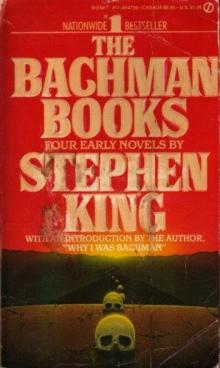

The Bachman Books

Stephen King

The Bachman Books

Stephen King

Richard Bachman

Stephen King

Why I Was Bachman

1

Between 1977 and 1984, I published five novels under the pseudonym of Richard Bachman. These were Rage (1977), The Long Walk (1979), Roadwork (1981), The Running Man (1982), and Thinner (1984). There were two reasons I was finally linked with Bachman: first, because the first four books, all paperback originals, were dedicated to people associated with my life, and second, because my name appeared on the copyright forms of one book. Now people are asking me why I did it, and I don't seem to have any very satisfactory answers. Good thing I didn't murder anyone, isn't it?

2

I can make a few suggestions, but that's all. The only important thing I ever did in my life for a conscious reason was to ask Tabitha Spruce, the college co-ed I was seeing, if she would marry me. The reason was that I was deeply in love with her. The joke is that love itself is an irrational and indefinable emotion.

Sometimes something just says Do this or Don't do that. I almost always obey that voice, and when I disobey it I usually rue the day. All I'm saying is that I've got a hunch-player's approach to life. My wife accuses me of being an impossibly picky Virgo and I guess I am in some ways-I usually know at any given time how many pieces of a 500-piece puzzle I've put in, for instance-but I never really planned anything big that I ever did, and that includes the books I've written. I never sat down and wrote page one with anything but the vaguest idea of how things would come out.

One day it occurred to me that I ought to publish Getting It On, a novel which Doubleday almost published two years before they published Carrie, under a pseudonym. It seemed like a good idea so I did it.

Like I say, good thing I didn't kill anybody, huh?

3

In 1968 or 1969, Paul McCartney said a wistful and startling thing in an interview. He said the Beatles had discussed the idea of going out on the road as a bar-band named Randy and the Rockets. They would wear hokey capes and masks a la Count Five, he said, so no one would recognize them, and they would just have a raveup like in the old days.

When the interviewer suggested they would be recognized by their voices, Paul seemed at first startled . . . and then a bit appalled.

4

Cub Koda, possibly America's greatest houserocker, once told me this story about Elvis Presley, and like the man said, if it ain't true, it oughtta be. Cub said Elvis told an interviewer something that went like this: I was like a cow in a pen with a whole bunch of other cows, only I got out somehow. Well, they came and got me and put me in another pen, only this one was bigger and I had it all to myself. I looked around and seen the fences was so high I'd never get out. So I said, "All right, I'll graze. "

5

I wrote five novels before Carrie. Two of them were bad, one was indifferent, and I thought two of them were pretty good. The two good ones were Getting It On (which became Rage when it was finally published) and The Long Walk. Getting It On was begun in 1966, when I was a senior in high school. I later found it moldering away in an old box in the cellar of the house where I'd grown up-this rediscovery was in 1970, and I finished the novel in 1971. The Long Walk was written in the fall of 1966 and the spring of 1967, when I was a freshman at college.

I submitted Walk to the Bennett Cerf/Random House first-novel competition (which has, I think, long since gone the way of the blue suede shoe) in the fall of 1967 and it was promptly rejected with a form note . . . no comment of any kind. Hurt and depressed, sure that the book must really be terrible, I stuck it into the fabled TRUNK, which all novelists, both published and aspiring, carry around. I never submitted it again until Elaine Geiger at New American Library asked if "Dicky" (as we called him) was going to follow up Rage. The Long Walk went in the TRUNK, but as Bob Dylan says in "Tangled Up in Blue," it never escaped my mind.

None of them has ever escaped my mind-not even the really bad ones.

