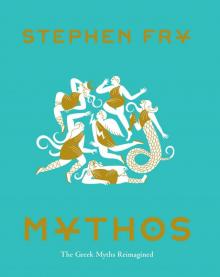

Mythos (2019 Re-Issue)

Stephen Fry

ΜΕ ΑΓ′ΑΠΗ

Text copyright © 2017 by Stephen Fry.

Art copyright © 2017 by the individual licensors.

Pages 325 and 326 are continuations of the copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 2019 by Chronicle Books.

Originally published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Michael Joseph.

ISBN 978-1-4521-7904-9 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-7891-2 (hardcover: alk. paper)

Design by Maggie Edelman.

Cover illustrations by Karolina Schnoor.

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at [email protected] or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

CONTENTS

10 FOREWORD

17 THE BEGINNING, PART ONE

18 Out of Chaos

20 The First Order

22 The Second Order

24 Gaia’s Revenge

29 The Sickle

30 Night and Day, Light and Dark

33 Ouranos Gelded

34 Erinyes, Gigantes, and Meliae

36 From the Foam

38 Rhea

39 The Children of Rhea

41 The Switch

43 The Cretan Child

43 The Oath of Allegiance

45 The Cretan Boy

46 The Oceanid and the Potion

48 Rebirth of the Five

53 THE BEGINNING, PART TWO

54 Clash of the Titans

56 The Proliferation

57 The Muses

60 Threesomes

63 Spirits of Air, Earth, and Water

64 Disposer Supreme and Judge of the Earth

66 The Third Order

66 Hestia

67 The Lottery

68 Hades

69 Poseidon

70 Demeter

71 Hera

72 A New Home

73 The Runt

74 It’s War

75 The Enchanted Throne

77 The Lame One

77 The Hand of Aphrodite

79 The Wedding Feast

83 Food of the Gods

84 Bad Zeus

85 The Mother of All Migraines

88 Athena

90 Metis Within

91 Seeking Sanctuary

92 Twins!

93 Artemis

96 Apollo

97 The Wrath of Hera

99 Maia Maia

99 The Infant Prodigy

101 Apollo Reads the Signs

102 Half Brothers

106 The Twelfth God

108 The Olympians

111 THE TOYS OF ZEUS, PART ONE

112 Prometheus

115 Kneading and Firing

116 A Reduced Set

117 A Name Is Found

119 The Golden Age

120 The Fennel Stalk

121 The Gift of Fire

124 The Punishments

124 The Gift

125 The Brothers

126 When It’s a Jar

129 The Chest, the Waters, and the Bones of Gaia

132 Death

135 Prometheus Bound

138 Persephone and the Chariot

140 The Pomegranate Seeds

142 Hermaphroditus and Silenus

144 Cupid and Psyche

144 Erotes

145 Love, Love, Love

146 Psyche

147 Prophecy and Abandonment

149 The Enchanted Castle

150 Voices, Visions, and a Visitor

153 Sisters

157 A Drop of Oil

160 Alone

162 The Tasks of Aphrodite

164 The Union of Love and Soul

167 THE TOYS OF ZEUS, PART TWO

168 Mortals

168 Io

171 The Semen-Soaked Scarf

172 Phaeton

174 The Son of the Sun

174 Father and Sun

178 Daybreak

179 The Drive

180 The Fallout

182 Cadmus

182 The White Bull

183 The Quest for Europa

185 The Oracle Speaks

186 The Phocian Games

188 The Water Dragon

190 The Dragon’s Teeth

192 The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmonia

194 Consigned to the Dust

196 Twice Born

196 The Eagle Lands

197 The Eagle’s Wife

200 The Manifestation

201 The Newest God

204 Thirteen at Table

206 The Beautiful and the Damned: Angry Goddesses

206 Actaeon

207 Erysichton

210 The Doctor and the Crow

210 The Birth of Medicine

214 Crime and Punishment

214 Ixion

216 Consequences

217 Tantalus

219 Sisyphus

219 Brotherly Love

221 Sisyphean Tasks

222 The Eagle

224 Cheating Death

225 Life without Death

227 Burial Rites

229 Rolling the Rock

232 Hubris

232 All Tears

234 Apollo and Marsyas: Puffed Cheeks

235 The Competition

237 Judgment

239 Arachne

239 The Weaver

241 The Weave-Off

244 The Reward

245 More Metamorphoses

245 Nisus and Scylla

246 Callisto

247 Procne and Philomela

248 Ganymede and the Eagle

250 Moon Lovers

253 Lailaps and Alopex Teumesios

255 Endymion

256 Eos and Tithonus

256 Love at First Sight

257 The Boon

258 Be Careful What You Wish For

259 The Grasshopper

261 The Bloom of Youth

261 Hyacinthus

261 Crocus and Smilax

262 Aphrodite and Adonis

265 Echo and Narcissus

265 Tiresias

266 Narcissus

267 Echo

268 Echolalia

270 Echo and Narcissus

272 The Boy in the Water

273 The Gods Take Pity

275 Lovers

275 Pyramus and Thisbe

278 Galateas

278 Acis and Galatea

278 Galatea II

279 Leucippos II, Daphne, and Apollo

280 Galatea III and Pygmalion Too

285 Hero and Leander

288 Arion and the Dolphin

289 Overboard

292 The Monument

295 Philemon and Baucis, or Hospitality Rewarded

300 Phrygia and the Gordian Knot

302 Midas

302 The Ugly Stranger

304 Goldfinger

306 King Midas’s Ears

311 APPENDICES

312 The Brothers, a Sidebar

314 Hope

315 Giant Leaps

316 Feet and Toes

318 AFTERWORD

318 Myth v. Legend v. Religion

320 The Greeks

&n

bsp; 320 Location, Location

321 Sources Ancient

322 Sources Modern

323 Spelling the Names

323 Saying the Names

324 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

325 PICTURE CREDITS

328 INDEX

352 About the Author

