just rising over the woods at the edge of the park. For the first time it is a warm-weather moon, bloated and orange instead of a cold white, but Brady doesn’t notice this; he is only aware that he has stayed too long, his father is probably going to whup him . . . and dark is coming.

At school, he has laughed at his schoolmates’ fanciful tales of the werewolf they say killed the drifter last month, Stella Randolph the month before, Arnie Westrum the month before that. But he doesn’t laugh now. As the moon turns April dusk into a bloody furnace-glow, the stories seem all too real.

He begins to wind twine onto his ball as fast as he can, dragging the Vulture with its two bloodshot eyes out of the darkening sky. He brings it in too fast, and the breeze suddenly dies. As a result, the kite dives behind the bandstand.

He starts toward it, winding up string as he goes, glancing nervously back over his shoulder . . . and suddenly the string begins to twitch and move in his hands, sawing back and forth. It reminds him of the way his fishing pole feels when he’s hooked a big one in Tarker’s Stream, above the Mills. He looks at it, frowning, and the line goes slack.

A shattering roar suddenly fills the night and Brady Kincaid screams. He believes now, Yes, he believes now, all right, but it’s too late and his scream is lost under that snarling roar that rises in a sudden, chilling glissade to a howl.

The wolf is running toward him, running on two legs, its shaggy pelt painted orange with moonfire, its eyes glaring green lamps, and in one paw—a paw with human fingers and claws where the nails should be—is Brady’s Vulture kite. It is fluttering madly.

Brady turns to run and dry arms suddenly encircle him; he can smell something like blood and c

innamon, and he is found the next day propped against the War Memorial, headless and disembowelled, the Vulture kite in one stiffening hand.

The kite flutters, as if trying for the sky, as the search-party turn away, horrified and sick. It flutters because the breeze has already come up. It flutters as if it knows this will be a good day for kites.

On the night before Homecoming Sunday at the Grace Baptist Church, the Reverend Lester Lowe has a terrible dream from which he awakes, trembling, bathed in sweat, staring at the narrow windows of the parsonage. Through them, across the road, he can see his church. Moonlight falls through the parsonage’s bedroom windows in still silver beams, and for one moment he fully expects to see the werewolf the old codgers have all been whispering about. Then he closes his eyes, begging for forgiveness for his superstitious lapse, finishing his prayer by whispering the “For Jesus’ sake, amen”—so his mother taught him to end all his prayers.

Ah, but the dream . . .

In his dream it was tomorrow and he had been preaching the Homecoming Sermon. The church is always filled on Homecoming Sunday (only the oldest of the old codgers still call it Old Home Sunday now), and instead of looking out on pews half or wholly empty as he does on most Sundays, every bench is full.

In his dream he has been preaching with a fire and a force that he rarely attains in reality (he tends to drone, which may be one reason that Grace Baptist’s attendance has fallen off so drastically in the last ten years or so). This morning his tongue seems to have been touched with the Pentecostal Fire, and he realizes that he is preaching the greatest sermon of his life, and its subject is this: THE BEAST WALKS AMONG US. Over and over he hammers at the point, vaguely aware that his voice has grown roughly strong, that his words have attained an almost poetic rhythm.