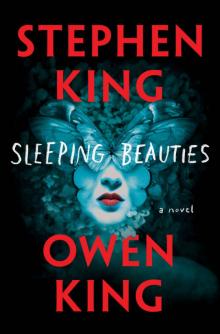

Sleeping Beauties: A Novel

Stephen King

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

In Remembrance of Sandra Bland

It makes no difference if you’re rich or poor

Or if you’re smart or dumb.

A woman’s place in this old world

Is under some man’s thumb,

And if you’re born a woman

You’re born to be hurt.

You’re born to be stepped on,

Lied to,

Cheated on,

And treated like dirt.

—Sandy Posey, “Born a Woman” Lyrics by Martha Sharp

I say you can’t not be bothered by a square of light!

—Reese Marie Dempster, Inmate #4602597-2 Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.

—Sen. Addison “Mitch” McConnell, speaking of Sen. Elizabeth Warren

CHARACTERS

TOWN OF DOOLING, SEAT OF DOOLING COUNTY

• Truman “Trume” Mayweather, 26, a meth cook

• Tiffany Jones, 28, Truman’s cousin

• Linny Mars, 40, dispatcher, Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Sheriff Lila Norcross, 45, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Jared Norcross, 16, a junior at Dooling High School, son of Lila and Clint

• Anton Dubcek, 26, owner and operator of Anton the Pool Guy, LLC

• Magda Dubcek, 56, Anton’s mother

• Frank Geary, 38, animal control officer, Town of Dooling

• Elaine Geary, 35, a Goodwill volunteer and Frank’s spouse

• Nana Geary, 12, a sixth grader at Dooling Middle School

• Old Essie, 60, a homeless woman

• Terry Coombs, 45, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Rita Coombs, 42, Terry’s spouse

• Roger Elway, 28, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Jessica Elway, 28, Roger’s spouse

• Platinum Elway, 8 months old, daughter of Roger and Jessica

• Reed Barrows, 31, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Leanne Barrows, 32, Reed’s spouse

• Gary Barrows, 2, son of Reed and Leanne

• Drew T. Barry, 42, of Drew T. Barry Indemnity

• Vern Rangle, 48, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Elmore Pearl, 38, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Rupe Wittstock, 26, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Will Wittstock, 27, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Dan “Treater” Treat, 27, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department

• Jack Albertson, 61, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department (ret.)

• Mick Napolitano, 58, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department (ret.)

• Nate McGee, 60, of the Dooling Sheriff’s Department (ret.)

• Carson “Country Strong” Struthers, 32, an ex–Golden Gloves boxer

• Coach JT Wittstock, 64, Dooling High School Warriors varsity football team

• Dr. Garth Flickinger, 52, a plastic surgeon

• Fritz Meshaum, 37, a mechanic

• Barry Holden, 47, a public defender

• Oscar Silver, 83, a judge

• Mary Pak, 16, a junior at Dooling High School

• Eric Blass, 17, a senior at Dooling High School

• Curt McLeod, 17, a senior at Dooling High School

• Kent Daley, 17, a senior at Dooling High School

• Willy Burke, 75, a volunteer

• Dorothy Harper, 80, retired

• Margaret O’Donnell, 72, sister of Gail, retired

• Gail Collins, 68, sister of Margaret, a secretary at a dentist’s office

• Mrs. Ransom, 77, a baker

• Molly Ransom, 10, the granddaughter of Mrs. Ransom

• Johnny Lee Kronsky, 41, a private investigator

• Jaime Howland, 44, a history professor

• Eve Black, appearing about 30 years of age, a stranger

THE PRISON

• Janice Coates, 57, Warden, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Lawrence “Lore” Hicks, 50, Vice-Warden, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Rand Quigley, 30, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Vanessa Lampley, 42, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women, and 2010 & 2011 Ohio Valley Arm-Wrestling Champion, 35–45 Age Group

• Millie Olson, 29, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Don Peters, 35, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Tig Murphy, 45, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Billy Wettermore, 23, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Scott Hughes, 19, Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Blanche McIntyre, 65, Secretary, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Dr. Clinton Norcross, 48, Senior Psychiatric Officer, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women, and Lila’s spouse

• Jeanette Sorley, 36, Inmate #4582511-1, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Ree Dempster, 24, Inmate #4602597-2, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Kitty McDavid, 29, Inmate #4603241-2, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Angel Fitzroy, 27, Inmate #4601959-3, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Maura Dunbarton, 64, Inmate #4028200-1, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Kayleigh Rawlings, 40, Inmate #4521131-2, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Nell Seeger, 37, Inmate #4609198-1, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Celia Frode, 30, Inmate #4633978-2, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

• Claudia “the Dynamite Body-a” Stephenson, 38, Inmate #4659873-1, Dooling Correctional Facility for Women

OTHERS

• Lowell “Little Low” Griner, 35, an outlaw

• Maynard Griner, 35, an outlaw

• Michaela Morgan nee Coates, 26, National Reporter, NewsAmerica

• Kinsman Brightleaf (Scott David Winstead Jr.), 60, Pastor-General, the Bright Ones

• A common fox, between 4 and 6 years of age

SLEEPING BEAUTIES

The moth makes Evie laugh. It lands on her bare forearm and she brushes her index finger lightly across the brown and gray waves that color its wings. “Hello, gorgeous,” she tells the moth. It lifts away. Upward, upward, and upward the moth goes, and is swallowed by a slice of the sun tangled amid the glossy green leaves twenty feet above Evie’s place among the roots on the ground.