6

The numbers have gotten very big. That's part of it. I have times when I feel as if I planted a modest packet of words and grew some kind of magic beanstalk . . .or a runaway garden of books (OVER 40 MILLION KING BOOKS IN PRINT!!!, as my publisher likes to trumpet). Or, put it another way-sometimes I feel like Mickey Mouse in Fantasia. I knew enough to get the brooms started, but once they start to march, things are never the same.

Am I bitching? No. At least they're very gentle bitches if I am. I have tried my best to follow that other Dylan's advice and sing in my chains like the sea. I mean, I could get down there in the amen corner and crybaby about how tough it is to be Stephen King, but somehow I don't think all those people out there who are a) unemployed or b) busting heavies every week just to keep even with the house payments and the MasterCharge bill would feel a lot of sympathy for me. Nor would I expect it. I'm still married to the same woman, my kids are healthy and bright, and I'm being well paid for doing something I love. So what's to bitch about?

Nothing.

Almost.

7

Memo to Paul McCartney, if he's there: the interviewer was right. They would have recognized your voices, but before you even opened your mouths, they would have recognized George's guitar licks. I did five books as Randy and the Rockets and I've been getting letters asking me if I was Richard Bachman from the very beginning.

My response to this was simplicity itself: I lied.

8

I think I did it to turn the heat down a little bit; to do something as someone other than Stephen King. I think that all novelists are inveterate role-players and it was fun to be someone else for a while-in this case, Richard Bachman. And he did develop a personality and a history to go along with the bogus author photo on the back of Thinner and the bogus wife (Claudia Inez Bachman) to whom the book is dedicated. Bachman was a fairly unpleasant fellow who was born in New York and spent about ten years in the merchant marine after four years in the Coast Guard. He ultimately settled in rural central New Hampshire, where he wrote at night and tended to his medium-sized dairy farm during the day. The Bachmans had one child, a boy, who died in an unfortunate accident at the age of six (he fell through a well cover and drowned). Three years ago a brain tumor was discovered near the base of Bachman's brain; tricky surgery removed it. And he died suddenly in February of 1985 when the Bangor Daily News, my hometown paper, published the story that I was Bachman-a story which I confirmed. Sometimes it was fun to be Bachman, a curmudgeonly recluse a la J. D. Salinger, who never gave interviews and who, on the author questionnaire from New English Library in London, wrote down "rooster worship" in the blank provided for religion.

I've been asked several times if I did it because I thought I was overpublishing the market as Stephen King. The answer is no. I didn't think I was overpublishing the market . . . but my publishers did. Bachman provided a compromise for both of us. My "Stephen King publishers" were like a frigid wifey who only wants to put out once or twice a year, encouraging her endlessly horny hubby to find a call girl. Bachman was where I went when I had to have relief. This does nothing, however, to explain why I've felt this restless need to publish what I write when I don't need the dough.

I repeat, good thing I didn't kill someone, huh?

10

I've been asked several times if I did it because I feel typecast as a horror writer. The answer is no. I don't give a shit what people call me as long as I can go to sleep at night.

Nevertheless, only the last of the Bachman books is an out-and-out horror story, and the fact hasn't escaped me. Writing something that was not horror as Stephen King would be perfectly easy, but answering the questions about why I did it would be a pain in the ass. When

I wrote straight fiction as Richard Bachman, no one asked the questions. In fact, ha-ha, hardly anyone read the books.

Which leads us to what might be-well, not the reason why that voice spoke up in the first place, but the closest thing to it.

11

You try to make sense of your life. Everybody tries to do that, I think, and part of making sense of things is trying to find reasons . . . or constants . . . things that don't fluctuate.

Everyone does it, but perhaps people who have extraordinarily lucky or unlucky lives do it a little more. Part of you wants to think-or must as least speculatethat you got whopped with the cancer stick because you were one of the bad guys (or one of the good ones, if you believe Durocher's Law). Part of you wants to think that you must have been one hardworking S.O.B. or a real prince or maybe even one of the Sainted Multitude if you end up riding high in a world where people are starving, shooting each other, burning out, bumming out, getting loaded, getting 'Luded.