FOREWORD

I was lucky enough to pick up a book called Tales from Ancient Greece when I was quite small. It was love at first meeting. Much as I went on to enjoy myths and legends from other cultures and peoples, there was something about these Greek stories that lit me up inside. The energy, humor, passion, particularity, and believable detail of their world held me enthralled from the very first. I hope they will do the same for you. Perhaps you already know some of the myths told here, but I especially welcome those who may never have encountered the characters and stories of Greek myth before. You don’t need to know anything to read this book; it starts with an empty universe. Certainly no “classical education” is called for, no knowledge of the difference between nectar and nymphs, satyrs and centaurs, or the Fates and the Furies is required. There is absolutely nothing academic or intellectual about Greek mythology; it is addictive, entertaining, approachable, and astonishingly human.

But where did they come from, these myths of ancient Greece? In the tangle of human history we may be able to pull on a single Greek thread and follow it back, but by picking out only one civilization and its stories we might be thought of as taking liberties with the true source of universal myth. Early human beings the world over wondered at the sources of power that fueled volcanoes, thunderstorms, tidal waves, and earthquakes. They celebrated and venerated the rhythm of the seasons, the procession of heavenly bodies in the night sky, and the daily miracle of the sunrise. They questioned how it might all have started. The collective unconscious of many civilizations has told stories of angry gods; dying and renewing gods; fertility goddesses; deities; demons; and spirits of fire, earth, and water.

Of course the Greeks were not the only people to weave a tapestry of legends and lore out of the puzzling fabric of existence. The gods of Greece, if we are archaeological and palaeoanthropological about it all, can be traced back to the sky fathers, moon goddesses, and demons of the “fertile crescent” of Mesopotamia—today’s Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. The Babylonians, Sumerians, Akkadians, and other civilizations there, which first flourished far earlier than the Greeks, had their creation stories and folk myths which, like the languages that expressed them, could find ancestry in India and thence westward back to prehistory, Africa, and the birth of our species.

But whenever we tell any story we have to snip the narrative string somewhere in order to make a starting point. It is easy to do this with Greek mythology because it has survived with a detail, richness, life, and color that distinguish it from other mythologies. It was captured and preserved by the very first poets and has come down to us in an unbroken line from almost the beginning of writing to the present day. While Greek myths have much in common with Chinese, Iranian, Indian, Mayan, African, Russian, Native American, Hebrew, and Norse myths, they are uniquely—as the writer and mythographer Edith Hamilton put it—“the creation of great poets.” The Greeks were the first people to make coherent narratives, a literature even, of their gods, monsters, and heroes.

The arc of the Greek myths follows the rise of mankind, our battle to free ourselves from the interference of the gods—their abuse, their meddling, their tyranny over human life and civilization. Greeks did not grovel before their gods. They were aware of their vain need to be supplicated and venerated, but they believed men were their equal. Their myths understand that whoever created this baffling world, with its cruelties, wonders, caprices, beauties, madness, and injustice, must themselves have been cruel, wonderful, capricious, beautiful, mad, and unjust. The Greeks created gods that were in their image: warlike but creative, wise but ferocious, loving but jealous, tender but brutal, compassionate but vengeful.

Mythos begins at the beginning, but it does not end at the end. Had I included heroes like Oedipus, Perseus, Theseus, Jason, and Heracles and the details of the Trojan War, this book would have been too heavy even for a Titan to pick up. Moreover, I am only concerned with telling the stories, not with explaining them or investigating the human truths and psychological insights that may lie behind them. The myths are fascinating enough in all their disturbing, surprising, romantic, comic, tragic, violent, and enchanting detail to stand on their own as stories. If, as you read, you cannot help wondering what inspired the Greeks to invent a world so rich and elaborate in character and incident, and you find yourself pondering the deep truths that the myths embody—well, that is certainly part of the pleasure.

And pleasure is what immersing yourself in the world of Greek myth is all about.

