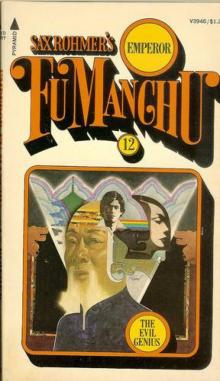

Emperor Fu Manchu f-13

Sax Rohmer

Emperor Fu Manchu

( FM - 13 )

Sax Rohmer

CHINA -- A LAND OF TONGS AND TERROR!

Adrift in the lonely rice fields of Northern China, American agent Tony McKay found himself face to face with the most diabolical evil he had ever encountered. The "Cold Men," spiritless creatures that did the unscrupulous bidding of the most dangerous secret organization on earth-- The Si Fan!

What freak of nature had caused this horrible revival of living dead? Hidden in the mountains of Communist China, the terrible leader of the Si Fan cast his web of intrigue and death. McKay would learn that where Zombies walk and murder is the law--the dead will not be still. . . such is the realm of--Fu Manchu!

Emperor Fu Manchu

by Sax Rohmer

Chapter I

“Once you pass the Second Bamboo Curtain, McKay, unless my theories are all haywire, you’ll be up against the greatest scientific criminal genius who has ever threatened the world.”

Tony McKay met the fixed regard of cold grey eyes which seemed to be sizing him up from the soles of his shoes to the crown of his head. The terse words, rapid, clipped sentences, of the remarkable man he had come to meet penetrated his brain with a bullet-like force. They registered. He knocked ash from his cigarette. The sounds and cries of a busy Chinese street reached him through an open window.

“I didn’t expect to be going to a cocktail party. Sir Denis.”

Sir Denis Nayland Smith smiled; and the lean, tanned face, the keen eyes, momentarily became those of a boy.

“I think you’re the bird I’m looking for. You served with distinction in the United States Army, and come to me highly recommended. May I suggest that you have some personal animus against the Communist regime in China?”

“You may. I have. They brought about my father’s death and ruined our business.”

Nayland Smith re-lighted his briar pipe. “An excellent incentive. But it’s my duty to warn you of the kind of job you’re taking on. Right from the moment you leave this office you’re on your own. You’re an undercover agent—a man alone. Neither London nor Washington knows you. But we shall be in constant touch. You’ll be helping to save the world from slavery. And I know your heart’s in the game.”

Tony nodded; stubbed out his cigarette in an ash-tray.

“No man could be better equipped for what you have to do. You were born here, and you speak the language fluently. With your cast of features you can pass for Chinese. There’s no Iron Curtain here. But there are two Bamboo Curtains. The first has plenty of holes in it; the second so far has proved impenetrable.

Oddly enough, it isn’t in the Peiping area, but up near the Tibetan frontier. Have to know the identity of the big man it conceals. He’s the real power behind the Communist regime.”

“But he must come out sometimes,” Tony protested.

“He does. He moves about like a shadow. All we can learn about him is that he’s known and feared as ‘The Master’. His base seems to be somewhere in the province of Szechuan—and this province is behind the Second Bamboo Curtain!”

“Is that where you want me to go, Sir Denis?”

“It is. You could get there through Burma—”

“I could get a long way from right here, with a British passport, as a representative of, say, Vickers. Then I could disappear and become a Chinese coolie from Hong Kong—that’s safe for me—looking for a lost relative or girl friend, or somebody.”

Make your choice, McKay. I’d love to go, myself, but I can’t leave my base at the moment. I have a shrewd idea about the identity of The Master. That’s why I’m here.”

“You think you know who he is?”

“I think he is the president of the most dangerous secret society in the world, the Si-Fan—Dr. Fu Manchu.”

“Dr. Fu Manchu!”

“I believe he’s up to his old game, running with the hare and

hunting with the hounds—”

There was a sound resembling the note of a tiny bell. Nayland Smith checked his words and adjusted what looked like an Air Force wrist watch. Raising his hand, he began to speak into it. Tony realized that it must be some kind of walkie-talkie. The conversation was unintelligible, but when it ended, Nayland Smith glanced at him in an odd way.

