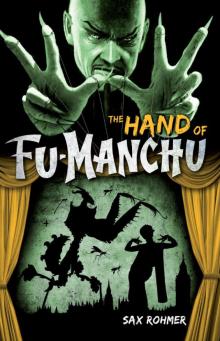

The Hand of Dr. Fu Manchu

Sax Rohmer

“The true king of the pulp mystery is Sax Rohmer—and the shining ruby in his crown is without a doubt his Fu-Manchu stories.” —James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Colony

“Fu-Manchu remains the definitive diabolical mastermind of the 20th Century. Though the arch-villain is ‘the Yellow Peril incarnate,’ Rohmer shows an interest in other cultures and allows his protagonist a complex set of motivations and a code of honor which often make him seem a better man than his Western antagonists. At their best, these books are very superior pulp fiction... at their worst, they’re still gruesomely readable.” —Kim Newman, award-winning author of Anno Dracula

“I grew up reading Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels, in cheap paperback editions with appropriately lurid covers. They completely entranced me with their vision of a world constantly simmering with intrigue and wildly overheated ambitions. Even without all the exotic detail supplied by Rohmer’s imagination, I knew full well that world wasn’t the same as the one I lived in... For that alone, I’m grateful for all the hours I spent chasing around with Nayland Smith and his stalwart associates, though really my heart was always on their intimidating opponent’s side.”—K. W. Jeter, acclaimed author of Infernal Devices

“Sax Rohmer is one of the great thriller writers of all time! Rohmer created in Fu-Manchu the model for the super-villains of James Bond, and his hero Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie are worthy stand-ins for Holmes and Watson... though Fu-Manchu makes Professor Moriarty seem an under-achiever.” —Max Allan Collins, New York Times bestselling author of The Road to Perdition

“I love Fu-Manchu, the way you can only love the really GREAT villains. Though I read these books years ago he is still with me, living somewhere deep down in my guts, between Professor Moriarty and Dracula, plotting some wonderfully hideous revenge against an unsuspecting mankind.”—Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

“Fu-Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant. Discover him if you dare!” —Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships

THE COMPLETE FU-MANCHU SERIES BY SAX ROHMER

Available now from Titan Books:

THE MYSTERY OF DR. FU-MANCHU

Coming soon from Titan Books:

THE HAND OF FU-MANCHU

DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU

THE MASK OF FU-MANCHU

THE BRIDE OF FU-MANCHU

THE TRAIL OF FU-MANCHU

PRESIDENT FU-MANCHU

THE DRUMS OF FU-MANCHU

THE ISLAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE SHADOW OF FU-MANCHU

RE-ENTER FU-MANCHU

EMPEROR FU-MANCHU

THE WRATH OF FU-MANCHU AND OTHER STORIES

THE HAND OF

DR. FU-MANCHU

SAX ROHMER

TITAN BOOKS

THE HAND OF FU-MANCHU

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686053

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686718

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St London SE1 0UP

First edition: May 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First published as a novel in the UK as The Si-Fan Mysteries, Methuen, 1917

First published as a novel in the US as The Hand of Fu-Manchu, McBride, 1917

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2012 The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

Frontispiece illustration by J. C. Coll, detail from an illustration for “The Clue of the Pigtail”, first appearing in Collier’s Weekly, March 1, 1913. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Knapp for the illustrations as they appeared on “The Page of Fu-Manchu” – http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United States.

CONTENTS

Chapter One: The Traveler from Tibet

Chapter Two: The Man With the Limp

Chapter Three: “Sâkya Mûni”

Chapter Four: The Flower of Silence

Chapter Five: John Ki’s

Chapter Six: The Si-Fan Move

Chapter Seven: Chinatown

Chapter Eight: Zarmi of the Joy-Shop

Chapter Nine: Fu-Manchu

Chapter Ten: The Tûlun-Nûr Chest

Chapter Eleven: In the Fog

Chapter Twelve: The Visitant

Chapter Thirteen: The Room Below

Chapter Fourteen: The Golden Pomegranates

Chapter Fifteen: Zarmi Reappears

Chapter Sixteen: I Track Zarmi

Chapter Seventeen: I Meet Dr. Fu-Manchu

Chapter Eighteen: Queen of Hearts

Chapter Nineteen: “Zagazig”

Chapter Twenty: The Note on the Door

Chapter Twenty-One: The Second Message

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Secret of the Wharf

Chapter Twenty-Three: Arrest of Samarkan

Chapter Twenty-Four: Café de l’Egypte

Chapter Twenty-Five: The House of Hashish

Chapter Twenty-Six: “The Demon’s Self”

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Room With the Golden Door

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Mandarin Ki-Ming

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Lama Sorcery

Chapter Thirty: Medusa

Chapter Thirty-One: The Marmoset

Chapter Thirty-Two: Shrine of Seven Lamps

Chapter Thirty-Three: An Anti-Climax

Chapter Thirty-Four: Graywater Park

Chapter Thirty-Five: The East Tower

Chapter Thirty-Six: The Dungeon

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Three Nights Later

Chapter Thirty-Eight: The Monk’s Plan

Chapter Thirty-Nine: The Shadow Army

Chapter Forty: The Black Chapel

About the Author

“I looked into that still, awful face, into those unnatural green eyes.”

