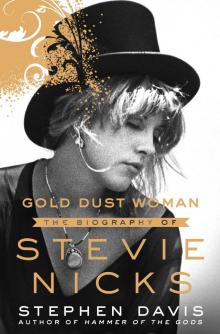

Gold Dust Woman

Stephen Davis

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Photos

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Fan is short for fanatic. This biography is dedicated to all the fans of Stevie Nicks (and Fleetwood Mac) past and present, memor et fidelis. Non nobis solum nati sumus.

Blessed Cecilia, appear in visions

To all musicians, appear and inspire:

Translated Daughter, come down and startle

Composing mortals with immortal fire.

—W.H. AUDEN

Chiffon lasts forever if you take good care of it.

—STEVIE NICKS

PREFACE

Back then … she’s a complete unknown, the new girl in an old band.

She’s standing on a soundstage in Los Angeles, about to make her national television debut. She’s trembling slightly as she waits on her taped mark while the director explains that if she steps away from the microphone, she’ll be off camera.

If she’s scared, she’s determined, she said later, not to let it show. While she waits, she holds the microphone stand with both hands to keep steady. She tells herself to clear her mind.

It’s June 11, 1975, and semi-washed-up English blues band Fleetwood Mac is making its first video with its new-look Anglo-American lineup. The song they’re about to play is “Rhiannon,” written by the new girl in the band, Stevie Nicks. She’s about to sing her most important song to America for the first time.

She should tremble, other than from the excitement of the video shoot in front of a small studio audience. This “Rhiannon” performance is Make or Break for the not-young singer-songwriter. An elderly ingénue at the age of twenty-eight, she’s been kicking around California’s booming music business for seven years already, with little to show for it other than a bulging songbook and an interesting boyfriend, who’s standing next to her on the stage with his guitar, getting ready to inject a dose of “Rhiannon” into the American consciousness, like an enchantment from the misty mountains of farthest Wales.

Do or die—because if this new iteration of Fleetwood Mac fails to catch on, for Stevie Nicks it’s back to waiting tables wearing a corny period uniform in West Hollywood. And the auguries aren’t great at this point. Her singing had been panned—put down—by Rolling Stone magazine in its review of Fleetwood Mac’s new album. She also knew that she was only in Fleetwood Mac because her boyfriend told the band that if they wanted him as their new guitar player, they had to take her as well.

As the stage manager counts down the time, Stevie Nicks looks over at the boyfriend—Lindsey Buckingham. “Linds.” He’s a year younger than she is. He’s in his stage outfit, a floppy silk kimono top, very Robert Plant, with lots of visible chest hair and an ample ’fro of dark curly locks. He smiles at her and winks—he’s nervous, too. But this is their moment—what they’ve been after, for years. She’s all in black, her blond hair layered in a feathered shag perm with platinum highlights. She’s a breath over five feet, a tiny girl really, but the fashionably stacked heels of her black boots add an extra four inches. A lacy black cape made of light chiffon completes the ensemble. She’s wearing a lot of eye shadow. She looks amazing, made for television like all the rock stars. (The formal, witchy top hat will come later. This is pre-Rumours. One day in the next century there will be websites devoted to her collection of shawls.)

But now the red studio light flashes on, Stevie takes a half step back, and Lindsey starts the song, cuffing his electric guitar. Drummer Mick Fleetwood pulses the rhythm forward with bassist John McVie, whose wife Christine sits at her electric keyboards, stage left, playing bluesy chords. Now Stevie steps forward and speaks into the microphone her first-ever words to her future rabid fans:

“This is a song,” she intones in a western drawl, “about an old Welsh witch.” And then she lets Rhiannon cast her magic cathode-ray spell. The song lasts almost seven minutes. Stevie pushes the beat with an arm gesture, and Fleetwood kicks it. “Rhiannon rings like a bell through the night and wouldn’t you love to love her? She rules her life like a bird in flight, and who will be her lover?” Stevie sways with the beat, in close eye contact with Lindsey by her side. She wails “taken by the sky, taken by the wind,” a powerful female spirit vanishing in the ether, leaving no trace except the pretty guitar licks, and this young woman dancing power twirls on her mark between the second and third verses. She sings lyrics slightly different from those on the records: “Once in a million years / A lady like her … rises.” She and Lindsey and Christine all sing together the keening, breathy chorus—“Rhiaaaaa-nnon. Rhiaaaaaaaaaa-nnon.”

