Daughter of Fu-Manchu

Sax Rohmer

“Without Fu-Manchu we wouldn’t have Dr. No, Doctor Doom or Dr. Evil. Sax Rohmer created the first truly great evil mastermind. Devious, inventive, complex, and fascinating. These novels inspired a century of great thrillers!”

Jonathan Maberry, New York Times bestselling author of Assassin’s Code and Patient Zero

“The true king of the pulp mystery is Sax Rohmer—and the shining ruby in his crown is without a doubt his Fu-Manchu stories.”

James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Colony

“Fu-Manchu remains the definitive diabolical mastermind of the 20th Century. Though the arch-villain is ‘the Yellow Peril incarnate,’ Rohmer shows an interest in other cultures and allows his protagonist a complex set of motivations and a code of honor which often make him seem a better man than his Western antagonists. At their best, these books are very superior pulp fiction… at their worst, they’re still gruesomely readable.”

Kim Newman, award-winning author of Anno Dracula

“Sax Rohmer is one of the great thriller writers of all time! Rohmer created in Fu-Manchu the model for the super-villains of James Bond, and his hero Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie are worthy stand-ins for Holmes and Watson… though Fu-Manchu makes Professor Moriarty seem an under-achiever.”

Max Allan Collins, New York Times bestselling author of The Road to Perdition

“I grew up reading Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels, in cheap paperback editions with appropriately lurid covers. They completely entranced me with their vision of a world constantly simmering with intrigue and wildly overheated ambitions. Even without all the exotic detail supplied by Rohmer’s imagination, I knew full well that world wasn’t the same as the one I lived in… For that alone, I’m grateful for all the hours I spent chasing around with Nayland Smith and his stalwart associates, though really my heart was always on their intimidating opponent’s side.”

K. W. Jeter, acclaimed author of Infernal Devices

“A sterling example of the classic adventure story, full of excitement and intrigue. Fu-Manchu is up there with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and Zorro—or more precisely with Professor Moriarty, Captain Nemo, Darth Vader, and Lex Luthor—in the imaginations of generations of readers and moviegoers.”

Charles Ardai, award-winning novelist and founder of Hard Case Crime

“I love Fu-Manchu, the way you can only love the really GREAT villains. Though I read these books years ago he is still with me, living somewhere deep down in my guts, between Professor Moriarty and Dracula, plotting some wonderfully hideous revenge against an unsuspecting mankind.”

Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

“Fu-Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant. Discover him if you dare!”

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships

THE COMPLETE FU-MANCHU SERIES

BY SAX ROHMER

Available now from Titan Books:

THE MYSTERY OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE RETURN OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE HAND OF FU-MANCHU

Coming soon from Titan Books:

THE MASK OF FU-MANCHU

THE BRIDE OF FU-MANCHU

THE TRAIL OF FU-MANCHU

PRESIDENT FU-MANCHU

THE DRUMS OF FU-MANCHU

THE ISLAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE SHADOW OF FU-MANCHU

RE-ENTER FU-MANCHU

EMPEROR FU-MANCHU

THE WRATH OF FU-MANCHU AND OTHER STORIES

DAUGHTER OF

FU-MANCHU

SAX ROHMER

TITAN BOOKS

DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686060

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686725

Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark St London SE1 0UP

First edition: September 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First published as a novel in the UK by William Collins & Co. Ltd, 1931 First published as a novel in the US by Doubleday, Doran, 1931

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2012 The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

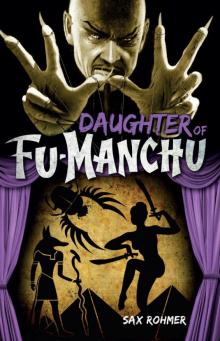

Frontispiece illustration by John Richard Flanagan, detail from an illustration for “Fu Manchu’s Daughter,” first appearing in Collier’s Weekly, May 17 1930. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Knapp for the illustrations as they appeared on “The Page of Fu-Manchu” - www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United States.

Contents

Title Page

Part One

Chapter One: The Living Death

Chapter Two: Rima

Chapter Three: Tomb of the Black Ape

Part Two

Chapter Four: Fah Lo Suee

Chapter Five: Nayland Smith Explains

Chapter Six: The Council of Seven

Part Three

Chapter Seven: Kâli

Chapter Eight: Swâzi Pasha Arrives

Chapter Nine: The Man from El-Khârga

Part Four

Chapter Ten: Abbots Hold

Chapter Eleven: Dr. Amber

Chapter Twelve: Loro of the Si-Fan

“She continued to watch me. I tried to hate her. But her eyes caressed me, and I was afraid—horribly afraid of this witch-woman who had the uncanny power which was Circe’s, of stealing men’s souls.”

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

THE LIVING DEATH

Just in sight of Shepheard’s I pulled up.

