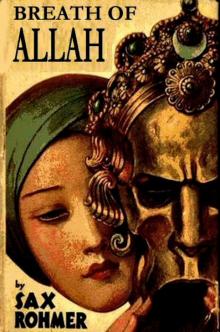

Breath of Allah

Sax Rohmer

Breath of Allah

Sax Rohmer

An excerpt from the first chapter:

...The illusion persisting, I determined that it was due to the unnatural strain imposed upon my vision, and although I recognized that time was precious I found myself compelled temporarily to desist, since nothing was to be gained by watching these letters which danced from side to side of the parchment, sometimes in groups and sometimes singly, so that I found myself pursuing one slim Arab A ('Alif) entirely up the page from the bottom to the top where it finally disappeared under the thumb of the Lady Zuleyka!

Breath of Allah

Sax Rohmer

I

For close upon a week I had been haunting the purlieus of the Muski, attired as a respectable dragoman, my face and hands reduced to a deeper shade of brown by means of a water-color paint (I had to use something that could be washed off and grease-paint is useless for purposes of actual disguise) and a neat black moustache fixed to my lip with spirit-gum. In his story Beyond the Pale, Rudyard Kipling has trounced the man who inquires too deeply into native life; but if everybody thought with Kipling we should never have had a Lane or a Burton and I should have continued in unbroken scepticism regarding the reality of magic. Whereas, because of the matters which I am about to set forth, for ten minutes of my life I found myself a trembling slave of the unknown.

Let me explain at once that my undignified masquerade was not prompted by mere curiosity or the quest of the pomegranate, it was undertaken as the natural sequel to a letter received from Messrs. Moses, Murphy and Co., the firm which I represented in Egypt, containing curious matters affording much food for reflection. "We would ask you," ran the communication, "to renew your inquiries into the particular composition of the perfume 'Breath of Allah,' of which you obtained us a sample at a cost which we regarded as excessive. It appears to consist in the blending of certain obscure essential oils and gum-resins; and the nature of some of these has defied analysis to date. Over a hundred experiments have been made to discover substitutes for the missing essences, but without success; and as we are now in a position to arrange for the manufacture of Oriental perfume on an extensive scale we should be prepared to make it well worth your while (the last four words characteristically underlined in red ink) if you could obtain for us a correct copy of the original prescription."

The letter went on to say that it was proposed to establish a separate company for the exploitation of the new perfume, with a registered address in Cairo and a "manufactory" in some suitably inaccessible spot in the Near East.

I pondered deeply over these matters. The scheme was a good one and could not fail to reap considerable profits; for, given extensive advertising, there is always a large and monied public for a new smell. The particular blend of liquid fragrance to which the letter referred was assured of a good sale at a high price, not alone in Egypt, but throughout the capitals of the world, provided it could be put upon the market; but the proposition of manufacture was beset with extraordinary difficulties. The tiny vial which I had despatched to Birmingham nearly twelve months before had cost me close upon £100 to procure, for the reason that "Breath of Allah" was the secret property of an old and aristocratic Egyptian family whose great wealth and exclusiveness rendered them unapproachable. By dint of diligent inquiry I had discovered the attar to whom was entrusted certain final processes in the preparation of the perfume—only to learn that he was ignorant of its exact composition. But although he had assured me (and I did not doubt his word) that not one grain had hitherto passed out of the possession of the family, I had succeeded in procuring a small quantity of the precious fluid.

Messrs. Moses, Murphy and Co. had made all the necessary arrangements for placing it upon the market, only to learn, as this eventful letter advised me, that the most skilled chemists whose services were obtainable had failed to analyse it.

One morning, then, in my assumed character, I was proceeding along the Sharia el-Hamzawi seeking for some scheme whereby I might win the confidence of Mohammed er-Rahman the attar, or perfumer. I had quitted the house in the Darb el-Ahmar which was my base of operations but a few minutes earlier, and as I approached the corner of the street a voice called from a window directly above my head: "Said! Said!"