CHAPTER ONE

THE TRAVELER FROM TIBET

“Who’s there?” I called sharply.

I turned and looked across the room. The window had been widely opened when I entered, and a faint fog haze hung in the apartment, seeming to veil the light of the shaded lamp. I watched the closed door intently, expecting every moment to see the knob turn. But nothing happened.

“Who’s there?” I cried again, and, crossing the room, I threw open the door.

The long corridor without, lighted only by one inhospitable lamp at a remote end, showed choked and yellowed with

this same fog so characteristic of London in November. But nothing moved to right nor left of me. The New Louvre Hotel was in some respects yet incomplete, and the long passage in which I stood, despite its marble facings, had no air of comfort or good cheer; palatial it was, but inhospitable.

I returned to the room, reclosing the door behind me, then for some five minutes or more I stood listening for a repetition of that mysterious sound, as of something that both dragged and tapped, which already had arrested my attention. My vigilance went unrewarded. I had closed the window to exclude the yellow mist, but subconsciously I was aware of its encircling presence, walling me in, and now I found myself in such a silence as I had known in deserts but could scarce have deemed possible in fog-bound London, in the heart of the world’s metropolis, with the traffic of the Strand below me upon one side and the restless life of the river upon the other.

It was easy to conclude that I had been mistaken, that my nervous system was somewhat overwrought as a result of my hurried return from Cairo—from Cairo where I had left behind me many a fondly cherished hope. I addressed myself again to the task of unpacking my steamer-trunk and was so engaged when again a sound in the corridor outside brought me upright with a jerk.

A quick footstep approached the door, and there came a muffled rapping upon the panel.

This time I asked no question, but leapt across the room and threw the door open. Nayland Smith stood before me, muffled up in a heavy traveling coat, and with his hat pulled down over his brows.

“At last!” I cried, as my friend stepped in and quickly reclosed the door.

Smith threw his hat upon the settee, stripped off the great-coat, and pulling out his pipe began to load it in feverish haste.

“Well,” I said, standing amid the litter cast out from the trunk, and watching him eagerly, “what’s afoot?”

Nayland Smith lighted his pipe, carelessly dropping the match-end upon the floor at his feet.

“God knows what is afoot this time, Petrie!” he replied. “You and I have lived no commonplace lives; Dr. Fu-Manchu has seen to that; but if I am to believe what the Chief has told me today, even stranger things are ahead of us!”

I stared at him wonder-stricken.

“That is almost incredible,” I said; “terror can have no darker meaning than that which Dr. Fu-Manchu gave to it. Fu-Manchu is dead, so what have we to fear?”

“We have to fear,” replied Smith, throwing himself into a corner of the settee, “the Si-Fan!”

I continued to stare, uncomprehendingly.

“The Si-Fan—”

“I always knew and you always knew,” interrupted Smith in his short, decisive manner, “that Fu-Manchu, genius that he was, remained nevertheless the servant of another or others. He was not the head of that organization which dealt in wholesale murder, which aimed at upsetting the balance of the world. I even knew the name of one, a certain mandarin, and member of the Sublime Order of the White Peacock, who was his immediate superior. I had never dared to guess at the identity of what I may term the Head Center.”

He ceased speaking, and sat gripping his pipe grimly between his teeth, whilst I stood staring at him almost fatuously. Then—

“Evidently you have much to tell me,” I said, with forced calm.

I drew up a chair beside the settee and was about to sit down.

“Suppose you bolt the door,” jerked my friend.

I nodded, entirely comprehending, crossed the room and shot the little nickel bolt into its socket.

“Now,” said Smith as I took my seat, “the story is a fragmentary one in which there are many gaps. Let us see what we know. It seems that the despatch which led to my sudden recall (and incidentally yours) from Egypt to London and which only reached me as I was on the point of embarking at Suez for Rangoon, was prompted by the arrival here of Sir Gregory Hale, whilom attaché at the British Embassy, Peking. So much, you will remember, was conveyed in my instructions.”

“Quite so.”

“Furthermore, I was instructed, you’ll remember, to put up at the New Louvre Hotel; therefore you came here and engaged this suite whilst I reported to the chief. A stranger business is before us, Petrie, I verily believe, than any we have known hitherto. In the first place, Sir Gregory Hale is here—”

“Here?”

“In the New Louvre Hotel. I ascertained on the way up, but not by direct inquiry, that he occupies a suite similar to this, and incidentally on the same floor.”

“His report to the India Office, whatever its nature, must have been a sensational one.”

“He has made no report to the India Office.”

“What! made no report?”