A coppery red rope leaks from a black socket at the center of the trunk and twists between plates of bark. Evie doesn’t trust the snake, obviously. She’s had trouble with him before.

Her moth and ten thousand others surge from the treetop in a crackling, dun-colored cloud. The swarm rolls across the sky in the direction of the sickly second-growth pines on the other side of the meadow. She rises to follow. Stalks crunch under her steps and the waist-high grass scrapes her bare skin. As she approaches the sad, mostly logged-over wood, she detects the first chemical smells—ammonia, benzene, petroleum, so many other

s, ten thousand nicks on a single patch of flesh—and relinquishes the hope she had not realized she harbored.

Webs spill from her footprints and sparkle in the morning light.

PART ONE

THE AULD TRIANGLE

In the female prison

There are seventy women

I wish it was with them that I did dwell,

Then that old triangle

Could jingle jangle

Along the banks of the Royal Canal.

—Brendan Behan

CHAPTER 1

1

Ree asked Jeanette if she ever watched the square of light from the window. Jeanette said she didn’t. Ree was in the top bunk, Jeanette in the bottom. They were both waiting for the cells to unlock for breakfast. It was another morning.

It seemed that Jeanette’s cellmate had made a study of the square. Ree explained that the square started on the wall opposite the window, slid down, down, down, then slopped over the surface of their desk, and finally made it out onto the floor. As Jeanette could now see, it was right there in the middle of the floor, bright as anything.

“Ree,” Jeanette said. “I just can’t be bothered with a square of light.”

“I say you can’t not be bothered by a square of light!” Ree made the honking noise that was how she expressed amusement.

Jeanette said, “Okay. Whatever the fuck that means,” and her cellmate just honked some more.

Ree was okay, but she was like a toddler, how silence made her anxious. Ree was in for credit fraud, forgery, and drug possession with intent to sell. She hadn’t been much good at any of them, which had brought her here.

Jeanette was in for manslaughter; on a winter night in 2005 she had stabbed her husband, Damian, in the groin with a clutchhead screwdriver and because he was high he’d just sat in an armchair and let himself bleed to death. She had been high, too, of course.

“I was watching the clock,” Ree said. “Timed it. Twenty-two minutes for the light to move from the window to there on the floor.”

“You should call Guinness,” said Jeanette.

“Last night I had a dream about eating chocolate cake with Michelle Obama and she was pissed: ‘That’s going to make you fat, Ree!’ But she was eating the cake, too.” Ree honked. “Nah. I didn’t. Made that up. Actually I dreamed about this teacher I had. She kept telling me I wasn’t in the right classroom, and I kept telling her I was in the right classroom, and she’d say okay, and then teach some, and tell me I wasn’t in the right room, and I’d say no, I was in the right room, and we went around like that. It was more exasperating than anything. What’d you dream, Jeanette?”

“Ah . . .” Jeanette tried to remember, but she couldn’t. Her new medication seemed to have thickened her sleep. Before, sometimes she had nightmares about Damian. He’d usually look the way he did the morning after, when he was dead, his skin that streaky blue, like wet ink.

Jeanette had asked Dr. Norcross if he thought the dreams had to do with guilt. The doctor squinted at her in that are-you-fucking-serious way that used to drive her nuts but that she had come around on, and then he had asked her if she was of the opinion that bunnies had floppy ears. Yeah, okay. Got it. Anyhow, Jeanette didn’t miss those dreams.

“Sorry, Ree. I got nothing. Whatever I dreamed, it’s gone.”

Somewhere out in the second-floor hall of B Wing, shoes were clapping along the cement: an officer making some last minute check before the doors opened.

Jeanette closed her eyes. She made up a dream. In it, the prison was a ruin. Lush vines climbed the ancient cell walls and sifted in the spring breeze. The ceiling was half-gone, gnawed away by time so that only an overhang remained. A couple of tiny lizards ran over a pile of rusty debris. Butterflies tumbled in the air. Rich scents of earth and leaf spiced what remained of the cell. Bobby was impressed, standing beside her at a hole in the wall, looking in. His mom was an archeologist. She’d discovered this place.

“You think you can be on a game show if you have a criminal record?”

The vision collapsed. Jeanette moaned. Well, it had been nice while it lasted. Life was definitely better on the pills. There was a calm, easy place she could find. Give the doc his due; better living through chemistry. Jeanette reopened her eyes.

Ree was goggling at Jeanette. Prison didn’t have much to say for it, but a girl like Ree, maybe she was safer inside. Out in the world, she’d just as likely walk into traffic. Or sell dope to a narc who looked like nothing but a narc. Which she had done.