But there's another part that suggests it's all a lottery, a real-life game-show not much different from "Wheel of Fortune" or "The New Price Is Right" (two of the Bachman books, incidentally, are about game-show-type competitions). It is for some reason depressing to think it was all-or even mostly-an accident. So maybe you try to find out if you could do it again.

Or in my case, if Bachman could do it again.

12

The question remains unanswered. Richard Bachman's first four books did not sell well at all, perhaps partly because they were issued without fanfare.

Each month paperback houses issue three types of books: "leaders," which are heavily advertised, stocked in dump-bins (the trade term for those showy cardboard displays you see at the front of your local chain bookstore), and which usually feature fancy covers that have been either die-cut or stamped with foil;" subleaders, " which are less heavily advertised, less apt to be awarded dump-bins, and less expected to sell millions of copies (two hundred thousand copies sold would be one hell of a good showing for a sub-leader); and just plain books. This third category is the paperback book publishing world's equivalent of trench warfare or … cannon fodder. "Just plain books" (the only other term I can think of is sub-sub-leaders, but that is really depressing) are rarely hardcover reprints; they are generally backlist books with new covers, genre novels (gothics, Regency romances, westerns, and so on), or series books such as The Survivalist, The Mercenaries, The Sexual Adventures of a Horny Pumpkin . . . you get the idea. And, every now and then, you find genuine novels buried in this deep substratum, and the Bachman novels are not the only time such novels have been the work of well-known writers sending out dispatches from deep cover. Donald Westlake published paperback originals under the names Tucker Coe and Richard Stark; Evan Hunter under the name Ed McBain; Gore Vidal under the name Edgar Box. More recently Gordon Lish published an excellent, eerie paperback original called The Stone Boy under a pseudonym.

The Bachman novels were "just plain books," paperbacks to fill the drugstore and bus-station racks of America. This was at my request; I wanted Bachman to keep a low profile. So, in that sense, the poor guy had the dice loaded against him from the start.

And yet, little by little, Bachman gained a dim cult following. His final book, Thinner, had sold about 28,000 copies in hardcover before a Washington bookstore clerk and writer named Steve Brown got suspicious, went to the Library of Congress, and uncovered my name on one of the Bachman copyright forms. Twenty-eight thousand copies isn't a lot-it's certainly not in best-seller territory-but it's 4,000 copies more than my book Night Shift sold in 1978. I had intended Bachman to follow Thinner with a rather gruesome suspense novel called Misery, and I think that one might have taken "Dicky" onto the best-seller lists. Of course we'll never know now, will we? Richard Bachman, who survived the brain tumor, finally died of a much rarer disease-cancer of the pseudonym. He died with that question-is it work that takes you to the top or is it all just a lottery? -still unanswered.

But the fact that Thinner did 28,000 copies when Bachman was the author and 280,000 copies when Steve King became the author, might tell you something, huh?

13

There is a stigma attached to the idea of the pen name. This was not so in the past; there was a time when the writing of novels was believed to be a rather low occupation, perhaps more vice than profession, and a pen name thus seemed a perfectly natural and respectable way of protecting one's self (and one's relatives) from embarrassment. As respect for the art of the novel rose, things changed. Both critics and general readers became suspicious of work done by men and women who elected to hide their identities. If it was good, the unspoken opinion seems to run, the guy would have put his real name on it. If he lied about his name, the book must suck like an Electrolux.

So I want to close by saying just a few words about the worth of these books. Are they good novels? I don't know. Are they honest novels? Yes, I think so. They were honestly meant, anyway, and written with an energy I can only dream about these days (The Running Man, for instance, was written during a period of seventy-two hours and published with virtually no changes). Do they suck like an Electrolux? Overall, no. In places . . . wellll . . .