“One of my contacts in Szechuan,” he explained drily. “Reports the appearance of another Cold Man in Chia-Ting. They’re creating a panic.”

“A Cold Man? I don’t understand.”

“Nor do I. But it’ll be one of your jobs to find out. They are almost certainly monstrosities created by Dr. Fu Manchu. I know his methods. They seem to be Burmese or Tibetans. Orders are issued that anyone meeting a Cold Man must instantly report to the police; that on no account must the creature be touched.”

“Why?”

“I can’t say. But they have been touched—and although they’re walking about, their bodies are said to be icily cold.”

“Good God! Zombies—living dead men!”

“And they always appear in or near Chia-Ting. You should head for there.”

“It sounds attractive!” Tony grinned.

“You’ll have one of these.” Nayland Smith tapped the instrument he wore on his wrist. “I may as well confess it’s a device we pinched from Dr. Fu Manchu. Captured on a prisoner. Looks like a wrist watch. One of our research men broke down the formula and now a number of our agents are provided with them. You can call me here at any time, and I can call you. Whatever happens, don’t lose it. Notify me regularly where you are—if anything goes wrong, get rid of it fast.”

“I’m all set to start.”

“There’s some number one top secret being hidden in Szechuan. Military Intelligence thinks it’s a Soviet project. I believe it’s a Fu Manchu project. He may be playing the Soviets at their own game. Dr. Fu Manchu has no more use for Communism than I have for Asiatic ‘flu. But so far all attempts to solve the puzzle have come apart. Local agents have only limited use, but you may find them helpful and they’ll be looking out for you. You’ll have the sign and countersigns. Dine with me tonight and I’ll give you a thorough briefing . . .”

Chapter II

There was a rat watching him. In the failing light he couldn’t see the thing; but he could see its eyes. Waiting hungrily, no doubt, for any scraps of rice he might leave in the bowl. Well, the rat would be in luck. The rice was moldy.

Tony McKay drank a little more tepid water and then lay back on his ticky mattress, his head against the wall, looking up at a small, square window. Iron bars criss-crossed the opening and now, as dusk fell, hardly any light came in. He could have dealt with the iron bars, in time, but the window was just out of reach—two inches out of reach.

It was another example of Chinese ingenuity, like the platter of ripe peaches his jailer had left in the dungeon one morning. By walking to the end of the chain clamped to his right ankle and lying flat, he could stretch his arm across the grimy floor—to within two inches of the fruit!

But none of their cunning tricks would pay off. Physically, he was getting below par, but his will remained strong as on the day he left Hong Kong, unless . . .

He dismissed the thought.

A dark shape crossed the pattern of the bars, became lost in shadows of a stone ledge which ran from the window around the angle to the grilled door. Two more wicked little eyes appeared beside the pair in the comer of his cell. The rat’s mate had joined up.

He didn’t mind them. In their repulsive way, they formed a sort of link with the free world outside. And he was sorry for any creature that was hungry, except the horrible small ones which inhabited his straw mattress and filled the night with misery.

He fell into a sort of dozing reverie.

These reveries had saved his sanity, given him the strength to carry on.

It was hard to grasp the fact that only two weeks ago he had been in Hong Kong. Throughout the first week he had kept in close touch with Nayland Smith, and this awful sense of loneliness which weighed him down now had not swept over him. Once he had overcome his stage fright on first assuming the part of Chi Foh, a Hong Kong fisherman, he had begun to enjoy his mission . . .

There were faint movements in the corridor, but they ceased, and Tony returned again to the recent past which now seemed so distant . . .

Anyway, he had penetrated the Second Bamboo Curtain—was still behind it. Of the mystery brain which Sir Denis Nayland Smith believed to be that of the fabulous Dr. Fu Manchu he had learned less than nothing. But in one part of his mission he had succeeded. The discovery had been made because of the thoroughness with which he identified himself with his assumed part of a Hong Kong fisherman seeking a missing fiancée. He had selected a remote riverside village not far above Chia-Ting on the Ya Ho River as the place to which his mythical girl friend had been taken by her family.

