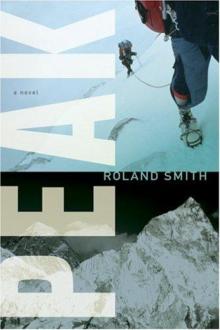

Peak

Roland Smith

Roland Smith

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

...

Copyright

Dedication

Map

MOLES KINE #1

THE ASSIGNMENT

THE HOOK

A COUPLE OF STITCHES & THE SLAMMER

CIRCLING THE DRAIN

THE TWINS

ROCK RATS

BANGKOK

THE SUMMIT HOTEL

GEAR OF THE DEAD

TIBET

PEAK EXPERIENCE

ROCK WEASELS

GASP

LATECOMERS

GAMOW BAG

ABC

LETTERS FROM HOME

MOLES KINE #2

SECRETS

BEAR AND BULL

CAMP FOUR

ARREST

FAMILY HISTORY

UNREST

BLINK

SHORTCUT

CAMP 3½

CAMPS FIVE AND SIX

TOP OF THE WORLD

DOWN THE MOUNTAINSIDE

DENOUEMENT

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

HARCOURT, INC.

Orlando Austin

New York San Diego

London

Copyright © 2007 by Roland Smith

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be

submitted online at www.harcourt.com/contact or mailed to the following address:

Permissions Department, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.HarcourtBooks.com

First Harcourt paperback edition 2008

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Smith, Roland, 1951–

Peak/Roland Smith.

p. cm.

Summary: A fourteen-year-old boy attempts to be the youngest person to reach

the top of Mount Everest.

[1. Mountaineering—Fiction. 2. Everest, Mount (China and Nepal)—Fiction.

3. Survival—Fiction. 4. Coming of age—Fiction.] I.Title.

PZ7.S65766Pe 2007

[Fic]—dc22 2006024325

ISBN 978-0-15-202417-8

ISBN 978-0-15-206268-2 pb

Text set in Plantin

Designed by April Ward

H G F E D C B A

Printed in the United States of America

This is a work of fiction. All the names, characters, organizations, and events portrayed

in this book are products of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to any

organization, event, or actual person, living or dead, is unintentional.

This book is for Marie, for giving me all the things that matter

MOLES KINE #1

THE ASSIGNMENT

MY NAME IS PEAK. Yeah, I know: weird name. But you don't get to pick your name or your parents. (Or a lot of other things in life for that matter.) It could have been worse. My parents could have named me Glacier, or Abyss, or Crampon. I'm not kidding. Accordin to my mom all those names were on the list.

Vincent, my literary mentor (at your school this would be your English teacher), asked me to write this for my year-end assignment (no grades at our school).

When Vincent reads the sentence you just read he'll say: Peak, that is a run-on sentence and chaotically parenthetical. (That's how he talks.) Meaning it's a little confusing and choppy. And I'll tell him that my life is (parenthetical) and the chaos is due to the fact that I'm starting this assignment in the back of a Toyota pickup in Tibet (aka China) with an automatic pencil that doesn't have an eraser and it's not likely that I'm going to find an eraser around here.

Vincent has also said that a good writer should draw the reader in by starting in the middle of the story with a hook, then go back and fill in what happened before the hook.

Once you have the reader hooked you can write whatever you want as you slowly reel them in.

I guess Vincent thinks readers are fish. If that's the case, most of Vincent's fish have gotten away. He's written something like twenty literary novels, all of which are out of print. If he knew what he was talking about why do I have to search the dark, moldering aisles of used-book stores to find his books?

(Now I've done it. But remember this, Vincent: Writers should tell the brutal truth in their own voice and not let individuals, society, or consequences dictate their words! And you thought no one was listening to you in class. You also know that I really like your books, or I wouldn't waste my time trying to find them. Nor would I be trying to get this story down in the back of a truck in Tibet.)

Speaking of which...

This morning we slowed down to get around a boulder the size of a school bus that had fallen in the middle of the road. In the U.S.A. we would use dynamite or heavy equipment to move it. In Tibet they use picks, sledgehammers, and prisoners in tattered, quilted coats to chip the boulder down to nothing. The prisoners smiled at us as we tried not to run over their shackled feet on the narrow road. Their cheerful faces were covered in nicks and cuts from rock shrapnel. Those not chipping used crude wooden wheelbarrows to move the man-made gravel over to potholes, where very old Tibetan prisoners used battered shovels and rakes to fill in the holes. Chinese soldiers in green uniforms and with rifles slung over their shoulders stood around fifty-gallon burn barrels smoking cigarettes. The prisoners looked happier than the soldiers did.

I wondered if the boulder would be gone by the time I came back through. I wondered if I'd ever come back through.

THE HOOK

I WAS ONLY TWO-THIRDS up the wall when the sleet started to freeze onto the black terra-cotta.

