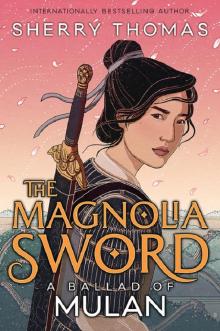

The Magnolia Sword

Sherry Thomas

First published by Allen & Unwin in 2019

Text copyright © Sherry Thomas 2019

Cover illustration copyright © Christina Chung 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76087 668 5

eISBN 9781760872267

For teaching resources, explore www.allenandunwin.com/resources/for-teachers

Book design by Neil Swaab

Set by ElfElm Publishing

Vector illustration by TopGear / Shutterstock.com

www.sherrythomas.com

To X, only the best for you and this is definitely one of my best

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

EPILOGUE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

NOTES ON LANGUAGE AND HISTORICAL MISCELLANY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

“Hua xiong-di, it has been a while,” my opponent murmurs. In the feeble light, his shadow is long, menacing.

It has been nearly two years since we last crossed swords.

But I am nobody’s xiong-di. Nobody’s younger brother.

“Time passes like water,” I reply, drawing a shallow breath. “Have you been well, Nameless xiong?”

In those notes of his that somehow find their way into my hands, he has always referred to himself as the Humble Nameless. But I know who he is. I knew the moment I first laid eyes on his sword-lean, sword-sharp handwriting.

The one against whom I am fated to clash.

My hand tightens around the hilt of my blade—not the priceless family heirloom that lies at the root of the enmity between us, but only a bronze practice sword of identical length and weight.

“Hua xiong-di’s swordsmanship must have improved greatly since our last meeting.”

My opponent keeps his voice low, but his words reach me clearly, despite the cloth that covers the lower half of his face. A shrieking wind flaps its corner, just below his chin. We are three days past the Lantern Festival, which marks the end of New Year celebrations. In the South, the first stirrings of spring must already be felt, a warmth in the breeze, a softening underfoot. But here in the North, the air is as frozen as the ground on which I stand.

I exhale, my breath vaporous. “Nameless xiong will have, of course, improved even more.”

It is the polite response—and my deepest fear. The two previous times we met, I held my own. But things have changed since my family’s abrupt flight to the North. My training conditions have deteriorated; it will be a wonder if my swordsmanship hasn’t.

“Hua xiong-di is too generous in his praise,” says my opponent. “Time flees. Shall we?”

My insides twist. Icy wind scrapes my cheeks. A bead of perspiration trickles down my spine, leaving behind a damp, cold trail.

This is not the real battle, I remind myself. Our actual duel will take place next month, on a date set when I was still an infant. This is only an interim assessment, a test of my readiness—and his.

I incline my head. “Nameless xiong, please.”

I am ceding him the opening strike. He is the one who arranges these predawn meetings, but I am, so to speak, the host, as our combats always take place near my home. I have, however, never been to this spot, a small hillside clearing next to a decrepit shrine, where two incongruously new lanterns hang before the battered gate. And he occupies the slight rise that I would have taken, had I arrived first.

All the same, etiquette must be observed.

My opponent salutes me with proper decorum and respect. I return the gesture. Those of us trained in the way of martial arts like to cloak our violence with as much ceremony as possible.

But in truth I don’t mind observing the rules for men. They get to concern themselves with how things should be done, while women must comply with everything that isn’t allowed.

We draw our swords, my blade leaving its casing with a soft metallic hiss. My stomach clenches again, but my hand is steady. I know this sword. I know what to do with it. I inhale, a measured intake of air, followed by an equally deliberate release.

He too breathes deeply, quietly. Above the cloth that conceals the rest of his features, his eyes are shadowed. Only the blade of his sword catches the scant light, a dangerous gleam in the darkest hour.

I have long wondered whether I would recognize him if I saw him elsewhere, without sword, without disguise. Sometimes strangers of similar height and build snag my attention and I find myself studying them. But I always know they aren’t him—they lack his aura of deadliness.

His silence and stillness flood my awareness: I have been waiting for this day, for his abrupt return.

The moment he advances, I launch forward to slip past him to the higher ground beyond. But he sees through my feint and slashes toward my midsection. I point my blade at his left shoulder, forcing him to his right while pushing aside his attack with my scabbard. When his blade hits the scabbard, however, my heart recoils. That sound—it isn’t an ordinary weapon glancing off wood and leather, but an extremely sharp edge cutting into my scabbard.

He is wielding Sky Blade, one of the pair of legendary swords our families have fought over for generations.

When our weapons meet at last, Sky Blade immediately notches my practice sword. The sensation jars my palm. I wheel around and attack his left shoulder again. “Yuan xiong is impatient to bring Sky Blade.”

I use his real surname deliberately. There is little point in continuing to address him as Brother Nameless when he has shown me something that identifies him so plainly.

“With the duel so near, I’m surprised Hua xiong-di did not bring Heart Sea,” he says.

