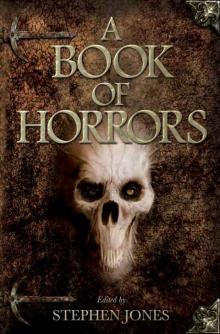

A Book of Horrors

Stephen King

A BOOK OF

HORRORS

A

BOOK

of

HORRORS

Edited by

STEPHEN JONES

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Quercus

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London

W1U 8EW

Selection and editorial material copyright © Stephen Jones 2011

‘The Little Green God of Agony’ copyright © Stephen King 2011;

‘Charcloth, Firesteel and Flint’ copyright © Caitlín R. Kiernan 2011;

‘Ghosts With Teeth’ copyright © Peter Crowther 2011;

‘The Coffin-Maker’s Daughter’ copyright © Angela Slatter 2011;

‘Roots and All’ copyright © Brian Hodge 2011;

‘Tell Me I’ll See You Again’ copyright © Dennis Etchison 2011;

‘The Music of Bengt Karlsson, Murderer’ copyright © John Ajvide Lindqvist 2011,

English translation copyright © 2011 by Marlaine Delargy;

‘Getting it Wrong’ copyright © Ramsey Campbell 2011;

‘Alice Through the Plastic Sheet’ copyright © Robert Shearman 2011;

‘The Man in the Ditch’ copyright © Lisa Tuttle 2011;

‘A Child’s Problem’ copyright © Reggie Oliver 2011;

‘Sad, Dark Thing’ copyright © Michael Marshall Smith 2011;

‘Near Zennor’ copyright © Elizabeth Hand 2011;

‘Last Words’ copyright © Richard Christian Matheson 2011

The moral right of Stephen Jones to be

identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85738 808 7 (HB)

ISBN 978 0 85738 809 4 (TPB)

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters,

businesses, organisations, places and events are

either the product of the author’s imagination

or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or

locales is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Ellipsis Digital Limited, Glasgow

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For

Ramsey Campbell

Dennis Etchison

Charles L. Grant

David A. Sutton

and

Karl Edward Wagner,

for teaching me how to do the best job in the world.

Contents

Introduction

Whatever Happened to Horror?

Stephen Jones

The Little Green God of Agony

Stephen King

Charcloth, Firesteel and Flint

Caitlín R. Kiernan

Ghosts with Teeth

Peter Crowther

The Coffin-Maker’s Daughter

Angela Slatter

Roots and All

Brian Hodge

Tell Me I’ll See You Again

Dennis Etchison

The Music of Bengt Karlsson, Murderer

John Ajvide Lindqvist

Getting it Wrong

Ramsey Campbell

Alice Through the Plastic Sheet

Robert Shearman

The Man in the Ditch

Lisa Tuttle

A Child’s Problem

Reggie Oliver

Sad, Dark Thing

Michael Marshall Smith

Near Zennor

Elizabeth Hand

Last Words

Richard Christian Matheson

Introduction

Whatever Happened to Horror?

WHAT THE HELL happened to the horror genre? Whatever happened to menacing monsters, vicious vampires, lethal lycanthropes, ghastly ghosts and monstrous mummies?

These days our bloodsuckers are more likely to show their romantic nature, werewolves work for covert government organisations, phantoms are private investigators and the walking dead can be found sipping tea amongst the polite society of a Jane Austen novel.

These are not the iconic figures of fear and wonder that we grew up with. These are not the Creatures of the Night that have scared multiple generations over the centuries and forced countless small children to hide under the bedclothes reading their books and comics by torchlight.

Today we are living in a world that is ‘horror-lite’. This appalling appellation was coined by publishers to describe the type of fiction that is currently enjoying massive success under such genre categories as ‘paranormal romance’, ‘urban fantasy’, ‘literary mash-up’ or even ‘steampunk’.