My fingers were numb. My nose was running. I didn't have a free hand to wipe my nose, or enough rope to rappel about five hundred feet to the ground. I had planned everything out so carefully, except for the weather, and now it was uh-oh time.

A gust of wind tried to peel me off the wall. I dug my fingers into the seam and hugged the terra-cotta until it passed.

I should have waited until June to make the ascent, but no, moron has to go up in March. Why? Because everything was ready and I have a problem with waiting. I had studied the wall, built all my custom protection, and picked the date. I was ready. And if the date passed I might not try it at all. It doesn't take much to talk yourself out of a stunt like this. That's why there are over six billion people sitting safely inside homes and one...

"Moron!" I shouted.

Option #1: Finish the climb. Two hundred sixty-four feet up, or about a hundred precarious fingerholds (providing my fingers didn't break off like icicles).

Option #2: Climb down. A little over five hundred feet, two hundred fifty fingerholds.

Option #3: Wait for rescue. Scratch that option. No one knew I was on the wall. By morning (providing someone actually looked up and saw me) I would be an icy gargoyle. And if I lived my mom would drop me off the wall herself.

Up it is, then.

I timed my moves between vicious blasts of wind, which were becoming more frequent the higher I climbed. The sleet turned to hail, pelting me like a swarm of frozen hornets. But the worst happened about thirty feet from the top, fifteen measly fingerholds away.

I had stopped to give the lactic acid searing my shoulders and arms a chance to simmer down. I was mouth breathing ( partly from exertion, partly from terror), and I told myself I would make the final push as soo

n as I caught my breath.

While I waited, a thick mist drifted in around me. The top of the wall disappeared, which was just as well. When you're tired and scared, thirty feet looks about the length of two football fields, and that can be pretty demoralizing. Scaling a wall happens one foothold and one handhold at a time. Thinking beyond that can weaken your resolve, and it's your will that gets you to the top as much as your muscles and climbing skills.

Finally, I started breathing through my runny nose again. Kind of snorting, really, but I was able to close my mouth every other breath.

This is it, I told myself. Fifteen more handholds and I've topped it.

I reached up for the next seam and encountered a little snag. Well, a big snag really...

My right ear and cheek were frozen to the wall.

To reach the top you must have resolve, muscles, skill, and...

A FACE!

Mine was anchored to that wall like a bolt, and a portion of it stayed there when I gathered enough resolve to tear it loose. Now I was mad, which was exactly what I needed to finish the climb.

Cursing with every vertical lunge, I stopped about four feet below the edge, tempted to tag this monster with the blood running down my neck. But instead I took the mountain stencil out of my pack (cheating, I know, but you have to have two free hands to do it freehand), slapped it on the wall, and filled it in with blue spray paint.

This is when the helicopter came up behind me and nearly blew me off the wall.

"You are under arrest!" an amplified voice shouted above the deafening rotors.

I looked down. Most of the mist had been swirled away by the chopper rotors, and for the first time in an hour I could see the busy street eight hundred feet below the skyscraper.

A black rope dropped down next to me, and two alarmed and angry faces leaned over the edge of the roof.

"Take the rope!"

I wasn't about to take the rope four feet away from my goal. I started up.

"Take the rope!"

When my head reached the top of the railing they hauled me up and cuffed my wrists behind my back. They were wearing SWAT gear and NYPD baseball caps, and there were a lot of them.

One of the cops leaned close to my bloody ear. "What were you thinking?" he said, then jerked me to my feet and handed me off to a regular street cop.

"Get this moron to emergency."

A COUPLE OF STITCHES & THE SLAMMER

WHEN I STEPPED OUT of the elevator into the lobby I was shocked by the swarm of reporters with flashing cameras. How did they get there so quickly?

"He's just a kid."

"What's your name?"

"He's bleeding."

"Why'd you do it?"

"Did you make it to the top?"

I didn't answer any of their questions. In fact, I barely looked at them. The whole point of a spectacular tag is not the artwork; it's the mystery of how it was done.

A subway rider goes by the same seventeen abandoned freight cars parked on a sidetrack, week after week, year after year, then one morning all seventeen of them have been tagged top to bottom with wild beautiful graffiti. Or a driver in bumper-to-bumper traffic drives under the same overpass a thousand times, barely noticing it, until the morning the entire span is painted Day-Glo orange and green.

How'd they do that?

Scaffolds?

In one night?

How many of them were there?

Where were the cops?

What's the point?

The mystery. That's the point. And there isn't enough of it, in my opinion.

My little blue mountains were small, but I made up for their size by putting them in audacious places where they might never be seen except by a bored office worker or window washer. This was my sixth skyscraper. I had planned to do nine all together. Why? I have no idea. Now everyone would know how I did it. The mystery was gone and that was the worst part of getting caught.

Or so I thought.

I expected my mom to show up in the emergency room and tear off my left ear, but she didn't. (And it turned out that my right ear was still attached to my head, as was most of my cheek.)

