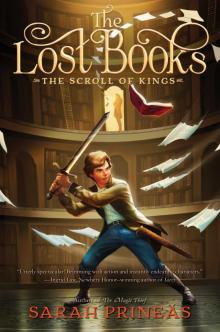

The Lost Books

Sarah Prineas

Dedication

To my dear friend Michelle Edwards.

“Strength to your sword arm!”

Epigraph

. . . books are people

—people who have managed to stay alive

by hiding between the covers of a book.

—E. B. WHITE

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Books by Sarah Prineas

Back Ads

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

The pages were bothering Alex.

The pages, of course, were the magical pieces of paper that acted as the librarian’s servants. They floated around doing whatever Master Farnsworth ordered, as long as it was something simple, like “Fetch me a cup of tea,” and not something complicated, like “Go alphabetize the encyclopedias.”

Alex, as the librarian’s assistant, or apprentice, or whatever he was, did not have pages of his own.

So when his master’s pages fluttered around his head like giant anxious moths, he tried to ignore them. He had work to do. Librarian Farnsworth had ordered him to compare two alphabetized book lists. Alex had his elbows on the table and his hands gripping his hair, forcing himself to concentrate. He was on the letter R. Just eight letters to go, and he’d be done.

Gritting his teeth, he started on the letter S.

A page flitted past him.

“Go away,” Alex said to it, and kept his eyes grimly on his work.

Another page floated past. Then another one.

Master Farnsworth’s pages were made of paper that was wrinkled and yellowed and tattered around the edges, and one of them had been torn nearly in half and then pasted back together again so that it was sort of scarred down the middle.

The scarred page rustled, trying to get Alex’s attention.

“All right, all right,” he muttered. “Just a moment.” Carefully he marked his place and was about to look up when the page rolled itself into a tube and bonked him on the head.

“What was that for?” Alex protested. It hadn’t hurt, but it was annoying.

The scarred page unrolled itself. Alex saw a single word written on it in faint, almost illegible letters.

[defunct]

“What?” he asked.

Another page darted closer. A jumble of letters stuttered across its surface and then disappeared. Then four more pages clustered around Alex, shivering. That was six total—all of Master Farnsworth’s pages, as far as he knew. This was not normal behavior.

“Defunct?” Alex asked, getting to his feet. They were trying to tell him something, but the pages were simple creatures. They didn’t always make sense.

The scarred page—the boldest one—floated closer. Shaky letters took shape on the yellowed paper.

[expired

overdue

off the shelf]

All of the pages were trembling, and crowding even closer. Alex felt a sudden jolt of worry. “It’s all right,” he tried to reassure them. “Do you want me to come with you?”

At that, the pages whirled around him, then streamed toward the door at the end of the reading room.

Feeling suddenly certain that something awful had happened, Alex followed them, hurrying between looming bookshelves until he reached the quiet corner where the librarian sometimes napped. His cot was surrounded by stacks of books. Like any proper librarian, Master Farnsworth did not fold over a corner of a page to mark his place, so his books were bristling with torn-off bits of paper used to mark where he’d stopped reading.

With the pages hovering at his shoulder, Alex stood beside the cot, looking down at his master. The old man lay with his gnarled hands holding a book that was open, facedown, on his chest.

He must have fallen asleep while reading. The librarian, being ancient, slept a good deal, and didn’t move around much at the best of times. It was a shame to wake him. He looked so peaceful, lying there.

Too peaceful. Alex leaned closer. Oh, no. The librarian wasn’t breathing.

“Master Farnsworth?” Alex went to his knees beside the cot. “Sir?” He reached out to shake the librarian’s shoulder to wake him up. But his master was stiff as a board and pretty solidly dead.

He’d probably been gone for hours.

Alex swallowed several times, blinked several more times, then scrambled to his feet and stood looking sorrowfully down at the body.

The librarian had been a creature of dust and paper; a strong wind could have blown him away. He’d been skinny and bent, his face a mass of wrinkles, his hair spun-white cobwebs. To read, he peered through a pair of spectacles that had inch-thick lenses smudged with fingerprints.

Alex frowned. There was something strange.

The book rested on the librarian’s chest, as if the old man had been reading it when he died. But he wasn’t wearing his spectacles.

Crouching, Alex gently pulled the book from under his master’s folded hands. The first thing he noticed about it was a symbol burned into the leather cover.

Below it, the title.

VINES:

PLANTS OF WONDER

That was odd. As far as Alex knew, his master had no interest at all in gardening.

The second thing Alex noticed was that his master’s pages had fled from the room. Or maybe, now that they’d delivered their message, they had disappeared forever. He didn’t know what happened to a librarian’s pages after their master had died.

He wondered why Master Farnsworth had been reading about vines. Without thinking, he flipped open the book.

He turned to the first chapter. His eyes were drawn to the words at the top of the page, and he started to read.