Without supposing that the call referred to myself, I glanced up, and met the gaze of an old Egyptian of respectable appearance who was regarding me from above. Shading his eyes with a gnarled hand—

"Surely," he cried, "it is none other than Said the nephew of Yussuf Khahig! Es-selam 'aleykum, Said!"

"Aleykum, es-selam," I replied, and stood there looking up at him. "Would you perform a little service for me, Said?" he continued. "It will occupy you but an hour arid you may earn five piastres."

"Willingly," I replied, not knowing to what the mistake of this evidently half-blind old man might lead me. I entered the door and mounted the stairs to the a room in which he was, to find that he lay upon a scantily covered diwan by the open window.

"Praise be to Allah (whose name be exalted)!" he exclaimed, "that I am thins fortunately enabled a to fulfil my obligations. I sometimes suffer from an old serpent bite, my son, and this morning it has obliged me to abstain from all movement. I am called Abdul the Porter, of whom you will have heard your uncle speak; and although I have long retired from active labor myself, I contract for the supply of porters and carriers of all descriptions and for all purposes; conveying fair ladies to the hammam, youth to the bridal, and death to the grave. Now, it was written that you should arrive at this timely hour."

I considered it highly probable that it was also written how I should shortly depart if this garrulous old man continued to inflict upon me details of his absurd career. However—

"I have a contract with the merchant, Mohammed er-Rahman of the Suk el-Attarin," he continued, "which it has always been my custom personally to carry out."

The words almost caused me to catch my breath; and my opinion of Abdul the Porter changed extraordinary. Truly my lucky star had guided my footsteps that morning!

"Do not misunderstand me," he added. "I refer not to the transport of his wares to Suez, to Zagazig, to Mecca, to Aleppo, to Baghdad, Damascus, Kandahar, and Pekin; although the whole of these vast enterprises is entrusted to none other than the only son of my father: I speak, now, of the bearing of a small though heavy box from the great magazine and manufactory of Mohammed er-Rahman at Shubra, to his shop in the Suk el-Attarin, a matter which I have arranged for him on the eve of the Molid en-Nebi (birthday of the Prophet) for the past five-and-thirty years. Every one of my porters to whom I might entrust this special charge is otherwise employed; hence my observation that it was written how none other than yourself should pass beneath this window at a certain fortunate hour."

Fortunate indeed had that hour been for me, and my pulse beat far from normally as I put the question: "Why, O Father Abdul, do you attach so much importance to this seemingly trivial matter?"

The face of Abdul the Porter, which resembled that of an intelligent mule, assumed an expression of low cunning.

"The question is well conceived," he said, raising a long forefinger and wagging it at me. "And who in all Cairo knows so much of the secrets of the great as Abdul the Know-all, Abdul the Taciturn! Ask me of the fabled wealth of Karafa Bey and I will name you every one of his possessions and entertain you with a calculation of his income, which I have worked out in nuss-faddah!

1 Ask me of the amber mole upon the shoulder of the Princess Aziza and I will describe it to you in such a manner as to ravish your soul! Whisper, my son"—he bent towards me confidentially—"once a year the merchant Mohammed er-Rahman prepares for the Lady Zuleyka a quantity of the perfume which impious tradition has called 'Breath of Allah.' T

he father of Mohammed er-Rahman prepared it for the mother of the Lady Zuleyka and his father before him for the lady of that day who held the secret—the secret which has belonged to the women of this family since the reign of the Khalif el-Hakim from whose favorite wife they are descended. To her, the wife of the Khalif, the first dirhem (drachm) ever distilled of the perfume was presented in a gold vase, together with the manner of its preparation, by the great wizard and physician Ibn Sina of Bokhara" (Avicenna).

"You are well called Abdul the Know-all!" I cried in admiration. "Then the secret is held by Mohammed er-Rahman?"

"Not so, my son," replied Abdul. "Certain of the essences employed are brought, in sealed vessels, from the house of the Lady Zuleyka, as is also the brass coffer containing the writing of Ibn Sina; and throughout the measuring of the quantities, the secret writing never leaves her hand."

"What, the Lady Zuleyka attends in person?"