“He has not entered any office whatever, nor will he receive any representative. He’s been playing at Robinson Crusoe in a private suite here for close upon a fortnight—id est since the time of his arrival in London!”

I suppose my growing perplexity was plainly visible, for Smith suddenly burst out with his short, boyish laugh.

“Oh! I told you it was a strange business,” he cried.

“Is he mad?”

Nayland Smith’s gaiety left him; he became suddenly stern and grim.

“Either mad, Petrie, stark raving mad, or the savior of the Indian Empire—perhaps of all Western civilization. Listen. Sir Gregory Hale, whom I know slightly and who honors me, apparently, with a belief that I am the only man in Europe worthy of his confidence, resigned his appointment at Peking some time ago, and set out upon a private expedition to the Mongolian frontier with the avowed intention of visiting some place in the Gobi Desert. From the time that he actually crossed the frontier he disappeared for nearly six months, to reappear again suddenly and dramatically in London. He buried himself in this hotel, refusing all visitors and only advising the authorities of his return by telephone. He demanded that I should be sent to see him; and—despite his eccentric methods—so great is the Chief’s faith in Sir Gregory’s knowledge of matters Far Eastern, that behold, here I am.”

He broke off abruptly and sat in an attitude of tense listening. Then—

“Do you hear anything, Petrie?” he rapped.

“A sort of tapping?” I inquired, listening intently myself the while.

Smith nodded his head rapidly.

We both listened for some time, Smith with his head bent slightly forward and his pipe held in his hands; I with my gaze upon the bolted door. A faint mist still hung in the room, and once I thought I detected a slight sound from the bedroom beyond, which was in darkness. Smith noted me turn my head, and for a moment the pair of us stared into the gap of the doorway. But the silence was complete.

“You have told me neither much nor little, Smith,” I said, resuming for some reason, in a hushed voice. “Who or what is this Si-Fan at whose existence you hint?”

Nayland Smith smiled grimly.

“Possibly the real and hitherto unsolved riddle of Tibet, Petrie,” he replied—“a mystery concealed from the world behind the veil of Lamaism.” He stood up abruptly, glancing at a scrap of paper which he took from his pocket—“Suite Number 14a,” he said. “Come along! We have not a moment to waste. Let us make our presence known to Sir Gregory—the man who has dared to raise that veil.”

CHAPTER TWO

THE MAN WITH THE LIMP

“Lock the door!” said Smith significantly, as we stepped into the corridor.

I did so and had turned to join my friend when, to the accompaniment of a sort of hysterical muttering, a door further along, and on the opposite side of the corridor, was suddenly thrown open, and a man whose face showed ghastly white in the light of the solitary lamp beyond, literally hurled himself out. He perceived Smith and myself immediately. Throwing one glance back over his shoulder he came tottering forward to meet us.

“My God! I can’t stand it any longer!” he babbled, and threw himself upon Smith, who was foremost, clutching pitifully at him for support. “Come and see him, sir—for Heaven’s sake come in! I think he

’s dying; and he’s going mad. I never disobeyed an order in my life before, but I can’t help myself—I can’t help myself!”

“Brace up!” I cried, seizing him by the shoulders as, still clutching at Nayland Smith, he turned his ghastly face to me. “Who are you, and what’s your trouble?”

“I’m Beeton, Sir Gregory Hale’s man.”

Smith started visibly, and his gaunt, tanned face seemed to me to have grown perceptively paler.

“Come on, Petrie!” he snapped. “There’s some devilry here.”

Thrusting Beeton aside he rushed in at the open door—upon which, as I followed him, I had time to note the number, 14a. It communicated with a suite of rooms almost identical with our own. The sitting-room was empty and in the utmost disorder, but from the direction of the principal bedroom came a most horrible mumbling and gurgling sound—a sound utterly indescribable. For one instant we hesitated at the threshold—hesitated to face the horror beyond; then almost side by side we came into the bedroom....

Only one of the two lamps was alight—that above the bed; and on the bed a man lay writhing. He was incredibly gaunt, so that the suit of tropical twill which he wore hung upon him in folds, showing if such evidence were necessary, how terribly he was fallen away from his constitutional habit. He wore a beard of at least ten days’ growth, which served to accentuate the cavitous hollowness of his face. His eyes seemed starting from their sockets as he lay upon his back uttering inarticulate sounds and plucking with skinny fingers at his lips.

Smith bent forward peering into the wasted face; and then started back with a suppressed cry.

“Merciful God! can it be Hale?” he muttered. “What does it mean? what does it mean?”

I ran to the opposite side of the bed, and placing my arms under the writhing man, raised him and propped a pillow at his back. He continued to babble, rolling his eyes from side to side hideously; then by degrees they seemed to become less glazed, and a light of returning sanity entered them. They became fixed; and they were fixed upon Nayland Smith, who bending over the bed, was watching Sir Gregory (for Sir Gregory I concluded this pitiable wreck to be) with an expression upon his face compound of many emotions.