The vine is a quite wondrous plant. It seems simple, yet it can grow at astounding speed. It can cling, twine around, climb, and in the case of some species, it can strangle.

Alex kept reading. He turned a page.

And realized that the tips of his fingers had gone numb.

And that he couldn’t look away.

The numbness was spreading to his hands, which were clenched around the edges of the book. His heart pounded.

And then, the merest sliver of a pale green tendril emerged from behind the next page, which he hadn’t turned yet. It quested about, almost like it was sniffing.

It was just a tiny vine, no bigger than a pea shoot.

Alex watched his own hand reach out and turn the page.

Exposed, the little vine uncoiled itself and nosed toward him. A second later, it had curled around his wrist.

“Gah!” Alex shouted. He shook the vine off his hand and dropped the book. It lay open on the dusty floor. As he watched, the tiny vine sniffed about. Then it fixed on him again. It twined from the book, growing longer and thicker, a green rope studded with shiny leaves. Like a snake, it crawled over the floor toward him.

Alex backed away, looking for anythin

g he could use to fend it off. A second vine erupted from the book and slithered across the floor. Before he could dodge it, the first vine had wrapped itself around his ankle.

And then it was twining around his leg, and it had grown thorns, which bit into him.

With sudden horror, Alex realized what had happened to Master Farnsworth. The librarian had opened the book, started to read, and then . . .

His hands shaking, Alex ripped the vine off his leg. Its thorns tore at his skin, and he left blood spattered around him as he stumbled back.

He had to get the book closed—or he’d end up just like his master.

The vine sniffed at the drops and then sent out little rootlets, which poked into the blood and sucked it up. Then, its strength renewed, it surged after him again.

Alex grabbed up a book from his master’s reading pile and flung it at the vine. It dodged it and struck at him like a snake. The other vine was growing up the wall and sending out more tendrils that reached for him like long, green fingers.

He ducked and hurled another book as a thick, ropy, almost muscular vine reached for him. Looking wildly around, he saw the vines book lying open on the floor. At the same moment, all of the vines hissed through the air, coming after him. Fighting through the clinging tendrils, Alex lunged toward the book. He reached for it, but the vines pulled him back, dragging him over the stone floor.

He clenched his teeth. “I don’t think so,” he told the vines.

A tendril looped around his neck and tightened like strangling fingers. Black spots appeared in his vision, and he gasped for breath.

With an almighty effort, Alex lunged toward the book, grabbed it, and slammed it closed.

The vines evaporated like smoke.

Panting for breath, Alex got to his feet and stared down at the book. He rubbed his neck.

Well. That had been interesting.

He knew what a librarian was supposed to be. Master Farnsworth had been a cataloger of books—books that sat tamely on their shelves gathering dust—and a keeper of the keys that kept books safely locked up. If anyone had a question that could only be settled by looking at a book, they would go to a librarian, who would consult his or her collection and come back with an answer.

But Alex had reasons—very good reasons—for suspecting that librarians had once been much more than just catalogers and keepers.

And that books were much more than they seemed.

He wished he could ask his master about it.

But he couldn’t. Because the librarian was dead.

The library was owned by Dowager Duchess Purslane, who was obsessed with two things.

The first thing was genealogy. The library in her castle was stuffed with tediously boring family archives, insipid family letters, and crumbling diaries written by ancestors who had been dead for three hundred years. That kind of thing.

As far as Alex was concerned, barely any of it counted as real books, and almost all of it could be burned to the ground without any loss.

The second thing was roses.

Alex found the duchess in the castle’s extensive gardens, bent over a bush with pruning shears in one hand and a bunch of late-autumn blooms in the other.

“Duchess Purslane,” Alex began, “I have some bad news.”

The duchess was tall and rather bony, and had the rich brown skin of the old nobility. She peered shortsightedly at him over her shoulder. “Who are you?”

He gritted his teeth. “The librarian’s apprentice.”

She turned back to the roses. “The librarian doesn’t have an apprentice.” Snip, snip, snip went the garden shears.

“Yes he does,” Alex corrected her, keeping a grip on his patience. “He did, I mean. I’ve been here for months.”

More snipping. “Well, what do you want, boy?” She cast him a frowning glance, from the top of his dusty blond head, to his inky fingers and shabby clothes, to the tips of his worn shoes. “Bad news, I think you said?”

“Yes.” Alex nodded. “The librarian is dead.”

The dowager duchess straightened and blinked rapidly. A hand went to her chest. “Oh dear. Dead, you say?”

“Yes,” Alex answered. “He was very old, as you know.” Before she could comment, he went on. “He trained me well.” That was a complete lie, but she’d never know it. “I’ll take over as head librarian. I can begin immediately and set things to rights.”

“Wait a moment,” the duchess said slowly. “Now I remember you.”

Oh, blast it, Alex thought. Into a million tiny pieces.

The duchess pointed at him with the pruning shears. “You’re the one who wanted to destroy my library.”

“Not destroy,” Alex insisted.