Abdul the Porter inclined his head serenely.

"On the eve of the birthday of the Prophet, the Lady Zuleyka visits the shop of Mohammed er-Rahman, accompanied by an imam from one of the great mosques."

"Why by an imam, Father Abdul?"

"There is a magical ritual which must be observed in the distillation of the perfume, and each essence is blessed in the name of one of the four archangels; and the whole operation must commence at the hour of midnight on the eve of the Molid en-Nebi."

He peered at me triumphantly.

"Surely," I protested, "an experienced attar such as Mohammed er-Rahman would readily recognize these secret ingredients by their smell?"

"A great pan of burning charcoal," whispered Abdul dramatically, "is placed upon the floor of the room, and throughout the operation the attendant imam casts pungent spices upon it, whereby the nature of the secret essences is rendered unrecognizable. It is time you depart, my son, to the shop of Mohammed, and I will give you a writing making you known to him. Your task will be to carry the materials necessary for the secret operation (which takes place to-night) from the magazine of Mohammed er-Rahman at Shubra, to his shop in the Suk el-Attarin. My eyesight is far from good, Said. Do you write as I direct and I will place my name to the letter."

II

The words "well worth your while" had kept time to my steps, or I doubt if I should have survived the odious journey from Shubra. Never can I forget the shape, color, and especially the weight, of the locked chest which was my burden. Old Mohammed er-Rahman had accepted my service on the strength of the letter signed by Abdul, and of course, had failed to recognize in

1 A nuss-faddah equals a quarter of a farthing.

"Said" that Hon. Neville Kernaby who had certain confidential dealings with him a year before.

But exactly how I was to profit by the fortunate accident which had led Abdul to mistake me for someone called "Said" became more and more obscure as the box grew more and more heavy.

So that by the time that I actually arrived with my burden at the entrance to the Street of the Perfumers, my heart had hardened towards Abdul the Know-all; and, setting my box upon the ground, I seated myself upon it to rest and to imprecate at leisure that silent cause of my present exhaustion.

After a the my troubled spirit grew calmer, as I sat there inhaling the insidious breath of Tonquin musk, the fragrance of attar of roses, the sweetness of Indian spikenard and the stinging pungency of myrrh, opoponax ,and ihlang-ylang. Faintly I could detect the perfume which I have always counted the most exquisite of all save one—that delightful preparation of Jasmine peculiarly Egyptian. But the mystic breath of frankincense and erotic fumes of ambergris alike left me unmoved; for amid these odors, through which it has always seemed to me that that of cedar runs thematically, I sought in vain for any hint of "Breath of Allah."

Fashionable Europe and America were well represented as usual in the Suk el-Attarin, but the little shop of Mohammed er-Rahman was quite deserted, although he dealt in the most rare essences of all. Mohammed, however, did not seek Western patronage, nor was there in the heart of the little white-bearded merchant any envy of his seemingly more prosperous neighbors in whose shops New York, London, and Paris smoked amber-scented cigarettes, and whose wares were carried to the uttermost corners of the earth. There is nothing more illusory than the outward seeming of the Eastern merchant. The wealthiest man with whom I was acquainted in the Muski had the aspect of a mendicant; and whilst Mohammed's neighbors sold phials of essence and tiny boxes of pastilles to the patrons of Messrs. Cook, were not the silent caravans following the ancient desert routes laden with great crates of sweet merchandise from the manufactory at Shubra? To the city of Mecca alone Mohammed sent annually perfumes to the value of two thousand pounds sterling; he manufactured three kinds of incense exclusively for the royal house of Persia; and his wares were known from Alexandria to Kashmir, and prized alike in Stambul and Tartary. Well might he watch with tolerant smile the more showy activities of his less fortunate competitors.

The shop of Mohammed er-Rahman was at the end of the street remote from the Hamzawi (Cloth Bazaar), and as I stood up to resume my labors my mood of gloomy abstraction was changed as much by a certain atmosphere of expectancy—I cannot otherwise describe it—as by the familiar smells of the place. I had taken no more than three paces onward into the Suk ere it seemed to me that all business had suddenly become suspended; only the Western element of the throng remained outside whatever influence had claimed the Orientals. Then presently the visitors, also becoming aware of this expectant hush as I had become aware of it, turned almost with one accord, and following the direction of the merchants' glances, gazed up the narrow street towards the Mosque of el-Ashraf.

