The O'Ruddy: A Romance

Stephen Crane

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, David Edwards, and theOnline Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net(This file was produced from images generously madeavailable by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

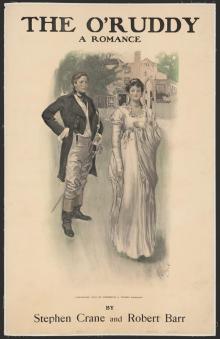

THE O'RUDDY

_A ROMANCE_

BY

STEPHEN CRANE

_Author of "The Red Badge of Courage," "Active Service," "Wounds in the Rain," etc._

AND

ROBERT BARR

_Author of "Tekla," "In the Midst of Alarms," "Over the Border," "The Victors," etc._

_With frontispiece by_

C. D. WILLIAMS

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

_Copyright, 1903,_

BY FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

* * * * *

THE O'RUDDY

CHAPTER I

My chieftain ancestors had lived at Glandore for many centuries andwere very well known. Hardly a ship could pass the Old Head of Kinsalewithout some boats putting off to exchange the time of day with her,and our family name was on men's tongues in half the seaports ofEurope, I dare say. My ancestors lived in castles which were likechurches stuck on end, and they drank the best of everything amid thejoyous cries of a devoted peasantry. But the good time passed awaysoon enough, and when I had reached the age of eighteen we had nobodyon the land but a few fisher-folk and small farmers, people who werealmost law-abiding, and my father came to die more from disappointmentthan from any other cause. Before the end he sent for me to come tohis bedside.

"Tom," he said, "I brought you into existence, and God help you safeout of it; for you are not the kind of man ever to turn your hand towork, and there is only enough money to last a gentleman five moreyears.

"The 'Martha Bixby,' she was, out of Bristol for the West Indies, andif it hadn't been for her we would never have got along this far withplenty to eat and drink. However, I leave you, besides the money, thetwo swords,--the grand one that King Louis, God bless him, gave me,and the plain one that will really be of use to you if you get into adisturbance. Then here is the most important matter of all. Here aresome papers which young Lord Strepp gave me to hold for him when wewere comrades in France. I don't know what they are, having had verylittle time for reading during my life, but do you return them to him.He is now the great Earl of Westport, and he lives in London in agrand house, I hear. In the last campaign in France I had to lend hima pair of breeches or he would have gone bare. These papers areimportant to him, and he may reward you, but do not you depend on it,for you may get the back of his hand. I have not seen him for years. Iam glad I had you taught to read. They read considerably in England, Ihear. There is one more cask of the best brandy remaining, and Irecommend you to leave for England as soon as it is finished. And now,one more thing, my lad, never be civil to a king's officer. Whereveryou see a red coat, depend there is a rogue between the front and theback of it. I have said everything. Push the bottle near me."

Three weeks after my father's burial I resolved to set out, with nomore words, to deliver the papers to the Earl of Westport. I wasresolved to be prompt in obeying my father's command, for I wasextremely anxious to see the world, and my feet would hardly wait forme. I put my estate into the hands of old Mickey Clancy, and told himnot to trouble the tenants too much over the rent, or they probablywould split his skull for him. And I bid Father Donovan look out forold Mickey Clancy, that he stole from me only what was reasonable.

I went to the Cove of Cork and took ship there for Bristol, andarrived safely after a passage amid great storms which blew us so nearGlandore that I feared the enterprise of my own peasantry. Bristol, Iconfess, frightened me greatly. I had not imagined such a huge andteeming place. All the ships in the world seemed to lie there, and thequays were thick with sailor-men. The streets rang with noise. Isuddenly found that I was a young gentleman from the country.

I followed my luggage to the best inn, and it was very splendid, fitto be a bishop's palace. It was filled with handsomely dressed peoplewho all seemed to be yelling, "Landlord! landlord!" And there was alittle fat man in a white apron who flew about as if he were beingstung by bees, and he was crying, "Coming, sir! Yes, madam! At once,your ludship!" They heeded me no more than if I had been an emptyglass. I stood on one leg, waiting until the little fat man shouldeither wear himself out or attend all the people. But it was to nopurpose. He did not wear out, nor did his business finish, so finallyI was obliged to plant myself in his way, but my speech was decentenough as I asked him for a chamber. Would you believe it, he stoppedabruptly and stared at me with sudden suspicion. My speech had been socivil that he had thought perhaps I was a rogue. I only give you thisincident to show that if later I came to bellow like a bull with thebest of them, it was only through the necessity of proving tostrangers that I was a gentleman. I soon learned to enter an inn as adrunken soldier goes through the breach into a surrendering city.