“What’s wrong?” Ree asked.

“Nothing. I was just in paradise, that’s all, and your big mouth blew it up.”

“What?”

“Never mind. Listen, I think there should be a game show where you can only play if you do have a criminal record. We could call it Lying for Prizes.”

“I like that a lot! How would it work?”

Jeanette sat up and yawned, shrugged. “I’ll have to think about it. You know, work out the rules.”

Their house was as it always had been and always would be, world without end, amen. A cell ten steps long, with four steps between the bunks and the door. The walls were smooth, oatmeal-colored cement. Their curling snapshots and postcards were held (little that anyone cared to look) with blobs of green sticky-tack in the single approved space. There was a small metal desk set against one wall and a short metal shelving unit set against the opposite wall. To the left of the door was the steel toilet where they had to squat, each looking away to lend a poor illusion of privacy. The cell door, its double-paned window at eye level, gave a view of the short corridor that ran through B Wing. Every inch and object within the cell were sauced in the pervasive odors of prison: sweat, mildew, Lysol.

Against her will, Jeanette finally took note of the sun square between the beds. It was almost to the door—but it wouldn’t get any farther, would it? Unless a screw put a key in the lock or opened the cell from the Booth, it was trapped in here just as they were.

“And who would host?” Ree asked. “Every game show needs a host. Also, what kind of prizes? The prizes have to be good. Details! We gotta figure out all the details, Jeanette.”

Ree had her head propped up and was winding a finger around in her tight bleached curls as she looked at Jeanette. Near the top of Ree’s forehead there was a patch of scar tissue that resembled a grill mark, three deep parallel lines. Although Jeanette didn’t know what had caused the scar, she could guess who had made it: a man. Maybe her father, maybe her brother, maybe a boyfriend, maybe a guy she’d never seen before and never would see again. Among the inmates of Dooling Correctional there was, to put it lightly, very little history of prize-winning. Lots of history with bad guys, though.

What could you do? You could feel sorry for yourself. You could hate yourself or you could hate everyone. You could get high sniffing cleaning products. You could do whatever you wanted (within your admittedly limited options), but the situation wouldn’t change. Your next turn to spin the great big shiny Wheel of Fortune would arrive no sooner than your next parole hearing. Jeanette wanted to put as much arm as she could into hers. She had her son to think about.

There was a resounding thud as the officer in the Booth opened sixty-two locks. It was 6:30 AM, everyone out of their cells for head-count.

“I don’t know, Ree. You think about it,” Jeanette said, “and I’ll think about it, and then we’ll exchange notes later.” She swung her legs out of bed and stood.

2

A few miles from the prison, on the deck of the Norcross home, Anton the pool guy was skimming for dead bugs. The pool had been Dr. Clinton Norcross’s tenth anniversary present to his wife, Lila. The sight of Anton often made Clint question the wisdom of this gift. This morning was one of those times.

Anton was shirtless, and for two good reasons. First, it was going to be a hot day. Second, his abdomen was a rock. He was ripped, was Anton the pool guy; he looked like a stud on the cover of a romance novel. If you shot

bullets at Anton’s abdomen, you’d want to do it from an angle, in case of a ricochet. What did he eat? Mountains of pure protein? What was his workout? Cleaning the Augean Stables?

Anton glanced up, smiling from under the shimmering panes of his Wayfarers. With his free hand he waved at Clint, who was watching from the second-floor window of the master bathroom.

“Jesus Christ, man,” Clint said quietly to himself. He waved back. “Have a heart.”

Clint sidled away from the window. In the mirror on the closed bathroom door there appeared a forty-eight-year-old white male, BA from Cornell, MD from NYU, modest love handles from Starbucks Grande Mochas. His salt and pepper beard was less woodcutter-virile, more lumpen one-legged sea captain.

That his age and softening body should come as any kind of a surprise struck Clint as ironic. He had never had much patience with male vanity, especially the middle-aged variety, and cumulative professional experience had, if anything, trimmed that particular fuse even shorter. In fact, what Clint thought of as the great turning point of his medical career had occurred eighteen years earlier, in 1999, when a prospective patient named Paul Montpelier had come to the young doctor with a “crisis of sexual ambition.”

He had asked Montpelier, “When you say ‘sexual ambition,’ what do you mean?” Ambitious people sought promotions. You couldn’t really become vice-president of sex. It was a peculiar euphemism.

“I mean . . .” Montpelier appeared to weigh various descriptors. He cleared his throat and settled on, “I still want to do it. I still want to go for it.”

Clint said, “That doesn’t seem unusually ambitious. It seems normal.”

Fresh from his psych residency, and not yet softening, this was only Clint’s second day in the office and Montpelier was just his second patient.

(His first patient had been a teenager with some anxieties about her college applications. Pretty quickly, however, it had emerged that the girl had received a 1570 on her SATs. Clint pointed out that this was excellent, and there had been no need for treatment or a second appointment. Cured! he had dashed off on the bottom of the yellow legal pad he used to take notes on.)