Lindsey is rocking out and smiling. It’s totally happening now. Fleetwood Mac is nailing this. “She is like a cat in the dark, and then she is the darkness … Would you stay if she promised you heaven? Will you ever win?”

Then the music softens as Christine plays a bluesy keyboard solo that sets up the sonic whirlwind to come. Stevie stretches her gauzy black cape out like a pair of wings, fluid stagecraft before the song’s next movement. (“Rhiannon” in performance can be seen as a five-scene playlet.) At just after four minutes the beat recedes, and Stevie sings the midsection: “Dreams unwind / Love’s a state of mind.” And then, with two minutes to go, the band launches into a militant 4/4 march with Stevie in a hieratic trance—shouting, yelling, wailing lyrics, waving arms, strutting and stomping, acting out, wild-eyed. She’s shaking and vibrating, screaming like a bloody Bacchant, ready to tear the soul out of your body, her gesturing fingers making portents and prophesies in the smoky air.

The song crashes finally to a halt—“You cry / But she’s gone”—as she lets out a final howl that lasts ten seconds, descending by octaves. Then Stevie bends way down into a deep floor bow, grasping the microphone stand with both hands to prevent an exhausted collapse. The performance is complete; the studio audience applauds, and the image fades from the screen.

*

When the “Rhiannon” video was broadcast months later on The Midnight Special, the syndicated (nonnetwork) rock concert program shown late on Friday nights in the seventies, it changed everything for Fleetwood Mac. The band’s eponymous new album, released the previous summer, had been chugging along, selling the usual mid-chart numbers to the band’s loyal audience, although the first single, Christine’s “Over My Head,” had gotten airplay on FM radio’s soft rock/adult contemporary format and had jumped to Billboard magazine’s #20 chart position.

Then the “Rhiannon” 45-rpm single was released in February 1976 and exploded like a radio grenade after the enormous rock audience saw Stevie Nicks celebrate the rite of the old Welsh witch on national television. Suddenly a million American girls went out and bought the new Fleetwood Mac album. Then a million more. The “Rhiannon” album track immediately jumped on every American FM rock station’s playlist, while the remixed single—which sounded hotter on a tinny car radio—crossed from FM onto AM radio and into the A&W Root Beer drive-ins of middle America. The White Goddess’s momentum turned into massive album sales, and to the s

hock of everyone (but the band), the Fleetwood Mac album hit #1 on the Billboard Hot Hundred, and stayed there for weeks.

When Fleetwood Mac found out about their number-one album, they were already making their next album—Rumours. But whenever they turned on their car radios, now “Rhiannon” was riding the airwaves with them. The old Welsh witch had done her job.

*

Who is Rhiannon?

The song doesn’t give away any information on her, but it offers a transcendent signal—the sky, the wind, flying—that was picked up by the daughters of the enormous Welsh-descended population of North America, like an occluded racial memory from olden days, before the time of memory. Even Stevie Nicks, who had so ardently conjured Rhiannon, admitted that she hardly knew what she was writing about. (“I read this novel, I loved the name. We felt she was a queen, and her memory became a myth.”) Later, Stevie learned much more. Rhiannon was an ancient Welsh goddess, and this affected the spiritually minded singer, because Stevie was of almost pure Welsh extraction herself.

Wales and its legends are important to this story—how a beautiful Welsh-descended daughter of the American Southwest became a rock goddess herself and then sustained a decades-long international career, at the very top of her profession.

*

Wales occupies the westernmost territory of Great Britain, a land of misty mountains, drowned cities, and legendary giants. The Celtic tribes of the British Isles regarded Wales as a holy and haunted place since time immemorial, a sere landscape imbued with tremendous spiritual power. When the priestly Druids built Stonehenge, their prehistoric solar observatory on Salisbury Plain, they obtained the enormous bluestone monoliths from the Preseli Mountains in Wales, a hundred miles away. Even today nobody knows how the Druids rolled their stones down to Wiltshire.