Quite openly he canvassed the inhabitants, so that if questioned later he could call witnesses to support his story. And it was from a kindly old woman whose sympathy with his quest made him feel an awful hypocrite that he got the clue which led him to his goal.

She suggested that the missing girl might be employed in “the Russian camp.” It appeared that a grand-daughter of hers had worked there for a time.

“Where is this camp?” he asked.

It was on the outskirts of the village.

“What are Russians doing here?” he wanted to know.

They were employed to guard the leprosy research centre. Even stray dogs who came too near to the enclosure were shot to avoid spreading infection. The research centre was a mile outside the village.

“When did your grand-daughter leave, and why?” he inquired.

To get married, the old woman told him. She left only a month ago. The wages were good and the work light. She and her husband now lived in the village.

Tony interviewed the girl, describing “Nan Cho”, his missing fiancée, but was assured that she was not employed at the Russian camp. He gathered that there were not more than forty men there in charge of a junior officer and two sergeants . . .

How vividly he remembered his reconnaissance in the grey dawn next morning!

The camp was a mere group of hutments, with a cookhouse and an orderly room displaying the hammer and sickle flag. He estimated that even by Russian standards it couldn’t accommodate more than forty men. From cover he studied it awhile, and when the sleeping camp came to life decided that it was the most slovenly outfit he had ever come across. The entire lack of discipline convinced him that the officer in charge must be a throw-out sent to this dismal post as useless elsewhere.

There was a new and badly-made road leading from the camp up into the hills which overlooked the river. He was still watching when a squad of seven men appeared high up the road, not in any kind of order but just trudging along as they pleased. The conclusion was obvious. The guard on the research center had been relieved.

He made a wide detour. There was plenty of cover on both sides of the road, oaks and scrub, and not a patch of cultivation that he could see. It was a toilsome journey, for he was afraid to take to the winding road even when far out of sight of the camp below. This was fortunate; for suddenly, beyond another bend of the serpentine road, he came in sight of the research station.

It was unlike anything he had anticipated.

A ten-foot wire fence surrounded an area, or so he guessed, of some twelve acres. Roughly in the center of the area, which had been mown clear of vegetation and looked like a huge sheet of brown paper, he saw a group of buildings roofed with corrugated iron. One of them had what he took to be a smokestack or ventilation shaft.

The road ended before a gate in the wire fence. There was a wooden hut beside the gate, and a Russian soldier stood there, his rifle resting against the hut. He was smoking a cigarette.

And presently another man appeared walking briskly along outside the wire. The smoker carefully stubbed out his cigarette, stuck it behind his ear, and shouldered his rifle. The other man stepped into the hut—evidently the corporal in charge, who had posted the remaining five men of his squad at points around the circumference of the fence.

The cunning of Soviet propaganda! Leprosy is a frightening word, although leprosy had rarely appeared in Szechuan. But the mere name was enough to keep all at a distance.

This was the germ factory . . .

Where had he gone wrong?

Chung Wa-Su? Was it possible that Chung had betrayed him? It would be in line with Chinese thinking (if he. Tony, had aroused suspicion) to plant a pretended helper in his path. Yet all that Chung Wa-Su had done was to admit that he worked for Free China and to give him directions how best to cross the Yangtsze into Szechuan without meeting with frontier guards.

It was hard to believe.

There was the man he knew simply as Li. Who was Li? True, Tony hadn’t trusted him very far although he had given sign and countersign, but all the same it was Li who had put him in touch with Chung Wa-Su.

Had Li been seized, forced to speak? Or was it possible that a report of his, Tony’s visit to Hua-Tzu had preceded him down the river? Questioned, he had spoken freely about the visit; for although he knew, now, what was hidden there, he couldn’t go back on his original plan without destroying the carefully built-up evidence of the purpose of his long journey.