What can I say? That I don’t have access to Sky Blade’s mate? That my father still hasn’t entrusted it to me?

“Swordsmanship isn’t about swords, but strength of will.” I repeat what Father has told me many times.

When two opponents are equal in skill and weaponry, strength of will comes into play. But when his is a legendary sword and mine no more legendary than Auntie Xia’s meat cleaver …

We exchange a flurry of strikes. Since my family arrived in the North, I haven’t had a regular practice partner. Occasionally a friend of Father’s passes through and works with me; still, I’ve grown rusty.

But as the match intensifies, my reflexes quicken. My footwork becomes more agile, my mind sharper and more focused. And with this engrossment comes a palpable pleasure: If I let everything else fall away, if I concentrate on only the physical aspect of our contest, then I can’t help but delight in it. I love fighting well and he has challenged me to fight better th

an I ever have before. A lifetime of training flows through my sinews to produce a dexterity and lightness that would impress even Father.

But I can’t let everything else fall away—I can never forget that what happened to Father could befall me too. And my opponent hasn’t traveled goodness knows what distance to spar with me for fun. He is seeking my weaknesses.

I am tall; my height exceeds that of the average man, or at least that of the average man in the South. As a result of my training, I also possess considerable strength. But Yuan Kai has trained as much as I have—more, most likely, since he’s older. And he’s half a head taller, the width of his shoulders unmistakable even in the meager light.

Our contest must not become one of strength. Only in swordsmanship will I have any hope of besting him.

Since he’s unwilling to give up his higher spot, I retreat slowly until we are on flat ground at the foot of the incline. Then I change tactics: Whenever I get a chance, I aim my blade at his knees, disrupting his footwork and destabilizing his balance.

Once, he almost stumbles, but rights himself and retaliates with a dangerously angled jab at my throat.

I leap backward. He advances, suddenly a lot more aggressive. He is steering me toward the half-dilapidated outer wall of the shrine. With my back to the wall, I will need to rely on strength rather than speed or cunning—exactly what I’ve been trying to avoid.

Somehow I am only one stride away from the wall. His blade is a blur of deadly edges, sealing me in place. With a shrill scrape our swords brace together, jolting my shoulders. I usually fight single-handed, but now I have both hands on the hilt, and even so he is slowly, inexorably pushing my blade inward, bearing down on me like a falling sky.

I scoot my right foot back half a step to gain better leverage. All the same, my arms tremble. My sword slants at an almost unsalvageable angle: If I allow my elbows to bend, I will not be able to straighten them again. But I also cannot hold out much longer, and I cannot move back any farther without being trapped against the waist-high wall.

We stare at each other. The wind howls. The flimsy light jerks with the violent swings of the lanterns. I can read nothing in his eyes, dark and becoming darker, but a blank intensity that makes my breath emerge with a sound halfway between a gasp and a sob. My entire body shakes with the effort of holding him back.

I yank my sword toward myself, dodging just in time as he staggers forward, unbalanced. He seems about to crash into the decaying wall. But with a hard slam of his free hand against the masonry, he vaults himself into a sideways somersault.

I leap to the top of the wall. As he lands on his feet, I dive from my perch and strike from above. He meets my blade with his own. I pivot as soon as I touch ground so he won’t be able to trap me again.

He does not immediately attack. Three paces apart, we circle each other, our blades gleaming coldly.

Patience, Father has always counseled. Patience and concentration.

I don’t find it difficult to concentrate when there is something to concentrate on—a weapon lashing my way always has my undivided attention. But in a lull my focus splinters. My ears listen to his footsteps to gauge whether he walks more quietly than I do. My gaze flickers over his clothes—what can their style and construction tell me? My fingers flex and tighten around the handle of my sword, and I’m again envious that he can carry his priceless blade into combat and I’m not allowed to use mine even at home.

“Hua xiong-di’s footwork has improved,” he declares softly.

My eyes narrow. He hasn’t exactly paid me a compliment, as

I had to rely on footwork to get out of an undesirable position.

“Yuan xiong’s strength has also improved,” I retort.

That is practically an insult, to comment on a swordsman’s vigor rather than his skill.

He laughs. “It will be an epic battle, won’t it, our duel?”

Father has taught me that I should feel only utmost vigilance toward the duel. But each time I’ve met Yuan Kai, beneath my trepidation, there has been a … thrill—as if some part of me wants a contest that lasts luxuriously, from dawn to dusk.

I spring and attack, my jabs quick and just a little agitated. I can’t be sure, but I seem to have caught him off guard. He parries, but his blade meets mine a fraction of a second too late each time. If I were fighting like that, Father would have sharp words for me. In fact, I find myself tempted to tell Yuan Kai to do better.

Our swords brace. The previous time, he applied overwhelming force; now, just enough to ensure that I don’t hack into him. We stand toe to toe, nothing but crossed blades between us.