I was not quite young enough when these stories were written to be able to dismiss them as juvenilia. On the other hand, I was still callow enough to believe in oversimple motivations (many of them painfully Freudian) and unhappy endings. The most recent of the Bachman books offered here, Roadwork, was written between 'Salem's Lot and The Shining, and was an effort to write a "straight" novel. (I was also young enough in those days to worry about that casual cocktail-party question, "Yes, but when are you going to do something serious? ") I think it was also an effort to make some sense of my mother's painful death the year before -- a lingering cancer had taken her off inch by painful inch. Following this death I was left both grieving and shaken by the apparent senselessness of it all. I suspect Roadwork is probably the worst of the lot simply because it tries so hard to be good and to find some answers to the conundrum of human pain.

The reverse of this is The Running Man, which may be the best of them because it's nothing but story-it moves with the goofy speed of a silent movie, and anything which is not story is cheerfully thrown over the side.

Both The Long Walk and Rage are full of windy psychological preachments (both textual and subtextual), but there's still a lot of story in those novels-ultimately the reader will be better equipped than the writer to decide if the story is enough to surmount all the failures of perception and motivation.

I'd only add that two of these novels, perhaps even all four, might have been published under my own name if I had been a little more savvy about the publishing business or if I hadn't been preoccupied in the years they were written with first trying to get myself through school and then to support my family. And that I only published them (and am allowing them to be republished now) because they are still my friends; they are undoubtedly maimed in some ways, but they still seem very much alive to me.

14

And a few words of thanks: to Elaine Koster, NAL's publisher (who was Elaine Geiger when these books were first published), who kept "Dicky's" secret so long and successfully to Carolyn Stromberg, "Dicky's" first editor, who did the same; to Kirby McCauley, who sold the rights and also kept the secret faithfully and well; to my wife, who encouraged me with these just as she did with the others that fumed out to be such big and glittery money-makers; and, as always, to you, reader, for your patience and kindness.

Stephen King

Bangor , Maine

RAGE

Richard Bachman

[24 mar 2001 – scanned for #bookz, proofread and released – v1]

A high school Show-and-Tell session explodes into a nightmare of evil...

So you understand that when we

increase the number of variables,

the axioms themselves never change.

-Mrs. Jean Underwood

Teacher, teacher, ring the be

ll,

My lessons all to you I'll tell,

And when my day at school is through,

I'll know more than aught I knew.

-Children's rhyme, c. 1880

Chapter 1

The morning I got it on was nice; a nice May morning. What made it nice was that I'd kept my breakfast down, and the squirrel I spotted in Algebra II.

I sat in the row farthest from the door, which is next to the windows, and I spotted the squirrel on the lawn. The lawn of Placerville High School is a very good one. It does not fuck around. It comes right up to the building and says howdy. No one, at least in my four years at PHS, has tried to push it away from the building with a bunch of flowerbeds or baby pine trees or any of that happy horseshit. It comes right up to the concrete foundation, and there it grows, like it or not. It is true that two years ago at a town meeting some bag proposed that the town build a pavilion in front of the school, complete with a memorial to honor the guys who went to Placerville High and then got bumped off in one war or another. My friend Joe McKennedy was there, and he said they gave her nothing but a hard way to go. I wish I had been there. The way Joe told it, it sounded like a real good time. Two years ago. To the best of my recollection, that was about the time I started to lose my mind.

Chapter 2

So there was the squirrel, running through the grass at 9:05 in the morning, not ten feet from where I was listening to Mrs. Underwood taking us back to the basics of algebra in the wake of a horrible exam that apparently no one had passed except me and Ted Jones. I was keeping an eye on him, I can tell you. The squirrel, not Ted.

On the board, Mrs. Underwood wrote this: a = 16. "Miss Cross," she said, turning back. "Tell us what that equation means, if you please."

"It means that a is sixteen," Sandra said. Meanwhile the squirrel ran back and forth in the grass, tail bushed out, black eyes shining bright as buckshot. A nice fat one. Mr. Squirrel had been keeping down more breakfasts than I lately, but this morning's was riding as light and easy as you please. I had no shakes, no acid stomach. I was riding cool.