I believe a sense of being followed is a recognized nervous disorder. But it was one I had never experienced without finding it to be based on fact.

Certainly what had occurred was calculated to upset the stoutest nerves. To lose an old and deeply respected friend, and in the very hour of the loss to be confronted by a mystery seemingly defying natural laws, is a test of staying power which any man might shirk.

I had set out for Cairo in a frame of mind which I shall not attempt to describe. But this damnable idea that I was spied upon— followed—asserted itself in the first place on the train.

In spirit still back in camp beside the body of my poor chief, I suddenly became conscious of queer wanderers in the corridor. One yellow face in particular I had detected peering in at me, which possessed such unusual and dreadful malignity that at some point just below Beni Suef I toured the cars from end to end determined to convince myself that those oblique squint

ing eyes were not a product of my imagination. Several times I had fallen into a semi-doze, for I had had no proper sleep for forty-eight hours.

I failed to find the yellow horror. This had disturbed me, because it made me distrust myself. But it served to banish my sleepiness. Reinforced with a stiff whisky-and-soda, I stayed very widely awake as the train passed station after station in the Nile Valley and drew ever nearer to Cairo.

The squinting eyes did not reappear.

Then, having hailed a taxi outside the station, I suddenly became aware, in some quite definite way, that the watcher was following again. In sight of Shepheard’s I pulled up, dismissed the taxi, and mounted the steps to the terrace.

Tables were prepared for tea, but few as yet were occupied. I could see no one I knew, but of this I was rather glad.

Standing beside one of those large ornamental vases at the head of the steps, I craned over, looking left along Sharia Kamel. I was just in time. My trick had its reward.

A limousine driven by an Arab chauffeur passed in a flash.

But the oblique squinting eyes of its occupant stared up at the balcony. It was the man of the train. I had not been dreaming.

I think he saw me, but of this I couldn’t be sure. The car did not slacken speed and I lost sight of it at the bend by Esbekiyeh Gardens.

A white-robed, red-capped waiter approached. Mentally reviewing my condition and my needs, I ordered a pot of Arab coffee. I smoked a pipe, drank my coffee, and set out on foot for the club. Here I obtained the address I wanted…

In a quiet thoroughfare a brass plate beside a courtyard entrance confirmed its correctness. In response to my ring a Nubian servant admitted me. I was led upstairs and without any ceremony shown into a large and delightfully furnished study.

The windows opened on a balcony draped with purple blossom and overhanging the courtyard where orange trees grew. There were many books and the place was full of flowers. In its arrangement, the rugs upon the floor, the ornaments, the very setting of the big writing table, I detected the hand of a woman. And I realized more keenly than ever what a bachelor misses and the price he pays for his rather overrated freedom.

My thoughts strayed for a moment to Rima, and I wondered, as I had wondered many many times, what I could have done to offend her. I was brought back sharply when I met the glance of a pair of steady eyes regarding me from beyond the big writing table.

The man I had come to see stood up with a welcoming smile. He was definitely a handsome man, gray at the temples and well set up. His atmosphere created an odd sense of security. In fact my first impression went far to explain much that I had heard of him.

“Dr. Petrie?” I asked.

He extended his hand across the table and I grasped it.

“I’m glad you have come, Mr. Greville,” he replied. They sent me your message from the club.“ His smile vanished and his face became very stern. “Please try the armchair. Cigars in the wooden box, cigarettes in the other. Or here’s a very decent pipe mixture”— sliding his pouch across the table.

“Thanks,” I said; “a pipe, I think.”

“You are shaken up,” he went on—“naturally. May I prescribe?”

I smiled, perhaps a little ruefully.

“Not at the moment. I have been rather overdoing it on the train, trying to keep myself awake.”

I filled a pipe whilst trying to muster my ideas. Then, glancing up, I met the doctor’s steady gaze; and:

“Your news was a great shock to me,” he said. “Barton, I know, was one of your oldest friends. He was also one of mine. Tell me— I’m all anxiety to hear.”

At that I began,

“As you may have heard, Dr. Petrie, we are excavating what is known as Lafleur’s Tomb at the head of the Valley of the Kings. It’s a queer business and the dear old chief was always frightfully reticent about his aims. He was generous enough when a job was done and shared the credit more than fairly. But his sense of the dramatic made him a bit difficult. Therefore, I can’t tell you very much about it. But two days ago he shifted the quarters, barred all approaches to the excavation, and generally behaved in a way which I knew from experience to mean that we were on the verge of some big discovery.

“We have two huts, but nobody sleeps in them. We are a small party and under canvas. But all this you will see for yourself—at least, I hope I can count on you? We shall have to rush for it.”