Julius Caesar invaded Britannia, and the Romans ruled for centuries. After they left, Britain was occupied by migrating German nations. The native Celtic tribes were pushed west to Wales, a less fertile and hospitable landscape. Over the next thousand years, the Welsh people assumed the traits that still describe their intense nationality and a love of poetry and singing, especially choral music. The Welsh also came to be associated with otherworldliness and magic. Merlin, the magician of the Arthurian legends, was born in Wales. So was Morgan le Fay, King Arthur’s sister, another old Welsh witch. The “blessed island” of Avalon is just offshore. This national propensity for magic and spells cannot be discounted when thinking about Stevie Nicks.

Life in Wales was hard for its people, who farmed the stony fields, raised sheep and cattle, and fished in the violent swells of the craggy Welsh coastline. The other occupation was mining, first for tin and copper, later for iron and coal. The women worked as hard as the men. They found relief at the famous Welsh festivals that featured choral competitions and riotous, mead-fueled word games where poetic champions composed spontaneous verse to determine the national poets laureate. The Welsh bards and minstrels sang of Dylan, “the son of the wave,” a child-god in the shape of a fish; of the sisters of the holy wells; of sacred twins; and of the Three Birds of Rhiannon, the goddess who seems to change from a little moon to a mare goddess, or to a nightmare, according to the old stories in the Welsh Triads and The Mabinogion.

William Shakespeare had a Welsh grandmother, Alys Griffin. The heir to the English throne is the Prince of Wales. The wild Welsh spirit inhabits the cultures of England, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. It preserves something of the essence of the older Celtic-romantic traditions of the west—Western civilization.

Beginning in the 1600s, Welsh people joined the migrations to North America for opportunity and a better life by the tens of thousands, later swelling to millions. Many fleeing poverty arrived in bonded or indentured servitude. In return for passage from Cardiff to ports in Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas, the bonded servant owed his or her master seven years of service. Then they were free to go their own way. So was the American South and Mid-South populated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By 1900 more than half the names in American telephone directories—Jones, Lewis, Evans, Wilson, Williams, Thomas, Hopkins, Jenkins, Perkins, Davis—were descended from the epochal Welsh migrations to North America.

Some researchers think Stevie Nicks’s ancestors arrived sometime in the mid-1700s, when the surname Nicks appeared in ship manifests in the Baltimore area. (In northern Celtic folklore, a “nixie” is a female sea sprite, a water-wraith related to the kelpie, the mythic sea spirit of the Scottish Isles. “There are nicks in sea, lake, river, and waterfall,” according to the old books of fairy lore.) The migrants from Wales were mostly Protestant, often Methodist, and the choral culture of their churches is thought to have been absorbed by slave religion in the South; some musicologists link the Welsh harmonic influence to the development of African-American gospel choirs.

By 1950, a crucial Welsh influence had appeared in America in the form of the roaring young poet Dylan Thomas, from Swansea, south Wales; his stirring, bardic cadences, delivered in a mellifluous Welsh baritone, spread from coast to coast through recordings and readings during the 1950s, a major inspiration for the Beat Generation writers and other modernist poets.

In the mid-fifties, Welsh-descended musicians invented rock & roll music in America’s Mid-South. The Welsh name Elvis means what it sounds like—elfin, impish, otherworldly. And Presley is another way to spell Preseli, the Welsh mountains that provided the Druidical “sarsen stones” of Stonehenge. Just the name “Elvis Presley” must have conjured an atavistic signal. Welsh mountain spirit! Could this help to explain the hysterical reactions of white Southern girls to Elvis the Pelvis’s uninhibited gyrations in Tennessee and Arkansas, Alabama and Louisiana, in 1954? Was an ancient and forgotten Welsh god reborn as a young one in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1935? Most of the other early rockers were Welsh, too: Jerry Lee Lewis from Ferriday, Louisiana; Carl Perkins and the Everly Brothers from Tennessee; Conway Twitty (born Harold Jenkins) from Arkansas. Same with Ronnie Hawkins and Levon Helm. Even Johnny Cash and a lot of the country and western stars: Loretta Lynn. Buck Owens. Kitty Wells. Hank Williams.