Although it cannot be denied that there is an audience for these types of fictions, for the most part these books are not aimed at readers of traditional horror stories. The audience for this type of fiction has no interest in being deliciously scared by what they read, or left thinking about a particularly disturbing tale long after they have finished a story and closed the book. And that would not be a problem if publishers and booksellers were not usurping the traditional horror market with an avalanche of disposable volumes aimed at the middle-of-the-road reader.

Well, the time has come to reclaim the horror genre for those who understand and appreciate the worth and impact of a scary story.

With A Book of Horrors we hope that we have lived up to that title and all that it implies.

As anybody who has ever read any of my other books knows, my own definition of what makes a superior horror story is pretty inclusive. Obviously not every tale is going to appeal to every reader, but what I have attempted to do is bring you a wide range of original stories, by some of the finest writers working in the field today, that explore the many monstrous facets of the genre that we like to call ‘horror’.

That is not to say that there is no room for humour – check out Ramsey Campbell’s grimly gruesome ‘Getting it Wrong’ and Robert Shearman’s unsettling yet hilarious ‘Alice Through the Plastic Sheet’ – and our other horrors range from the more traditional monsters (Stephen King’s ‘The Little Green God of Agony’ and Peter Crowther’s ‘Ghosts with Teeth’) and the classic ghost story (John Ajvide Lindqvist’s ‘The Music of Bengt Karlsson, Murderer’ and Reggie Oliver’s ‘A Child’s Problem’), through the modern supernatural thriller (Lisa Tuttle’s ‘The Man in the Ditch’ and Michael Marshall Smith’s ‘Sad, Dark Thing’) and a pair of very different mythological menaces (Caitlín R. Kiernan’s ‘Charcloth, Firesteel and Flint’ and Brian Hodge’s ‘Roots and All’) to more lyrical and literary tales (Angela Slatter’s ‘The Coffin-Maker’s Daughter’, Dennis Etchison’s ‘Tell Me I’ll See You Again’ and Elizabeth Hand’s remarkable novella ‘Near Zennor’). Finally, we close with Richard Christian Matheson’s disturbingly dark epigram – the appropriately titled ‘Last Words’.

Many of the contributors to this volume are experimenting with form and structure and length to bring the horror story bang up-to-date, while others are working in the age-old practice of presenting their terrors in the most straightforward – and effective – manner possible.

; Whatever your fears, we hope that you will find them within these pages. This is what modern horror fiction is all about and, if you enjoy the stories assembled within these pages, then you can say that you were there when the fight back began.

Welcome to A Book of Horrors – it’s time to let the nightmares begin …

—Stephen Jones

London, England

June 2011

The Little Green God of Agony

—STEPHEN KING—

I WAS IN AN ACCIDENT,’ Newsome said.

Katherine MacDonald, sitting beside the bed and attaching one of the four TENS units to his scrawny thigh just below the basketball shorts he now always wore, did not look up. Her face was carefully blank. She was a piece of human furniture in this big house – in this big bedroom where she now spent most of her working life – and that was the way she liked it. Attracting Mr Newsome’s attention was usually a bad idea, as any of his employees knew. But her thoughts ran on, just the same. Now you tell them that you actually caused the accident. Because you think taking responsibility makes you look like a hero.

‘Actually,’ Newsome said, ‘I caused the accident. Not so tight, Kat, please.’

She could have pointed out, as she did at the start, that the TENS lost their efficacy if they weren’t tight to the outraged nerves they were supposed to soothe, but she was a fast learner. She loosened the Velcro strap a little, thinking: The pilot told you there were thunderstorms in the Omaha area.

‘The pilot told me there were thunderstorms in the area,’ Newsome continued. The two men listened closely. Jensen had heard it all before, of course, but you always listened closely when the man doing the talking was the sixth-richest man not just in America but in the world. Three of the other five mega-rich guys were dark-complected fellows who wore robes and drove places in armoured Mercedes-Benzes.