Having made myself as presentable as possible, I came down from mychamber to seek some supper. The supper-room was ablaze with light andwell filled with persons of quality, to judge from the noise that theywere making. My seat was next to a garrulous man in plum-colour, whoseemed to know the affairs of the entire world. As I dropped into mychair he was saying--

"--the heir to the title, of course. Young Lord Strepp. That ishe--the slim youth with light hair. Oh, of course, all in shipping.The Earl must own twenty sail that trade from Bristol. He is postingdown from London, by the way, to-night."

You can well imagine how these words excited me. I half arose from mychair with the idea of going at once to the young man who had beenindicated as Lord Strepp, and informing him of my errand, but I had asudden feeling of timidity, a feeling that it was necessary to beproper with these people of high degree. I kept my seat, resolving toaccost him directly after supper. I studied him with interest. He wasa young man of about twenty years, with fair unpowdered hair and aface ruddy from a life in the open air. He looked generous and kindly,but just at the moment he was damning a waiter in language that wouldhave set fire to a stone bridge. Opposite him was a clear-eyedsoldierly man of about forty, whom I had heard called "Colonel," andat the Colonel's right was a proud, dark-skinned man who kept lookingin all directions to make sure that people regarded him, seated thuswith a lord.

They had drunk eight bottles of port, and in those days eight bottlescould just put three gentlemen in pleasant humour. As the ninth bottlecame on the table the Colonel cried--

"Come, Strepp, tell us that story of how your father lost his papers.Gad, that's a good story."

"No, no," said the young lord. "It isn't a good story, and besides myfather never tells it at all. I misdoubt it's truth."

The Colonel pounded the table. "'Tis true. 'Tis too good a story to befalse. You know the story, Forister?" said he, turning to thedark-skinned man. The latter shook his head.

"Well, when the Earl was a young man serving with the French he ratherrecklessly carried with him some valuable papers relating to someestates in the North, and once the noble Earl--or Lord Strepp as hewas then--found it necessary, after fording a stream, to hang hisbreeches on a bush to dry, and then a certain blackguard of a wildIrishman in the corps came along and stole--"

But I had arisen and called loudly but with dignity up the long table,"That, sir, is a lie." The room

came still with a bang, if I may beallowed that expression. Every one gaped at me, and the Colonel's faceslowly went the colour of a tiled roof.

"My father never stole his lordship's breeches, for the good reasonthat at the time his lordship had no breeches. 'Twas the other way. Myfather--"

Here the two long rows of faces lining the room crackled for a moment,and then every man burst into a thunderous laugh. But I had flung tothe winds my timidity of a new country, and I was not to be put downby these clowns.

"'Tis a lie against an honourable man and my father," I shouted. "Andif my father hadn't provided his lordship with breeches, he would havegone bare, and there's the truth. And," said I, staring at theColonel, "I give the lie again. We are never obliged to give it twicein my country."

The Colonel had been grinning a little, no doubt thinking, along witheverybody else in the room, that I was drunk or crazy; but this lasttwist took the smile off his face clean enough, and he came to hisfeet with a bound. I awaited him. But young Lord Strepp and Foristergrabbed him and began to argue. At the same time there came down uponme such a deluge of waiters and pot-boys, and, may be, hostlers, thatI couldn't have done anything if I had been an elephant. They werefrightened out of their wits and painfully respectful, but all thesame and all the time they were bundling me toward the door. "Sir!Sir! Sir! I beg you, sir! Think of the 'ouse, sir! Sir! Sir! Sir!" AndI found myself out in the hall.

Here I addressed them calmly. "Loose me and takes yourselves offquickly, lest I grow angry and break some dozen of these woodenheads." They took me at my word and vanished like ghosts. Then thelandlord came bleating, but I merely told him that I wanted to go tomy chamber, and if anybody inquired for me I wished him conducted upat once.

In my chamber I had not long to wait. Presently there were steps inthe corridor and a knock at my door. At my bidding the door opened andLord Strepp entered. I arose and we bowed. He was embarrassed andrather dubious.

"Aw," he began, "I come, sir, from Colonel Royale, who begs to beinformed who he has had the honour of offending, sir?"

"'Tis not a question for your father's son, my lord," I answeredbluntly at last.

"You are, then, the son of The O'Ruddy?"

"No," said I. "I am The O'Ruddy. My father died a month gone andmore."