The East Indian emergency doc took a look at my face under the light for a minute or two, then asked me what happened, eyeing the two cops standing in the doorway as if they were the ones who had messed me up.

"My face froze to a wall."

"You should have used lukewarm water to unfreeze it."

"If I'd had some handy I would have."

"I'm going to clean it up and put in a couple of little stitches."

I was out of there in less than an hour. The two cops drove me to the police station and put me in a filthy room with a two-way mirror. I didn't look so hot. I didn't feel so good, either. My head throbbed. My arms and legs ached. And I had four fingernails split all the way down the middle. It felt like someone had lit them on fire. The emergency doc hadn't even bothered to look at them.

After what seemed like two days the door opened and a tired-looking detective in a rumpled suit came in carrying my backpack and a thick file. He dumped the contents of the pack on the table and went through everything piece by piece. When he finished he scooped the stuff back in, then looked at me and shook his head.

"You messed up, Pete."

"Peak," I said.

"Like in 'mountain peak'?"

"Right."

"Weird name."

"Weird parents."

"Yeah, I just talked with your mother. She said that I had her permission to beat you to death."

Good old Mom.

"I got another phone call," he added. "The mayor. I've been a cop for thirty-five years, and I've never gotten a personal call from the mayor. He's upset. Turns out he was at a reception in the Woolworth Building. They thought you were a terrorist, but it's pretty clear now that you're just a moron."

He stared at me, waiting for a reaction. I didn't give him one. I was a moron. I should have checked the building's evening schedule more carefully before I scaled it. The reporters hadn't rushed over to snap photos of me. They were already there for the mayor's reception, and so were the cops.

"They'll take you over to JDC in a bit."

"What's JDC?" I hadn't been arrested before.

"Juvenile Detention Center. You'll stay there until you're arraigned."

I wasn't sure what that meant, either, and the detective must have sensed this because he explained that there was a separate court system for juvenile defendants. The district attorney would decide what the charges would be and I would have to go before a judge and plead guilty or not guilty.

"Then they'll let me out," I said.

"Maybe, maybe not. Depends on how much the bail is and whether your parents can cough up the dough. Or, they might deny bail all together, which means you'll be in JDC until your trial or sentencing date. That could be months. The courts are backed up."

My mouth went dry.

"I haven't been in trouble before," I said.

"You mean you haven't been caught before." The detective opened the file folder and spread out three photographs on the table. "We've been tracking these tags for quite a while now. Looks like we caught the tagger red-handed."

The photos were grainy, obviously taken with a long telephoto lens, but the blue stenciled mountains were clear enough.

Two uniformed cops were waiting for me outside the interrogation room along with my mom, who was so mad she could barely speak. She looked at the bandages on my face and managed to ask if I was okay.

"Yeah, I'm fine."

"We've got to take him to JDC, ma'am," one of the cops said.

Mom nodded, then looked at me. "We'll see what we can do, Peak. But you've really done it this time."

The cops led me away.

BY THE THIRD DAY at JDC I was climbing the wall (literally) until my counselor (that's what they call the guards here) told me to stop.

Spider Boy, Fly Boy, The Gecko Kid was front-page news every morning. Ea

ch article dug deeper and deeper into my family's past: my mom, dad, stepfather, even my twin sisters were targets. There were infrared photos of me clinging to the scraper, photos from school, photos of my mom and dad when they were rock rats. And my other two blue mountain tags had been discovered.

I stopped reading the newspaper accounts after the second day and left the common room when the news came on the television.

They limited our phone calls at JDC. I was only able to catch Mom once to ask her what was going on, but she was meeting with the attorneys and didn't have time to talk.

On the morning of the fourth day my counselor came into my room (that's what they call the cells) and said I had a visitor. Finally!

I was pretty disappointed to see it was Vincent in the visiting room instead of my mom. (No offense, Vincent.) He looked a little shocked when he saw my scabbed-over face and ear.

"I brought some books for you to read," he said, pushing a couple of paperbacks across the table. "I imagine it gets a bit boring in here."

"Yeah. Thanks."

"I also brought along a couple Moleskine notebooks." He took two black, shrink-wrapped notebooks out of his bag and set them on the table like they were sacred texts. "They are made in Italy. Van Gogh, Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, Bruce Chatwin drew or wrote in Moleskines."

"Really?"

I guess I'd better tell you a little more about my school. It's a special school. In fact, so special that it doesn't have an official name. It's simply known as the Greene Street School, or GSS, because that's the street it's on. There are one hundred students, kindergarten through high school, from all over Manhattan. Most of the kids are prodigies—meaning they play music, sing, dance, act, solve math problems computers can't solve—and me ... who can't do any of these things. I got in because of my stepfather, Rolf Young. He's on their advisory board and does all of their legal work pro bono, meaning for free. The school is two blocks from our loft, and my twin sisters go there, too, but unlike me, they deserve to be there. They are both piano wizards.

It took them a year to figure out my talent, which I think they made up so Rolf would continue to do stuff for free.