A few years later, in 1960, when a young folk singer from Minnesota named Robert Zimmerman moved to New York City to try his luck, and he needed a new identity for credibility in the commercial folk revival, he changed his name to Bob Dylan.

The founder of the Rolling Stones, Brian Jones (born Lewis Brian Hopkin-Jones), had Welsh blood. David Bowie’s real name was David Jones. Ray Davies. Robert Plant and Jimmy Page both had Welsh ancestors, and even retreated to Wales to write music for Led Zeppelin. “Bron-Yr-Aur.” Misty Mountain Hop, indeed. Stevie Nicks, herself a poet of sometimes exquisite technical skill in terms of cadence and scansion, is firmly in this tradition, the venerable Welsh legacy of professional bardic championship.

*

Now, more than forty years after the mid-seventies’ success of “Rhiannon,” Stevie Nicks herself is an old Welsh witch. She’s the acknowledged Fairy Godmother of Rock. Fleetwood Mac went on to make Rumours, one of the bestselling recordings in history, then on to worlds beyond, and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. It’s the same with Stevie Nicks, whose wildly successful solo career continues into the time of this writing. In fact, she’s bigger than ever, with legions of loyal fans thronging her concerts, dressing like her, identifying with her—beyond the music itself. (Other than Stevie, only Led Zeppelin enjoys this sort of mystical bond with its multigenerational audience.) Since 1981, Stevie’s fans have immersed themselves in the dark velvet rooms she creates in her songs, from the epic to the heartbroken, through loss and failure, from addiction to recovery. For her fans, Stevie Nicks fills many different roles. She’s an elegist and an analyst of romantic longings. She’s a chronicler of remorse and regret. Her work has an organic core of a woman artist according a tragic dignity to a failed marriage between two ambitious people, as well as to the oblique charms of a broken life. Always in her songs there are notes of

tailored elegance amid the agonies of her disasters. Through the music, she’s able to override her own troubles and move on. Stevie Nicks is too busy working on the next project to worry about redemption. She seems to tell us that we’re all worth more than what “happens” to us. She’s a mood of her own, “a will to wistfulness,” a candle of hope, or maybe just a wish. Through the songs comes self-realization and emotional commitment. They are cathartic for her and her audience. Memories, dreams, and the passing of time are her special subjects. Stevie’s fans owe her greatest songs to her compulsion to externalize her experiences, to let them all hang out, to use them to express her feelings: first in poems and drawings, then in songs, recordings, costume, and performance, with the ultimate goal of ensuring that her life, and her life’s work, can never fade beyond memory. The appropriate response of her fans to this golden presence, which seems to embody the idea that we all have sacred powers within us, is worship and love.

In 1979, “Gold Dust Woman” was a chilling prophesy of excess and failure that came true. This biography is an attempt to describe its subject as a fully externalized public woman with an ongoing career, in and out of Fleetwood Mac. Anyone who writes about Stevie Nicks soon learns that there are things she doesn’t want anyone to know and which no one will ever know. Any biographer should think this challenging, seductive, admirable. “I’m stranger than most people,” Stevie said awhile ago. In the end, her songs and music tell most of her story, certainly the important parts of it. To current interviewers, Stevie insists she has more work to do. Her fans know that her art will last as long as it remains in the keeping of those who understand its emotional value, its deepest meanings, and the transcendental distinction of her music and her life.

—S.D. 2017

CHAPTER 1

1.1 Teedie

The frontier state of Arizona is the keystone of the American Southwest, wedged between California and New Mexico. The climate is arid and dry, the landscape monumental and gigantic. In the years after the Second World War when she was born, Arizona still had a Western frontier look. The people were the grandchildren of frontier families, solid and outgoing. The cactus was the state emblem. Native American tribes lived on their reservations, a world apart from “Anglo” society, as it was called. The bigger cities—Phoenix and Tucson—were expanding out into the desert, fueled by postwar migration to a promised land of opportunity and bright sunshine in the winter.