"Oh!" said he. And I now saw why he was embarrassed. He had fearedfrom the beginning that I was altogether too much in the right. "Oh!"said he again. I made up my mind that he was a good lad. "That isdif--" he began awkwardly. "I mean, Mr. O'Ruddy--oh, damn it all, youknow what I mean, Mr. O'Ruddy!"

I bowed. "Perfectly, my lord!" I did not understand him, of course.

"I shall have the honour to inform Colonel Royale that Mr. O'Ruddy isentitled to every consideration," he said more collectedly. "If Mr.O'Ruddy will have the goodness to await me here?"

"Yes, my lord." He was going in order to tell the Colonel that I was agentleman. And of course he returned quickly with the news. But he didnot look as if the message was one which he could deliver with a glibtongue. "Sir," he began, and then halted. I could but courteouslywait. "Sir, Colonel Royale bids me say that he is shocked to find thathe has carelessly and publicly inflicted an insult upon an unknowngentleman through the memory of the gentleman's dead father. ColonelRoyale bids me to say, sir, that he is overwhelmed with regret, andthat far from taking an initial step himself it is his duty to expressto you his feeling that his movements should coincide with anyarrangements you may choose to make."

I was obliged to be silent for a considerable period in order togather head and tail of this marvellous sentence. At last I caught it."At daybreak I shall walk abroad," I replied, "and I have no doubtthat Colonel Royale will be good enough to accompany me. I knownothing of Bristol. Any cleared space will serve."

My Lord Strepp bowed until he almost knocked his forehead on thefloor. "You are most amiable, Mr. O'Ruddy. You of course will give methe name of some friend to whom I can refer minor matters?"

I found that I could lie in England as readily as ever I did inIreland. "My friend will be on the ground with me, my lord; and as healso is a very amiable man it will not take two minutes to makeeverything clear and fair." Me, with not a friend in the world butFather O'Donovan and Mickey Clancy at Glandore!

Lord Strepp bowed again, the same as before. "Until the morning then,Mr. O'Ruddy," he said, and left me.

I sat me down on my bed to think. In truth I was much puzzled andamazed. These gentlemen were actually reasonable and were behavinglike men of heart. Neither my books nor my father's stories--greatlies, many of them, God rest him!--had taught me that the duellinggentry could think at all, and I was quite certain that they nevertried. "You were looking at me, sir?" "Was I, 'faith? Well, if I careto look at you I shall look at you." And then away they would go atit, prodding at each other's bellies until somebody's flesh swalloweda foot of steel. "Sir, I do not like the colour of your coat!" Clash!"Sir, red hair always offends me." Cling! "Sir, your fondness forrabbit-pie is not polite." Clang!

However, the minds of young Lord Strepp and Colonel Royale seemed tobe capable of a process which may be termed human reflection. It wasplain that the Colonel did not like the situation at all, and perhapsconsidered himself the victim of a peculiarly exasperating combinationof circumstances. That an Irishman should turn up in Bristol and givehim the lie over a French pair of breeches must have seemedastonishing to him, notably when he learned that the Irishman wasquite correct, having in fact a clear title to speak authoritativelyupon the matter of the breeches. And when Lord Strepp learned that Iwas The O'Ruddy he saw clearly that the Colonel was in the wrong, andthat I had a perfect right to resent the insult to my father's memory.And so the Colonel probably said: "Look you, Strepp. I have no desireto kill this young gentleman, because I insulted his father's name. Itis out of all decency. And do you go to him this second time and seewhat may be done in the matter of avoidance. But, mark you, if heexpresses any wishes, you of course offer immediate accommodation. Iwill not wrong him twice." And so up came my Lord Strepp and hemmedand hawed in that way which puzzled me. A pair of thoughtful,honourable fellows, these, and I admired them greatly.

There was now no reason why I should keep my chamber, since if I nowmet even the Colonel himself there would be no brawling; only bows. Iwas not, indeed, fond of these latter,--replying to Lord Strepp hadalmost broken my back; but, any how, more bows were better than moreloud words and another downpour of waiters and pot-boys.

But I had reckoned without the dark-skinned man, Forister. When Iarrived in the lower corridor and was passing through it on my way totake the air, I found a large group of excited people talking of thequarrel and the duel that was to be fought at daybreak. I thought itwas a great hubbub over a very small thing, but it seems that themainspring of the excitement was the tongue of this black Forister."Why, the Irish run naked through their native forests," he wascrying. "Their sole weapon is the great knotted club, with which,however, they do not hesitate, when in great numbers, to attack lionsand tigers. But how can this barbarian face the sword of an officer ofHis Majesty's army?"