“I am coming,” Dr. Petrie replied quietly. “It’s all arranged. God knows what use I can be. But since he wished it…”

“Some time last night,” I presently went on, “I heard, or thought I heard, the chief call me: ‘Greville! Greville!’ His voice seemed strange in some way. I fell out of bed (it was pitch dark), jumped into slippers, and groped along to his tent.”

I stopped. The reality and the horror of it stopped me. But at last:

“He was dead,” I said. “Dead in his bed. A pencil had dropped from his fingers and the scribbling block which he used for notes lay on the floor beside him.”

“One moment,” Dr. Petrie interrupted me. “You say he was dead. Was this impression confirmed afterwards?”

“Forester, our chemist,” I replied sadly, “is an M.R.-C.P. though he doesn’t practise. The chief was dead. Sir Lionel Barton—the greatest Orientalist our old country has ever produced, Dr. Petrie. And he was so alive, so vital, so keen and enthusiastic.”

“Good God!” Dr. Petrie murmured. “To what did Forester ascribe death?”

“Heart failure—a quite unsuspected weakness.”

“Unaccountable! I could have sworn the man had a heart like an ox. But I am becoming somewhat puzzled, Mr. Greville. If Forester certified death from syncope, who sent me this?”

He passed a telegram across the table. I read it in growing bewilderment:

Sir Lionel Barton suffering catalepsy. Please come first train and bring antidote if any remains.

I stared at Petrie, then:

“No one in our camp sent it!” I said.

“What!”

“I assure you. No member of our party sent this message.”

I saw that it had been delivered that morning and had been handed in at Luxor at Six A.M. I began to read it aloud in a dazed way. And, whilst I was reading, a subdued but particularly eerie cry came from the courtyard. I stopped. It startled me. But its effect upon Dr. Petrie was amazing. He sprang up as though a shot had been fired in the room and leaped towards the open window.

“What was it?” I exclaimed.

Whilst the cry had not resembled any of the many with which I was acquainted in the land where the vendor of dates, of lemonade, of water, of a score of commodities has each his separate song, yet, though weird, it was not in itself definitely horrible.

Petrie turned, and:

“Something I haven’t heard for ten years,” he replied—and I saw with concern that he had grown pale—“which I had hoped never to hear again.”

“What?”

“The signal used by a certain group of fanatics of Burma loosely known as Dacoits.”

“Dacoits? But Dacoity in Burma has been dead for a generation!”

Petrie laughed.

“I made that very statement twelve years ago,” he said. “It was untrue then. It is untrue now. Yet there isn’t a soul in the courtyard.”

And suddenly I realized that he was badly shaken. He was not the type of man who was readily unnerved, and I confess that the incident—trivial though otherwise it might have seemed— impressed me unpleasantly.

“Please God I am mistaken,” he went on, walking back to his chair—“I must have been mistaken.”

But that he was not, suddenly became manifest. The door opened and a woman came in, or rather—ran in.

I had heard men at the club rave about Dr. Petrie’s wife, but the self-chosen seclusion of her life was such that up to this present moment I had never set eyes on her. I realized now that all I had heard was short of the truth. It is fortunate that modern

man is unaffected by the Troy complex; for she was, I think, quite the most beautiful woman I had ever seen in my life. I shall not attempt to describe her, for I could only fail. But, seeing that she had not even noticed my existence, I wondered, as men will sometimes wonder, by what mystic chains Dr. Petrie held this unreally lovely creature.

She ran to him and he threw his arms about her.

“You heard it!” she whispered. “You heard it!”

“I know what you are thinking, dear,” he said. “Yes, I heard it. But after all it isn’t possible.”

He looked across, at me, and suddenly his wife seemed to realize my presence.

“This is Mr. Shan Greville,” Petrie went on, “who brings me very sad news about our old friend, Sir Lionel Barton. I didn’t mean you to know, yet. But…”

Mrs. Petrie conquered her fears and came forward to greet me.

“You are very welcome,” she said.

She spoke English with a faint fascinating accent.

“But your news—do you mean—”

Into the beautiful eyes watching me I saw the strangest expression creeping. It was questioning, doubting; fearful, analytical. And suddenly Mrs. Petrie turned from me to her husband, and:

“How did it happen?” she asked.

As she spoke the words, I thought she seemed to be listening.

Briefly, Dr. Petrie repeated what I had told him, concluding by handing his wife the mysterious telegram.

“If I may interrupt for a moment,” I said, taking out my pocket case, “Sir Lionel must have written this at the moment of his fatal seizure. You see—it tails off. It was scribbled on the block which lay beside him. It was what brought me to Cairo.”

I handed the pencilled message to Petrie. His wife bent over him as he read aloud, slowly:

“Not dead… Get Petrie… Cairo… amber… inject…”

She was facing me as he read—her husband could not see her face. But he saw the telegram slip from her fingers to the carpet.