He fell into an uneasy doze. He could hear, and smell, the rats in his rice bowl. As he slipped into sleep, his mind carried him back to his last examination by the dreadful creature called Colonel Soong . . .

“If you searched this village you speak of, looking for some girl, you can tell me the name of the former mandarin who lives in the big house.”

“There is no large house in Hua-Tzu.”

“I mean the house is in the hills.”

“I saw no house in the hills.”

His heart warmed again in his near-dream state. There were few Americans, or Europeans either, who could have sustained the character of a love-lorn fisherman from Hong Kong under the fire of those oblique, ferocious eyes.

Yes, Sir Denis Nayland Smith was a good picker. No man could be better fitted for the job than one born in China, whose maternal grandmother had belonged to an old Manchurian family . . .

In a small room, otherwise plainly furnished, a man sat in a massive, high-backed ebony chair behind a lacquer desk. The desk glistened in the light of a silk-shaded lantern which hung from the ceiling, so that golden dragons designed on the lacquer panels seemed to stir mysteriously.

The man seated there wore a loose yellow robe. His elbows rested on the desk, and his fingers—long, yellow fingers—were pressed together, so that he might have suggested to an observer the image of a praying mantis. He had the high brow of a philosopher and features indicating great intellectual power. This aura of mental force seemed to be projected by his eyes, which were of a singular green color, and as he stared before him, as if at some distant vision, from time to time they filmed over in an extraordinary manner.

The room, in which there lingered a faint, sickly smell of opium, was completely silent.

And this silence was scarcely disturbed when a screen door opened and an old Chinese came in on slippered feet. His face, in which small, twinkling eyes looked out from an incredible map of wrinkles, was that of a man battered in a long life of action, but still unbowed, undaunted. He wore an embroidered robe and a black cap topped by a coral bead.

He dropped down on to cushions heaped on the rugs, tucking his hands into the loose sleeves of his robe, and remained there, still as a painted Buddha, watching the other man.

The silence was suddenly and harshly broken by the voice of the dreamer at the lacquer desk. It was a strange voice, stressing the many sibilants in the Chinese language

and emphasizing the gutturals.

“And so, Tsung-Chao, I am back again in China—a fugitive from the West, but a power in the East. You, my old friend, are restored to favor General Huan Tsung-Chao, a former officer of the Chinese Empire, now Communist governor of a province! A triumph for the Si-Fan. But similar phenomena have appeared in Soviet Russia. You have converted Szechuan into a fortress in which I am secure. You have done well.”

“Praise from the Master warms my old heart.”

“It is a stout heart—and not so old as mine.”

“All that I have done has been under your direction.”

“What of the reorganization of the People’s Army? You are too modest, Tsung-Chao. But between us we have gained the confidence of Peiping. I have unlimited authority, for Peiping remains curiously, but fortunately, ignorant of the power of the Si-Fan.”

“I pray that their ignorance may continue.”

“I have inspected many provinces, and have found our work progressing well. I detected several United States agents, and many of Free China. But Free China fights for the same goal as the Si-Fan.”

“But not for the same leader, Master!”

Dr. Fu Manchu smiled. His smile was more terrifying than his frown.

“You mean for the same Emperor! We must be patient.” His voice rose on a note of exaltation. “I shall restore this ancient Empire to more than its former glory! Communism, with its vulgarity, its glorification—and enslavement—of the workers, I shall sweep from the earth! What Bonaparte did I shall do, and as he did, I shall win control of the West as well as of the East!”

“I await the day, Master!”

“It will come. But if the United States, Britain, or particularly Soviet Russia, should unmask the world-wide conspiracy of the Si-Fan, all our plans would be laid in ashes! So, when I am in China, my China, I must travel incognito; I am a shadow.”

The old general smiled; a wrinkled but humorous smile. “I can answer for most of our friends in Formosa. From the United States agents you have little to fear. None of them knows you by sight—only by repute. I have entertained several Soviet visitors—and your name stands high with the Kremlin. But news reached me yesterday that Nayland Smith has left England, and I believe is in Hong Kong.”