Some in the group espied my approach, and there was a nudging ofelbows. There was a general display of agitation, and I marvelled atthe way in which many made it to appear that they had not formed partof the group at all. Only Forister was cool and insolent. He staredfull at me and grinned, showing very white teeth. "Swords are verydifferent from clubs, great knotted clubs," he said with admirabledeliberation.

"Even so," rejoined I gravely. "Swords are for gentlemen, while clubsare to clout the heads of rogues--thus." I boxed his ear with my openhand, so that he fell against the wall. "I will now picture also theuse of boots by kicking you into the inn yard which is adjacent." Sosaying I hurled him to the great front door which stood open, andthen, taking a sort of hop and skip, I kicked for glory and theSaints.

I do not know that I ever kicked a man with more success. He shot outas if he had been heaved by a catapult. There was a dreadful uproarbehind

me, and I expected every moment to be stormed by thewaiter-and-pot-boy regiment. However I could hear some of thegentlemen bystanding cry:

"Well done! Well kicked! A record! A miracle!"

But my first hours on English soil contained still other festivities.Bright light streamed out from the great door, and I could plainlynote what I shall call the arc or arcs described by Forister. Hestruck the railing once, but spun off it, and to my great astonishmentwent headlong and slap-crash into some sort of an upper servant whohad been approaching the door with both arms loaded with cloaks,cushions, and rugs.

I suppose the poor man thought that black doom had fallen upon himfrom the sky. He gave a great howl as he, Forister, the cloaks,cushions, and rugs spread out grandly in one sublime confusion.

Some ladies screamed, and a bold commanding voice said: "In thedevil's name what have we here?" Behind the unhappy servant had beencoming two ladies and a very tall gentleman in a black cloak thatreached to his heels. "What have we here?" again cried this tall man,who looked like an old eagle. He stepped up to me haughtily. I knewthat I was face to face with the Earl of Westport.

But was I a man for ever in the wrong that I should always be givingdown and walking away with my tail between my legs? Not I; I stoodbravely to the Earl:

"If your lordship pleases, 'tis The O'Ruddy kicking a blackguard intothe yard," I made answer coolly.

I could see that he had been about to shout for the landlord and morewaiters and pot-boys, but at my naming myself he gave a quick stare.

"The O'Ruddy?" he repeated. "Rubbish!"

He was startled, bewildered; but I could not tell if he were glad orgrieved.

"'Tis all the name I own," I said placidly. "My father left it meclear, it being something that he could not mortgage. 'Twas on hisdeath-bed he told me of lending you the breeches, and that is why Ikicked the man into the yard; and if your lordship had arrived soonerI could have avoided this duel at daybreak, and, any how, I wonder athis breeches fitting you. He was a small man."

Suddenly the Earl raised his hand. "Enough," he said sternly. "You areyour father's son. Come to my chamber in the morning, O'Ruddy."

There had been little chance to see what was inside the cloaks of theladies, but at the words of the Earl there peeped from one hood a pairof bright liquid eyes--God save us all! In a flash I was no longer afree man; I was a dazed slave; the Saints be good to us!

The contents of the other hood could not have been so interesting, forfrom it came the raucous voice of a bargeman with a cold:

"Why did he kick him? Whom did he kick? Had he cheated at play? Wherehas he gone?"

The upper servant appeared, much battered and holding his encrimsonednose.

"My lord--" he began.

But the Earl roared at him,--

"Hold your tongue, rascal, and in future look where you are going anddon't get in a gentleman's way."

The landlord, in a perfect anguish, was hovering with his squadrons onthe flanks. They could not think of pouncing upon me if I was noticedat all by the great Earl; but, somewhat as a precaution perhaps, theyremained in form for attack. I had no wish that the pair of brighteyes should see me buried under a heap of these wretches, so I bowedlow to the ladies and to the Earl and passed out of doors. As I left,the Earl moved his hand to signify that he was now willing to endurethe attendance of the landlord and his people, and in a moment the innrang with hurried cries and rushing feet.

As I passed near the taproom window the light fell full upon arailing; just beneath and over this railing hung two men. At first Ithought they were ill, but upon passing near I learned that they weresimply limp and helpless with laughter, the sound of which theycontrived to keep muffled. To my surprise I recognized the persons ofyoung Lord Strepp and Colonel Royale.