“Destroy,” repeated the duchess. “You wanted to throw away the castle records!”

“Not all of them,” Alex said. “Just the useless things. After all, who needs copies of two-hundred-year-old laundry lists? Or,” he added, because he couldn’t help it, “a crumbling diary written by a soldier stationed at an outpost where nothing happens for twenty years?”

“That soldier was my great-grandmother’s second cousin once removed!” exclaimed the dowager duchess.

“Twenty years of It was foggy today,” Alex scoffed. “The sergeant-at-arms got drunk again. Chicken stew for dinner. Why even bother with it?”

The dowager duchess gasped. “Why . . . even . . .”

Relentlessly, Alex went on. “Papers like that don’t belong in a library. You might as well use them for wrapping up fish guts in the kitchen. Or for lining a birdcage. Or in the privy.”

“You dare suggest such a use for my family papers! You horrible, horrible boy!” She waved her roses in the direction of the castle, scattering petals around them both. “Out!”

“What?” Alex asked blankly. “You can’t throw me out. You’ve got a problem in your library. A big one.”

“You!” cried the dowager duchess. “The problem is you.”

“No, wait,” Alex protested. “Something snaky is going on in there. You need a librarian to deal with it.”

“Then I will get one.” The duchess brandished the pruning shears, and Alex stepped quickly back to avoid getting poked. “But not you. Get out. Pack your things and get out of my castle. You are no librarian, and you will never set foot in my library again!”

2

“No librarian,” Alex grumbled to himself. “What does she know about it?”

He was in a hurry. When he’d started back toward the castle library, the dowager duchess had gone in the other direction, and he knew where she was headed—to get her castle steward to toss him out the front gate.

But there was something he needed to do before he let that happen. It wasn’t pack his things, either. He didn’t have any things.

What he did have was plans.

Almost four months ago, when he’d convinced the librarian to take him on as an apprentice, he’d had good reasons for coming to Purslane Castle.

For one thing, anybody who might possibly be searching for him would never think of looking for him here. He was as good as dead and buried in the dowager duchess’s moldering, rose-encrusted castle.

For another thing, he’d suspected that Farnsworth, being ancient, knew secret librarian things and could answer some questions. Questions that had been eating away at Alex the way a biscuit beetle nibbled through the pages of an infested book.

One day he and the librarian had been drinking their weekly cup of tea together, after which the old man would show Alex things, like how to restitch a binding, or stop the damp from making a book turn moldy. These were important things for a librarian to know, but Alex was curious about something else.

“Sir,” he’d asked, when the librarian had finished showing off forty-two different kinds of frass.

Frass was bug droppings. By looking at what frass was left behind, you could tell what kinds of bugs were infesting the books in a library. Definitely not what he really needed to know.

>

“Master Farnsworth,” Alex had asked, “is there something strange about books?”

The librarian had been examining a little bottle of frass from a biscuit beetle. Deliberately, he’d slotted the bottle back into the box that contained forty-one other tiny jars of frass, all labeled in the librarian’s spidery script. Then Merwyn Farnsworth stroked his beard. When he spoke, he had a high voice, birdlike. “Books, strange? No. Certainly not. What an odd question to ask, ah . . . uh . . . boy.”

As usual, he’d forgotten Alex’s name.

“Not just strange,” Alex had persisted. “This is serious. Books are . . . they’re not just books, are they?”

The old man had shaken his head. “Books are not books? Whatever are you talking about?”

But he’d had a gleam in his eye when he’d said it. So Alex pushed. “You know,” he’d insisted. “Librarians keep books locked up and hidden away. There must be a reason for that. You know their secrets.”

“The only thing books do,” the old man had said, shaking his head, “is gather dust. Speaking of which, you’d better dust the duchess’s collection of her great-uncle’s letters.”

But Alex felt certain that his master knew a lot more than he was telling. Because at the very center of the castle library, he’d found a door to a room.

The door was made of thick ironwood. Banded with metal. Doorknob in the middle, and under it, a keyhole. It was pretty much impenetrable.

Something was in there, Alex knew it. Some kind of dangerous book.

Merwyn Farnsworth had the only key, and he’d kept it on a chain around his neck. Alex had asked him a thousand times to let him into the locked room.

Just to do some dusting, Alex would say. I won’t even look into the books. A total lie, that. The very second he got in there he would have pounced on them.

But it didn’t matter, because Master Farnsworth had just shaken his old, white head and put a knobbled hand over his chest, where the iron key to the room hung on its chain.

Well, Alex would get into it now.

He hurried into the castle library, and made his way to the remote corner where the librarian’s body lay.

He stood, surveying the small, dusty space, looking for the book called Vines: Plants of Wonder. Nobody, he was absolutely certain, had come into the room while he’d been telling the duchess about the librarian’s death, but the vines book was gone. Blast it, he’d missed his chance to examine it more carefully. There had been that odd symbol burned into its cover.