She thought: But I told him it was imperative that I make that meeting.

‘But I told him it was imperative that I make that meeting,’ Newsome carried on.

The man sitting next to Newsome’s personal assistant was the one who interested her – in an anthropological sort of way. His name was Rideout. He was tall and very thin, maybe sixty, wearing plain grey pants and a white shirt buttoned all the way to his scrawny neck, which was red with overshaving. Kat supposed he’d wanted to get a close one before meeting the sixth-richest man in the world. Beneath his chair was the only item he’d carried into this meeting, a long black lunchbox with a curved top meant to hold a Thermos. A working man’s lunchbox, although what he claimed to be was a minister. So far Rideout hadn’t said a word, but she didn’t need her ears to know what he was. The whiff of charlatan was strong about him. In fifteen years as a nurse specialising in pain patients, she had met her share. At least this one wasn’t wearing any crystals.

Now tell them about your revelation, she thought as she carried her stool around to the other side of the bed. It was on casters, but Newsome didn’t like the sound when she rolled on it. She might have told another patient that carrying the stool wasn’t in her contract, but when you were being paid five thousand dollars a week for what were essentially human caretaking services, you kept your smart remarks to yourself. Nor did you tell the patient that emptying and washing out bedpans wasn’t in your contract. Although lately her silent compliance was wearing a little thin. She felt it happening. Like the fabric of a shirt that had been worn and washed too many times.

Newsome was speaking primarily to the fellow in the farmer-goes-to-town get-up. ‘As I lay on the runway in the rain among the burning pieces of a fourteen-million-dollar aircraft, most of the clothes torn off my body – that’ll happen when you hit pavement and roll fifty or sixty feet – I had a revelation.’

Actually, two of them, Kat thought as she strapped a second TENS unit on his other wasted, flabby, scarred leg.

‘Actually, two of them,’ Newsome said. ‘One was that it was very good to be alive, although I understood – even before the pain that’s been my constant companion for the last two years started to eat through the shock – that I had been badly hurt. The second was that the word imperative is used very loosely by most people, including my former self. There are only two imperative things. One is life itself, the other is freedom from pain. Do you agree, Reverend Rideout?’ And before Rideout could agree (for surely he would do nothing else), Newsome said in his waspy, hectoring, old man’s voice: ‘Not so goddam tight, Kat! How many times do I have to tell you?’

‘Sorry,’ she murmured, and loosened the strap. Why do I even try?

Melissa, the housekeeper, looking trim in a white blouse and high-waisted white slacks, came in with a coffee tray. Jensen accepted a cup, along with two packets of artificial sweetener. The new one, the bottom-of-the-barrel so-called reverend, only shook his head. Maybe he had some kind of holy coffee in his lunchbox Thermos. Kat didn’t get an offer. When she took coffee, she took it in the kitchen with the rest of the help. Or in the summerhouse … only this wasn’t summer. It was November, and wind-driven rain lashed the windows.

‘Shall I turn you on, Mr Newsome, or would you prefer that I leave now?’

She didn’t want to leave. She’d heard the whole story many times before – the imperative meeting, the crash, how Andrew Newsome had been ejected from the burning plane, about the broken bones, chipped spine and dislocated neck, most of all about the twenty-four months of unrelieved suffering, which he would soon get to – and it bored her. But Rideout didn’t. Other charlatans would undoubtedly follow, now that all reputable relief resources had been exhausted, but Rideout was the first, and Kat was interested to see how the farmer-looking fellow would go about separating Andy Newsome from a large chunk of his cash. Or how he would try. Newsome hadn’t amassed his obscene piles of cash by being stupid, but of course he wasn’t the same man he had been, no matter how real his pain might be. On that subject, Kat had her own opinions, but this was the best job she’d ever had. At least in terms of money. And if Newsome wanted to continue suffering, wasn’t that his choice?