Stephen Fry

The Second Order

The Olympians

*Hades is not technically an Olympian, as he spent all of his time in the underworld.

THE BEGINNING

Part One

OUT OF CHAOS

These days the origin of the universe is explained by proposing a Big Bang, a single event that instantly brought into being all the matter from which everything and everyone are made.

The ancient Greeks had a different idea. They said that it all started not with a bang, but with CHAOS.

Was Chaos a god—a divine being—or simply a state of nothingness? Or was Chaos, just as we would use the word today, a kind of terrible mess, like a teenager’s bedroom only worse?

Think of Chaos perhaps as a kind of grand cosmic yawn.

As in a yawning chasm or a yawning void.

Whether Chaos brought life and substance out of nothing or whether Chaos yawned life up or dreamed it up, or conjured it up in some other way, I don’t know. I wasn’t there. Nor were you. And yet in a way we were, because all the bits that make us were there. It is enough to say that the Greeks thought it was Chaos who, with a massive heave, or a great shrug, or hiccup, vomit, or cough, began the long chain of creation that has ended with pelicans and penicillin and toadstools and toads, sea lions, seals, lions, human beings, and daffodils and murder and art and love and confusion and death and madness and biscuits.

Whatever the truth, science today agrees that everything is destined to return to Chaos. It calls this inevitable fate entropy: part of the great cycle from Chaos to order and back again to Chaos. Your trousers began as chaotic atoms that somehow coalesced into matter that ordered itself over eons into a living substance that slowly evolved into a cotton plant that was woven into the handsome stuff that sheathes your lovely legs. In time you will abandon your trousers—not now, I hope—and they will rot down in a landfill or be burned. In either case their matter will at length be set free to become part of the atmosphere of the planet. And when the sun explodes and takes every particle of this world with it, including the ingredients of your trousers, all the constituent atoms will return to cold Chaos. And what is true for your trousers is of course true for you.

So the Chaos that began everything is also the Chaos that will end everything.

Now, you might be the kind of person who asks, “But who or what was there before Chaos?” or “Who or what was there before the Big Bang? There must have been something.”

Well, there wasn’t. We have to accept that there was no “before,” because there was no Time yet. No one had pressed the start button on Time. No one had shouted Now! And since Time had yet to be created, time words like “before,” “during,” “when,” “then,” “after lunch,” and “last Wednesday” had no possible meaning. It screws with the head, but there it is.

The Greek word for “everything that is the case,” what we could call “the universe,” is COSMOS. And at the moment—although “moment” is a time word and makes no sense just now (neither does the phrase “just now”)—at the moment, Cosmos is Chaos and only Chaos because Chaos is the only thing that is the case. A stretching, a tuning up of the orchestra .

. .

But things are about to change very quickly.

THE FIRST ORDER

From formless Chaos sprang two creations: EREBUS and NYX. Erebus, he was darkness, and Nyx, she was night. They coupled at once and the flashing fruits of their union were HEMERA, day, and AETHER, light.

At the same time—because everything must happen simultaneously until Time is there to separate events—Chaos brought forth two more entities: GAIA, the earth, and TARTARUS, the depths and caves beneath the earth.

I can guess what you might be thinking. These creations sound charming enough—Day, Night, Light, Depths, and Caves. But these were not gods and goddesses, they were not even personalities. And it may have struck you also that since there was no time there could be no dramatic narrative, no stories; for stories depend on Once Upon a Time and What Happened Next.

You would be right to think this. What first emerged from Chaos were primal, elemental principles that were devoid of any real color, character, or interest. These were the PRIMORDIAL DEITIES, the First Order of divine beings from whom all the gods, heroes, and monsters of Greek myth spring. They brooded over and lay beneath everything . . . waiting.

The silent emptiness of this world was filled when Gaia bore two sons all on her own.1 The first was PONTUS, the sea, and the second was OURANOS, the sky—better known to us as Uranus, the sound of whose name has ever been the cause of great delight to children from nine to ninety. Hemera and Aether bred too, and from their union came THALASSA, the female counterpart of Pontus the sea.

Ouranos, who preferred to pronounce himself Ooranoss, was the sky and the heavens in the way that—at the very beginning—the primordial deities always were the things they represented and ruled over.2 You could say that Gaia was the earth of hills, valleys, caves, and mountains yet capable of gathering herself into a form that could walk and talk. The clouds of Ouranos the sky rolled and seethed above her but they too could coalesce into a shape we might recognize. It was so early on in the life of everything. Very little was settled.

Gaia, a primordial goddess and the personification of the Earth, brought into being at the dawn of creation.

1. This trick of virgin birth, or parthenogenesis, can be found in nature still. In aphids, some lizards, and even sharks, it is a reasonably common way to have young. There won’t be the variation that two sets of genes allow; this is the same in the genesis of the Greek gods. The interesting ones are all the fruit of two parents, not one.