And here I must chronicle a curious circumstance. Of the Imam Abu Tabah I had seen nothing for several weeks, but at this moment I suddenly found myself thinking of that remarkable man.

Whilst any mention of his name, or nickname—for I could not believe "Tabah" to be patronymic—amongst the natives led only to pious ejaculations indicative of respectful fear, by the official world he was tacitly disowned. Yet I had indisputable evidence to show that few doors in Cairo, or indeed in all Egypt, were closed to him; he came and went like a phantom. I should never have been surprised, on entering my private apartments at Shepheard's, to have found him seated therein, nor did I question the veracity of a native acquaintance who assured me that he had met the mysterious imam in Aleppo on the same morning that a letter from his partner in Cairo had arrived mentioning a visit by Abu Tabah to el-Azhar. But throughout the native city he was known as the Magician and was very generally regarded as a master of the ginn. Once more depositing my burden upon the ground, then, I gazed with the rest in the direction of the mosque.

It was curious, that moment of perfumed silence, and my imagination, doubtless inspired by the memory of Abu Tabah, was carried back to the days of the great khalifs, which never seem far removed from one in those mediaeval streets. I was transported to the Cairo of Harun al Raschid, and I thought that the Grand Wazir on some mission from Baghdad was visiting the Suk el-Attarin Then, stately through the silent group, came a black-robed, white-turbaned figure outwardly similar to many others in the bazaar, but followed by two tall muffled negroes. So still was the place that I could hear the tap of his ebony stick as he strode along the centre of the street.

At the shop of Mohammed er-Rahman he paused, exchanging a few words with the merchant, then resumed his way, coming down the Suk towards me. His glance met mine, as I stood there beside the box; and, to my amazement, he saluted me with smiling dignity and passed on. Had he, too, mistaken me for Said—or had his all-seeing gaze detected beneath my disguise the features of Neville Kernaby?

As he turned out of the narrow street into the Hamzawi, the commercial uproar was resumed instantly, so that save for this horrible doubt which had set my heart heating with uncomfortable rapidity, by all the evidences now about me his coming might have been a dream.

III

Filled with misgivings, I

carried the box along to the shop; but Mohammed er-Rahman's greeting held no hint of suspicion.

"By fleetness of foot thou shalt never win Paradise," he said.

"Nor by unseemly haste shall I thrust others from the path," I retorted.

"It is idle to bandy words with any acquaintance of Abdul the Porter's," sighed Mohammed; "well do I know it. Take up the box and follow me."

With a key which he carried attached to a chain about his waist, he unlocked the ancient door which alone divided his shop from the outjutting wall marking a bend in the street. A native shop is usually nothing more than a double cell; but descending three stone steps, I found myself in one of those cellar-like apartments which are not uncommon in this part of Cairo. Windows there were none, if I except a small square opening, high up in one of the walls, which evidently communicated with the narrow courtyard separating Mohammed's establishment from that of his neighbor, but which admitted scanty light and less ventilation. Through this opening I could see what looked like the uplifted shafts of a cart. From one of the rough beams of the rather lofty ceiling a brass lamp hung by chains, and a quantity of primitive chemical paraphernalia littered the place; old-fashioned alembics, mysterious looking jars, and a sort of portable furnace, together with several tripods and a number of large, flat brass pans gave the place the appearance of some old alchemist's den. A rather handsome ebony table, intricately carved and inlaid with mother-o'-pearl and ivory, stood before a cushioned diwan which occupied that side of the room in which was the square window.

"Set the box upon the floor," directed Mohammed, "but not with such undue dispatch as to cause thyself to sustain an injury."

That he had been eagerly awaiting the arrival of the box and was now burningly anxious to witness my departure, grew more and more apparent with every word. Therefore—