‘Go ahead, honey, turn me on.’ He waggled his eyebrows at her. Once the lechery might have been real (Kat thought Melissa might have information on that subject), but now it was just a pair of shaggy eyebrows working on muscle memory.

Kat plugged the cords into the control unit and flicked the switch. Properly attached, the TENS units would have sent a weak electrical current into Newsome’s muscles, a therapy that seemed to have some ameliorative effects … although no one could say exactly why, or if they were entirely of the placebo variety. Be that as it might, they would do nothing for Newsome tonight. Hooked up as loosely as they were, they had been reduced to the equivalent of joy-buzzers. Expensive ones.

‘Shall I—?’

‘Stay!’ he said. ‘Therapy!’

The lord wounded in battle commands, she thought, and I obey.

She bent over to pull her chest of goodies out from under the bed. It was filled with tools many of her past clients referred to as implements of torture. Jensen and Rideout paid no attention to her. They continued to look at Newsome, who might (or might not) have been granted revelations that had changed his priorities and outlook on life, but who still enjoyed holding court.

He told them about awakening in a cage of metal and mesh. There were steel gantries called fixators on both legs and one arm to immobilise joints that had been repaired with ‘about a hundred’ steel pins (actually seventeen; Kat had seen the X-rays). The fixators were anchored in the outraged and splintered femurs, tibiae, fibulae, humerus, radius, ulna. His back was encased in a kind of chain-mail girdle that went from his hips to the nape of his neck. He talked about sleepless nights that seemed to go on not for hours but for years. He talked about the crushing headaches. He told them about how even wiggling his toes caused pain all the way up to his jaw, and the shrieking agony that bit into his legs when the doctors insisted that he move them, fixators and all, so he wouldn’t entirely lose their function. He t

old them about the bedsores, and how he bit back howls of hurt and outrage when the nurses attempted to roll him on his side so the sores could be flushed out.

‘There have been another dozen operations in the last two years,’ he said with a kind of dark pride. Actually, Kat knew, there had been five, two of those to remove the fixators when the bones were sufficiently healed. Unless you included the minor procedure to re-set his broken fingers, that was. Then you could say there were six, but she didn’t consider surgical stuff necessitating no more than local anaesthetic to be ‘operations’. If that were the case she’d had a dozen herself, most of them while listening to Muzak in a dentist’s chair.

Now we get to the false promises, she thought as she placed a gel pad in the crook of Newsome’s right knee and laced her hands together on the hanging hot-water bottles of muscle beneath his right thigh. That comes next.

‘The doctors promised me the pain would abate,’ Newsome said. ‘That in six weeks I’d only need the narcotics before and after my physical therapy sessions with the Queen of Pain here. That I’d be walking again by the summer of 2010. Last summer.’ He paused for effect. ‘Reverend Rideout, those were false promises. I have almost no flexion in my knees at all, and the pain in my hips and back is beyond description. The doctors— Ah! Oh! Stop, Kat, stop!’

She had raised his right leg to a ten-degree angle, perhaps a little more. Not even enough to hold the cushioning pad in place.

‘Let it go down! Let it down, goddammit!’

Kat relaxed her hold on his knee and the leg returned to the hospital bed. Ten degrees. Possibly twelve. Whoop-de-do. Sometimes she got it all the way to fifteen – and the left leg, which was a little better, to twenty degrees of flex – before he started hollering like a kid who sees a hypodermic needle in a school nurse’s hand. The doctors guilty of false promises had not been guilty of false advertising; they had told him the pain was coming. Kat had been there as a silent onlooker during several of those consultations. They had told him he would swim in pain before those crucial tendons, shortened by the accident and frozen in place by the fixators, stretched out and once again became limber. He would have plenty of pain before he was able to get the bend in his knees back to ninety degrees. Before he would be able to sit in a chair or behind the wheel of a car, that was. The same was true of his back and his neck. The road to recovery led through the Land of Pain, that was all.