He studies me—not my technique, but my face, as if he has forgotten the precise arrangement of my features. As if he would rather look at me than fight me.

I would rather look at him too—preferably with his face uncovered.

I think of him constantly. And when I do, it is often accompanied by a sharp pinch in my heart, a pang of loss. For what, I don’t know, because we are only opponents and we can only be opponents. But sometimes my thoughts run away with me, and in my daydreams we roam the shores of Lake Tai in spring, as peach blossoms drift onto our path. Sometimes we even sit on the bow of a small boat and glide across the lake, under the golden and crimson sky of a summer sunset.

In my daydreams, the duel does not mark the last time I will ever see him.

Does the frail, flickering light seem to trace a line across his forehead? Is that a crease of concentration—or a scar? If it is a scar, how did he come by it in that perilous spot?

With a start, I realize I have lifted my other hand, as if I intend to touch that perhaps-scar. Our eyes meet again. He does not look away, and neither do I.

A gust roars past. The lanterns gutter, once, twice—and extinguish. The near-dawn plunges back into darkness.

We leap apart as if we’ve been caught in something illicit.

I inhale slowly. His indrawn breath too is carefully even. Silence spreads, broken only by the restless wind, bumping lanterns into gateposts and rattling the roof tiles that still remain on the shrine. In the distance, the Northern town that serves as my new home is almost uniformly dark, with only a few lit windows. And the city gate won’t open for at least the time of a meal.

Abruptly he says, “I take my leave of Hua xiong-di.”

I exhale. But my relief at not having lost to him is immediately superseded by the questions that always plague me at his visits. Does he have his family’s permission to seek me out? How is it that he can find me, South or North? And why did he visit me twice in quick succession, making me believe that we would see each other regularly, and then disappear for almost two years—only to reemerge now, little more than a month before the duel?

“Yuan xiong must excuse me for not escorting him farther along his path,” I reply, back to courtesy and politesse. “I trust we will meet again.”

We sheathe our swords and salute each other. He walks to his horse, pins on a cloak, and mounts, his motion easy, fluid.

From atop his steed, he murmurs, “A shame, isn’t it?”

I frown. “What’s a shame?”

“That we were born into this rivalry.” He gazes at me. “Had we met under different circumstances, we could have been … friends.”

And then he is off, his cloak streaming behind him, a great wind-whipped shadow.

Half a month later

Only seven left.

I am to catch forty-nine pebbles Father fires at me, hit forty-nine targets he indicates around the courtyard, and intercept forty-nine projectiles in midair with projectiles of my own. All while blindfolded.

Father sets these exercises because the Hua family produces not only sword masters, but also experts in hidden weaponry, who can capture and deploy small flying objects under almost any circumstance. Today I have finished the first two sets without mistakes. Only seven are left in the third set, and I will have achieved a perfect record, which I haven’t managed in a year

and a half.

Of course Father makes me wait now.

Patience, I tell myself. Concentration. Don’t let your attention wander.

Murong, my little brother, jumps in place to keep warm—whenever I practice hidden weaponry, it’s his chore to pick up all the small objects that end up on the ground, and he is even more impatient than I am with Father’s deliberate pause. In the kitchen, Auntie Xia’s cleaver falls rhythmically on a wooden board. This morning Father started my practice late, or I’d be helping her. A cold wind skitters through, carrying with it the aroma of frying dough and the soft whimpering of a baby from several courtyards away.

Beneath it all, I hear the odd quietness in the marketplace, when it should be boisterous with bargaining shoppers and poultry in woven cages, clucking and quacking.

I wonder how Father will react if I manage to intercept the last seven remaining projectiles. The first time I accomplished a perfect record, I wept in euphoria and sheer relief. He said, Let’s see how long it will be before you do it again. And when I succeeded again, after two years, he only said, Took you long enough.

Does Yuan Kai train with a similar rigor? How does he get away from home long enough to find me? Father doesn’t like me to go anywhere by myself—even dressed as a man—for more than half a day.

Stop thinking. Practice isn’t over yet. Listen!

I shuffle the small, soft projectiles I hold, four in my left hand, three in my right.

The air sings—Father has released his remaining projectiles at once. I launch all seven of mine, also in a single motion.

“You got them, jiejie!” cries Murong.

I already know—I heard seven soft collisions—and can’t help a small smile. I don’t always love my training, but I love what that training enables me to do. Today, it has facilitated perfection.

I undo my blindfold to the sight of our courtyard littered with tiny grain sacks, and Murong busy gathering them into a basket.

When we lived in the South, our house on Lake Tai was set apart, its spacious grounds enclosed by high walls topped with glazed tiles. Then it didn’t matter what weapons I used or how much noise I made. But here in the North we’ve had to adjust our training methods. In theory, we still have our own home. But it’s a small courtyard dwelling packed together with other similar courtyards, the alleys in between narrower than my wingspan.